I’ve just started working with an independent jazz distributor from NYC, Jim Eigo with Jazz Promo Services. I’m highlighting several of his recent and upcoming releases in this issue; there are a ton of independent jazz artists out there that get next to zero mainstream coverage. And deserve so much better than that. I hope you enjoy!

Dave Miller Trio – Just Imagine

The Dave Miller Trio are regulars on the jazz club scene in the San Francisco/Northern Californa beat. A New Yorker by birth, Dave started plinking the ivories on the family piano at age three, and trained as a clasical musician into his teens. When he suddenly shifted gears and followed his love of jazz, slumming ever since nightly in small clubs, with his day job as a lawyer paying the bills. While his discography consists of a few albums as a leader, most of his recorded work has been as part of the backup band to talented Bay Area jazz singer Rebecca DuMaine—who also happens to be Dave’s daughter!

Dave’s new album, Just Imagine, is a tribute to one of his idols, the jazz legend George Shearing; this year marks the centennial of his birth. Just Imagine is not so much a compilation of songs made famous by Shearing, but more a selection of rarities and other obscure songs that Shearing often performed in his shows. The trio nails their performances on that account; despite my having a fairly extensive jazz collection, there are at least a half-dozen songs here that I’m completely unfamiliar with! From the opening notes of Billy Taylor’s “One for the Woofer”, it’s obvious that Dave Miller’s intricate playing is not at all derivative of any one particular style: he’s got some great chops! Another great tune—but also previously unknown to me—is Ray Bryant’s “The Bebop Irishman”, where there’s some really swinging interplay between Miller and drummer Bill Belasco, who really pounds those skins! George and Ira Gerswin’s “A Foggy Day” starts out like many a recording, where Dave Miller offers a contemplative opening on piano; you’re expecting the rest of the trio to join in. But they never do, it’s an entirely solo reading, and Dave Miller really shows his craftiness and creativity here—did I mention that this guy completely swings, and can really play the piano? And I love any period Bill Evans; especially one of his last recordings, You Must Believe in Spring. Where he starts out deliberately, then shifts into a really upbeat version of the Michel Legrand-penned title tune. Here, Dave Miller follows Evans’ lead, but then continues the tune in a very movingly pensive and contemplative reading that’s reminiscent of Bill Evans, but rendered entirely in Dave’s own style. It’s definitely one of the highlights in an album of many.

