Two of the world’s leading chip manufacturers have recently announced moving on to 5 nm manufacturing. Nanotechnology and micromachining are becoming hot keywords in technical and scientific publications. Micro Electro Mechanical Systems are being built with tiny features of just a few dozen µm, finding application in highly specialized equipment “for the government”….With all this excitement, one would think we have only recently made such micro manufacturing possible!

When the National Association of Broadcasters first published their “NAB Audio Recording and Reproducing Standards for Disc Recording and Reproducing”, in 1942, they essentially called for exactly this level of manufacturing, which was routinely achieved since the end of the 19th century and had escalated into a large industry by the early part of the 20th century! Since the advent of electrical sound recording in the very early 1930’s, special machine tools, called disk recording lathes, were able to cut grooves 12.7 µm (0.0005″) deep, at a pitch of up to 300 LPI (lines per inch), modulated by sound. The faintest sounds, which could subsequently be audibly reproduced, were represented by amplitudes of mechanical displacement of a couple of nm! To put this into perspective, 1 nm = 0.000000039″ and the wavelength of visible light ranges from just over 700 nm at the red end to just under 400 nm at the violet end.

Not only was it possible to machine grooves on such a micro-nano scale, by traditional mechanical means, but it was already possible, in the 1930’s, to manufacture disk recording lathes and cutter head transducers, using good old fashioned traditional machining operations, attaining the required degree of accuracy, using the measurement instruments available at the time. None of that CNC, LASER, simulation software, micromachining, nanotechnology, ceramics, superconductors, additive picoalloys, blockchain…. Sorry, my random keyword generator just experienced a gap in the time-space continuum.

In fact, the Neumann VMS70, one of the most widely used disk mastering lathes of all time, introduced in 1970, was essentially the mechanical assembly of the Neumann AM31, introduced in 1931 as Neumann’s first lathe offering, along with a basic automation system to control the lathe’s cutting parameters. Likewise with Scully, who was already in business in 1920, making acoustic recording lathes prior to the invention of electronic amplification.The mechanical design of their lathe remained practically unchanged from 1930 to 1976, when the LS-76 was introduced.

Neumann and Scully, being the only two manufacturers remaining in business past the 60’s, are the better known names nowadays. But several other lathes had been and some even still remain in professional use, such as my modified Fairchild lathe from the early 1930’s, featured in the Vintage Whine column in Copper #89.

It is safe to say that the vast majority of the outstanding examples of vinyl records in existence, were cut on 1930’s technology.

Even motional feedback transducers had already been invented by 1937. The early design concepts proved so perfectly adequate, that no effort was ever expended in improving upon them. Even in the 70’s, the changes were mainly in the form of modern restyling, keeping the original mechanical features intact, while developing more advanced automation systems, allowing less skilled operators to cut functional records, lowering the labor costs, in line with the times.

By that time, there were several other sound recording technologies available, which were deemed more convenient (not to say cheaper) for many applications. With only two surviving manufacturers of lathes, the extreme accuracy required and the development of elaborate automation systems, a disk mastering system was by no means a small investment. These systems were unbelievably expensive, large, heavy and fragile. There were very few facilities in the world who could have one, very few skilled cutting engineers and almost nobody who could work on these machines, should repairs be required.

The situation was very different prior to the 1950’s. Jack Mullin had returned from the war with this most secret German technology, the Magnetophon, and it would still take a few years before tape machines would become widely available. Up until then, disk recording was generally seen as the most practical and viable form of sound recording for most applications. Not all applications involved music or any serious expectation of sound quality, enabling the use of simpler equipment. A major application for disk recording lathes was the requirement for radio stations in several countries to “log” their entire program. This was a huge boost for the lathe industry and a huge loss when this field eventually was taken over by tape recording equipment.

There was a time when nearly every industrialized nation of the world had at least one manufacturer of disk recording lathes. These were usually smaller and simpler systems, which were widely used in recording studios, radio stations, educational establishments and even in the homes of the more affluent, as “hobby” recording machines. There were several thousand people cutting records on a regular basis, although most of these were not intended for mass production. More commonly, one-off records were cut, rather than masters for subsequent processing. There were several facilities in every major city, offering to record radio jingles on to disk, copy the original disk to a few more disks, cut one by one and distributed to radio stations.

At the same time, there was the world of mass manufacturing by record companies, for sale to the general public. This again would start by cutting the “master” disks on a lathe. The bigger and more expensive lathes were generally reserved for “mastering” work. These masters would then be electroplated, to derive metallic “negatives”, which would still retain all the nano-scale groove undulations. A set of negatives, called “stampers”, would then be mounted in the molds of a steam-heated, water-cooled, hydraulic press, which would press multiple copies of the record.

