Loading...

Issue 128

Things Change With Time

Ballroom Blitz

How was your New Year’s Eve? New Year’s Eve, ring a bell? Someday this pandemic will end and we will return to celebrating the end of the old year and the birth of the new in the company of total strangers. To quote Prince: “dance, music, sex, romance.”

It’s my theory that my demographic cohort, the Baby Boomers, will be the last generation to plan ahead, dress up, pay an enormous sum for a passable meal, and dance to rock and roll or something close to it. Don’t count on the Gen Xers to take this baton. My people: we can’t afford to lose a year! We’re aging, our knees are degrading, we can’t stay up as late as we used to, and we’re definitely popping two ibuprofen with breakfast. It takes a nation of millions to pay for our health care.

I remember in the late 1980s when the Gen Xers figured out that the Boomers were sucking up all the oxygen on the planet. “It’s a hard world to get a break in/all the good things/have been taken,” the Animals sang. Back then, I had several discussions with these tiresome young people. They complained to me, with their imperfect command of their native language, that, like, you Boomers were always stealing the spotlight and like grabbing everything for yourselves, dudes, and what’s up with that? I always listened politely and then reminded them that we are really good-looking, too.

Dudes. Do you want to be in that number when the Boomers go marching in? Let’s not forget what to do on New Year’s Eve! What follows are a few thoughts on clothes and music from past New Year’s, based on 40+ years of counting down to midnight and raising glasses of cheap champagne at taverns, clubs, discos, restaurants, banquet halls, charity balls, and, once, a rave*.

* A note from AARP: Raves are not for older people. No one has ever gotten to the end of the line for the bathroom at a rave.

Clothes Make the Man

I don’t have to tell women to assemble a special outfit, as women understand that New Year’s is an occasion and an occasion is something you rise to. It’s men I’m speaking to. Don’t wear what you normally wear to the office, and definitely don’t wear what you wear to a Zoom call, since I’m guessing you don’t wear pants to a Zoom call. Go shopping, even if it’s in your own closet, and don’t go without your partner. Other people can look at you, shudder, and move on, but your partner will have to look at you all evening. Have mercy.

The best look for men is a snappy suit, but if you can swing it, get fitted for a tuxedo. Bonus points: a tuxedo with a swallow-tail jacket or with a vest. Any idiot can grind on the dance floor, but how many can pull that off from inside a tux? Master that skill and you will never lack for someone to dance with.

Once you’ve been cleared by the style council, grab your keys. It’s clobberin’ time.

Play That Funky Music

I don’t play an instrument. I type. So it is with some hesitation, but much respect, that I offer the following suggestions to the groups of nice old guys who usually end up playing for us on New Year’s Eve. You guys rock, whether you’re wearing black T-shirts, black button-down shirts, or something Hawaiian, and I love how you always massacre at least one oldie, then turn around and surprise us with a head-banging dance tune with an off-the-hook keyboard solo.

I’m just glad you’re not the band that played one of our events a few years ago. Everyone in that band was 25. They neutered everything, perhaps out of concern for our blood pressure. “Sweet Home Alabama” was about the weather. “Mustang Sally” was about a horse. The singer kept complimenting us on how beautiful we were. I think she was surprised that we were still alive.

Here goes:

- Time your last set so you end about three minutes before midnight, which gives everyone a chance to freshen their drinks and get ready for the countdown. This should be obvious, but we heard a band on New Year’s Eve that stumbled to a stop 10 minutes early. After some onstage consultation, they tried to stall with “Free Bird,” which caused half the crowd to whip out their lighters and the other half their fingers. They would’ve been safer with “Love Shack.” When they finally escaped into “Auld Lang Syne,” it was obvious they hadn’t practiced it.

- Please practice.

- Your audience will begin to evaporate at one minute after midnight. Maybe they want to finish the evening in their bathrobes eating ice cream; maybe they want to get romantic at home rather than against one of your speakers. It’s not about you. You’re awesome.

- We’re all trying to be woke today, so avoid songs celebrating relationships with underage girls: “Well she was just 17/you know what I mean,” “You’re 16, you’re beautiful, and your mine,” “Hey little girl won’t you meet me at the schoolyard gate,” “But you’re so young and we can’t go on this way,” and I’m concerned that I knew these four off the top of my head.

- Between sets, the venue’s PA system will play watery hip-hop for people to do the line dancing they learned at corporate retreats in the 1990s. That’s not your problem, that’s ours. Enjoy your beer.

There’s Got to Be a Morning After

New Year’s resolutions are a minefield. How do you make a resolution and stick to it? How do you make a resolution and remember it two days later? There are two secrets to successful resolutions.

This is the wrong way to resolve to start a band: “I will start a band, make a ton of money, and meet a ton of chicks.” But this might work: “Step One: I will decide what kind of music I want to play. Step Two: I will jam with some like-minded musicians.”

If on January 31 all you have to show for your efforts is a dislike for Coldplay and a bass player who keeps forgetting to come to band practice, you will still be ahead of where you were on January 1 and much happier than the people who gave up on January 15.

You’re welcome. My people: Let’s try this all again on December 31, 2021. Happy belated New Year’s!

Header image courtesy of Gerd Altmann/Pixabay.

The Stranglers Come Stateside

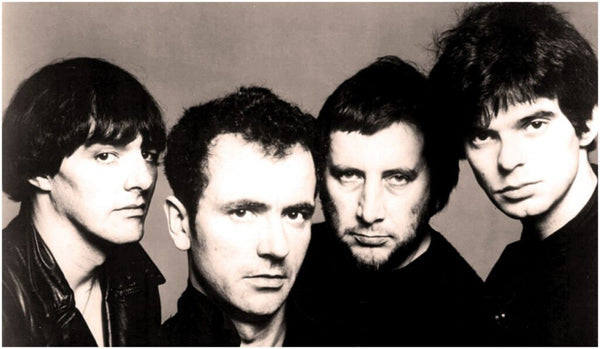

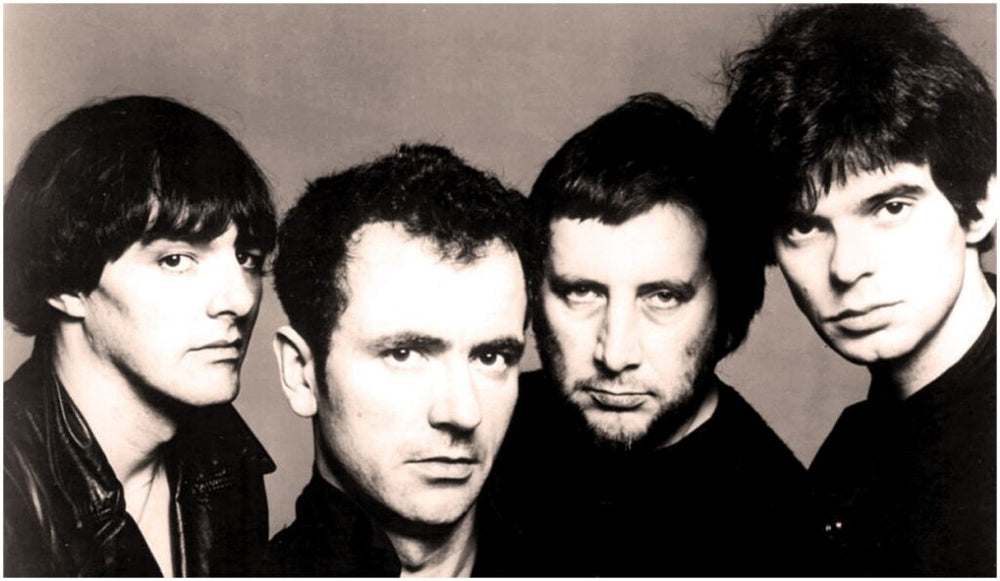

I met them as they came off the plane at JFK in New York. About three weeks after the Stranglers’ UK 1981 tour ended (see my article in Issue 111) the American tour was scheduled to begin. The Stranglers are one of the more successful British punk rock/new wave bands of the era and had success with singles like “Something Better Change,” “No More Heroes,” “Always the Sun” and others.)

We all taxied into town and I checked them into Manhattan’s Abbey Victoria Hotel at 51st Street and Seventh Avenue. The next day they started rehearsals at SIR (Studio Instrument Rentals, the number-one spot for equipment rentals and a facility with well-equipped rehearsal rooms. SIR was all the way on the West Side of Manhattan, in a tremendous prewar industrial manufacturing building that in the days of old had railroad access. You can still see the tracks. They occupied three or four floors, which was a lot of space. There were more than a few rehearsal rooms of varying sizes, and a couple of showcase rooms where a band could play to guests like the group’s record company or booking agency.

I was familiar with SIR and had used it for other groups at various times. I once was invited to see Steely Dan’s last rehearsal before they began their tour. It was in the early 2000s, some time after their long hiatus, and the band did their set with no breaks, just like in concert. Those showcase rooms were a great place to simulate a concert. In some cases, (not that often) the rooms could also be used as audition spaces. SIR had really worked out the acoustics and besides, you would never know who you would bump into there. Many artists did pre-tour rehearsals at SIR.

The Stranglers. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Stranglers France Service.

The Stranglers. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Stranglers France Service.

In the Stranglers’ case it was not so much for rehearsing their material but to test the keyboards and amplifiers. This is a smart way for British bands to tour the States because for one, there is a different electrical current here (120 volts, 60 Hz) than in Europe (220 – 240V, 50 or 60 Hz). Bringing your own amps and keys could be problematic, even with the use of voltage-conversion transformers, causing buzzes and pops – or worse.

Also, there is the consideration of theft – the Stranglers had their equipment stolen during their previous American tour in 1980. Every band that uses a box truck has their equipment robbed at some time or another, and rental equipment is easily replaced. The Stranglers came into the country with just guitars and drums. The band and crew had to test and get used to the equipment they’d be playing for the US tour, and the best way to do that was by trying it out. They spent a few days familiarizing themselves with the new equipment.

