A fundamental principle of scientific enquiry was stated most famously by Carl Sagan:

“Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” And no, he wasn’t talking about the O.J. Simpson trial.

In writing pieces about dead folks, based largely upon material from third- and fourth-party sources, I am constantly aware of the possibility of being horribly, horribly wrong. I liken it to what is generally called “the fossil record”: as an aspiring paleontologist at age 6, I learned one set of suppositions and conclusions about the prehistoric world, based upon what had been dug up, up to that point in time. Half a century later, we’ve dug up creatures and evidence that have caused most of our understanding of prehistory to be discarded, and then rebuilt…likely to be discarded again.

Oh, well—so it goes. No one ever said history was a business for cowards.

My point is that I want to get things right, and that’s particularly difficult when little information is available. Which brings me back to my subject, Stan White. My interest was piqued by tiny ads in Audio magazine for Stan’s “Shot Glass” speakers, 40 years ago. I subsequently discovered that Stan had a long history in hi-fi, and as it turned out, he was active in it for several decades after those ads ran.

Since last issue, I’ve learned a great deal more about Stan and his work. Part came from plain old research, including bleary-eyed reading of Stan’s numerous patents; much more came from Stan’s longtime friend and agent in Germany, Hermann Ruwwe (Vielen Dank, Hermann!). Let’s backtrack a little, filled in with additional info:

Stanley Fay White was born in Minnesota, ca. 1920, grew up in St. Paul. After serving as a meteorologist in the Air Force during World War II, he studied physics at Rensselaer Polytechnic in New York state, with additional studies at the University of Chicago. After the war he devoted himself to the design of electronics and speakers designed to faithfully reproduce music.

Why?

In a 1975 interview with High Fidelity Trade News (and who knew that such a mag ever existed?), White said that the invention and use of the atomic bomb greatly influenced his worldview: “When I saw how the work of physicists was being harnessed by the military, I decided to apply my mind to creating alternative and peaceful ways of getting energy from the atom.”

The products that appeared beginning in the early ‘50’s, gave evidence of an active and wide-ranging intellect, unafraid to explore new ground …occasionally coupled with the over-the-top exuberance (a far nicer word than hype)often seen in that era (think tailfins, push-up bras, Technicolor, 3-D). There also seemed to be a bit of an obsession with celebrities, from music and the movies.

White’s US patent # 2,866,513, filed November 24, 1952, simply headed “Apparatus for Generating Sound”, details the design and construction of variable-flare horns for loudspeakers, primarily back-loaded horns which could be curled within a cabinet behind a driver. This was “the Miracle of Multi-Flare!”, as White’s gosh-wow ads of the period put it.

Even within the hoopla there was evidence of a real physical and philosophical basis. Under the heading, “Breaking the audio sound barrier through the Miracle of Multi-Flare!”, the text read: “A New Conception of High Fidelity…Sound is a three dimensional audio vibration occurring along a time axis (a fourth dimension ). Through THE MIRACLE OF MULTI-FLARE [he just couldn’t help himself] , you can hear…for the first time…sounds reproduced as they originally occurred in their proper time sequence.”

Keep in mind that this is 20 years before time-alignment of loudspeaker drivers and linear phase response were thought to be important—much less, mentioned in a mainstream ad. Stan White brand speakers so equipped were listed between $69.50-$1500—certainly not inexpensive in the early to mid-‘50’s, and equivalent to $625-$13,500 today.

Years later, White was still proud of his accomplishments during this period, although there were hints of both hyperbole and resignation in this email written to me in 2003: “I described room capacitance as a factor in a patent filed in 1952 [mentioned above—Ed.]. This is why my tiny Le Petite could generate 20 Hz in a corner of a reasonable sized room. Sound obeys its own laws, not the laws some say it should have. Ignorance can be a terrible thing to deal with. Creativity is not a blessing—it is a curse.”

Room-loading by loudspeakers is a topic generally thought of in conjunction with Paul Klipsch or Roy Allison—but White was clearly aware of the phenomenon, and utilized it in his mono loudspeaker designs.

The November, 1953 issue of Audio featured an article by White describing his Powrtron (sic) amplifier. A vacuum tube amp (of course), Powrtron was notable in that it featured a version of the Van Scoyoc phase inverter, was designed to have linear power response invariant of load, and included a plug-in electronic crossover that could be used with two amp sections on the same chassis. Again, this was forward-thinking stuff for the times: Marantz’s Model 3 electronic crossover didn’t appear until 1957.