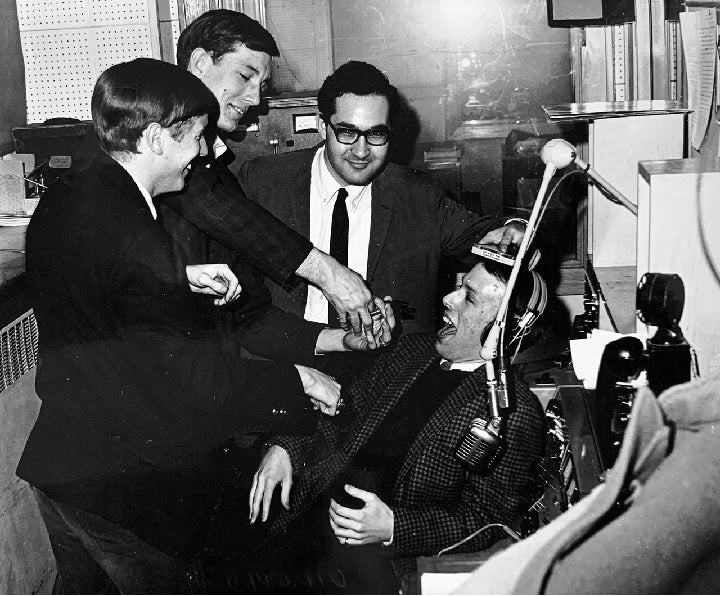

I have to be perfectly honest, when I saw the picture of the three members of the trio, I immediately assumed that this was going to be an album of classic cocktail jazz. Boy, was I wrong! I have no idea of Dave Miller’s age or the age of either bass player Chuck Bennet or drummer Bill Belasco, but they appear from their photos to have a few miles on them—you’d never know that from the often rapid-fire playing througout this excellent album. They definitely seem to know each other’s playing very well; the interaction between them is just about seamless on every tune. And Dave Miller’s piano is definitely the star here; he plays with a style that’s all his own, and it’s totally obvious that his love of jazz has taken him to the next level. And hey, I noticed that several of Dave’s daughter’s albums are available for streaming on Tidal (also on Summit Records)—I took the liberty of checking out Dave’s playing in a backup setting. Really enjoyable, and Rebecca DuMaine is no slouch either—she’s an amazing singer, and fortunate to have such a talented pianist at her disposal. Just Imagine is very highly recommended. If you’re a fan of classic jazz trio settings in a high-energy, Shearingesque style, it’s not to be missed.

Summit Records, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify)

Gretje Angell – … in any key

LA-based Gretje Angell is a jazz vocalist whose dad and grandfather were both jazz drummers. She actually spent a considerable amount of time in her youth as the defacto roadie for her dad, Tommy “The Hat” Voorhees, who was a prominent fixture on the Akron, Ohio jazz scene. My wife is from Akron, and I’ve always been fascinated by just how many talented singers and musicians seem to pour forth from such a seemingly unlikely place. A transplant to the west coast, she’s been active on the LA jazz scene for some time now, singing with big-band units like Jack’s Cats, the Ladd McIntosh Swing Orchestra, and Glen Garrett’s Big Band. In her spare time, she also sings with the Los Angeles Metropolitan Opera Company. Pretty impressive resume!

It’s taken her a little while to get to this point, having a bit of a battle overcoming stage fright. But …in any key is her debut album, and at only a tad over 36 minutes, it’s actually more of an EP. Gretje says that when she gigs, she imagines her late father sitting in the back of the club and it helps calm her nerves. The album was produced by guitarist Dori Amarilio; he plays on every track, and his mastery of the Brazilian oeurve gives many of the songs here a Latin feel that spans the genres of Bossa Nova, Afro-Cuban, and Bop. The album gets its title from Gretje’s description of Dori’s uncanny ability to play any jazz standard, in any key, and at the drop of a hat. Her singing definitely shows her embrace of Latin rhythms, and she sings with a voice that pretty much defies close comparisons to anyone else out there. We listen to a ton of jazz singers here at home—with a seemingly disproportionate emphasis on female vocalists (my wife Beth would insist it’s my personal infatuation with female singers). As …in any key played, Beth kept insisting, “okay, she sounds just like”….and I’d follow with, “yeah, she’s reminiscent of”….but neither of us could quite get a handle on an accurate comparison to her sultry stylings. Gretje Angell scats on a lot of song intros and throughout a lot of bridges; the scatting is a tad similar to Melanie Gardot’s, but their voices are really nothing alike. Gretje’s scatting is very fluid and adds a certain playfulness and an increased level of interest to her song selection. I once got yelled at by the agent of another LA-based jazz singer when I described his client’s often over-the-top scatting as annoying.

There’s really not a weak moment musically on …in any key; and I truly find this album to be very emotionally involving. Gretje Angell takes songs like the Peggy Lee chestnut “Fever” and presents the tune with a swinging Latin delivery that gives a completely different dimension to a song that’s rarely presented outside the box and in a manner like this. There are a few straight-ahead readings here; among them is a tune popularized by Chet Baker, the classic “Deep In a Dream”; the strings in the background are totally apropos and Dori Amarilio’s spare and subtle guitar is the perfect accompaniment to Gretje’s smoky-sweet interpretation. There’s also the Duke Ellington gem “Do Nothing Till You Hear From Me”, which Gretje delivers in her own style without attempting to overshadow the inimitable Ella Fitzgerald’s classic version. And Gretje rips through a rapid-fire half-sung, half-scatted offering of Jobim’s “One Note Samba” that’s absolute ear candy. This is an impressively enjoyable debut album of great tunes that Gretje Angell manages to make entirely her own.