First gig was a three-day affair at the Lexington Arts Center, a ballroom in a building located at 150 East 85th Street on the corner of Lexington Avenue. When it was used for concerts it was called Privates. The opening act was the Bee Girls, and the Stranglers went on at 12:30 in the morning. A very New York scene.

On Monday we drove to Allentown, Pennsylvania in two rental cars for a show at Nico’s. It was a small club with a capacity of 300, no booze or food, just beer. The boys were not thrilled about this date. It was obvious that we were not in New York anymore. This was an uneventful and forgettable night.

Next day we had to drive east to Providence, Rhode Island. On the way I stopped in Jersey City at Hertz to swap out one of our rental cars. We had been saddled with a year-old rental with 23,000 miles on it. For rental cars this was already an old heap; thusly, I did a vehicle exchange. The club in Providence was the Center Stage, and it was a proper rock club with a capacity of 800, much more in line with the band’s stature.

Wednesday, we had a short drive to Boston to play The Channel, which was an iconic rock venue then known as Boston’s largest dance and concert club. A who’s who of bands played there in its heyday. It was located right on the Fort Point Channel in a notoriously famous area that was just a couple of hundred yards from where the Boston Tea Party happened. The Fort Point Channel had a colorful history of skullduggery. The show was a good one, totally rocking, and when the last song was finished, we went through the backstage area to our dressing room. Escorting us from the rear was a club security guard who was a really big man. When we got into our dressing room Jet Black, the Stranglers’ drummer, slammed the door closed and I guess the security guard thought the door was purposely slammed in his face.

Next thing we know, he starts to kick the door in. We’re all looking at each other and on the second kick he splinters the door, sending wood flying every which way. He yells at us, “who the hell do you think you are?” and takes a step into the dressing room. WTF, we are thinking, and at that moment a couple of other security guards show up and grab him. They are all his friends, but they know that what he’s doing is not cool, so they calm him down and take him away. The club’s manager rushes in and profusely apologizes, and he quickly has his crew put up a big piece of plywood as a makeshift dressing room door. The evening’s drama (and our contribution to the area’s colorful history) was over.

The Shaboo Inn in Willimantic, Connecticut was a relatively short drive east, maybe 100 miles from Boston. It was another rock club, with a funky smell of stale beer and sawdust on the floor. The stage was small, low and close to the ground.

J.J. Burnel, the bass player, was upset about the date. The club was grungy, but more importantly, the stage was too low, which made for easy audience access. Sometimes unruly audience members would jump on stage. In fact, before going on Jet and J.J. had discussed if they should cancel the gig for safety reasons (their own). As it turned out, it was a good night and a good audience, nice people.

However, this third car that I had rented from Hertz was also crap. I called Hertz and told them I wanted to switch it out on Saturday, when we would be back in the New York City area. This tour was going to be all driving – no tour buses or planes. I needed a good car. As nicely as I could, I told the people at Hertz if they couldn’t get me a decent car I would go to Avis. I was a particularly good customer from all my years on the road and literally hundreds of Hertz rentals. They assured me they would find a car that would make me happy.

It is Friday and we are playing the Left Bank in Mount Vernon, New York. It was one of the area’s more well-known rock clubs with a lot of history and a good reputation. At the time they were booking a lot of New Wave and punk acts. They really had their act together, even providing some humpers to help with the load in and the load out. In other clubs a band’s road crew was pretty much on their own with unpacking, set up and load in. There was usually a stage manager around to answer questions and point things out involving the lights, electricity and such, but for the most part our crew did the humping.

The opening act is Single Bullet Theory and the Stranglers are due on stage at 1:30 am. This is normal for East Coast clubs, because they wanted the patrons to stay late and make as much money from the bar as possible.

Ed Kleinman, the Stranglers’ manager, was coming up from the city with a bunch of guests, so this was going to be an important show. The band delivered, like they usually did. The Stranglers never had an off night, but there were times when the energy was really focused and the show had a special feeling. Afterwards we all drove back to the city because the next night we had a gig at Irving Plaza. I stayed at home that night because I lived two blocks from Irving Plaza. The band and crew stayed at the Abbey Victoria again.

Saturday night in New York City. This is going to be fun. The Irving Plaza show is an important one because a lot of press people are going to be attending. The guest list was big, including my wife and three of our friends.

The Stranglers did not disappoint. Irving Plaza was more like the venues they played in the UK and they were in a good mood and ready. They absolutely, totally kicked butt and did a longer set than usual that ended way after 2:00 am. Afterwards about 20 of us went to an after-hours club to party. The next day the band had the day off but I had to go back to Hertz on West 56th Street to swap out the rental car.

When I got there that afternoon, they were ready for me with a brown 1981 Oldsmobile Delta 88, brand new, with a scant 66 miles on the odometer. “Well, alrighty!” I said and there were smiles all around. In fact, in all my years as a road manager this was one of the nicest cars I ever rented.

Unlike the previous UK tour where my passengers were Jet Black and keyboard player Dave Greenfield, on the American tour I was driving guitarist/vocalist Hugh Cornwell and bassist/vocalist J.J. In hindsight this was my mistake. Jet and Dave were always a few minutes ahead of us and that meant that Jet would get to the gig or the hotel a few minutes before me and had to wait for me to fix any problems or issues. Not an ideal situation. We didn’t drive in a caravan; we just left roughly around the same time. We always had two rental cars on every tour, with J.J. and Hugh in one and Jet and Dave in the other.

Dave Greenfield and Ken Sander.

Dave Greenfield and Ken Sander.

When I picked Hugh and J.J. up at the hotel Monday morning they were really pleased with the new Delta 88.

On this tour we spent every night in motels like Holiday Inns and Ramada Inns, decent enough, three stars. The only exception was after the gig we did in New Orleans when we left right after the show for Houston. If we got hungry while driving, we stopped on the road to eat. Sometimes were would eat at the gig but it was pretty much a decision made in the moment.

Then off we went to Toad’s Place in New Haven, CT (yet another famous East Coast club and still open today, though temporarily closed for the pandemic). It was a Monday show and we went on stage at 11 pm, an early night for us.

Now we are really starting to log some miles as we go to Orange, New Jersey, Virginia Beach, Washington DC and Cherry Hill, N.J. Sunday we had a day off and we all decided to drive back up to NYC. Monday morning we leave for Cincinnati and that night on the way there I get pulled over for speeding. The Ohio state trooper asks me to come and sit in his cruiser, leaving Hugh and J.J. back in the car. He writes me a speeding ticket. Then he asks if I have an American Express card, to which I answer yes. He says, “well, you can pay the ticket now with your Amex card.” Really? I give him the card and he swipes it. “OK,” he says, “we’re good; you can go.” I asked, “what if I didn’t have an Amex card?” He answered, “then I would have to take you downtown to the station.” Really? Yup.

After playing Bogart’s in Cincinnati (temporarily closed but still there today) we drive to Athens, Georgia to play Tyrone’s, with an on-stage time of 10:00 pm, a respectable hour for rock and roll. Next day we had a short drive to Atlanta for Friday and Saturday night we’re playing at the 688 Club. Sunday is a travel day, and we drive 500 miles straight through to New Orleans. Monday after the gig we drive all night, 365 miles, to Houston, Texas to play the Agora Ballroom with a 10:30 pm onstage time. The on stage start times have been getting earlier since we left the Northeast.

We catch up on sleep by negotiating a later check-out time with the hotel and leaving later the next day for Austin, Texas, 162 miles away. We are playing Club Foot and it is a lively scene. Austin is a way cool city with a cosmopolitan vibe. They knew who the Stranglers were and showed their appreciation. After the show we were taken out and the night life was really happening.

Next morning we continue to Dallas (the Club Bijou) and the next day we drive to Lawrence, Kansas, (the Opry House), before heading 585 miles west to Boulder, Colorado for two nights at the Blue Note. We were told that the Blue Note was owned by Genya Ravan of horn-driven rock band Ten Wheel Drive. She was not there those nights, so this was unconfirmed. (Do any readers have any information about this?)

Getting up early Thursday morning to get a start on the next lap, we have till Friday to get to Los Angeles, 1,180 miles. We drive all day into the night. I tell the guys that it would be cool to stop over and stay in Babylon, er, Las Vegas, and they agree. It is close to midnight and we are still about an hour out when we first see the lights of Vegas. It is an amazing sight, even considering this was back in 1981. Today Las Vegas is easily 10 times bigger. The closer we get the bigger the lights are. We check into the Stardust and they put us in the back in motel-style outdoor rooms.

The bellhop assures us: anything we want, legal or not, just ask him and we will have it in under an hour. This was still the anything-goes wild days of Las Vegas; unlike today where it is more corporate.

Friday, we play Pasadena’s Perkins Palace. Saturday it’s the Reseda Country Club on Sunday we hit the Bacchanal in San Diego before driving back to Los Angeles.

On Monday when I go to the car, I have an unpleasant surprise. The front passenger side door is bashed in and will not open. I have to exchange the car with Hertz. But we got 6,000 miles out of this one, not bad for 10 days driving.

The tour went on to play many of the same dates as Split Enz had done when I was their road manager (see Issue 124 and Issue 125), except the Enz flew. The Stranglers headed north to Vancouver, then south to Duluth and back east and up again to Canada.

I think it is safe to say the Stranglers were not thrilled with the tour.

It was hard work and they had to play some crummy venues. They are a bigger act in the rest of the world, so this tour with its smaller venues was somewhat of a comedown for them. But give ’em credit – there was no whining from them in their untiring efforts to conquer the American frontier.

The band in 1981:

Jet Black, drummer and founder – retired

Hugh Cornwell, lead vocals and guitar – left the Stranglers in 1990 for a solo career

Dave Greenfield, keyboards – died in 2020 of COVID-19

J..J. Burnel, vocals and bass – the only original member still in the band. He currently lives in France.

Mic-Boggling: Sylvia Massy's Microphone Museum

Producer, engineer, author and educator – these are just some of the roles that can be attributed to Sylvia Massy. Her work with Rick Rubin, Tool, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Johnny Cash, Lenny Kravitz, Aerosmith, Queens of the Stone Age, Tom Petty, Prince, Seal, and many other artists could fill an entire music library.

