More crate digs, and leading off with a couple of notable comedy albums. Yeah, I know, it’s not music, but still listenable, enjoyable, and very collectible. And some of it, like the Monty Python or Cramps, isn’t available on most streaming services.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Monty Python’s Flying Circus -

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Monty Python’s very first release, featuring the original broadcast versions of some of their silliest and most memorable sketches. Once upon a time, I had the Pye label LP for this title, but that was waaaaaay back when. At some point during the move to Atlanta in the early Eighties, a box of LPs disappeared, with this one among the lost. I was under the impression this material had never been released on CD, and while I’d occasionally seen a few really beaten and worn vinyl copies, nothing in terms of a digital format release ever showed up anywhere.

I found this at a local Goodwill last fall; it was bearing the correct half-price sticker color, and shockingly, still in the original shrink wrap. I just about keeled over on the spot. And in the time it took to get to my car and pop it into the CD player, the out-of-control, mindless juvenile part of my soul that lurks just below the surface had gone into full-on, totally LMAO mode. I couldn’t believe how such skits as “Flying Sheep,” “Crunchy Frog,” “Nudge Nudge Wink Wink,” “The Lumberjack Song,” “Albatross,” and the “Dead Parrot Sketch” still had me rolling in uproarious laughter, just about winkling my shorts in the process. The execution by the Pythons in these classic bits is still remarkably effective, even without the visual element.

As I said earlier, I was under the impression that this classic collection had never been released as a CD; that assessment is, in fact, completely correct. The “CD” I found is actually an “audio book”; come to find out, that’s how it’s been marketed all these years. There was the LP and the cassette, but at the point when it was finally released on CD (1985), for some reason, they decided to sell it as an audio book rather than as a catalog CD title! Hence the reason there was never any reference to it when I’d occasionally take a stab and try and order it from a record store. I should have tried a book store instead!

Anyway, if you’re a huge fan, this outstanding collection is indispensable, and can apparently still be ordered (through the proper channels, of course) online. It’s a worthwhile addition to your music server, and fills a huge void in the early Python catalog. And the sound quality is miles beyond my recollection of my old Pye LP pressing. Unfortunately, you won’t find it on any streaming services other than Amazon. Still, should you stumble across it, this collection is highly recommended!

BBC/Pye Records, CD (download/streaming from Amazon)

Firesign Theater

Firesign Theater -

Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers

An absolute classic of surreal, stream of consciousness American humor, 1970’s

Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers was the Firesign Theater’s first album that maintained continuity in the story line across both sides of the LP. And, surprisingly, flowed thematically in succession from the closing of Side Two of the previous album,

How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All, and into the opening Side One of their next album,

I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus. I still have pretty pristine vinyl for

Don’t Crush That Dwarf, but the object of most of my recent searches has been to add more files to the digital music server—so I was really stoked when this CD turned up at a booth in an antique mall. Yeah, CDs are so old now, they’re considered antiques!

The album basically chronicles the antics of one George Tirebiter, a ne’er-do-well, juvenile delinquent turned war hero and actor; his heroics weave in and out of a complex maze of storylines. Where it can be really difficult to determine when the story is actually here-and-now, or part of a really convoluted movie plotline that’s seemingly continually playing in various stages throughout the production. And, of course, there are plenty of the always-entertaining and off-kilter Firesign ads and commercials, along with religious and televangelist segments galore. There are copious helpings of plotlines drenched in totally crazed satire, and the dialogue is often about as juvenile, trashy, and quite literally “out there” as it gets! I was a teenager when I first heard this at my brother’s house over his Koss Pro 4A headphones (didn’t want my mom to hear the kind of trash I was listening to!). Regardless, my brother’s overprotective (soon to be ex) wife was convinced that I was going straight to Hell for listening to such garbage!

I was aware of a very hard to find MFSL CD release of this title in 1987, but had no idea that Columbia/Sony/Legacy had also released a CD version in 2001—this one! The sound quality is really superb, and it’s a real joy to listen to the bizzaro/alternate reality the Firesigns created—now with the ease of digital technology. And it shows up on most of the major streaming services, so if you’re not familiar, have a listen. You won’t regret it, it comes highly recommended!

Columbia/Sony/Legacy, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music)

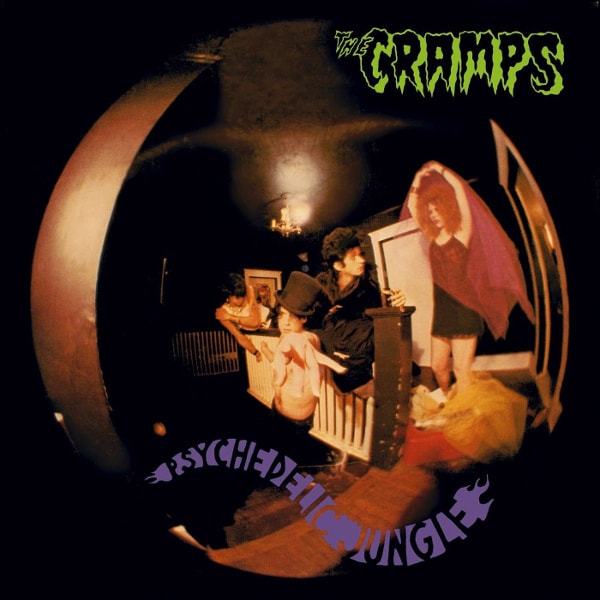

The Cramps

The Cramps -

Psychedelic Jungle

The Cramps are one of the most storied bands of the Eighties; their raucous, distinctive brand of rockabilly was eventually given the moniker “Shockabilly” because they didn’t easily fit into any of the typical categories. 1981’s

