The Replacements – Dead Man’s Pop

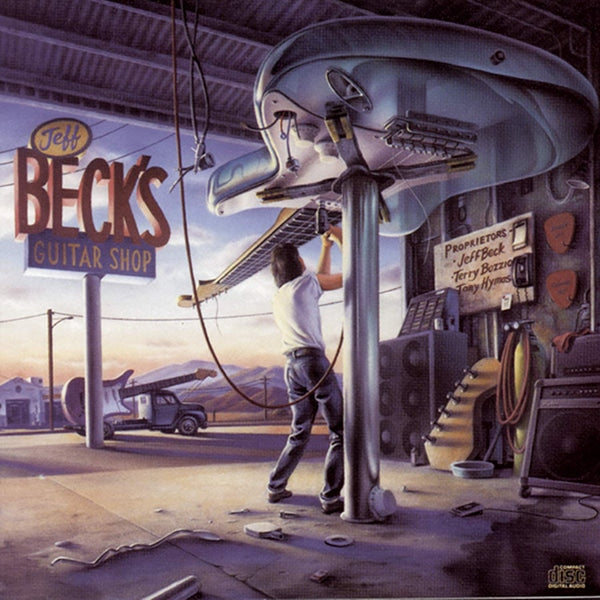

1989 found the Replacements either on the verge of a major commercial breakthrough or possible self implosion. Their new album Don’t Tell a Soul had just been released, and was a surprise commercial hit. “I’ll Be You” became their only song to ever chart, landing at number one on Billboard’s Modern Rock chart—how could things possibly get any better—or perhaps be any worse? Paul Westerberg was completely beside himself.

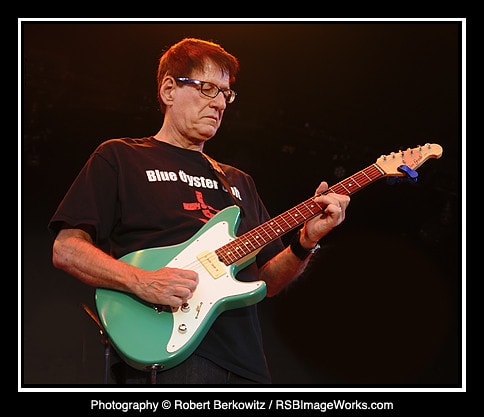

They’d spent months at Bearsville Studios in New York working on Don’t Tell a Soul, but were growing tired of constantly battling original producer Tony Berg. And Paul Westerberg was completely dissatisfied with the sound. A change of venue and producers was definitely in order, and the ’Mats relocated to LA’s Cherokee Studio under the helm of rising producer Matt Wallace. Wallace’s tapes had a spare but punchy sound that imbued much of the proceedings with a “live in the studio” kind of feel. The band responded with a superb effort musically, one that sounded much more like they were about to abandon their confrontational approach to the music business and embrace the stardom that had always eluded them. However—even though Matt Wallace had the record mixed and essentially in the can, the powers at Sire Records decided that they needed to bring in a more bankable producer to create the final mix. Someone with a more radio-friendly ear that would deliver the slick, polished sheen that would sell lots of records. Chris Lord-Alge was designated for the task; known for compressing the hell out most everything he mixed for luminaries like Madonna and Bruce Springsteen, his house sound sold albums. From Sire’s point of view—mission accomplished.

Paul Westerberg was pissed. The album didn’t sound anything like Matt Wallace’s tapes, and Westerberg was quite vocal to the music press about his disdain for the album’s sound, sounding to him “like everything else on the radio.” Although the Replacements soldiered on for a couple of more years, by 1991, the dream was over. The ’Mats had quite the history of absconding with their original tapes (actually tossing the classic Twin Tone label tapes from their first three albums into the Mississippi!), and no one really had any idea what had happened to Matt Wallace’s tapes of the Don’t Tell a Soul sessions. Until, almost miraculously, they were discovered in Slim Dunlap’s basement decades later. Slim’s wife called Replacements biographer Bob Mehr and asked him to come pick them up!