In 2017, she and Chris Johnson wrote a successful book called Recording Unhinged, and the publisher requested a follow-up book on vintage microphones. In researching the book, they traveled around the world to find mics, document their stories and gather information from engineers, producers, artists, and studios. In Milwaukee, they met Bob Paquette, who owned the largest private microphone aggregation in the world, amassed over 67 years. Sadly, Paquette passed away before they could meet again, but Massy and Johnson purchased the collection from his estate, which will be a key element in creating the new book.

Humorously referring to her love of microphones and her mic museum collection as a “gear problem,” “Sylvia Massy’s Mind Blowing Microphone Museum!” was presented online as part of the Audio Engineering Society’s AES Show Fall 2020. No stranger to teaching, Massy has conducted numerous workshops for the Abbey Road Institute in London, as well as at Castle Röhrsdorf in Dresden, Les Studios de la Fabrique in France, and in other seminars in Rome, Oslo and other locations. She has a series on her YouTube channel called “Mic du Jour,” where she features mics from the museum.

The virtual presentation was conducted from her studio in Asheton, Oregon. Massy demonstrated the mics using Neve, Looptrotter and WEM consoles, Maag Audio equalizers, and preamps from Maag, Looptrotter and Warm Audio.

Carbon Microphones

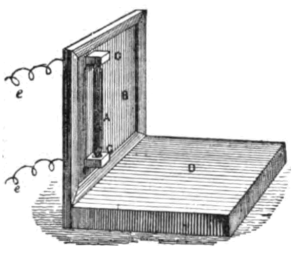

Above: a reproduction made in early 1900s): Starting from the beginning in 1876, the presentation showed a replica of the very first microphone, a liquid transmitter mic built by Alexander Graham Bell. Resembling a tall milkshake cup on a small stand, it operated by speaking into the cup, which vibrated a parchment diaphragm connected to a wire dangling in a small cup of acid. The fluctuations of the current moving through the acid is what created the audio signal. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Floyd L. Darrow.)

Above: an original carbon microphone made by David Edwin Hughes, it is a wooden hinged unit resembling a jewelry box with a bracelet on top. A pressed carbon “pencil” sits in the box. It operates by closing the box and speaking into the bracelet-shaped disc, which vibrates the pencil, which, in conjunction with a 6-volt battery charge, creates the audio signal. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Thomas Gray.)

Massy actually used the carbon microphone on a vocal session in Los Angeles and it still worked!

Not pictured: an improved carbon microphone. It featured a larger wooden box of similar design, mounted on a wooden pedestal, resembling some of the early telephone boxes seen in old photos (late 1800s) and silent movies. Granulated carbon packed into a tiny button would vibrate in the box to produce the signal.

Above: a metal double-button carbon microphone made by Western Electric, Model ET3, formerly used at radio stations. It has a metal base with a hoop loaded with an 8-spring shock mount ,centering a hockey puck-shaped disc that holds the diaphragm element touching a small button filled with carbon. Sound vibrates the diaphragm, which excites the carbon particles in the button that transmit the sound by changing the signal being sent to the microphone. The power requirement ranges from 6-12 volts. This design became very popular in the 1920s. Photos of movie stars like Gloria Swanson were taken with double-button microphones, which became the US industry standard for the era. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Daderot.)

Above: a candlestick microphone. Reminiscent of a tabletop telephone from the 1900-1920s period, it was made from polished brass by Western Electric. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Joe Haupt.)

The carbon mics are classified by Massy as “non-directional” as they are neither unidirectional nor omnidirectional.

Not pictured: an early European carbon microphone (1878) by Siemens and Holstein was called a “Butterstamp.” Used at the post office in Germany for transmitting over telegraph lines, it looks like a wooden candlestick with a wide top and a separate leather cover and leather-bound handle.

Not pictured: a German Reisz Type 104 coal microphone. (Europeans refer to carbon mics as “coal” mics.) It is shaped like a jewel box with a large but very thin layer of carbon particles that vibrate a rubber membrane diaphragm. The case is made from hollowed marble, making it quite heavy. These types of mics were used by Josef Stalin and the UK royal family, among others.

The Reisz microphone was actually developed by one of its young employees, George Neumann, while Eugen Reisz was on vacation.

Above: an improved Reisz type mic built by the Marconi laboratory in London. Marconi refined the design with an octagonal shape and smaller surface area. Massy found one in the EMI London archives with gold filigree ornamentation that had been built for the Queen Mother for her radio addresses. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Jan Kameníček, cropped to fit format.)

Massy compares Reisz mics to that of old telephones: limited fidelity but rugged. One of Massy’s music production tricks is to take the carbon mics from old thrift store telephones and wire them up in the studio for recording to get a unique, limited-frequency radio transmission sound.

Condenser Microphones

The condenser mic was invented by E.C. Wente at Westinghouse in 1920. It was the first mic to contain two charged plates with one of them acting as the diaphragm, while the signal was generated from the variance in signal between the moving and stationary plates.

Not pictured: a Neumann CMV-3 with a Telefunken badge. Massy originally thought this was the first high-end condenser mic. It has a long cylindrical tube with a ball end that has a grill on one side.

Not pictured: The Western Electric 394W. E.C. Wente beat Neumann to the market by a few years. The 394 has the appearance of a larger double-button carbon mic mounted onto a wooden box. The box holds the power supply, which contains transformers, wiring, and a large, round vacuum tube. This model was used by president Calvin Coolidge.

Not pictured: a Western Electric 7A. It is alternately nicknamed, “The Tombstone” or “The Mountain Clock.” It looks like a tombstone with a circle at the top inside the arch, which contains a 394 capsule. The base contains the power supply. This mic can be seen in photos in use by Winston Churchill.

Above: a 1928 Western Electric 47A. A long, thick cylinder with an angled grilled capsule, it was designed to hang inverted so that the heat from the power supply would rise and not affect the capsule. It is full of tubes and its design became very popular with amateur radio DIY stations. Hooking up her own power supply to it, Massy tested it, and the sound quality is significantly superior to that of the carbon mic.

Not pictured: a Western Electric 640AA. It is a long, chromed cannon shell-shaped mic with a flat 640AA capsule from the 1930s in a shock mount. It is smaller than earlier mics and closer to the size of a Neumann U47. The internal wiring showed advances in the miniaturization of components and the use of flatter and smaller 382A vacuum tubes.

Not pictured: an Altec 165 “lipstick” mic. This legendary mic is the US version of the Neumann KM53 and KM54 and has interchangeable capsules. Advances in technology, including the narrow size of the 5840 vacuum tube, enabled the smaller size of the mic. It remains an excellent and useful mic to this day.

Dynamic Microphones

Dynamic mics were first introduced in the early 1920s.

Not pictured: an early Round Sykes dynamic mic from Marconi Lab designed by Captain H. J. Round. It has a heavy magnet and looks like a theater light with six outer rim rivets and a central rivet holding a plate against a short, wide cylinder. This was the first dynamic mic in history and was excellent for field recording. It was used by King George V for outdoor speech recording to a magnetophone, the first tape recorder. The EMI archives photos show that the King’s Sykes mic had a silver filigree windscreen cover.

Above: a photo picturing multiple Western Electric 618A mics. A very popular mic in the 1930s, there are photos of Franklin Delano Roosevelt with all of the mics from the radio networks in the photos being this model. It looks like an Inky light on a U-mount yoke swivel. The Vitavox Admiralty mic was the UK version of the same design. The WE 618A design was even copied in Japan.

Not pictured: A Western Electric 630a “Ball and Biscuit.” It is shaped like an aperitif glass with a flat top. A very popular design, it was copied by STC (Standard Telephones and Cables Limited) in the UK, and by France and other nations.

It sounds very natural and Massy has used it in sessions as a room mic. It is still available in used markets from $200-$300.

Above: the beyerdynamic M19B led the way in European dynamic mics. Popular for radio and recording, it looks like a large acorn with a center post and is omnidirectional. (Courtesy of beyerdynamic.)

Above: the classic Shure 55 Series – the “Elvis” mic. Popular with singers, including Presley and Billie Holiday, it debuted in 1939. It is still in production and is the preferred mic of Metallica’s James Hetfield (above, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Pingaiadadocrack).

Above: an Electro-Voice 630. Featuring a small chrome body on a hinged post, this model is still available and good to use for recording.

Above: a Shure SM57. This is Massy’s favorite mic. She owns the one that David Bowie used for the Tin Machine albums (which was borrowed from her personal collection). This mic and the SM58 vocal mic are industry standards on stages and studios worldwide, and have been for a long time.

Ribbon Microphones

Not pictured: The first known ribbon mic was the Siemens ELM25 (1925). It looks like an old box camera on a yoke. It is a directional ribbon mic with a replaceable cartridge. It was used by Joseph Stalin. The mic did not need a power supply. The velocity of the sound vibrated the ribbon and the strong magnets generated the signal voltage.

Not pictured: the RCA77A. This large, bulky mic was designed by audio pioneer Harry Olsen. RCA started using ribbon microphones in broadcasting for their high fidelity and because they didn’t need power supplies. The first-ever RCA microphone was the PB17. The RCA 44 (shown above) and others soon followed. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/LuckyLouie.)

Above: a production model RCA 77DX. It's become an iconic and familiar sight. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Scott Bomar/Jacob Blickenstaff.) Demonstrating the RCA 44 prototype, Massy showed it was a rich, very warm-sounding mic.

Crystal Microphones

Crystal mics operate on the principle that crystals emit a charge when bent, so a very thin slice of crystal is attached to a diaphragm by a pin. The vibrating diaphragm creates an electrical signal in the moving crystal. Piezoelectric mic development was pioneered by the Brush family. Not pictured: a Brush BR2S resembles a small Shure SM58 and is omnidirectional.

Above: the Astatic company formed in 1933 and licensed crystal mic technology. They made a hugely popular chrome lollipop-shaped mic: the D104, in production from the 1930s to the 1990s. Since 2000, Astatic is now part of CAD Audio. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/LuckyLouie.)