I do have a couple of minor quibbles with the recording—and that has no reflection on the performances at all, which are stellar. First of all, there are a couple of bad edits/mastering errors in places, where it seems the opening of a track is ever-so-slightly truncated. It’s slight, but perceptible. And there’s a pretty glaring mastering error between tracks 1 and 2, where the ending of track 1 (“Our Love is Here to Stay”) unintentionally jolts jarringly into the beginning of track 2 (“Im Old Fashioned”), also slightly truncating the opening of the song. It happens on both the CD and my rip of the CD; if you select track 2 for playback from the beginning, everything is okay. But if you allow the music to play through, the mastering error is obvious every single time.

The more egregious error for me is that the vocal track is mixed at a higher level than that of the remaining players; it’s such that it gives her voice an unnaturally oversized presence. Now don’t get me wrong here—I’m totally all about the vocal track being absolutely front and center of the music—but it’s just a little over the top here. Gretje Angell has an amazingly sultry voice that can easily carry the music without any level boosting; the engineer just needed to dial the vocal track level back a touch during the mixing session. Fortunately, my PS Audio DAC has several digital filters to choose from, and one of them actually helped to present a slightly more realistic and believable representation of the players and singer in a real space.

I don’t wan’t my criticisms of the recording to in any way diminish Gretje Angell’s lyrical and emotional performance on …in any key. Her singing here is so polished, it’s almost impossible to believe that this is her debut album. As an audiophile who also happens to be a music critic, unfortunately, I may occasionally tend to allow my evaluation of the recording quality to perhaps overshadow my impression of the musical performance. The performances here are superb, and this is truly a very good album; it could easily have been a great one with a little more care at the control panel.

Grevlinto Records, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Apple Music, iTunes, Tidal, Spotify)

Lyn Stanley – Favorite Takes: London With a Twist, Live at Bernie’s

Lyn Stanley is probably best known among audiophiles as a near-constant fixture at most of the popular audiophile shows like Chicago’s Axpona, the Rocky Mountain Audio Fest (RMAF), and the California Audio Show. At the shows, she’s often seen working the sales floor while plying her wares, or performing occasionally. She records with the very best musicians and producers, with the likes of Al Schmitt, Bernie Grundman, and Gus Skinas frequently showing up on her album credits. Her LPs, limited edition LPs, SACDs and the like litter the banners of audiophile retailers like the Elusive Disc and Acoustic Sounds—which is actually quite amazing. Less than a decade ago, she was a retired marketing executive who had no professional singing experience—or any singing experience, for that matter! There’s a very well-written article from a couple of years ago on Part Time Audiophile that details her very unusual and unlikely path to audiophile fandom; you can read that excellent article here. Hey, she’s making it work for herself, and selling quite a bit of product—I’ve seen estimates of upward of $400k in sales.

Lyn Stanley is obviously a devotee of revered singer Julie London’s repertory, and Lyn’s last couple of albums have paid tribute to that legacy. Those albums included London Calling: A Toast to Julie London, and the follow up, London With a Twist, Live at Bernie’s, which was recorded direct-to-disc without overdubs or other embellishments. The Bernie referred to in the title is, of course, legendary producer Bernie Grundman. Julie London was fond of recording her stylized versions of current popular songs rendered as jazz standards, and Lyn Stanley basically follows suit here. With some of her songs in homage to Julie London’s recordings of standards, while other selections show Lyn’s adaptations of more current fare.

The disc we’re reviewing here is the very recently released third iteration in that series, Favorite Takes: London With a Twist, Live at Bernie’s, where Lyn’s chosen favorite takes from that session are presented in two completely different formats on an SACD disc. Tracks 1-12 are comprised of a 1X DSD (DSD 64) needle-drop transfer of the analog test pressing from the direct-to-disc session. The needle-drop was created using a Clearaudio Master Solution turntable, a Lyra Kleos cartridge, and the brand new PS Audio Stellar Phono Preamp. The needle-drop tracks purport to offer playback that’s pretty close to what you could logically expect to hear during analog playback of the direct-to-disc LP.