And so we have Dead Man’s Pop—the working title for Don’t Tell a Soul, and presented here as a four-CD/one LP boxed set. Only two of the seventy-one tracks found in the set have ever seen the light of day. Among the treasure trove discovered was Matt Wallace’s original mix, and while a bit rough, it served as the template for what’s been delivered as the ultimate version of the album on the first CD and 180 gram LP. Matt Wallace was contacted about the project, and was totally stoked to remaster and remix the tapes to restore his original vision for the album, along with the inclusion of demos and outtakes from the sessions. A second CD contains the original Bearsville recordings; while understandably inferior to the Wallace tapes, they’re still an instructional listen, nonetheless. And none other than Tom Waits—who apparently was a big fan—dropped in and guested on a selection of tunes, where he and Westerberg just basically got really blasted and cranked out the jam. Two discs contain a 1989 concert at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee that finds the ’Mats in very good sound, indeed—sounding much more polished and professional than most anyone generally ever gives them credit for. All in all, for Replacements completists, the set is the perfect collection of oddities and curiosities, and the perfectly realized version of Don’t Tell a Soul we’ve all been waiting for.

All my listening was done through Roon with Tidal’s 24/96 MQA version, which sounded truly superb. Matt Wallace’s remix of the album is an absolute revelation, and the sequencing of the songs has been restored from Lord-Alge’s bastardization to their original order. The ’Mats had mellowed and matured by this point, with most of Paul Westerberg’s songs taking on more of a “jangly guitars” kind of sound as opposed to the raucous days of the early Twin Tone records. The sound of the new mix is remarkably even; incredible, considering that the Lord-Alge version of Don’t Tell a Soul is definitely the most maligned Replacements album ever. And the liner notes are adapted from biographer Bob Mehr’s excellent book Trouble Boys; if you haven’t read the book, order one now—it’s an essential read for all ’Mats fans. This outstanding set is very highly recommended!

Rhino Records, 4 CDs/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Apple Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Elbow – Giants of All Sizes

Manchester band Elbow are pop darlings in their native England, with each of their last two albums having shot to number one on the charts; that includes their latest release, Giants of All Sizes. Which is their eighth studio album over a twenty-year period, and has me asking: how is it that I’m totally unfamiliar with their body of work, which falls somewhere in the prog/alt pop/dream pop spectrum. Witness the sprawling seven-minute opening track “Dexter & Sinister,” in which singer and bandleader Guy Garvey opines in his velvety voice that “loss is a part of a life this long…with the heaviest heart jackhammering within me…and I don’t know Jesus anymore.” The song—and the album, in general—laments the current state of an increasingly divisive and inhospitable England in the age of Brexit. It’s a glorious song, with quirky meter changes and an almost grindingly propulsive beat that suddenly gives way to an atmospheric, wordless coda sung by guest vocalist Jesca Hoop that wouldn’t sound too out of place on a Pink Floyd album. And that’s only the first song!

This is Elbow’s most overtly political album ever; in “White Noise, White Heat” Garvey sings “the white noise of the lies, the white heat of injustice has taken my eyes; I just want to get high.” We might want to think the current age of Trumpian madness is restricted to our side of the pond, but longing for a simpler, less complicated existence is an almost universal truth across diverse cultures and great distances. When Garvey sings in the chorus of “Empires” that “empires crumble all the time…pay it no mind…you just happened to witness mine,” he’s referencing his own struggles as well as the bigger picture. Yes, there’s a definite philosophical/political undercurrent here, but Giants of All Sizes is also filled with remarkably good pop songs with often proggy accompaniments that makes for a seriously enjoyable listen.

I did all my listening via Roon with Tidal’s 24/88 MQA version of this album; the sound quality was superb throughout. This was an eye-opening exposure for me to the genius of Guy Garvey and Elbow, and hearing Giants of All Sizes has only increased my desire to dig more deeply into their available catalog. Prior to recording this record, Guy Garvey grappled very hard with the passing of his father and the mourning period involved; the 2017 bombing in hometown Manchester and its aftermath; and what Garvey describes as the “absolute cultural disaster” in the wake of Brexit. Despite having all that on a very full plate, both he and Elbow have crafted an excellent album that satisfies both musically and emotionally. Very highly recommended.