The Turner 44X, which looks like a sci-fi robot helmet. The Heil Sound "The Fin" mic shown above is a modern re-creation. Other crystal mics in the collection included the rocket-ship-shaped Astatic 600S, a Massy favorite, and the Turner 80X, which Massy for its different sonic character, akin to a walkie talkie. Crystal mics are not known for their high fidelity but more for use in communications. The inherent problem with these mics is that the crystals are often salt-based and rapidly deteriorate when exposed to humidity. Sylvia Massy’s microphone collection is a fascinating look as to how the technology has evolved over the last 150 years.

For more perspective on its immensity, visit https://www.sylviamassy.com.

To Test or Not to Test, That is the Question, Part Four

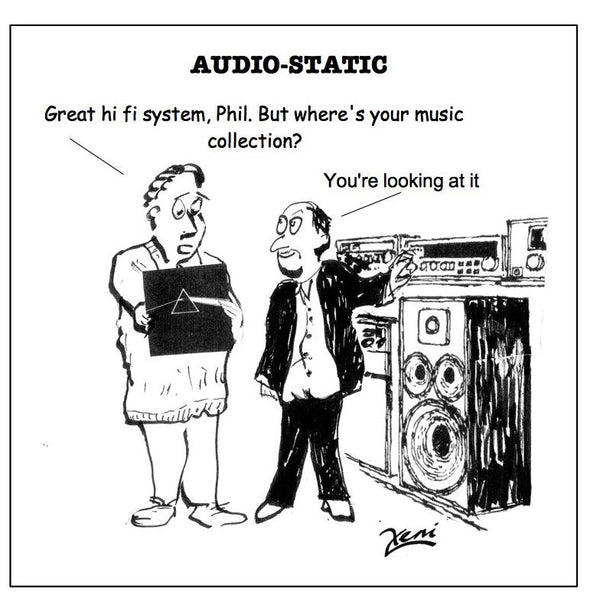

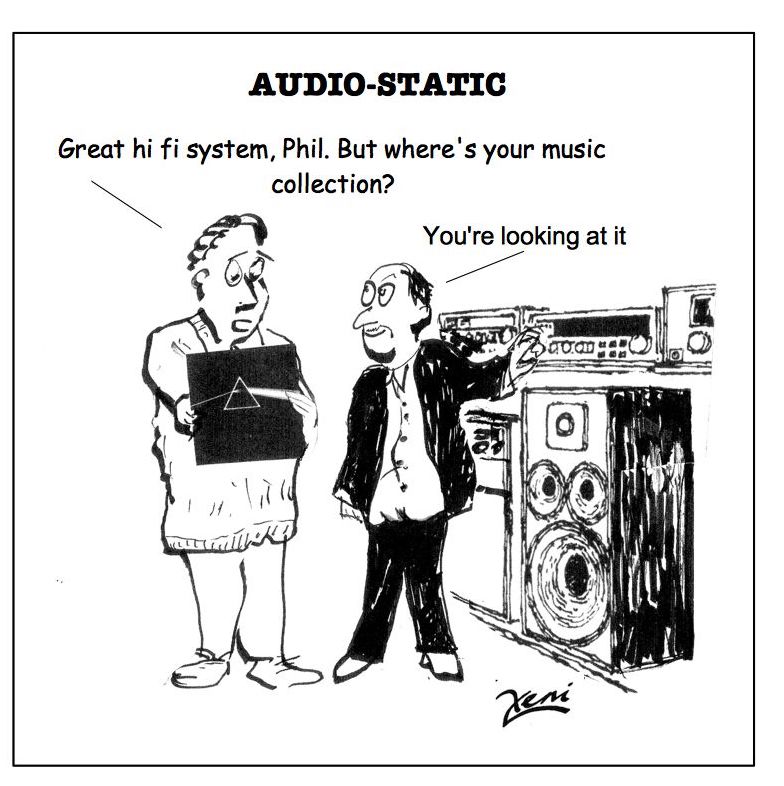

In the last two installments of this series, I discussed measurements of the two components most prone to developing or causing problems, namely our ears, and room acoustics. The rest of the components in an audio system are perhaps less problematic, but no less worthy of attention.

There is little point in measuring commercial electronic equipment (amplifiers, preamplifiers, digital players and so on) unless you are a reviewer or if you are one of those people who believe that commercial hi-fi equipment is always suboptimal, and it is always possible to squeeze additional performance out of it (i.e. doing “mods”). Some people have a firm belief that only boutique internal components (like capacitors and resistors) could ever sound good, and proceed to rip out all the standard parts and replace them with boutique parts that are ten or even a hundred-fold more expensive. However, while it is true that manufacturers have to take into consideration the cost of production (except for a handful of products targeting multi-millionaires), the specific internal components in a product are often chosen by the designers to achieve a particular sonic result. Changing to something more expensive might change the characteristics of the sound, but is it necessarily for the better? The designers might have tried dozens of alternatives to arrive at their final choice. Would audiophiles do the same, or do they rely on hearsay to decide what to install?

That said, upgrading transistors and op-amps might actually yield some benefits, as the performance of these components has been improving all the time. Op-amps tend to have a bad reputation amongst audiophiles, who might be horrified to learn that the microphone preamps, recorders, mixing desks, compressors, limiters and other professional audio equipment that were used to record their cherished LPs and digital music were most likely chock full of them. Modern op-amps are far quieter, have lower distortion and higher slew rates than the best examples from 20 years ago. However, before you go and swap them all for AD797s (one of the highest-performance audio op-amps currently available), beware that the op-amp could end up oscillating, and modifications to the feedback network might be needed to make sure that does not happen.

Another worthwhile endeavor is to ensure that the transistors are matched in differential circuits and in output stages that utilize parallel devices. An advanced semiconductor analyzer such as the PEAK Atlas DCA75 Pro costs less than $100. Transistors are inexpensive items; buy a whole bunch of them and match them up in pairs and quads. Matching the DC current gain (hFE) is important in differential circuits. The DCA75 Pro measures the hFE at a constant collector current. Beware, however, that the measurement is temperature-sensitive, and holding the transistor between your fingers while doing the test could change the measurement. Also, match both the hFE and the VBE (base-emitter voltage) for parallel output devices, otherwise one device will always conduct more than the other, shortening its life. A friend recently decided to revamp his Bryston power amplifier, and after removing all the output transistors, he found out that they were very poorly matched. Whether they became mismatched over time or started life this way is unknown.

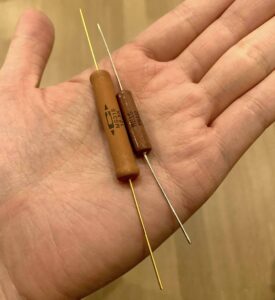

As for passive components, most high-quality thin film resistors have performance characteristics that are very close to perfect at audio frequencies. In situations such as phono stages, it would be worth using high-performance resistors such as bulk metal foil precision resistors. These are much more stable and have tighter tolerances, lower noise and faster rise times than thin film resistors, but they are much more expensive.

There are other places where using more expensive resistors make sense. Wirewound resistors have significant inductance unless you use non-inductive designs, and the inductance increases with resistance. However, several years ago, I started to notice that some Mills non-inductive wirewound resistors, a brand I had relied on for many years, were becoming noisy. I read that more recently-manufactured Mills (since the company’s takeover by Vishay in 2011) have the resistive wire element clamped to the end caps instead of being bonded to them, and these connections could become noisy with repeated heating and cooling. I also noticed that the resistors are no longer manufactured in the US, which usually means an attempt in cost-cutting.

I experimented with military-grade Caddock precision power film resistors (one of the few brands still made in the US.) as tube anode loads and they are excellent. They feel substantial, have gold-plated leads and look indestructible. They look even more high-end than high-end audio components; nothing but the best for Uncle Sam. They are non-inductive, non-magnetic and extremely stable at high temperatures. I had to convince a military supplier to sell them to me, and luckily, they didn’t suspect anything nefarious such as building a nuclear weapon in my garage. There are boutique resistors marketed for audio use that cost more, such as those made with tantalum film, but I have no experience with them and the explanations for their supposed superiority do not sound convincing to me. Other audio resistors that use ancient technologies, such as carbon film and carbon composition, are only useful for restoring antique equipment in order to preserve their character, or to add “tone” to guitar amplifiers.

Personally, I tend to be very conservative when specifying the power handling capabilities of resistors, and I usually over specify by a factor of 4 to 5 fold. For example, I would use a 0.5-watt resistor if the steady-state power dissipation is 100mW. This is an important consideration when restoring antique equipment. You certainly don’t want to save 30 cents on a resistor if a short can take out your 300B output tube or damage your output transformer.

The original Quad II amplifier has a 180ohm resistor that is prone to failure. The resistor connects the cathode winding of the output transformer primary to ground (which means it determines the cathode voltage of the amplifier’s two KT66 output tubes), and a shorted resistor would result in a huge increase in the current going through the transformer winding. It is the reason why many examples of this amplifier on the market have tar leaking out of the output transformers; they’ve been damaged by excessive current. The original schematic indicates that the resistor has a voltage drop of 26 volts across it, which any high school student with a calculator can work out dissipates 3.75W. Yet, the actual resistor installed in the amp is rated at 3W. Peter Walker was known to be rather frugal, but it is really inexcusable to save a few pennies on something so crucial. If you are lucky enough to buy a pair of Quad II amplifiers with undamaged output transformers, I would advise changing these resistors to new ones rated at 7W or above before you do anything else.

My Mark Levinson No. 27.5 power amplifier is 27 years old, and after changing all the power supply caps four years ago, it is as good as new. Everything in there was massively over-specified, and it cost a fortune when new, but in retrospect it was actually very reasonably priced after considering how it has lasted several times longer than its less-well-made competitors. I can sell it today and the proceeds will still buy me a very decent new power amplifier.