The Powrtron was offered as a commercial product in 10- and 20-watt versions, without or with the crossover, respectively. The Audio article can be read here: http://www.audiofaidate.org/it/articoli/Powtron.pdf

White had two notable associations within the world of music-recording: with Duke Ellington, and with Bill Putnam. Ellington requires no introduction, and owned electronics and speakers from White. A 1954 ad shows Ellington and White at the Chicago Audio Fair under the heading, “Why I bought a Stan White Speaker”. The hipsterish text reads, “Stan White Speakers are the most! We use them exclusively in all our reproduction work.” Putnam opened Universal Recording in Chicago after the war, and it was an early independent (non-label-affiliated) recording studio, on the leading edge of technological advances: Putnam and Les Paul are jointly credited with having invented multitrack recording. White amps in speakers were in use at Universal when Ellington and his band recorded half of the Ellington ’55 album there. (Putnam later moved to LA and founded United Recording, backed by Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby. He also founded the equipment brands Universal Audio and UREI).

If you are a reader of fine print, you may have noticed “A Division of Eddie Bracken Enterprises” at the bottom of the above ad. White’s interest in Hollywood was nearly his undoing: introduced to Eddie Bracken (a vaudevillian turned comic film actor best known for roles in several Preston Sturges films, Bracken went on to have a lengthy Broadway career— I even saw him in Hello, Dolly in 1978, while on my honeymoon), White found a hi-fi fan whom he felt could both bankroll him and introduce him to Hollywood stars and give his business a boost.

Stan ruefully recalled the association in a staccato 2003 email: “No one ever made money with Bracken. He put $5000 in, and then shortly afterwards wrote a check for cash (the $5000), and blew it at the track. He ‘loaned’ his daughter’s inlaws $100,000 and then went bankrupt for $6,000,000, almost destroying the inlaws’ business…Over his career he conned over $25,000,000 from friends and acquaintances. Had five kids. Wife lived like a church mouse most of her life. Generosity was not a word in his vocabulary. Psychotic as hell.”

They always say that a bad business-partner is worse than a bad spouse, but the Bracken association did at least result in a bizarre ad featuring Charlton Heston and his wife stiltedly endorsing Stan White speakers. Whether that was a blessing or a curse, who knows?

The May, 1956 issue of Audio featured another article by White, describing “Beta-Tron”, a system utilizing motional feedback from a second coil on the tweeter to the amp to reduce distortion, again using the Powrtron amp with its electronic crossover. The system was offered as a commercial system, but apparently didn’t achieve success. The next commercial system I’m aware of that featured such a second coil/feedback set-up was the Infinity Servo-Statik of 1968, followed by more mainstream applications from Philips in the 1970’s. White’s system was unusual in that it was utilized on the tweeter, where the others used it on the woofer, for lower IM and Doppler distortion. Why White used it on the tweeter is a bit of a mystery (“that doesn’t make any sense to me at all,” said Infinity founder and Servo-Statik designer Arnie Nudell, when I described White’s servo-tweeter to him). The article can be read here (scroll down to page 28).

During 1956-‘57, White received a pair of patents (#2,923,783, “Electro-Acoustical Transducer”and #3,046,362, “Speaker”)pertaining to the construction and configuration of speaker drivers. One describes layered cone-construction using multiple materials up to ½” in thickness, the goal being the creation of a driver which would truly behave as a piston. The other describes drivers driven by voice coils at their periphery—the goal of which was unclear. White did build a speaker with a thick-coned 15” woofer with its voice coil at the outer edge, but it’s unclear if it ever reached production. For that matter, exactly what “production” meant for the Stan White brand is unclear.

All told, White received seven patents in the US and one in Germany, all pertaining to loudspeaker design and/or construction, and they contain a number of unique ideas and features. They also tended to break new ground; his patents are referenced in patents held by AKG, B&W, Bose, Fostex, Goodmans, Harman, JBL, JL Audio, Paradigm, Pioneer, Polk, and Sony. Pretty impressive for a little guy, working alone.

After the late ‘50’s, there a number of lost years in the life and career of Stan White—at least, as far as me being able to detail his activities. White’s associate Hermann Ruwwe mentions simply, “Stan worked for Rectilinear, Avid, GE, and a number of other companies,” so presumably there was consulting work or stints as an employee.

As mentioned ‘way back at our beginning, I first encountered Stan White by way of tiny classified ads for his “Shot Glass” speakers in Audio magazine around 1975. It appears to have been a period of renewed creativity, as two more patents were granted in 1976 (#3,961,378, “Cone Construction for Loudspeaker”, and #3,997,023, “Loudspeaker with Improved Surround”)which detailed the salient features of his “glasscone” drivers.

To clarify: the cones were not like Mom’s Pyrex baking dish; they were composed of plastics reinforced by glass fibres or micro-spheres. The patents very precisely define the construction and geometry of the ribbed, mostly-flat cone and the parabolic surround.