Psychedelic Jungle is technically their second album, following the EP

Gravest Hits and their first full-length album,

Songs the Lord Taught Us. However—and despite how entertaining the first two releases were—

Psychedelic Jungle is definitely their first fully-formed and most accomplished album up to that point. And the over-the-top, on-stage vocal antics of lead singer Lux Interior are well documented on the album, along with incredible lead guitar work from Poison Ivy. Kid Congo Powers stepped in as the second guitarist on this release; his work is exceptionally effective. And drummer Nick Knox pounds out the heavy beats here; his drumming is one of the undeniable highlights on every Cramps release. Shockingly, The Cramps didn’t employ a bass player on any of their records or in their live sets until the mid-Eighties, but you don’t really notice the bass’s absence on the tracks here.

As far as I can tell, this album was never released on anything other than on LP in the Eighties; this 1998 CD release, which I scored at a CD Warehouse nearby, is on the original I.R.S. label. Albeit from a European (UK) distributor, and it doesn’t appear to be available on the major streaming services, which seem to have lots of other, later Cramps albums available. Priced at $9, this is one of those unusual discs that I didn’t hesitate to grab—because I’d never seen it anywhere, at any price. Generally, the only Cramps CD you ever see in any shop is the 1984 compilation

Bad Music For Bad People. Which isn’t a bad listen, but sometimes you want to hear the original album, right?

This is also the first album where Lux and Ivy did a major share of the songwriting chores, although some of the most entertaining ones are the remakes of obscure oldies. Like bruising versions of “Green Fuz,” “Goo Goo Muck,” “ Primitive,” and an especially rousing version of Bobby Nolan’s “The Crusher.” The Lux/Ivy penned tunes like “Voodoo Idol,” “Don’t Eat Stuff Off the Sidewalk,” “Can’t Find My Mind,” and “The Natives Are Restless” don’t lag far behind in terms of entertainment value. The performances are incendiary to say the least!

This disc is hard to find, but well worth the price. And with the virtual invisibility of the title for online streaming—no Tidal or Qobuz—worth grabbing if you stumble across one or see a copy online. Highly recommended!

I.R.S. (UK), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Neil Young

Neil Young -

Trans

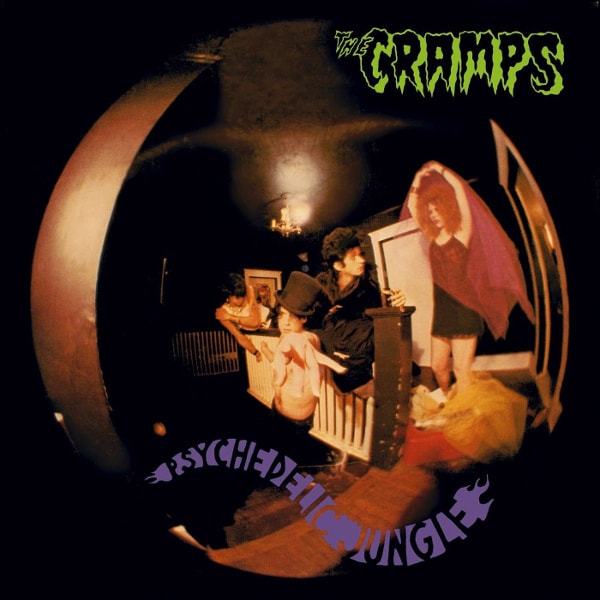

Things were really beginning to gel with my soon-to-be wife and I in 1982. Both of us were huge Neil Young fans, her especially—she was a student at Kent State University when the shootings happened, and the Neil Young-penned “Ohio” really struck a chord with her on a personal level. We’d never seen Neil live, and when I found out he was touring solo in support of the new album

Trans, I got tickets for a show at the University of Georgia coliseum. I already had the album, which was unlike anything that Neil had ever done before—he was just beginning his phase of concept-related albums that spanned the Eighties into the Nineties and forward. Anyway, the concert was fabulous, and Neil performed

Trans virtually in its entirety with minimal accompaniment. And when he performed “Ohio” accompanied only by his acoustic guitar, it was probably the most spine-chilling moment I’ve ever experienced at a live show.

Although

Trans came out at the dawn of the CD era, it was never released as a domestic CD. I had the album at one point, but had basically pretty much forgotten about it until I stumbled across this German Geffen Records import CD at an antique mall—for $2! It starts out with a kind of rockabilly number “Little Thing Called Love,” which was probably more in line with the upcoming album, the retro

Everybody’s Rockin’. From that point, all bets are off, with computer and synthesizer enhanced numbers like “Computer Age,” “We R In Control,” “Transformer Man,” and “Sample and Hold.” And more straightforward rockers like the remake of “Mr. Soul” and the sprawling “Like an Inca.”

This is one of those titles that I was happy to get a few years back, and a great addition to my music server and Neil Young collection. Because it was virtually impossible to find anywhere other than on an LP—try finding a decent, clean pressing with a pristine outer jacket. Nowadays, it’s available on all the major streaming services, so no need for the search, unless you just really desire having a copy. But if you stumble across one at a reasonable price, I’d definitely recommend grabbing it. And at least take a listen on Tidal or Qobuz, it’s a real blast from the past!