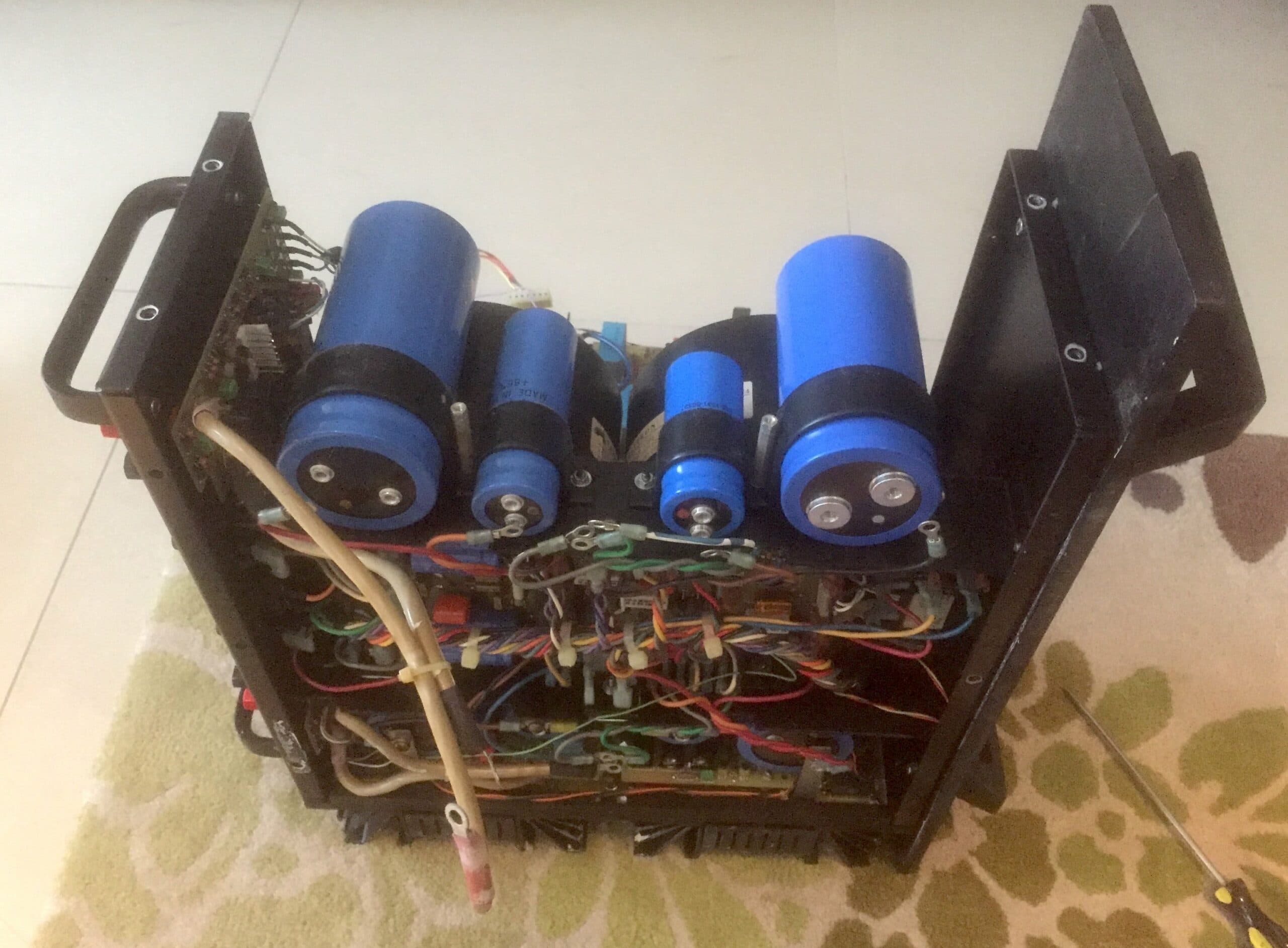

Replacing the power supply capacitors of my Mark Levinson No. 27.5 power amplifier. It took me a while to find the appropriate GE capacitors, one of the few that are still made in the US.

Replacing the power supply capacitors of my Mark Levinson No. 27.5 power amplifier. It took me a while to find the appropriate GE capacitors, one of the few that are still made in the US.Boutique audio capacitors are all the rage amongst many if not most audiophiles. Several enthusiasts have published, on their blogs, listening tests on hundreds of different brands and models. The problem with these listening tests, however, aside from the fact that the testers were not blinded to the identity of the components under test and cost has a large placebo effect (in other words, they didn’t do blind or double-blind tests), was that none of them measured the technical performance of the capacitors. These measurements matter a great deal, as parameters such as dissipation factor, equivalent series resistance (ESR), parasitic inductance, leakage current and dielectric absorption (DA) determine how much a capacitor will alter the signal. The type of film, the quality of the material and the construction all play a role in defining a capacitor’s electrical characteristics.

Teflon has the best dielectric properties (lowest dielectric constant, highest dielectric strength), closely followed by polystyrene, polypropylene and polyethylene. Polyphenylene-sulfide (PPS) has become popular within DIY audio circles in recent years, and I use them in my preamplifier. They have very low ESR and DA, and are very stable at high temperatures. However, they are hard to find and the range of available values and voltage ratings is limited. Most PPS capacitors are of the surface-mount type (due to their resistance to heat during flow soldering), which makes them a pain to work with for DIYers.

Film and metal foil capacitors have better ability to handle large current surges and lower series resistance than metallized film capacitors, and should be used in high-current situations such as passive loudspeaker crossovers. However, they are larger in size, more expensive and, unlike metallized film caps, they are not self-healing (this is the ability of a capacitor to withstand a momentary short or dielectric breakdown under voltage). Teflon film capacitors do have performance advantages in high-temperature environments such as tube amps, but their cost-benefit ratio is steep.

Many audiophiles think of boutique audio capacitors as artisanal products made by dedicated craftsmen in their garages. The truth is, many of these products are made by OEM manufacturers (original equipment manufacturers) that also make industrial capacitors, since only these companies have the economy of scale and the technical expertise required to manufacture to the tight tolerances expected of modern components.

There are products that use different metal foils in their construction, such as tin, aluminum, copper, zinc, silver and even gold. I have not seen any actual scientific evidence that explains why one metal should be better than the other, but there’s the placebo effect at play: having spent a three-figure sum for a capacitor made of precious metal, how can it sound any other way than magical? Some audiophile capacitors use oil-impregnated plastic or paper. Paper-in-oil capacitors were originally developed for higher-power applications for safety reasons, since the oil helps cool the capacitor, prevents arcing between the plates and because these types of capacitors are self-healing. Paper-in oil-capacitors were commonly used in antique tube amplifiers for the same reasons, since these amplifiers operated at high voltages, and partly accounted for their “antique sound.”

The dielectric absorption of a capacitor is the residual voltage remaining after the capacitor has been fully discharged. This residual voltage introduces distortion to the signal, and a low DA is a prerequisite for a high-performance audio capacitor. The DA of a polypropylene film capacitor is around 0.02 percent, and adding oil impregnation will increase the figure to around 2 percent. Guitar players like to use paper-in-oil capacitors to alter the tone of their amplifiers. Why audiophiles want to use them in the signal path of a modern amplifier is a mystery to me, unless their aim is to introduce some distortion into their music.

So, how does one choose which capacitor to use? After all, every manufacturer claims their products to be superior. Some capacitors do have their own particular sonic character, shaped by the imperfections of their performance (assuming a perfect capacitor would impart no alteration to the signal). This then becomes an art form like cooking, where one tries to achieve a certain taste by using different herbs and spices. But if the goal in an audio component is to minimize alteration to the signal, one should choose the highest-performance capacitors based on the measured parameters listed above.

Over the years, my friends and I have tested dozens of boutique capacitors, and we have arrived at the conclusion that price is an unreliable predictor of performance. In fact, one of the most expensive capacitors on the market, claimed to be handmade, had such poor measured performance that installing it would be akin to adding Jalapeno chili to a dish. But even if some of these boutique capacitors have measured well, I have found them frustrating. Used in high-voltage, high-temperature environments, such as for coupling in tube power amplifiers, reliability often became an issue. I have lost count how many times I’ve had to change capacitors due to an increase in noise (having horn loudspeakers with a sensitivity of 110 dB doesn’t help). And thanks to one of these boutique capacitors, I now have a defunct 300B tube that I keep as a daily reminder of my folly. Nowadays, I just stick to good old Wima film and foil capacitors; they are reliable workhorses and are delightfully free of sonic character.

It is worthwhile investing in an LCR meter, which measures inductance, capacitance and resistance, and an ESR meter, which measures equivalent series resistance. The ESR of electrolytic caps rises as a result of aging, which can start to affect the sound of audio equipment well before the capacitance drifts out of range. The electrolytic caps in the power supply of your amplifiers are often rated at 2,000 to 5,000 hours, and the life is shortened by high operating temperature (e.g. Class A operation, or poorly-ventilated equipment placement) and high ripple current. A friend of mine once proudly told me that he leaves his system powered on during the day so that it does not need to “warm up” if he decides to listen in the evening. He was horrified to learn that the caps would only last a year under these circumstances. For normal people who use their systems on average an hour each day, the caps would need replacing every 5 to 12 years. The amp will not break down suddenly, but the rise in the ESR will cause the output resistance of the power supply to increase, potentially causing dynamic compression during loud passages. A final cautionary note: if you decide to check on the capacitors yourself, make sure they have been adequately discharged, as they can store enough charge to electrocute someone.

