[Originally published in Goldmine magazine—Ed.]

While at the listening session for the new Giles Martin remixed White Album and associated demos, I experienced how much Giles sounds like his father, George. In manner, style, and cadence…but younger. If I closed my eyes, I could almost hear George, which, I guess, was almost fitting given what I was about to experience.

The Giles Martin re-imagined White Album remixes, along with Giles’ voice and mannerisms, make listening to the White Album the same…but very different.

To many of you, Beatles freaks, who were hoping (but not sure) if the White Album would be subject to the same kind of marketing blitz of multiple versions and remixes of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band…You should know that the 50th Anniversary release of the White Album is even grander (if that’s possible) than Sergeant Pepper’s.

The inclusion of many of the legendary Esher Demos, the actual 4-track demos individually made by John, Paul & George, ultimately led to the songs that comprise the 30-track double White Album released on November 22nd 1968, a mere 5 years since Americans heard “I Want To Hold Your Hand” for the first time (not to mention the 5th anniversary of the Kennedy Assassination!)

The weekend of the 1968 release of the White Album, I was attending a 48-hour drug-fueled (mostly psychedelics) party at my friends apartment on the Upper West Side in Manhattan.

It seemed that everyone brought a copy of the album.

We listened to it, side to side, track to track (as God intended vinyl to be heard), in order, nonstop.

We didn’t know about the fights: First Ringo quit, then returned to a relieved and warm welcome back from the others; then George quit (he actually argued with Ringo as to who quit first!); then sound engineer Geoff Emerick walks out, refusing to accept John Lennon’s pleas to stay, and never returns to the project, leaving the job to several others.

I can’t speak for the others, but as a fan I knew nothing of what was really going on in terms of the songs meanings and derivations.

I didn’t know that most of the songs were written in India during the Maharishi retreat period. I didn’t know that this may have been the sound of my favorite band on the verge of a breakup. The only report I read was in Rolling Stone, and it informed that “Martha, My Dear” was about Paul’s sheepdog.

That was about it.

We were all blissfully high and reveling in a 30-track double album by our favorite band. We were loving every minute of it.

Now we know all. Here are some tidbits:

“Bungalow Bill” — A real guy living in the Ashram.

“Dear Prudence” — Prudence Farrow (Mia’s sister), too shy to come out of her bungalow while John & Paul serenade her outside her window.

“Helter Skelter” — Paul wanting the band to sound louder than The Who.

“Sexy Sadie” — Change the phrasing to Maha-rishi and then sing all the lyrics as written. The song is an expose (as Lennon saw it) of the Maharishi’s hypocritical manipulations of a woman at the ashram.

You get the idea.

As fans, we knew none of this at the time.

In the intervening years, we now know (maybe too much) about everything concerning the Beatles.

I’m always torn between my Beatles research, my desire to remain just a fan, and whether they can co-exist (like there’s a choice!)

Now, 50 years later and as a journalist, I sat in the listening studio at Power Station with about 30 well-known music industry Beatles professionals, some of whom know way more than I about the life and times of the Beatles. Many of these people have written the very books that have informed me. The difference between me and most of them?

I have a life!

I can always listen just as a fan, but as a musician, producer, and now journalist, I wanted to know more about the technical side of the process.

Giles was very accommodating, funny, self effacing, and quite honest.

Here is my interview with Giles Martin:

JJF: Was the White Album totally remixed in the native Hi-Res digital domain?

GM: Yes. All the tracks, mostly 8-tracks (some 4), were transferred into Hi-Res digital and then used to remix the album.

JJF: Were Paul & Ringo present during the mixes?

GM: No. I’d go to Ringo to play him stuff, and Paul came to me.

JJF: Anything they didn’t like?

GM: Not really. They know what they like and want as well. There’s an element of trust there because they know I’m not doing this to further my career, if that makes sense.

JJF: My friends, mainly musicians, come to my house and I play the remix of “Sgt. Pepper’s.” The first thing they notice is that the drums sound like John Bonham and Paul’s bass sounds like John Paul Jones. I make the joke: Well that makes sense, those two are the only living members (Giles laughs)…Are you conscious of the fact that the drums and bass are so prominent?