Geffen Records (Germany), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Header image courtesy of Pexels.com/Cottonbro.

John Strohbeen and Evan Cordes of Ohm Acoustics.

John Strohbeen and Evan Cordes of Ohm Acoustics. The humble Cal Audio DX-1 CD player and Outlaw 2160 receiver. No doubt as to what those controls do!

The humble Cal Audio DX-1 CD player and Outlaw 2160 receiver. No doubt as to what those controls do! The standard home stereo wiring used for the system's connections.

The standard home stereo wiring used for the system's connections. The Mini Walsh and the Walsh Tall 2000 speakers.

The Mini Walsh and the Walsh Tall 2000 speakers. The prototype Ohm PA-1.

The prototype Ohm PA-1.

The "snowstorm" on the hottest day of the year.

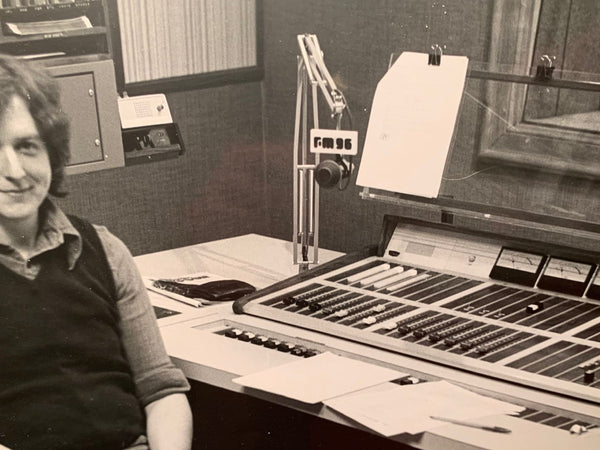

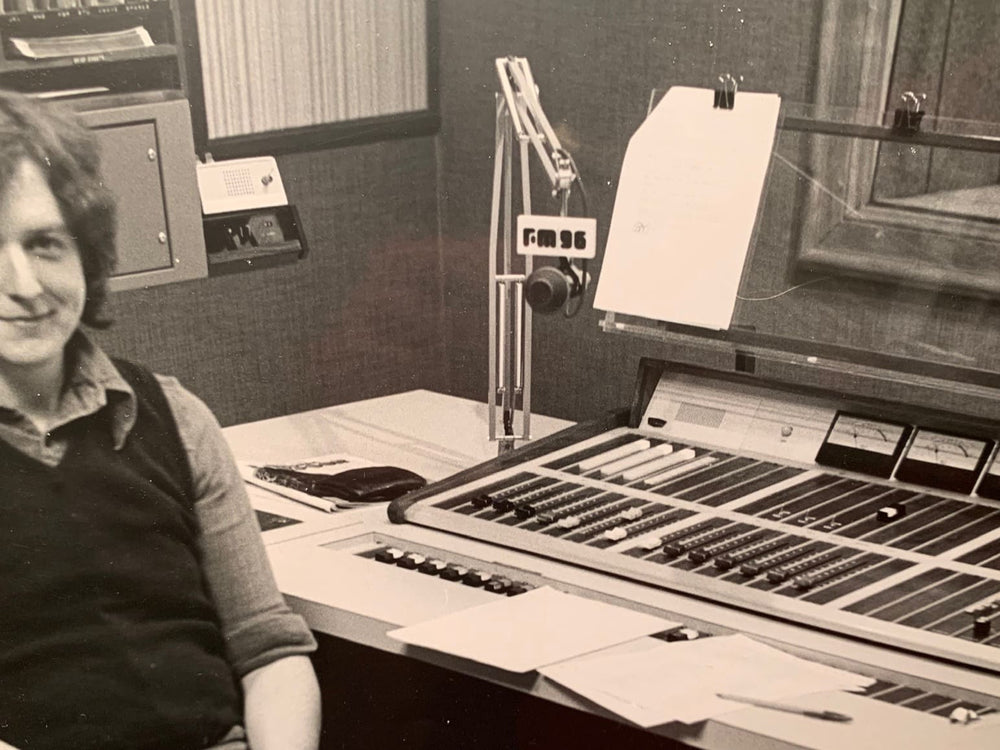

The "snowstorm" on the hottest day of the year. Marty Feldman, Mary Lou Basaraba and Matthew Cope at CJFM.

Marty Feldman, Mary Lou Basaraba and Matthew Cope at CJFM. Donald Sutherland and Matthew Cope at CJFM.

Donald Sutherland and Matthew Cope at CJFM. More snowy hijinks at CJFM.

More snowy hijinks at CJFM.

General Electric VR-II: this is a vintage monophonic moving iron cartridge, featuring two styli, one with a large tip radius for 78 RPM records and one with a small tip radius for 33-1/3 RPM "microgroove" records.

General Electric VR-II: this is a vintage monophonic moving iron cartridge, featuring two styli, one with a large tip radius for 78 RPM records and one with a small tip radius for 33-1/3 RPM "microgroove" records. Van den Hul MC Two moving coil cartridge on an SME tonearm. This cartridge features a line-contact stylus on a boron cantilever.