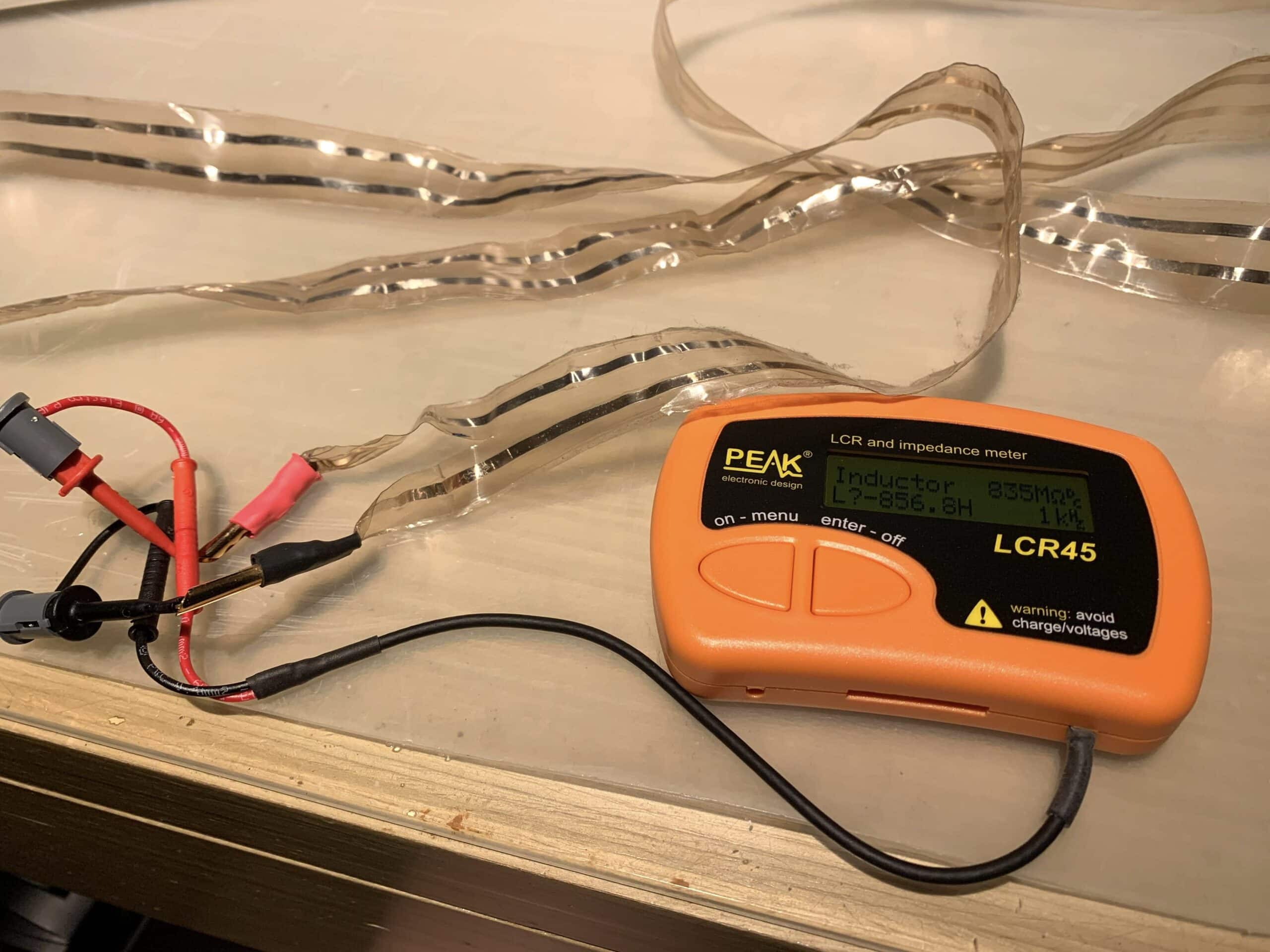

Using the Peak LCR45 meter to measure the impedance of my DIY speaker cable. After reading Max Townshend's article in Issue 124, I measured the characteristic impedance of my DIY silver foil speaker cables. With the conductors side by side, the impedance was 340 ohms. Placing the foils on top of each other reduced the impedance to 30 ohms, which should work well enough for my 16-ohm drivers. Readers with long runs of interconnects should also check the capacitance of the cables to make sure there is no significant high-frequency rolloff. The rolloff frequency is equal to 1/(2 x pi x output impedance x cable capacitance). The output impedance of the equipment should be listed in the owner's manual. I would advise allowing a rolloff frequency of no lower than 100 kHz to minimize change in the phase spectrum.

Using the Peak LCR45 meter to measure the impedance of my DIY speaker cable. After reading Max Townshend's article in Issue 124, I measured the characteristic impedance of my DIY silver foil speaker cables. With the conductors side by side, the impedance was 340 ohms. Placing the foils on top of each other reduced the impedance to 30 ohms, which should work well enough for my 16-ohm drivers. Readers with long runs of interconnects should also check the capacitance of the cables to make sure there is no significant high-frequency rolloff. The rolloff frequency is equal to 1/(2 x pi x output impedance x cable capacitance). The output impedance of the equipment should be listed in the owner's manual. I would advise allowing a rolloff frequency of no lower than 100 kHz to minimize change in the phase spectrum.

Music and the COVID-19 Era

In 1968 we learned about Revolution 9; in 2020 we met COVID-19. Both disruptive, chaotic and confusing, but only the latter delivered unprecedented health and economic duress for so many, with an unconscionable number of lives lost. As we continue to weave our way out of this ghastly pandemic many of us grapple daily with maintaining a sense of calmness and, dare I say, sanity, while increasingly spending more and more time at home.

Research studies have shown that for many folks, music can be a great way of decompressing and escaping day-to-day realities. One can easily get lost in a catchy melody, a great arrangement, or a recording with superior production values. Music can take us emotionally to different places. It can be cathartic, relieving stress and anxiety.

Courtesy of Pexels.com/Andrea Piacquadio.

Courtesy of Pexels.com/Andrea Piacquadio.

Before dinner each evening, I devote an hour or so to an LP or two to decompress from the day and ground myself, along with a red wine chaser. I find this to be quite calming; the music more than the chaser.

When I was a teen, I’d decompress listening to Black Sabbath. Funny, right? Imagine Ozzy Osbourne playing the role of the Great Soother. My poor mother would come into my bedroom yelling, “what are you listening to?” rightly concerned that songs about Satan and witches wasn’t particularly healthy for a teenage boy’s psyche. She had a point. Mom, you’ll be pleased, I have evolved. Now it’s Bud Powell, Bill Evans or Charlie Parker, sprinkled in with the occasional King Crimson.

William Congreve, an English playwright, poet and politician, famously said in 1697, “Music has charms to soothe a savage breast, to soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak.” There was some head-scratching regarding his choice of words – savage breast vs. savage beast – but Congreve refers to the taming of over-exaggerated affections, thoughts or feelings. In other words, he was saying, “just keep it chill.”

Research studies conducted by Stanford University hypothesized that listening to music seems to change brain function somewhat like medication. “Given that music is so easily accessible to virtually anybody,” the study noted, ”it can function as a great tool for stress reduction.”

The study also found a correlation between music with a strong beat and brain stimulation, causing brainwaves to “resonate” in time with the rhythm. Slow beats seemed to encourage brainwaves associated more with a hypnotic or meditative state. Certainly one can see how the rhythmic sounds and varied cadences used in religious ceremonies can impact the congregants’ level of attentiveness, and realize that music with an energetic beat is well-suited for cardio gym classes.

A highly publicized and controversial study done by the University of California, Irvine linked music to health and state-of-mind has been coined the “Mozart effect,” the theory that listening to his music boosts IQ. It’s popularized the idea that music can affect a person’s cognitive ability or mood.

In the study, three groups of college students were given a standard IQ test. One group spent 10 minutes listening to a Mozart piano sonata, one group with a relaxation tape, while the third group had no stimulus. The findings indicated Mozart’s music consistently boosted respondents’ test scores. (Though many have questioned the study’s validity, just think how many CD’s Mozart could have sold via a late night infomercial.)

Another study examined how music affected surgical patients. Half of the patients in a cataract surgery study received ordinary care, while the other half listened to the music of their choice via headphones during the procedure. Before the surgery began, not surprisingly, the heart rate and blood pressure for all participants was pretty jacked, a case of pre-surgery nerves. While the non-music-listening group remained hypertensive throughout the surgery, the BP for the group listening to music came down rapidly – on average, 35 points on systolic (the top number) and 24 on diastolic (the bottom number) – and remained that way throughout their in-hospital surgical recovery period.

The Artist’s Perspective:

How has COVID-19 impacted today’s artists, the music makers? Musicians in the modern-day era make their money from touring, and with COVID-19 that’s pretty much been verboten. Conversely, many of us mere mortals can work from home and use platforms like Zoom as our portal to colleagues and the outside world. Of course, musicians can do virtual concerts, but for many, their music doesn’t translate well to online platforms, or there are concerns about sound quality and production value, and/or they perhaps simply lack the requisite technological or database marketing skills to connect to their fans online.

Just how pervasive has livestreaming been? In 2020, Bandsintown, a concert discovery and hosting platform, registered over 62,000 livestreams on its site over a nine-month period, with 80 percent of fans indicating a willingness to pay for access. This trend, no doubt, will continue. Even though virtual performances may lack the emotion, intimacy and interaction of an in-person experience, the wide reach of the internet does create opportunities for greater exposure to artists’ material.

I recently reached out to jazz pianist and composer Emmet Cohen to talk about the challenges that artists are facing during COVID-19, and how he has adapted to producing weekly live video streams from his Harlem (New York) apartment. The series is called “Live From Emmet’s Place.” In addition to leading the Emmet Cohen Trio, Cohen has performed with acclaimed artists such as Ron Carter, Benny Golson, Jimmy Cobb, George Coleman, Jimmy Heath, Tootie Heath, Houston Person, Kurt Elling and Billy Hart, among others. He’s also the winner of the 2019 American Pianists Awards and the Cole Porter Fellow of the American Pianists Association.

Stuart Marvin: Hey Emmet, how are you and how are your livestream gigs going? I think to date you’ve produced over 35 weekly video streams directly from your NYC apartment – is that right?

Emmet Cohen: Well, the cops showed up the first time. We basically pled our case that this (our apartment gig) is all we’ve got right now. We only do it once a week for two hours, after [working hours] and before people go to sleep. [The neighbors] were cool. People now send us gifts, like bottles of wine, as a thank you. We try to be as nice as possible.

SM: What’s been the evolution of your livestream production?