White continued to refine the drivers and his “Shot Glass” systems for the rest of his life, as well as developing some unique theories on the nature of matter, from the particle level to the cosmic. In the US speakers and the occasional Powrtron-based amp were sold under the White Sound brand; limited numbers of glasscone-based speakers are still made today in Germany by Ruwwe Audio.

As in the ‘50’s, White’s product blurbs were a combination of the factual and the audacious. A late-‘70’s brochure for the Shot Glass speakers says that “…our cone moves like a chunk, rather than flapping like a bed sheet…” and that the center cap “ …like the keystone of an arch cements the cone structure into a granitelike mass that is indestructible….”

Echoing his earlier statements about bass from small speakers, White wrote about his ‘70’s experiences at Chicago CES: “Four of my Shot Glass speakers in a 20 ft. square alignment put out 20 Hz. in McCormick Place. People thought I was Cerwin-Vega! [ the providers of speakers for the Sensurround theater systems of the ‘70’s]”

In the 1975 High Fidelity Trade News article, White discussed theories about atomic structure and a process by which synthetic diamonds could be made “big enough to make telescope lenses”. Even in emails to me in the early 2000’s, Stan mentioned “his process”, never making it clear if it had ever been put to practice. Regarding diamond circuit chips he wrote, “In my process, diamond is laid down in layers with circuits on them. The wafer can be a half inch square, vertically connected. The shortened distance increases speed.

“Silicon circuits are made by diffusion,” he wrote. “This means that if the chip gets hot, the diffusion continues and the circuits short. My diamond units are deposited: no diffusion, life very long. Diamond never melts—at 4000 degrees it turns to gas…a small unit will handle gobs of power. I like them.”

The communications I received from the then-octogenarian Stan White were an often-puzzling mix of insights and anxiety, riddled with sad tales of abuse and lost opportunities. As with “his process” of diamond production, I couldn’t always tell what was theory, and what had actually occurred. He produced a book on “new physics” which I found interesting but largely incomprehensible; I wasn’t knowledgeable enough to judge the work. I’m still not. He was clearly a very bright guy with some interesting ideas who had a number of accomplishments, as well as a number of disappointments.

Hermann Ruwwe wrote to me, “Stan passed away Dec. 14, 2006, he died peacefully in his sleep. He was one of a kind, old school, no gimmicks, an American hero in the audio field.”

I’m sorry Stan wasn’t better known in his homeland. A visionary and a dreamer, he clearly had a lot to offer.

One of the Burwell speakers, in all its woody glory.

One of the Burwell speakers, in all its woody glory. A bunch of old Altec horns and brand new solid wood ones.

A bunch of old Altec horns and brand new solid wood ones. Vintage JBL and Altec drivers.

Vintage JBL and Altec drivers. A pair of very early Altec-Lansing 515 woofers.

A pair of very early Altec-Lansing 515 woofers. Overhead view of the Burwells' beautiful solid wood midrange horn.

Overhead view of the Burwells' beautiful solid wood midrange horn. Cookie's mixing console at Blue Coast

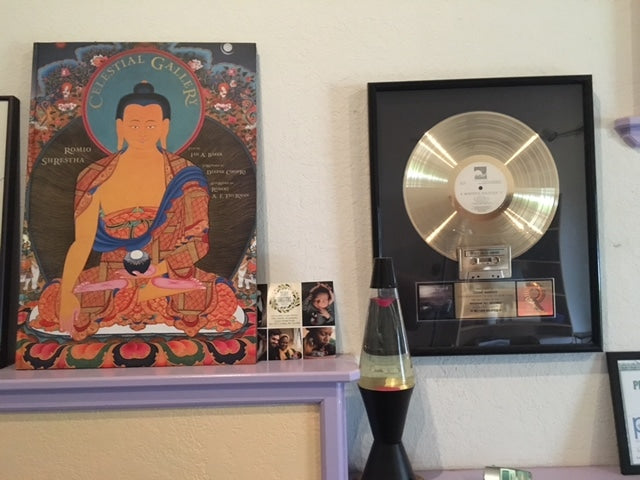

Cookie's mixing console at Blue Coast Buddha, Lava Lamp, and a gold record--the perfect studio feng shui!

Buddha, Lava Lamp, and a gold record--the perfect studio feng shui! Cookie Marenco

Cookie Marenco Neil Young's old ranch is waaaaay down that road.

Neil Young's old ranch is waaaaay down that road. Type 57 Bugatti. We're not worthy.

Type 57 Bugatti. We're not worthy. Grosser Mercedes, like Der Fuehrer used to love.

Grosser Mercedes, like Der Fuehrer used to love. A swoopy, Pebble Beach-winning 1938 Talbot-Lago T150-C.

A swoopy, Pebble Beach-winning 1938 Talbot-Lago T150-C. I wasted a lot of hours on one of these, back in high school....

I wasted a lot of hours on one of these, back in high school....