Musings from a long-time listener upon entering the hi-fi industry

I remember the exact moment the switch flipped. I was in my early twenties when I hit “play” and was blown away by what a couple of bicycle inner tubes and heavy books could do to the sound of my Sony CD-player and Indian-made Cox integrated amplifier. Since then, my love for music has been matched—and, if I’m not careful, exceeded by—a love for the products and optimizations that replay that music.

When I found a job in the high-end industry at 43, I had entered late but had the tools to be an ideal observer. I knew the language, but didn’t know the water-cooler gossip. I had the framework, but carried little baggage. In my first months, I asked every industry rep I met the same question. “Who’s the new audiophile?”

To my surprise, the answer was always some form of “I don’t know”, with the follow-up: “This industry has done a terrible job of promoting and branding itself.”

“This is over,” said more than one rep (usually the younger ones) pointing at racks filled with audio equipment, bristling with cables, and flanked by looming speakers. “Nobody wants this any more. It’s all about convenience.” [Smartphone waggled for emphasis.]

The death of high-end audio… again?

But is that true? It’s true this year certainly. Much has been made of how the millennial would rather hike to Choquequirao than buy a power amplifier. That audiophiles are (literally, given their average age) a dying breed.

Many audio companies have decided that democratization is the way forward. All-in-one products with slick smart phone and tablet apps, streaming technologies, and lifestyle design. These boxes have few cables, offer easy set-up, and equally democratic usage by fitting near-invisibly into homes with children and non-enthusiast domestic partners. (“What do you mean, power-up procedures? I just want to play my damn music!”)

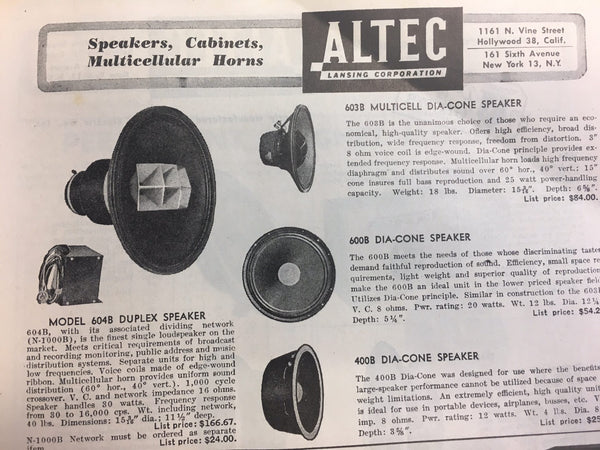

So what hope then for the rack of audio equipment and giant loudspeakers? I believe that the death of retail as we know it offers an answer. In the news of the end of malls, and the closing of national retail brands, is the hope that the future of retail isn’t only online, but in a specialized marketplace of spaces that offer “experiences”, especially if those are hand-made, curated, and highly personalized.

Here’s the thing: the high-end audio store has always been this kind of experience. It has always been about dedicated listening rooms, beautiful products, and a need to understand who the customer is, before selling to them. It has always been about knowledgeable curation, expert-led “auditions”, and a generous take-it-home-and-try-it policy. With its polished metal, glowing vacuum tubes, and incremental upgrades it has always been Instagram gold, the consistent “braggable” experience. And finally, it has always been about education and open-mindedness: technical seminars, listening events, and a high level of customer access to the people who actually design and build the products.

And yet, this is an industry that is seen in general as snobbish, elitist, and only for people with more money than sense. And that’s if it’s seen at all. I recently showed my mother (a well-read, tech-savvy theater professional) a photograph of a brand new Audio Research VT80 power amp. “Is that an antique?” she asked. “I remember vacuum tubes from when I was young!”

And this, according to nearly everyone I speak to, is the industry’s own damn fault. Shouldn’t it then be actively moving the discussion to a more formal venue than the editorial pages of consumer audio magazines, and hotel bars at audio shows? Is offering interchangeable speaker grilles to match decor, and color options from the RAL swatch book part of the solution… or the problem?

But real things matter!

David Sax, in his book The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter (PublicAffairs, 2016), writes about how we’ve fallen in love again with supposedly outdated technologies, many of them messy and difficult, but all of them somehow real. The first chapter is “The Revenge of Vinyl”, and whatever your views on the purported revival, I’m sure you’ll agree that there’s at least the hint that the long-term future of high-end audio might lie, not in its convenience, but its obduracy. If you’re a photographer, the parallel would be the astonishingly healthy market for film photography.

But obduracy must be marketed with care. At its least empathetic, aspirational branding focuses on the product, telling the customer that it is better than they are; that they need to prove their credentials. This may have worked for luxury audio in the past, but absolutely will not work in this millennial era, in which anybody of any age who uses a smartphone has a little millennial in them.

After all, when millennials are described to and by marketers, they sound startlingly like audiophiles. Even with the “experiences, not ownership” concept mentioned earlier. Sure, audiophilia involves a lot of product ownership, but audiophiles revel in how it offers experiences—moving experiences—at the push of a button.

Millennials are said to value authenticity. Okay, let’s never forget that the term “high-fidelity” promises truth, not quality. (“If the original is bad, we’ll make sure the playback sounds just as bad!”) Short signal paths, naked power tubes, exposed heatsinks, no unnecessary features… these are all signs of brute honesty.

Millennials are apparently not swayed by regular advertising, and don’t find brands through conventional channels, instead seeking like-minded users or experts of their choosing. Surely that is every audiophile who has breathed and logged on to an audio forum or attended a show.

Millennials use technology to the fullest. In response, I present the audiophile who loves to pretend to be a Luddite even as he knows precisely where and how his MQA files are unfurled for his delectation over streamer, server, DAC, and dale.

And finally, millennials want to be acknowledged, and never talked down to. This is the industry’s cue to shift the traditional product focus of aspirational branding to the customer, and tell him or her that there exist products of such sophistication and subtlety, that they are humanistic. The customer doesn’t need to prove credentials, being human is complex enough. It’s the product that has to match up to the level of high discernment that’s now the norm.

All this suggests to me that when, and if, the industry does emerge from invisibility (and by all accounts, that needs to be soon), it should do so with full acceptance of what it is: narcissistic, eccentric, precious, and obsessive, yes. But also capable of leading us into beauty in a deeply human way like few other luxury products can consistently do. Even if the source is digital, the multi-box, multi-cable, multi-shelf system is hopelessly, romantically analog in the way it can be nurtured and optimized, ever towards, but never attaining, perfection.

Democratizing the high-end audio experience requires changing the very fabric of its universe. Consider instead that its traditional perception problems of elitism and unnecessary complexity are across a thin line from deep customization and analog uniqueness. All that’s needed is the flip of a switch.