EC: We had a tour date scheduled in Lawrence, Kansas in March. The show was cancelled due to COVID, but the venue offered us our full fee if we’d do some sort of web stream, to do something good for the world, put something out there, and it would be like our gift to the community. We said sure. That was our first foray. The sound was terrible, like listening to a Game Boy. With “Live From Emmet’s Place,” I’ve tried to improve the sound and video quality each and every week. It’s been an ongoing learning experience. We eventually got some new microphones, a mixing board with 8 inputs, 4 cameras, and a switcher, and I spent hours at night studying open broadcast software on YouTube. A whole quarantine’s worth of research. A lot of trial and error. A lot of failed attempts to get it right.

SM: How has your streaming audience grown since you started?

EC: We did the first one and it [drew] about 40,000 to 50,000 views. And we were like, wow, this is more than anything we’ve ever done before. People really responded to it. They wrote me notes saying we really needed this, and that has continued for 35 weeks. It’s been a slow, gradual build. Between Facebook and YouTube we’ve generated between 30,000 to 120,000 weekly livestreams. People were very thankful and they wanted to know how they could support us. It’s a very symbiotic thing.

SM: Live streaming is a whole different form of audience engagement. What have you learned?

EC: Jazz is all about community. I’m so lucky to have the members of my band, the Emmet Cohen Trio, as part of my community. They lift me up. They’re there for me when I’m working on the tech side (video and sound production), and when it’s time to come back to the music they’re there to ground me right back. They understand my new role and have empathy. It’s incredibly soulful and magical, and not something I could have done alone. Streaming is just another place where jazz has adapted and do what it’s always done in the world, which is connect people, uplift them, offer hope and provide a sense of belonging. Music has always been inclusive.

SM: Tell me a little bit about your business model.

EC: We have a membership platform called Emmet Cohen Exclusive. It’s subscription (premium)-based, and a way for us to keep the livestream free for everyone on the internet, cause a lot of people are going through tough times, and I thought it was important to keep the music free so people can see it and share it. And so we can touch all corners of the world. The Exclusive membership is an opportunity to get further involved, and if a CD or record comes out it gets immediately mailed [to members]. It’s kind of a community of people that helps us do what we do.

SM: How are you balancing quarantine and safety?

EC: We have to be careful, but I’m lucky to have a band that’s more than a band; we’re family. Also, Harlem (Emmet’s neighborhood and where he livestreams) is pretty special and has always been about the power of community. It’s where Billie Holiday lived, where Duke Ellington lived. Sonny Rollins [lives here]. It’s where Langston Hughes and James Baldwin walked the streets. It’s a really historical place, which adds to the majesty of what we’re doing.”

Check out what Emmet Cohen’s up to at emmetcohen.com, and look for his soon to be released debut recording, Future Stride, on the Mack Avenue label.

2021 and Beyond:

The past year brought about a “pivot” to compensate for a lack of artist touring, which lead to livestreams, expanded catalog offerings, and new and different merchandising ideas and options from artists and labels. That will likely continue even after the touring industry returns to something approaching normal (whatever our “new normal” may be).

In the case of some classical performances, for example, producers made a virtual experience more engaging and entertaining by including pre-recorded video interviews with a conductor, adding an up-close and personal feel to a performance. Prior to COVID-19, orchestral concert footage was often videotaped for archival or promo purposes or to enhance an artist or venue’s website, but with no significant focus on production values. The pandemic changed all that and has led to investment in audio, camera, lighting equipment, editing software, and tech personnel, to enhance a performance’s production and entertainment quotient. Now, virtual orchestral or opera producers will literally break down scores and block cameras in pre-production, just like a director would do with a film or TV script.

Moving forward, deploying a combination of livestreams with tours could potentially deliver a more efficient business model for artists, with both pricing and the value proposition on virtual performances likely to evolve. Nothing is as good as a live in-person performance for both the artist and the listener, but on the other hand, livestreaming can broaden an artist’s reach to a wider group of fans, as many secondary and tertiary markets don’t economically warrant an in-person tour stop.

Courtesy of Pexels/Brett Sayles.

Courtesy of Pexels/Brett Sayles.

We’re likely going to see more and more hybrid business models (combining tours and livestreaming), with the industry becoming more and more data-driven with investment in technology, staffing, product bundling, price elasticity testing and so on, all designed to optimize fans’ entertainment value and artists’ cost-efficiency and revenue.

What role, if any, will streaming services like Spotify, Amazon Music, Qobuz or Tidal play in this new paradigm? How about Live Nation? Is there a complementary opportunity for these platforms with livestreaming? Some are already fairly engaged, but with performers having to pivot away from touring, we’ll likely see far greater involvement by these platforms and services. Livestreaming can also be a great discovery tool for up and coming artists, especially for those who have a strong stage presence.

More ambitious virtual concert models will also likely leverage digital’s two-way capabilities to drive new kinds of engagement between artists and fans. This could entail, for example, set lists curated in real time by the virtual community. While everything might still pale in comparison to a live in-person concert, making the audience visible and interactive builds on that sense of community. From a technical standpoint, however, there are latency and audio sync issues that make it extremely challenging to align hundreds of thousands of livestreams across the globe.

One thing is for sure; in 2021 and beyond, technology and business models will continue to evolve to facilitate meaningful exchanges between artists and their fans.

Header image of Emmet Cohen courtesy of Taili Song Roth, cropped to fit format.

My Massive Income From Streaming

Our Paul McGowan asked me to recount the truly massive amount I’ve made from streaming sources. So here it is. But first, while I won’t reveal the figure, I will say that prior to Napster, prior to everyone thinking that music should be free, the Sheryl Crow album I worked on made me a pretty healthy income (thank you, Bill! It was called Tuesday Night Music Club.) There have been quite a few other projects I’ve made money from, but TNMC is the big one.

Now music is free. As I type, Susanna Hoffs and I are trying to figure out how the finances of the record we did way back when will work out. I’ll buy a recording from an artist I know I like (Shriekback, the Firesign Theatre, etc.) But otherwise…

TNMC was an album we did for A&M Records, now owned by Universal Music after a number of mergers, and in turn, Universal is now owned by a French toilet company called Vivendi. Or is it? [They’re still part-owners; I had to look it up. – Ed.]

I’ve lost track. Who owns it now? And whoever owned it at the beginning of streaming definitely didn’t have the writers of the music they were making money off of in mind when they assigned rights to stream the music.

Are you ready for the enormity of the size of the check I’ve received from streaming services – the one single check?

$0.01.

One cent.

One bloody, red cent.

Of course, I didn’t cash the check. It was too good of a commentary on the state of the finances around music to throw away, though – but I’ve lost track of where I put it.

This isn’t quite the whole truth of what people like me get from streaming. Where in the past, I held onto my publishing rights (50 percent of the income from a song) until I sold it*, that income from all sources now goes to Sony, and Universal gets the lions’ share of the rest of the money, which no doubt they made a stock trade for – or some such maneuver. Once or twice a year, I get a statement from Sony that reports there was too little revenue to bother to pay me. My BMI payments on occasion approach relative significance – for song usage – and I get AFM (American Federation of Musicians) payments once a year that can be noteworthy, owing primarily to being one of 500 participants in Michael Jackson’s Dangerous album.

But as a writer, there’s virtually nothing held over from the world-as-it-was.

*Although other writers on that TNMC album spread rumors about me making more than anyone else, it’s not true – as a percentage of my income from the album, yes – I made 100 percent. But that was the smallest hunk of the total proceeds, owing to my unawareness that I needed to be aggressive about such things as publishing. The other writers generally made publishing deals as a way of getting some money earlier in their careers. When you make a publishing deal, typically the publisher takes all of that income. I didn’t, so I made 100 percent of everything there was to make from my songwriting. And for a time, it was a good income.

PS: I should say, I did some of Phoebe Bridgers’ first recordings – she was a schoolmate of my daughter’s – and she was doing okay before the shutdown of the universe. I couldn’t – and didn’t – advise her about what path to take, When I was that age, the path was clear – you just had to be really good or really lucky. She said she couldn’t imagine doing anything else and being happy, so…

Header image courtesy of Pixabay/Olya Adamovich.

January's Most Memorable Concerts

When you run through a list of the biggest rock concerts of all time, one thing you’ll notice is that most were held during the summer months. I guess this isn’t much of a surprise, although there are actually a fair share of exceptions that took place in the spring and early fall. But guess which month is largely absent of almost any big shows? If you guessed January, you win.

Even December has made more noise, hosting its fair share of memorable and infamous moments like the Rolling Stones’ performance at Altamont in 1969. Things just seem to come to a halt in January. Frankly I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s because the holidays take the wind out of concert-going crowds. Maybe weather plays a role. But as I look back at my own personal concert-going, the month of January has always been light.

That’s not to say that there haven’t been significant January concerts or even shows that changed the face of music. For example, the legendary Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite show that Elvis Presley hosted on January 14, 1973. I remember watching that as a kid and being dazzled by the fanfare built around a new technology breakthrough: the first live concert broadcast via satellite. That enabled The King to go global. The concert delivered better viewing numbers than any moon landing. Then there was the Trips Festival in 1966. 10,000 people attended this three-day event that featured bands like the Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. This festival put concert promoter Bill Graham on the map and became a psychedelic landmark, one of the first events to pose the question: “Can you pass the acid test?”

Then, there was that crazy moment in 1978 at Randy’s Rodeo in San Antonio, Texas, where the Sex Pistols took to the stage. From the get-go the band tirelessly taunted an audience of mostly cowboys with insults and digs. Things reached a boiling point when Sid Vicious hit a patron in the head with his bass. It became a definitive moment in the world of punk where the line between art and life became largely blurred.

These all were significant live music moments, but it’s hard to imagine how any past or future performance in the month of January could possibly top the one I’ll name as the greatest of all time.

The Sex Pistols, 1977. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Riksarkivet.

The Sex Pistols, 1977. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Riksarkivet.

I’m speaking about Johnny Cash’s performance in front of about 1,000 inmates at Folsom State Prison in 1968. Much like the comeback special that Elvis would host later that year (not to be confused with the Aloha From Hawaii show mentioned earlier), this performance catapulted Cash back to the forefront of American music. Prior to this appearance Cash’s career had hit the skids, derailed by an addiction to pills so strong that it had him contemplating suicide. But on Saturday, January 13, after two days of rehearsal in a Sacramento motel and with a new producer and the approval from Governor Ronald Reagan Johnny took to that stage in his trademark black ensemble. Backed by a small, tight band, he sat on a white stool and introduced himself to the crowd with the immortal words, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.”

What many don’t know is that Cash insisted on two performances, one at 9:40 am and another at 12:40 pm, in the event the first show wasn’t fit for recording. In both cases Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers opened the show, each singing a song or two. From there, Cash was introduced and he ripped right into “Folsom Prison Blues,” The performance was later released as a live record, Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, and would become his best-selling disc to that date. It also would provide him with a new footing that convinced June Carter that he was back on track. They married shortly thereafter.

Many artists, across genres, consider this live record to be a seminal work of American music. Longtime Cash sideman (and son-in-law) Marty Stuart once said, “if I had to point to one record – if you’ve never heard rock and roll in your life, if you’ve never heard country music in your life, go get this record. If you want the definition of American country music, American rock and roll, whatever Americana music is, here it is. If I had to take one record to Heaven with me, it would be that one.”

Cash was no stranger to jails. He had been locked up over the years for public disorder, drug offenses, public intoxication, and breaking curfew while picking flowers in Starkville, Mississippi. That last brush with the law even inspired his song “Starkville County Jail.” Those experiences stayed with him and informed his writing.

In the early 1960s after Cash had written “Folsom Prison Blues,” prisoners across the country wrote letters asking Cash to play for them. Truth be told, he had actually played at various prisons before the idea to record his shows was proposed for Folsom. During these visits, Cash took the time to sit down with inmates from Arkansas to California and hear their stories. Through these moments he became their champion.

Almost a year after Folsom, Cash returned to California to play at San Quentin State Prison. Ironically, among the group of inmates was Merle Haggard. He would later say of Cash’s performance: “It gave everybody the feeling that if they could learn [from] “Folsom Prison Blues,” maybe they could stay out of prison.” June Carter Cash described the day as the moment they had come to “see the lost and lonely ones. Some kind of internal energy for those men – the prisoners, the guards, even the warden – gave way to anger, to love, and to laughter…a reaction like I’d never seen before.” In Johnny Cash the inmates at Folsom and San Quentin found a brother, and the photos and footage from both shows reveal the joy and the sense of hope that he brought to them. Apparently for Cash, performing at these correctional facilities was an important reminder of where he would be headed if he didn’t get control of his own personal demons.

This dedication to bringing music to inmates would move beyond Johnny Cash and extend to B.B. King’s Live at Cook County Jail in 1971 and even Metallica performing at San Quentin in 2003. Cash started a movement at Folsom in more ways than one. What few now know or remember about his prison tour is that he donated a portion of proceeds from their hit albums to prison reform campaigns, and in 1972 Cash testified in front of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on National Penitentiaries. He also sat down with President Richard Nixon to plead his case.

These Cash performances at Folsom Prison are in my opinion the centerpieces of his eternal legacy. They are the perfect intersection of his music, his qualities as a performer, his humanity and his own sense of justice. An otherwise musically quiet day in January was the spark for a body of music that still can change just about anyone’s mindset and mood. Listening to Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison is a great way to kick off any new year and after the one we’ve just lived through, now might be the perfect time to tap into an electrifying performance that was truly transformational – exactly what we all are hoping for from 2021.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Abernathyautoparts~commonswiki (assumed), cropped to fit format.

Hanging With Les Paul

Les Paul certainly had a major impact on me, especially since I got to hang with the guy a few times.

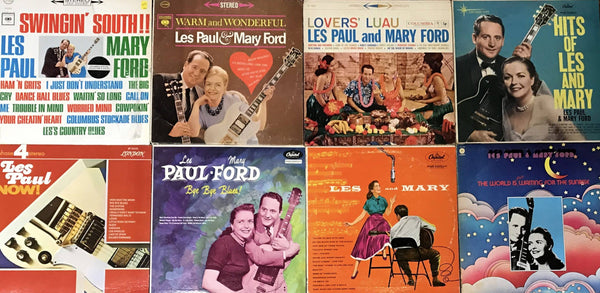

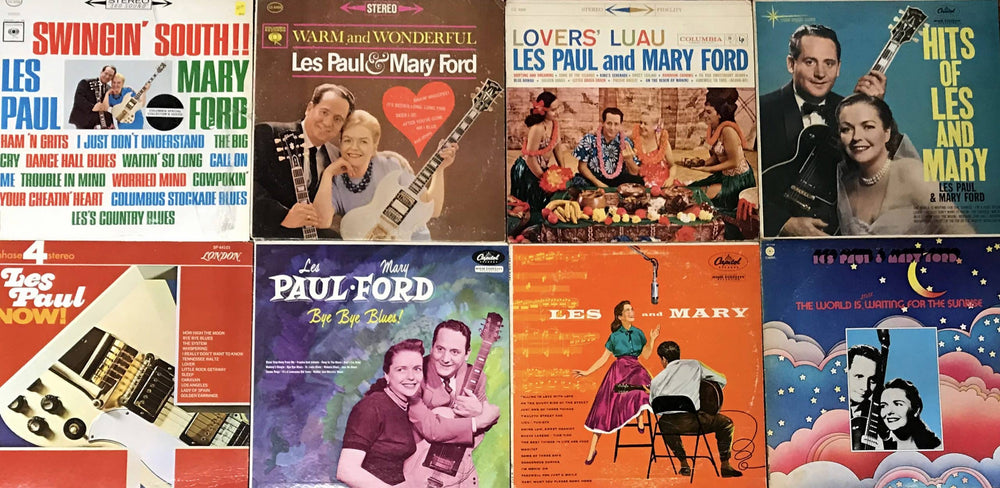

In 1991 I was working at The Absolute Sound when a CD box set, Les Paul, the Legend and the Legacy arrived at the office. It was an excellent compilation of Les Paul and wife/fellow performer Mary Ford’s Capitol sides from 1947 through 1958.

The CD package came with press information, and, thinking quickly for once in my life, I saw this as an opportunity to interview Les Paul. I figured it was far from a certainty – after all, this was Les Paul, guitar legend. And I’d heard he could be difficult and had an ego. But I knew the man’s career and music, made a convincing pitch to Capitol’s PR person…and they said, “Come down to Fat Tuesday’s (the Manhattan club where Paul played on Monday nights) and you’ll be able to interview Les about an hour before the first show.”

A couple of weeks later it was time to drive from Sea Cliff, New York into Manhattan. I had brought my 1984 Les Paul Standard gold top for Les to sign. I loaded up my 1992 Honda Civic and drove away…but something didn’t feel right…

After driving about a mile I realized that in my excitement over being able to meet Les Paul I had forgotten to load my guitar into the car! I had left it in the street!

Panicked, I drove back to the office. I pulled up to the spot where I had left the guitar and it wasn’t there. Crushed, I went to the office to call the police (no cell phone in those days)…and saw an elderly man standing at the door with my guitar in hand. He had found it in the street, saw the TAS business card that was taped to the case and had gone to the office to return it. After I proved who I was, the man gave it back to me, refusing any kind of reward.

What a way to start the trip. Every five minutes I’d turn my head and look in the back seat to make sure the guitar was still there.

I got to Fat Tuesday’s and there was Les Paul, hanging out by the small stage in the small room, kibitzing with the other musicians, his son Rus and some other people. He still had some tinges of red in his hair (before making it as Les Paul he was known as Rhubarb Red), was wearing a turtleneck and old-man pants, and was thin, smaller than I’d imagined him. I was introduced to Les. “Hi, so you’re the guy from the magazine who’s going to do the article!” Les practically yelled it out in a gravelly yet friendly voice. He shook my hand, eyed my guitar case with a smile (said case in my left hand in a vise grip) and said, “C’mon, let’s go!”

He led me to a tiny back room with irregular dark walls and exposed pipes, boxes of food and liquor and a small, battered table. I’d pictured a fancy green room but nope; the two of us barely fit. Clearly, Les Paul wasn’t a man of affectations. I laid out my tape recorder and notebook and Les bellowed, “well, go ahead. Ask away!”

I was tongue-tied. I This was my first interview with a bona-fide legend. Sensing my nervousness, Les looked at me and said, “I know, I know…you’re all alone in a room with LES PAUL!” He said it in such a self-deprecating manner that it was a perfect way for him to break the ice. We laughed, then I looked at my notes and said, “I had all these questions I was going to ask you but now that I’m sitting with you, it doesn’t seem right.” He replied, “OK, let’s just talk. Ask me anything!” Which we did. Portions of the interview, which originally ran in The Absolute Sound in 1992, are included below with permission of TAS, along with a link to the complete interview. We talked about the beginning of his recording career in the 1920s, his early experiments with guitar amplification, his working with Mary Ford, specific recording techniques, his favorite guitarists and a lot more.

Then it was time for him to do a soundcheck with the rest of the musicians, long-time second guitarist Lou Pallo (who passed away in 2020) and I think Gary Mazzaroppi on bass (I’m not sure). Les picked up a brown sunburst Les Paul that looked somewhat customized (many of his onstage guitars weren’t stock), plugged into a seventies Fender Twin Reverb house amp, and played a few notes.

What is that indescribable something that defines a great artist? Their sound. Their tone. It’s the combination of the way they attack, hold and release the notes, the dynamic shadings of their touch, their timing, the spaces they leave between the notes…and an X factor that maybe none of us will ever understand, including the artists themselves. Les was playing 10 feet in front of me, and time stopped. There it was. The sound. THAT sound. Oh my god.

The rest of the band joined in and ran through snippets of a few songs to make sure the levels were right. Before leaving the stage, Les looked at his guitar, made a face and said, “you know what? This guitar is a b*tch!” I thought, here’s a guy with dozens of guitars in his house, who could play any guitar in the world, and why is he using one that’s hard to play? (Never got the answer.)