Tracks 13 and on are the same 12 tracks taken from the 1X DSD feed of the live event directly from the Sonoma recording console to reel-to-reel. This SACD basically represent a live concert recording, with the recording made under the most optimal conditions possible. Even though there’s a hybrid CD layer available on the disc, for my listening and evaluation, I used only the SACD layer of the disc provided to me by Lyn Stanley. The standard CD layer sounds good as ripped to my digital music server via the Sonore Signature Rendu SE that’s currently in my system, but doesn’t touch the realism presented by the SACD tracks.

I have to admit that right out of the gate, I’m probably a bit prejudicial and conflicted with regard to Lyn Stanley in concept; I kind of object on a certain philosophical level to artists that are considered an “audiophile” entity, as such. There’s a ton of “audiophile” music out there that I pretty much consider complete, soulless crap. That said, while the vast majority of artists I listen to are the ones I simply enjoy listening to on a musical basis, there are a handful of so described “audiophile” albums that still push all of my buttons. Like Jennifer Warnes’ album Famous Blue Raincoat. Regardless of how that record gets damned by the naysayers, I still freaking love it! Even the lowly CD of that performance offers a level of artistic, emotionally involving enjoyment and superb, audiophile-quality sonics that’s irresistible.

I got a new SACD player a couple of months ago; it’s a Yamaha BD-A1060 universal player, and it’s maybe the best digital disc player I’ve ever owned. I’ve been listening to digital discs recently almost with the same frequency as digital files on my music server. My old Oppo disc player died about four months ago, not long after that painful death, I stumbled onto a sealed SACD copy of Lyn Stanley’s Moonlight Sessions, Volume I. At a thrift store, for one dollar. Holy crap, a freaking Lyn Stanley SACD for a buck—maybe now I can find out what all the hooplah is about! Of course, not having a functional SACD player, the best I could do was rip the CD layer to my music server, and well—I just wasn’t getting the hooplah. I didn’t hate the performance, but I wasn’t blown away, either. Lyn Stanley seemed, for me…more than just a tad emotionally detached from the songs. I decided to refrain from completely passing judgement until the disc could be heard in full resolution on a high res player.

On to the task at hand: London With a Twist via the new Yamaha universal player. Lyn Stanley has a deep, dark, almost husky soprano voice; her voice as an instrument is really quite impressive. And her instrumental accompaniment is, to say the least, superb. But as perfect as these recordings are, her portrayal of these chestnuts just doesn’t quite sound, well—believable to me. There’s a lack of emotional investment in the songs. A few of the songs here, like “Route 66”, “Let There Be You”, and “Love Letters” make for campy, enjoyable listening. As for the rest, well, they didn’t imbue in me any desire to do much of anything, especially to partake in repeat listenings. In very sharp contrast, even when an almost universally lambasted artist like Diana Krall sings “Peel me a graaaaape, slow-ow-ow-ly”, I wanna get in my car right now and drive down to the farmers market! With me, it’s all about an emotional connection to the music, along with to-die-for sound. I’m not getting the emotional connection here.

The direct-to-disc LP that preceded this SACD, London With a Twist, Live at Bernies, retails for almost $125, and is typically sold to owners of mega-buck turntables looking for the absolute demonstration disc for their system. This SACD provides a lower priced (about $40) alternative; and A/B testing between the needle drop and pure DSD tracks is quite revealing and informative. While the pure DSD tracks rank among the finest stereo SACD sound I’ve ever experienced, the needle drop tracks have an added realism that is shockingly good, even if it obviously doesn’t possess the same overall resolution and clarity of sound as the pure DSD tracks. Certain purchasers, obviously, will find the needle-drop’s allure very appealing.

By the way, I did take a listen to the SACD layer of the Moonlight Sessions, Volume I; truly excellent sound, but mostly uninvolving for me. Your mileage may vary with Favorite Takes: London With a Twist, Live at Bernie’s; if you’re looking for a lights-out demonstration disc, this may be just the ticket….

But the music still leaves me cold.

A.T. Music LLC, Hybrid SACD (download/streaming from Tidal, Spotify)