In this sector, there were always far fewer lathes than presses and far fewer disk mastering engineers than press operators, since one set of masters could produce several sets of stampers and each set of stampers could produce at least a thousand records.

As magnetic tape recording replaced disk recording, the smaller and simpler lathes went out of vogue and their production ceased. The only sector where lathes were still needed was in the mass manufacturing of records, to cut masters. But there were many perfectly good mastering lathes already in use, built sturdily enough to run for centuries. The demand for lathes was, by now, rather small and the demand for new cutting engineers even smaller.

Aftermarket automation systems could be purchased from a few different sources and retrofitted to older lathes, keeping them up-to-date with the newest offerings.

All in all, there were probably around 150 cutting engineers remaining around the world. It went from cutting records being synonymous to sound recording, where everyone involved in sound recording was expected to know how to cut records, to it assuming the status of an obscure art, practiced only by very few behind closed doors in secret laboratories hidden deep under ground. As with anything of such rare nature, it became surrounded by hype and mythology.

The great paradox is that while vinyl records were seen as consumer goods, available in large quantities and at low cost, the tools and processes used in their manufacture were among the most accurate in existence, requiring considerable skill and expense. Even the final product itself was a precision instrument, similar in many ways to diffraction gratings for spectroscopy, though the latter were never intended as low cost consumer goods!

From this perspective, there were several “issues” with the vinyl record as a product for mass consumption. It was not actually that cheap to manufacture, due to the extreme precision required. It required skilled engineers to cut masters, who were in short supply, expecting a skilled engineer’s fee for the services.

The process did not lend itself to complete automation. The human factor could not be eliminated, as modern trends were dictating. The resulting product was large, heavy and sensitive, making it expensive to transport and store, taking up considerable display real estate in retail, making it impractical to manufacture at a convenient location (with a favorably inexpensive and preferably unskilled workforce) and ship all over the world from there.

While the engineers involved in their manufacture were really proud about the low product cost they had managed to achieve for such a complex process, the consumers and merchants were complaining about the “expensive” prices.

The times they did a-change and new technology was invented, making the consumer formats for the distribution of music progressively smaller, lighter, cheaper, less fragile, easier and faster to manufacture, more automated and less dependent on the human factor, up until the point when distribution formats entirely left the physical domain with its old-fashioned manufacturing processes behind… Easiest, fastest, cheapest, free…wait….what? Scully stopped manufacturing lathes by the late 70’s and Neumann stopped in 1985, shortly after introducing the Direct Metal Mastering system. Since then, nobody has designed or manufactured a new mastering lathe. The industry went the way of the dinosaur. Pressing plants either moved on to CD/DVD manufacturing or went out of business, or both. Lathes and record presses were sent to the crusher, or even in one famous case, dumped in the sea, where they still remain to date, appreciated by aquatic life forms keen on obsolete industrial machinery to breed inside.

Magnetic tape formats went the same way and even optical media are now fading out.

But then, magically, the vinyl record came back!

The author, inspecting a master cut on a heavily-modified 1940 Neumann-based system.

Some people were apparently immune to the general business short-sightedness at the time and had simply powered down entire pressing plants without disassembling them. These were promptly powered up again and were immediately overwhelmed with demand, running at full capacity. Presses and lathes were pulled out of barns, basements, yards, oceans, and deserts and repaired. A few years later, new presses were on offer. There are now at least four companies in different countries, manufacturing record presses and other record manufacturing equipment. Major audio equipment manufacturers are introducing new turntables and cartridges, while the “classic” brands are being bought up and the iconic models of yesteryear reissued.

But, what is up with lathes? No lathes yet. The entire industry is still running on 1930’s technology, which, in the hands of a suitably skilled engineer, can still sound unbelievably good. A new generation had to figure out, pretty much from scratch, how to make records. The knowledge and experience had nearly become extinct.

Compression molding (pressing) and electroplating (galvanics) are widely used in many other sectors for the economic mass production of consumer goods, so this was not as tricky to rediscover, hence the offerings of new equipment.

However, cutting micro-grooves to nano-scale accuracy, even in 2019, still remains quite a challenge. There are still very few disk mastering engineers around and the hype is hotter than ever.

Wizards and witches wearing pointy hats, complete with long cloak and pet dragon on shoulder, snow-white beard or long white hair, dragging on the floor of their cave (or was it a castle?) as they approach their medieval machines, smoking test tubes and little glass vessels containing fluorescent liquids all around, cauldron simmering over the fire, permanent fog even inside the alchemastering engineer’s laboratory, the occasional bat flying around at 78 rpm.