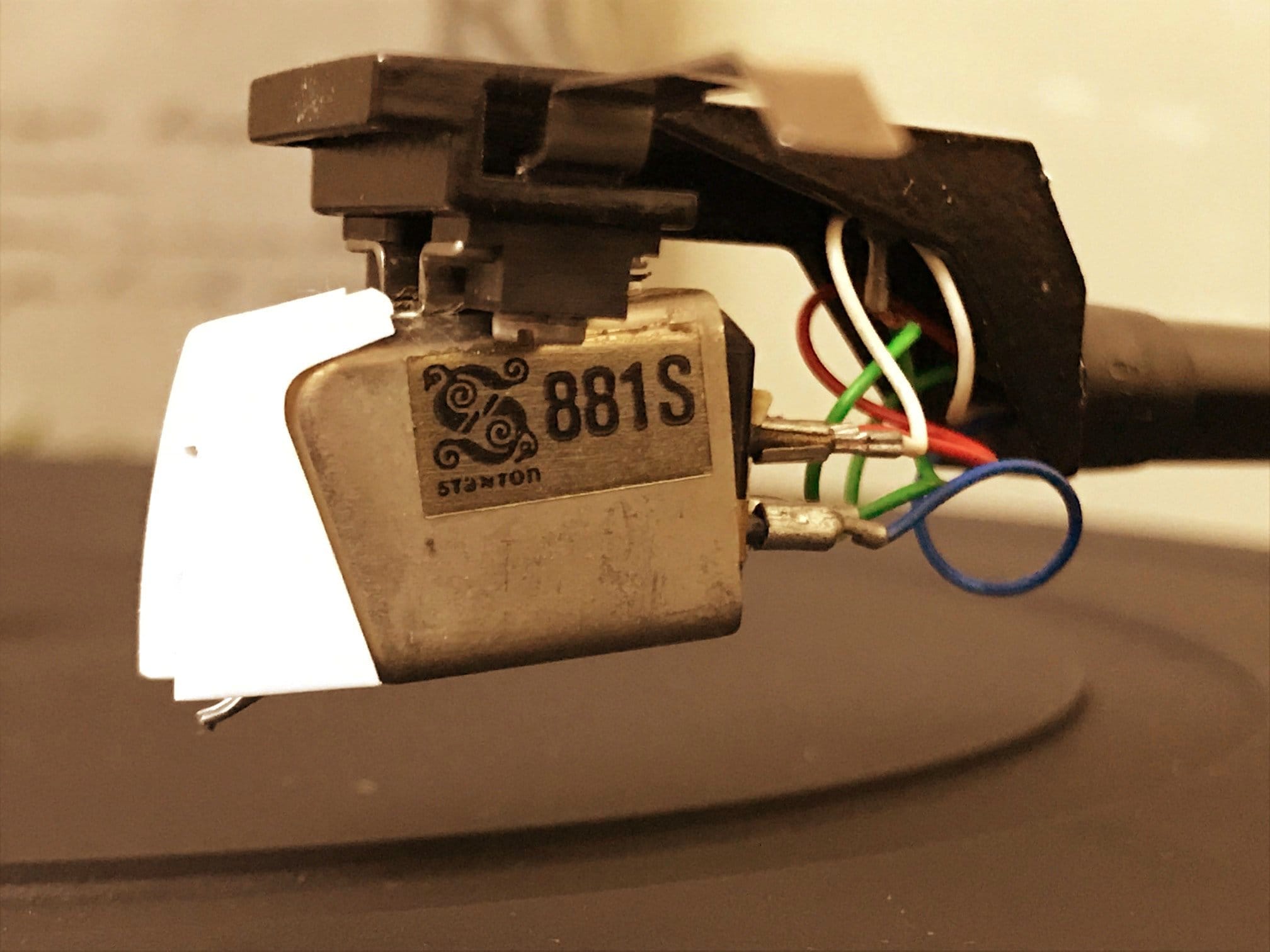

Van den Hul MC Two moving coil cartridge on an SME tonearm. This cartridge features a line-contact stylus on a boron cantilever. Stanton 881S Reference Series moving magnet cartridge with stereohedron stylus.

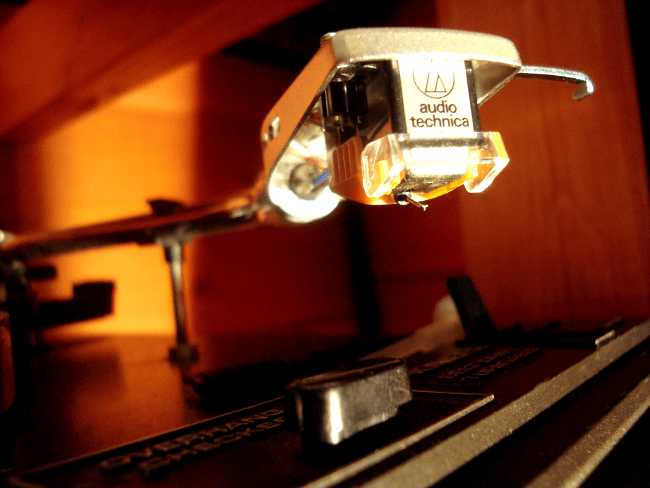

Stanton 881S Reference Series moving magnet cartridge with stereohedron stylus. Audio-Technica AR12XE moving magnet cartridge with line-contact stylus.

Audio-Technica AR12XE moving magnet cartridge with line-contact stylus.

The original Carver Silver Seven monoblock amplifier.

The original Carver Silver Seven monoblock amplifier.

AT&T Labs, Holmdel, NJ.

AT&T Labs, Holmdel, NJ.