Polydor Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Deezer)

Kanye West – Jesus is King

I saw a recent online article about upcoming trends that are most definitely going to happen. Among them was “Most Likely to Start His Own Religion”, which will feature Kanye West as the new Yeezus. It most definitely has happened; he appeared a week or so ago with his “Sunday Service” tour at the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church here in Atlanta. From what I could tell from the local news coverage, it was a highly orchestrated publicity stop and photo op for his new album, Jesus is King. Where Kanye delivered not only his reaffirmation of his embrace of Christianity, but also an exclusive opportunity for the 600 or so onlookers to aquire some high-dollar Jesus is King merch afterwards in the church lobby. I expect Kanye will replace the “Jesus” part with “Yeezus” in his not-too-distant messianic future.

Are people really taking this seriously? I was raised in the backwoods of rural North Georgia, only a generation apart from snake-handling, fanatical religious evangelicals. As a kid, my family once attended a large-scale family reunion in South Carolina, where at some point, someone broke out the rattlesnakes—and three people were bitten. Of course, the logic of the “true believers” is that, if bitten—and you live—well, then, you’re obviously right with God. Otherwise…you get the picture. Later on, in my late teens, I also had the experience of attending a full-blown frenzy of an event starring The Mighty Clouds of Joy at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in downtown Atlanta; think, James Brown’s performance in The Blues Brothers. Kanye has perhaps a shred of the charisma of James Brown! My hands-on experience with religious fundamentalism makes it personally hard for me to place much faith in Kanye’s track record of sincerity in his approach to just about anything, especially religion. Even if he’s only singing about it.

Kanye’s struggles with bipolarism are widely documented; I saw another online article where the author—who is also bipolar—set forth a deep connection between bipolarism and religious fervor. If God rains down his (financial) blessings on the West/Kardasian compound, I expect that will probably be close enough to redemption for Ye. You pays your money, and you gets what you pay for—I can choose from fourteen over-the-air channels and get a close (maybe even gold-plated!) approximation of the Yeezus on my TV screen. I’d pass on this one.

Getting Out Our Dreams II/Def Jam Recordings, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music)

Matthew Snow – Iridescence

Iridescence is bassist and composer Matthew Snow’s self-produced debut as a leader, although he’s been a fixture on the New York jazz scene for the last seven years. He composed all the tunes here, and they’re played in a bit of a twist from the typical straight-ahead style, eschewing the seemingly mandatory inclusion of a piano or tenor sax to anchor the proceedings. Instead, going for a sextet built around Daisuke Abe on guitar, Joe Doubleday playing vibes, David Gibson on trombone, Clay Lyons on alto sax, Wayne Smith playing drums, and, of course, Matt Snow’s acoustic bass. Snow very generously gives all the players plenty of room to stretch out, and he mostly avoids the spotlight, allowing the contributions of the sidemen to shine throughout. While Iridescence mostly consists of traditional hard-bop fare, a few ballads are thrown in for good measure.

You get the impression that these guys have played together for some time, and know each other very well. The playing on Iridescence is of a very high caliber throughout, seamlessly flowing back and forth from group choruses to individual solos. The spotlight is generally focused on either trombonist David Gibson, who solos to spectacular effect on both the moody ballad “Brood” and the album’s closer, “Venus.” Clay Lyons’ alto sax takes the fore on the excellent “Jealousy”, which is also one of the few tunes where Matthew Snow steps into the spotlight with a brief solo. And Joe Doubleday’s vibes are heavily featured on almost every tune—more about that in just a moment.

I fully understand that these are tough times for musicians of any genre, and that all the traditional music distribution modes have gone by the wayside now that streaming is becoming the norm. Playing gigs, and maybe selling their CDs are the only sure ways of making any kind of sustainable income in the current age. I wouldn’t be surprised if many of the musicians here still work day jobs; following their passion for music after hours. I really do feel for these guys, especially jazz musicians.

That said, this is one of the most poorly mixed and/or recorded jazz outings I’ve heard in a really long time. A couple of things probably happened here; it was probably produced on a shoestring budget, and the recording equipment and studio (if any) seem to have been makeshift. Nothing wrong with recording an album in your own home (ask Rudy Van Gelder about that!), but it’s great to have someone onboard who has a really good sense for what good recorded sound should be. Example: I mentioned about Joe Doubleday’s vibes being so prominently featured on Iridescence; they literally occupy the entire right channel for the entire recording. He can’t help but get the spotlight—there’s no one else there to share it with him. And on the first three tunes—and two others later in the set—everyone else on the record (save for Matthew Snow) is in the left channel. Far left. Matthew Snow’s bass is firmly anchored in the middle of the soundstage, but it’s almost a ghost effect; only in a couple of tunes, the aforementioned “Brood” and “Jealousy” can you even hear his fingers plucking the strings. The recording has plenty of bass, but it has an almost phantom quality—you’d virtually never know Matthew Snow was occupying a position in the soundfield.

The first three tunes are so heavily balanced to the far left side that I was just about to give up on Iridescence. When suddenly, on track four, “Brood”, David Gibson’s remarkably good trombone sound emerges squarely from the center—and the overall sound becomes glorious! This happens again on Gibson’s solo on the closing tune, as well as Clay Lyon’s fabulous alto turn on “Jealousy”. Those three songs alone give a completely different impression of this recording, and I was listening on the new Magneplanar LRS loudspeakers, which give most recordings about as much of a “you are there” sound as literally possible.

I really don’t mean to be hard on these guys; in artistic terms of the group effort and the quality of playing, Iridescence is a smashing success. With a more experienced hand at the controls, it could have been a complete triumph. I actually ripped the CD using dB Poweramp, and converted the sound to mono; it sounded not at all unlike a classic wide-mono Blue Note session from the sixties. And much less distracting; oh, for what might have been! This album doesn’t actually drop until later this month, so try looking for it in a few weeks.

Self produced, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, CD Baby, Apple Music)

Guillaume Muller – Sketches of Sound

Guillaume Muller, born and raised in Paris, began playing guitar as a teen; eventually he followed his dream to Boston, enrolling in the prestigious Berklee College of Music. After graduating in 2015, he then moved to New York, where he’s been playing and teaching for the last four years. Regularly playing with the NYU Jazz Orchestra and the NYU Wayne Shorter Ensemble. And performing at iconic NYC venues like The Blue Note, Minton’s, and Bar Lunatico, and even performing live on WBGO—The Jazz Source of New York. Oh, and by the way, he also completed his Master’s degree in Jazz Studies from NYU Steinhardt—yeah, I’d say he’s been pretty busy!

The sessions for Sketches of Sound were held at the James L. Dolan Studios in NYC earlier this year, and the tapes were recorded, mixed, and mastered by Tyler McDiarmid. The quintet consists of Nino Wenger on alto sax, Jim Funnell plays piano, Gui Duvgnau on acoustic bass, and Josh Bailey on drums, rounded out by Guillaume Muller’s outstanding contribution on guitar. These guys are all crack musicians, and they’re all given plenty of room to solo and stretch out. Of the seven tunes included here, six are self-penned by Muller, with the seventh being a very clever reworking of the classic Arthur Schwartz/Howard Dietz standard “Alone Together”. Nearly unrecognizable from any other recorded version of the tune I’ve heard, I had to hit the replay button repeatedly on my disc player to make sure I was listening to the correct track! Despite most of the tunes being originals, they all have a ring of familiarity to them that makes them very accessible.

Sketches of Sound is Muller’s debut CD as a leader, and it’s an absolutely textbook example of a self-produced recording that not only includes magnificent performances from all the players, but is offered in audiophile-quality sound as well. Listening through the Magneplanar LRS’s, I was absolutely blown away by the stunning realism of the stereo image. And the overall quality of the recording is staggeringly good; each of the players occupies a very real and palpable position in the soundstage—they’re literally right there in the room with you. All of the instruments are incredibly dynamic; the drums are especially percussive, and the cymbals just absolutely shimmer. This is perhaps the finest jazz combo recording I’ve had the pleasure to audition so far this year!

If this disc is any indication of Guillaume Muller’s talents, he has a very bright future ahead of him. Check out Sketches of Sound, if you get the chance—it comes very highly recommended!

Self produced, CD (download/streaming from Bandcamp, Tidal, Amazon, Spotify, Apple Music, Google Play Music, Pandora, You Tube, Deezer)