Poor Editor Leebs had to be parachuted off to the valley of eternal darkness, climb mountains, cross rivers and swim through the mote of my castle faster than the alligators, to then have to walk all the way back with this handwritten manuscript, if the vampire vultures don’t get him…

Ok, enough hype. You get the idea.

To dispel some of the hype, it is certainly not the case that there is no room for improvement. Engineers who would be capable of designing a new lathe, outperforming existing machines, definitely exist, even if usually found very gainfully employed in other sectors. It is not magic, just science, engineering, and craftsmanship. This is a perfect example of a process which has never actually reached a technologically-imposed limit. The limit to what can reasonably be achieved has always been and still remains economically imposed. The vast majority of commercial album releases on vinyl do not come anywhere near approaching the full potential of the medium, even to the limited extent in which this has already been explored, due to cost considerations.

But, this is not just about records. We urgently need a radical departure from the cheaper-cheapest-fastest-easiest mindset which has invaded the music industry, if we are to prevent technological, artistic, intellectual and even economic stagnation.

The first step in beginning a new project is constructing the pattern from which the fiberglass mold will be laminated. The above picture shows the various sheets of ¾” MDF (medium density fiber board), that is glued and clamped together.

The first step in beginning a new project is constructing the pattern from which the fiberglass mold will be laminated. The above picture shows the various sheets of ¾” MDF (medium density fiber board), that is glued and clamped together.

After the clamps are removed and the excess glue is sanded from the sides of the block, a layout is drawn on the top surface of the pattern. The next step is to cut the angles so that we can proceed along the lines of building up the pattern. Since a fiberglass mold will be pulled off this pattern, a two-degree angle is machined on all sides so the part can be easily removed from the finished fiberglass mold. If the two-degree draft is not cut on the sides of the pattern, the fiberglass mold will lock on and the two can never be separated.

After the clamps are removed and the excess glue is sanded from the sides of the block, a layout is drawn on the top surface of the pattern. The next step is to cut the angles so that we can proceed along the lines of building up the pattern. Since a fiberglass mold will be pulled off this pattern, a two-degree angle is machined on all sides so the part can be easily removed from the finished fiberglass mold. If the two-degree draft is not cut on the sides of the pattern, the fiberglass mold will lock on and the two can never be separated.

Shown above is one of the three blocks machined out to replicate the size and shape of the three arm pods. Two-degree draft is being sanded on all of the surfaces to ensure that the final pattern can be demolded from the fiberglass mold.

Shown above is one of the three blocks machined out to replicate the size and shape of the three arm pods. Two-degree draft is being sanded on all of the surfaces to ensure that the final pattern can be demolded from the fiberglass mold.

Pictured above is the overall design of the table plinth with the 3 arm pods correctly positioned before being glued together. The arm pods, as you may be able to tell, have also been cut with two-degree draft on all sides.

Pictured above is the overall design of the table plinth with the 3 arm pods correctly positioned before being glued together. The arm pods, as you may be able to tell, have also been cut with two-degree draft on all sides.

This photograph shows the application of a thin sheet of slate textured formica on alternating edge surfaces of the three arm pods and center pattern section. This is being applied just for aesthetic reasons so that the final part does not have an antiseptic, industrial look to it.

This photograph shows the application of a thin sheet of slate textured formica on alternating edge surfaces of the three arm pods and center pattern section. This is being applied just for aesthetic reasons so that the final part does not have an antiseptic, industrial look to it.

Here we see the three tone arm pods being glued to the center section of the pattern.

Here we see the three tone arm pods being glued to the center section of the pattern.

This shows the finished pattern temporarily bonded to a glass plate. Then clay is put in the joint between the glass plate and the pattern with a 1/64” radius. This will prevent the epoxy gel coat from seeping under the pattern. A production mold can now be made from this pattern.

This shows the finished pattern temporarily bonded to a glass plate. Then clay is put in the joint between the glass plate and the pattern with a 1/64” radius. This will prevent the epoxy gel coat from seeping under the pattern. A production mold can now be made from this pattern.

Before the pattern can be sprayed with a grey surface coat, it must be coated with a mold release agent so that the two pieces can be separated when the lamination is completed. Here we see a polyester gel coat being sprayed to all surfaces of the pattern.

Before the pattern can be sprayed with a grey surface coat, it must be coated with a mold release agent so that the two pieces can be separated when the lamination is completed. Here we see a polyester gel coat being sprayed to all surfaces of the pattern.