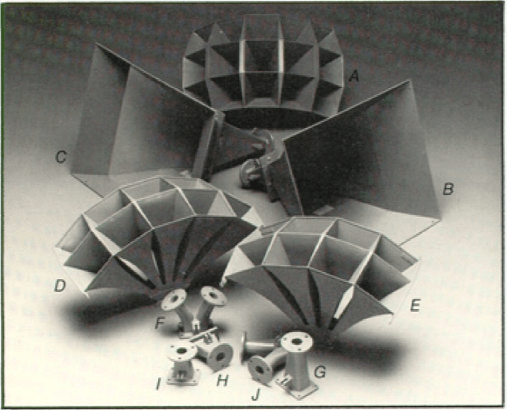

The mighty Altec Lansing Voice of the Theatre A1 speaker system, 1945 catalog. I'll bet he's thinking, "With a little work, it could be adapted for home use..."

The mighty Altec Lansing Voice of the Theatre A1 speaker system, 1945 catalog. I'll bet he's thinking, "With a little work, it could be adapted for home use..." They knew how to make integrated circuits back then! From Machine Design, February 1971.

They knew how to make integrated circuits back then! From Machine Design, February 1971.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus - Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Monty Python’s very first release, featuring the original broadcast versions of some of their silliest and most memorable sketches. Once upon a time, I had the Pye label LP for this title, but that was waaaaaay back when. At some point during the move to Atlanta in the early Eighties, a box of LPs disappeared, with this one among the lost. I was under the impression this material had never been released on CD, and while I’d occasionally seen a few really beaten and worn vinyl copies, nothing in terms of a digital format release ever showed up anywhere.

I found this at a local Goodwill last fall; it was bearing the correct half-price sticker color, and shockingly, still in the original shrink wrap. I just about keeled over on the spot. And in the time it took to get to my car and pop it into the CD player, the out-of-control, mindless juvenile part of my soul that lurks just below the surface had gone into full-on, totally LMAO mode. I couldn’t believe how such skits as “Flying Sheep,” “Crunchy Frog,” “Nudge Nudge Wink Wink,” “The Lumberjack Song,” “Albatross,” and the “Dead Parrot Sketch” still had me rolling in uproarious laughter, just about winkling my shorts in the process. The execution by the Pythons in these classic bits is still remarkably effective, even without the visual element.

As I said earlier, I was under the impression that this classic collection had never been released as a CD; that assessment is, in fact, completely correct. The “CD” I found is actually an “audio book”; come to find out, that’s how it’s been marketed all these years. There was the LP and the cassette, but at the point when it was finally released on CD (1985), for some reason, they decided to sell it as an audio book rather than as a catalog CD title! Hence the reason there was never any reference to it when I’d occasionally take a stab and try and order it from a record store. I should have tried a book store instead!

Anyway, if you’re a huge fan, this outstanding collection is indispensable, and can apparently still be ordered (through the proper channels, of course) online. It’s a worthwhile addition to your music server, and fills a huge void in the early Python catalog. And the sound quality is miles beyond my recollection of my old Pye LP pressing. Unfortunately, you won’t find it on any streaming services other than Amazon. Still, should you stumble across it, this collection is highly recommended!

BBC/Pye Records, CD (download/streaming from Amazon)

Monty Python’s Flying Circus - Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Monty Python’s very first release, featuring the original broadcast versions of some of their silliest and most memorable sketches. Once upon a time, I had the Pye label LP for this title, but that was waaaaaay back when. At some point during the move to Atlanta in the early Eighties, a box of LPs disappeared, with this one among the lost. I was under the impression this material had never been released on CD, and while I’d occasionally seen a few really beaten and worn vinyl copies, nothing in terms of a digital format release ever showed up anywhere.

I found this at a local Goodwill last fall; it was bearing the correct half-price sticker color, and shockingly, still in the original shrink wrap. I just about keeled over on the spot. And in the time it took to get to my car and pop it into the CD player, the out-of-control, mindless juvenile part of my soul that lurks just below the surface had gone into full-on, totally LMAO mode. I couldn’t believe how such skits as “Flying Sheep,” “Crunchy Frog,” “Nudge Nudge Wink Wink,” “The Lumberjack Song,” “Albatross,” and the “Dead Parrot Sketch” still had me rolling in uproarious laughter, just about winkling my shorts in the process. The execution by the Pythons in these classic bits is still remarkably effective, even without the visual element.

As I said earlier, I was under the impression that this classic collection had never been released as a CD; that assessment is, in fact, completely correct. The “CD” I found is actually an “audio book”; come to find out, that’s how it’s been marketed all these years. There was the LP and the cassette, but at the point when it was finally released on CD (1985), for some reason, they decided to sell it as an audio book rather than as a catalog CD title! Hence the reason there was never any reference to it when I’d occasionally take a stab and try and order it from a record store. I should have tried a book store instead!

Anyway, if you’re a huge fan, this outstanding collection is indispensable, and can apparently still be ordered (through the proper channels, of course) online. It’s a worthwhile addition to your music server, and fills a huge void in the early Python catalog. And the sound quality is miles beyond my recollection of my old Pye LP pressing. Unfortunately, you won’t find it on any streaming services other than Amazon. Still, should you stumble across it, this collection is highly recommended!

BBC/Pye Records, CD (download/streaming from Amazon)

Firesign Theater - Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers

An absolute classic of surreal, stream of consciousness American humor, 1970’s Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers was the Firesign Theater’s first album that maintained continuity in the story line across both sides of the LP. And, surprisingly, flowed thematically in succession from the closing of Side Two of the previous album, How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All, and into the opening Side One of their next album, I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus. I still have pretty pristine vinyl for Don’t Crush That Dwarf, but the object of most of my recent searches has been to add more files to the digital music server—so I was really stoked when this CD turned up at a booth in an antique mall. Yeah, CDs are so old now, they’re considered antiques!

The album basically chronicles the antics of one George Tirebiter, a ne’er-do-well, juvenile delinquent turned war hero and actor; his heroics weave in and out of a complex maze of storylines. Where it can be really difficult to determine when the story is actually here-and-now, or part of a really convoluted movie plotline that’s seemingly continually playing in various stages throughout the production. And, of course, there are plenty of the always-entertaining and off-kilter Firesign ads and commercials, along with religious and televangelist segments galore. There are copious helpings of plotlines drenched in totally crazed satire, and the dialogue is often about as juvenile, trashy, and quite literally “out there” as it gets! I was a teenager when I first heard this at my brother’s house over his Koss Pro 4A headphones (didn’t want my mom to hear the kind of trash I was listening to!). Regardless, my brother’s overprotective (soon to be ex) wife was convinced that I was going straight to Hell for listening to such garbage!

I was aware of a very hard to find MFSL CD release of this title in 1987, but had no idea that Columbia/Sony/Legacy had also released a CD version in 2001—this one! The sound quality is really superb, and it’s a real joy to listen to the bizzaro/alternate reality the Firesigns created—now with the ease of digital technology. And it shows up on most of the major streaming services, so if you’re not familiar, have a listen. You won’t regret it, it comes highly recommended!

Columbia/Sony/Legacy, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music)

Firesign Theater - Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers

An absolute classic of surreal, stream of consciousness American humor, 1970’s Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers was the Firesign Theater’s first album that maintained continuity in the story line across both sides of the LP. And, surprisingly, flowed thematically in succession from the closing of Side Two of the previous album, How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All, and into the opening Side One of their next album, I Think We’re All Bozos on This Bus. I still have pretty pristine vinyl for Don’t Crush That Dwarf, but the object of most of my recent searches has been to add more files to the digital music server—so I was really stoked when this CD turned up at a booth in an antique mall. Yeah, CDs are so old now, they’re considered antiques!

The album basically chronicles the antics of one George Tirebiter, a ne’er-do-well, juvenile delinquent turned war hero and actor; his heroics weave in and out of a complex maze of storylines. Where it can be really difficult to determine when the story is actually here-and-now, or part of a really convoluted movie plotline that’s seemingly continually playing in various stages throughout the production. And, of course, there are plenty of the always-entertaining and off-kilter Firesign ads and commercials, along with religious and televangelist segments galore. There are copious helpings of plotlines drenched in totally crazed satire, and the dialogue is often about as juvenile, trashy, and quite literally “out there” as it gets! I was a teenager when I first heard this at my brother’s house over his Koss Pro 4A headphones (didn’t want my mom to hear the kind of trash I was listening to!). Regardless, my brother’s overprotective (soon to be ex) wife was convinced that I was going straight to Hell for listening to such garbage!

I was aware of a very hard to find MFSL CD release of this title in 1987, but had no idea that Columbia/Sony/Legacy had also released a CD version in 2001—this one! The sound quality is really superb, and it’s a real joy to listen to the bizzaro/alternate reality the Firesigns created—now with the ease of digital technology. And it shows up on most of the major streaming services, so if you’re not familiar, have a listen. You won’t regret it, it comes highly recommended!

Columbia/Sony/Legacy, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music)

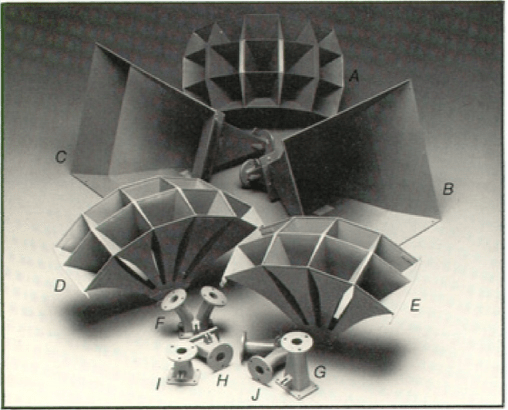

The Cramps - Psychedelic Jungle

The Cramps are one of the most storied bands of the Eighties; their raucous, distinctive brand of rockabilly was eventually given the moniker “Shockabilly” because they didn’t easily fit into any of the typical categories. 1981’s Psychedelic Jungle is technically their second album, following the EP Gravest Hits and their first full-length album, Songs the Lord Taught Us. However—and despite how entertaining the first two releases were—Psychedelic Jungle is definitely their first fully-formed and most accomplished album up to that point. And the over-the-top, on-stage vocal antics of lead singer Lux Interior are well documented on the album, along with incredible lead guitar work from Poison Ivy. Kid Congo Powers stepped in as the second guitarist on this release; his work is exceptionally effective. And drummer Nick Knox pounds out the heavy beats here; his drumming is one of the undeniable highlights on every Cramps release. Shockingly, The Cramps didn’t employ a bass player on any of their records or in their live sets until the mid-Eighties, but you don’t really notice the bass’s absence on the tracks here.

As far as I can tell, this album was never released on anything other than on LP in the Eighties; this 1998 CD release, which I scored at a CD Warehouse nearby, is on the original I.R.S. label. Albeit from a European (UK) distributor, and it doesn’t appear to be available on the major streaming services, which seem to have lots of other, later Cramps albums available. Priced at $9, this is one of those unusual discs that I didn’t hesitate to grab—because I’d never seen it anywhere, at any price. Generally, the only Cramps CD you ever see in any shop is the 1984 compilation Bad Music For Bad People. Which isn’t a bad listen, but sometimes you want to hear the original album, right?

This is also the first album where Lux and Ivy did a major share of the songwriting chores, although some of the most entertaining ones are the remakes of obscure oldies. Like bruising versions of “Green Fuz,” “Goo Goo Muck,” “ Primitive,” and an especially rousing version of Bobby Nolan’s “The Crusher.” The Lux/Ivy penned tunes like “Voodoo Idol,” “Don’t Eat Stuff Off the Sidewalk,” “Can’t Find My Mind,” and “The Natives Are Restless” don’t lag far behind in terms of entertainment value. The performances are incendiary to say the least!

This disc is hard to find, but well worth the price. And with the virtual invisibility of the title for online streaming—no Tidal or Qobuz—worth grabbing if you stumble across one or see a copy online. Highly recommended!

I.R.S. (UK), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

The Cramps - Psychedelic Jungle

The Cramps are one of the most storied bands of the Eighties; their raucous, distinctive brand of rockabilly was eventually given the moniker “Shockabilly” because they didn’t easily fit into any of the typical categories. 1981’s Psychedelic Jungle is technically their second album, following the EP Gravest Hits and their first full-length album, Songs the Lord Taught Us. However—and despite how entertaining the first two releases were—Psychedelic Jungle is definitely their first fully-formed and most accomplished album up to that point. And the over-the-top, on-stage vocal antics of lead singer Lux Interior are well documented on the album, along with incredible lead guitar work from Poison Ivy. Kid Congo Powers stepped in as the second guitarist on this release; his work is exceptionally effective. And drummer Nick Knox pounds out the heavy beats here; his drumming is one of the undeniable highlights on every Cramps release. Shockingly, The Cramps didn’t employ a bass player on any of their records or in their live sets until the mid-Eighties, but you don’t really notice the bass’s absence on the tracks here.

As far as I can tell, this album was never released on anything other than on LP in the Eighties; this 1998 CD release, which I scored at a CD Warehouse nearby, is on the original I.R.S. label. Albeit from a European (UK) distributor, and it doesn’t appear to be available on the major streaming services, which seem to have lots of other, later Cramps albums available. Priced at $9, this is one of those unusual discs that I didn’t hesitate to grab—because I’d never seen it anywhere, at any price. Generally, the only Cramps CD you ever see in any shop is the 1984 compilation Bad Music For Bad People. Which isn’t a bad listen, but sometimes you want to hear the original album, right?

This is also the first album where Lux and Ivy did a major share of the songwriting chores, although some of the most entertaining ones are the remakes of obscure oldies. Like bruising versions of “Green Fuz,” “Goo Goo Muck,” “ Primitive,” and an especially rousing version of Bobby Nolan’s “The Crusher.” The Lux/Ivy penned tunes like “Voodoo Idol,” “Don’t Eat Stuff Off the Sidewalk,” “Can’t Find My Mind,” and “The Natives Are Restless” don’t lag far behind in terms of entertainment value. The performances are incendiary to say the least!

This disc is hard to find, but well worth the price. And with the virtual invisibility of the title for online streaming—no Tidal or Qobuz—worth grabbing if you stumble across one or see a copy online. Highly recommended!

I.R.S. (UK), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Neil Young - Trans

Things were really beginning to gel with my soon-to-be wife and I in 1982. Both of us were huge Neil Young fans, her especially—she was a student at Kent State University when the shootings happened, and the Neil Young-penned “Ohio” really struck a chord with her on a personal level. We’d never seen Neil live, and when I found out he was touring solo in support of the new album Trans, I got tickets for a show at the University of Georgia coliseum. I already had the album, which was unlike anything that Neil had ever done before—he was just beginning his phase of concept-related albums that spanned the Eighties into the Nineties and forward. Anyway, the concert was fabulous, and Neil performed Trans virtually in its entirety with minimal accompaniment. And when he performed “Ohio” accompanied only by his acoustic guitar, it was probably the most spine-chilling moment I’ve ever experienced at a live show.

Although Trans came out at the dawn of the CD era, it was never released as a domestic CD. I had the album at one point, but had basically pretty much forgotten about it until I stumbled across this German Geffen Records import CD at an antique mall—for $2! It starts out with a kind of rockabilly number “Little Thing Called Love,” which was probably more in line with the upcoming album, the retro Everybody’s Rockin’. From that point, all bets are off, with computer and synthesizer enhanced numbers like “Computer Age,” “We R In Control,” “Transformer Man,” and “Sample and Hold.” And more straightforward rockers like the remake of “Mr. Soul” and the sprawling “Like an Inca.”

This is one of those titles that I was happy to get a few years back, and a great addition to my music server and Neil Young collection. Because it was virtually impossible to find anywhere other than on an LP—try finding a decent, clean pressing with a pristine outer jacket. Nowadays, it’s available on all the major streaming services, so no need for the search, unless you just really desire having a copy. But if you stumble across one at a reasonable price, I’d definitely recommend grabbing it. And at least take a listen on Tidal or Qobuz, it’s a real blast from the past!

Geffen Records (Germany), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Header image courtesy of

Neil Young - Trans

Things were really beginning to gel with my soon-to-be wife and I in 1982. Both of us were huge Neil Young fans, her especially—she was a student at Kent State University when the shootings happened, and the Neil Young-penned “Ohio” really struck a chord with her on a personal level. We’d never seen Neil live, and when I found out he was touring solo in support of the new album Trans, I got tickets for a show at the University of Georgia coliseum. I already had the album, which was unlike anything that Neil had ever done before—he was just beginning his phase of concept-related albums that spanned the Eighties into the Nineties and forward. Anyway, the concert was fabulous, and Neil performed Trans virtually in its entirety with minimal accompaniment. And when he performed “Ohio” accompanied only by his acoustic guitar, it was probably the most spine-chilling moment I’ve ever experienced at a live show.

Although Trans came out at the dawn of the CD era, it was never released as a domestic CD. I had the album at one point, but had basically pretty much forgotten about it until I stumbled across this German Geffen Records import CD at an antique mall—for $2! It starts out with a kind of rockabilly number “Little Thing Called Love,” which was probably more in line with the upcoming album, the retro Everybody’s Rockin’. From that point, all bets are off, with computer and synthesizer enhanced numbers like “Computer Age,” “We R In Control,” “Transformer Man,” and “Sample and Hold.” And more straightforward rockers like the remake of “Mr. Soul” and the sprawling “Like an Inca.”

This is one of those titles that I was happy to get a few years back, and a great addition to my music server and Neil Young collection. Because it was virtually impossible to find anywhere other than on an LP—try finding a decent, clean pressing with a pristine outer jacket. Nowadays, it’s available on all the major streaming services, so no need for the search, unless you just really desire having a copy. But if you stumble across one at a reasonable price, I’d definitely recommend grabbing it. And at least take a listen on Tidal or Qobuz, it’s a real blast from the past!

Geffen Records (Germany), CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Header image courtesy of

None of the students ever cursed at me again. The shock value was gone: Their words had become meaningless sounds used in a musical way. The students discovered I was able to curse just like them, even if I wasn't from their part of town. In fact, the rest of the year was totally enjoyable and productive. Instead of ignoring me they all wanted my constant attention, expressed wonderful creativity and did, after all, end up learning through the arts.

Then there was the time I taught music as a visiting artist at ASCEND (an Arts-Integrated Expeditionary Learning Outward Bound) elementary school in Oakland, CA. One of the fourth grade classes I was assigned to also had a student with behavior problems. He didn't curse but was disruptive, called constant attention to himself, couldn't sit still, and more often than not was sent out of class for short periods of time to work on his assignments in the hallway or an empty room. If it was my class I probably would have done something like that, too, if one student was interfering with my teaching day after day.

But as a visitor who spent very little time with the students I was able to see a different side of him. When I was carrying musical instruments back and forth, he offered to help. When I asked for a volunteer to lead an activity, his hand went up immediately. In contrast to Gertrude Stein's “there is no there there,” there was something there in Oakland: a boy with energy, enthusiasm, and needs that didn't quite fit into a traditional classroom setting. Disruptive, yes. But if I needed someone to conduct a curse-free chant composed by his classmates he was right there, ready to go.

When the residency was over I visited the school one last time to say good bye. I especially wanted to say something to that disruptive student. He had been in trouble again and wasn't in class but I found him in the hallway, scowling as usual. I told him even though he had to learn to control himself and work with others he had terrific energy, was very helpful and careful when carrying the instruments, and always ready to try something new. I was sure he was going to do great things in the future.

For a moment he seemed embarrassed. Then his face lit up and he smiled from ear to ear. A big, broad, beautiful smile. He was told he had value. And I'm not sure anyone had ever said that to him before.

Header image courtesy of

None of the students ever cursed at me again. The shock value was gone: Their words had become meaningless sounds used in a musical way. The students discovered I was able to curse just like them, even if I wasn't from their part of town. In fact, the rest of the year was totally enjoyable and productive. Instead of ignoring me they all wanted my constant attention, expressed wonderful creativity and did, after all, end up learning through the arts.

Then there was the time I taught music as a visiting artist at ASCEND (an Arts-Integrated Expeditionary Learning Outward Bound) elementary school in Oakland, CA. One of the fourth grade classes I was assigned to also had a student with behavior problems. He didn't curse but was disruptive, called constant attention to himself, couldn't sit still, and more often than not was sent out of class for short periods of time to work on his assignments in the hallway or an empty room. If it was my class I probably would have done something like that, too, if one student was interfering with my teaching day after day.

But as a visitor who spent very little time with the students I was able to see a different side of him. When I was carrying musical instruments back and forth, he offered to help. When I asked for a volunteer to lead an activity, his hand went up immediately. In contrast to Gertrude Stein's “there is no there there,” there was something there in Oakland: a boy with energy, enthusiasm, and needs that didn't quite fit into a traditional classroom setting. Disruptive, yes. But if I needed someone to conduct a curse-free chant composed by his classmates he was right there, ready to go.

When the residency was over I visited the school one last time to say good bye. I especially wanted to say something to that disruptive student. He had been in trouble again and wasn't in class but I found him in the hallway, scowling as usual. I told him even though he had to learn to control himself and work with others he had terrific energy, was very helpful and careful when carrying the instruments, and always ready to try something new. I was sure he was going to do great things in the future.

For a moment he seemed embarrassed. Then his face lit up and he smiled from ear to ear. A big, broad, beautiful smile. He was told he had value. And I'm not sure anyone had ever said that to him before.

Header image courtesy of

John Lennon's 1965 Epiphone Casino.

John Lennon's 1965 Epiphone Casino.