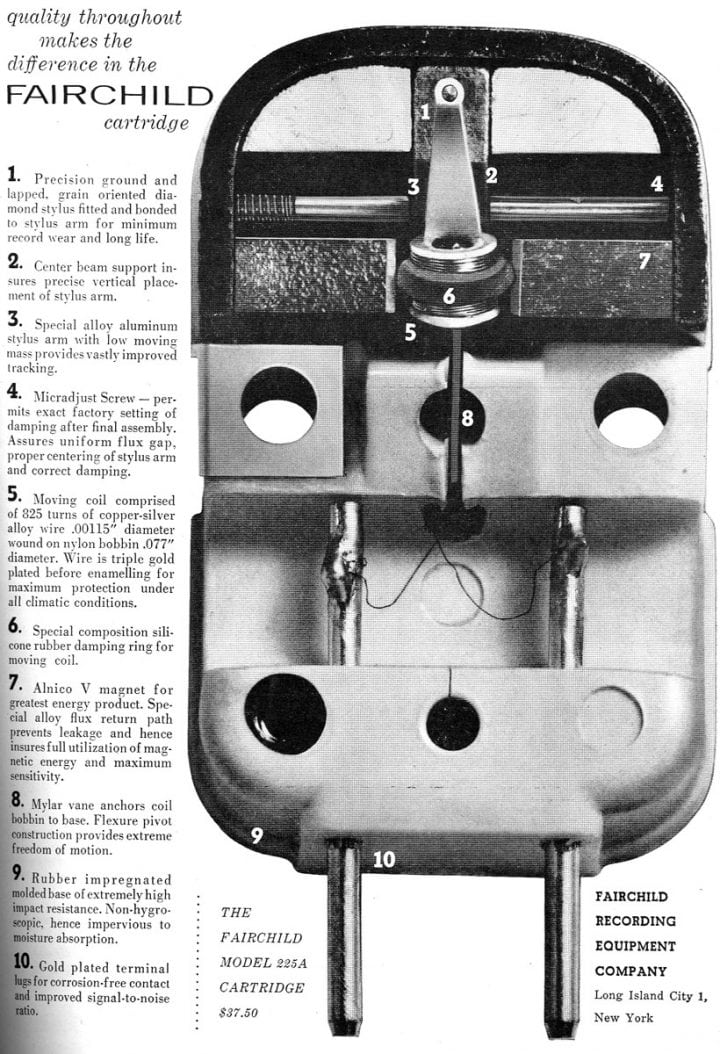

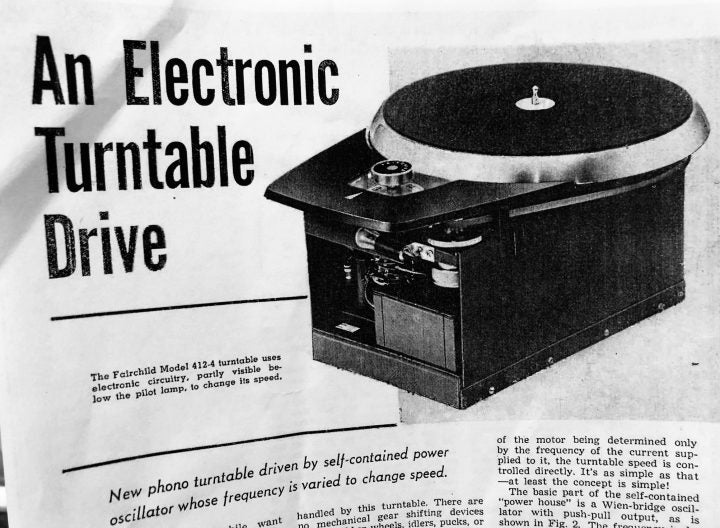

GM: The fact is that I don’t have to limit things with compressors. I can have more low-end in the mix because I don’t have to worry about the needle jumping out of the groove (on a record). All of these things result in more dynamism.

But essentially, it’s what was on the tape (originally recorded). There were very few clean drum takes on Beatles records. On Sgt. Pepper’s we had isolated drum takes on “With A Little Help From My Friends” and “Lovely Rita”.

“A Day in the Life,” for example, was hard to mix because the bass and drums were on the same track.

The White Album was mostly 8-track. On the White Album, there were a few discreet (meaning isolated) drum tracks.

JJF: Your dad has been quoted as saying that the White Album would have been much stronger if it was just a single album. Did he ever tell you what tracks would have made the cut for a single album?

GM: We never really discussed the Beatles, funnily enough. When I ended up doing Love — because Love was so ridiculous and seemed like a bad idea the time — I thought that if I was going to get fired and I had only one legacy, I would back up the tapes so at least I’ve done something (none had been digitally backed up at the time).

I listened to everything, made notes, and played them for my dad. That was the only time I talked to my dad about the Beatles.

JJF: Do you have any favorite tracks on the White Album?

GM: “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” (in the general listening session, Giles spoke about the song as a very special arrangement that always kept changing) and I kind of like “Blackbird” because my kids sing it. It’s a clever song.

JJF: In general, what would you say is the overriding purpose of the remixes?

GM: We try to peel back the layers between what’s on tape and what you listen to at home…make it sound like a record with less shit on it. We have everything at our disposal that they had (at the time). We have all the old Vox’s, we had all these choices. The old red TG desk, we have plugins and I work out how we can take things off and still keep the record.

It’s the vibrancy on tape that’s so important.

JJF: I always explain to people that you can never get any closer to an artist’s recordings than what a producer hears at the mixing desk. Having said that, how much closer is the White Album mix today, compared to what it was 50 years ago?

GM: I think we have the advantage, despite what people say. The worst listening environment now, is better than the worst listening environment then. Now, more than ever before, we can get the listener closer into the control room.

JJF: Will Rubber Soul and, by extension, Abbey Road be getting the same treatment?

GM: I can honestly say: There are no plans. I’m always surprised to get through one of them. I would never say never, but right now there are no plans. It’s never been discussed…

JJF: What surprised you at the White Album remix sessions?

(It’s important to note, before Giles’ response, that the reason for the question had to do with all the stories that the White Album, because of the infighting, was like 4 solo albums. Here, for the record, is the actual breakdown: 17 tracks had all 4 Beatles playing, 4 tracks had 3, 2 tracks had 2, and 7 tracks had 1)

GM: The biggest surprise was that it was a band working together. The biggest surprise to me, was that I thought it was a conflict album. It was certainly conflicted with my dad because it wasn’t going in the direction (meaning control) that he wanted to go.

Some people want to believe that they weren’t playing together in the room.

What I heard in the music (and talking in between takes) was congeniality and collaboration.

JJF: Thank you Giles!