You will notice dark areas around the edges and corners of the part being laminated. This is a mixture of polyester resin, cotton flock, and glass beads to form a paste that is brushed on all of the rough surfaces, inside and outside edges, and corners of the pattern. This is applied in order to prevent air bubbles from being formed in these areas during the first lamination of fiberglass, which you see depicted in this picture.

You will notice dark areas around the edges and corners of the part being laminated. This is a mixture of polyester resin, cotton flock, and glass beads to form a paste that is brushed on all of the rough surfaces, inside and outside edges, and corners of the pattern. This is applied in order to prevent air bubbles from being formed in these areas during the first lamination of fiberglass, which you see depicted in this picture.

In a few days, multiple layers of fiberglass and resin have been applied over the pattern to a thickness of approximately 3/16” of an inch. This becomes the performance surface of the final mold. In order to rigidize and stabilize all of the fiberglass surfaces that have been applied to the pattern, we will bond ¾” MDF pieces to all surfaces.

In a few days, multiple layers of fiberglass and resin have been applied over the pattern to a thickness of approximately 3/16” of an inch. This becomes the performance surface of the final mold. In order to rigidize and stabilize all of the fiberglass surfaces that have been applied to the pattern, we will bond ¾” MDF pieces to all surfaces.

The final step in finishing the production mold is to apply a box that is bonded with a polyester paste to the wooden reinforcement pieces that were applied to the 3/16” thick fiberglass laminate. The mold is now completed and the molding will be the next step.

The final step in finishing the production mold is to apply a box that is bonded with a polyester paste to the wooden reinforcement pieces that were applied to the 3/16” thick fiberglass laminate. The mold is now completed and the molding will be the next step.

Here we see the pattern around which the production mold has been laminated. The glass plate has been removed and we are now ready to separate the pattern from the production mold.

Here we see the pattern around which the production mold has been laminated. The glass plate has been removed and we are now ready to separate the pattern from the production mold.

Here we see the production mold after the pattern (light grey color) has been removed. The production mold (dark color) will now be sanded, polished, and prepared to laminate the plinth for the turntable.

Here we see the production mold after the pattern (light grey color) has been removed. The production mold (dark color) will now be sanded, polished, and prepared to laminate the plinth for the turntable.

Above you see the picture of the fiberglass part that has been laminated off the prepared master mold in the previous picture. It was laminated with the same fiberglass materials as was the production mold, but to a laminate thickness of ¼”. It was then trimmed out, polished, and placed on the board you see above so that it can be used to produce a replica shape of what will be machined from solid aluminum.

Above you see the picture of the fiberglass part that has been laminated off the prepared master mold in the previous picture. It was laminated with the same fiberglass materials as was the production mold, but to a laminate thickness of ¼”. It was then trimmed out, polished, and placed on the board you see above so that it can be used to produce a replica shape of what will be machined from solid aluminum.

The MDF sub-plate you see pictured above will be sent to a machinist who will duplicate this part 1 ½” thick type 6061 aircraft aluminum.

The MDF sub-plate you see pictured above will be sent to a machinist who will duplicate this part 1 ½” thick type 6061 aircraft aluminum.

The Quintessence preamp on display at Listen Up, back in the day---far left, under the Phase Linear amp.

The Quintessence preamp on display at Listen Up, back in the day---far left, under the Phase Linear amp. This brief feature in High Fidelity, also from 1973, provided more details:

This brief feature in High Fidelity, also from 1973, provided more details:

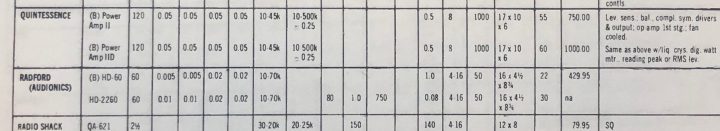

The 1973 Buyer's Guide of Audio provided full details of the Preamp, Equalizer, and Power Amplifier (in two variants). By the way---while the Quintessence preamp was $329.50, the Audio Research SP-3 was $595.00.

The 1973 Buyer's Guide of Audio provided full details of the Preamp, Equalizer, and Power Amplifier (in two variants). By the way---while the Quintessence preamp was $329.50, the Audio Research SP-3 was $595.00.

By the time those products were listed in the 1975 Buyer's Guide, the Preamplifier was priced at $500, at the same time that the Levinson JC-2 was $1050.00. 1975 ads in Audio described the Power Amplifier and Equalizer in unusual detail:

By the time those products were listed in the 1975 Buyer's Guide, the Preamplifier was priced at $500, at the same time that the Levinson JC-2 was $1050.00. 1975 ads in Audio described the Power Amplifier and Equalizer in unusual detail: