No, this is not another “confession’ about past drug use.

It’s a review of an amazing stylus cleaner.

First though, I knew that my story about how I dealt with my prostate cancer would hit a nerve (no pun intended).

I read every story and I also received more comments directly. All the stories about the process of discovery and then the aftermath have been emotional, heartfelt and I appreciated all of them. I also want to thank those who simply wanted to wish me well and appreciate my honesty.

Now, getting back to audio, I am about to give a huge ‘thumbs up’ endorsement of an item that I never thought I would ever care so much about:

A revolutionary stylus cleaner made by DS Audio: The DS Audio ST-50 Stylus cleaner.

The same DS Audio that has recently made such a big splash with their out-of-the-box line of optical phono cartridges.

Here then is yet another out-of-the-box audio item and its an accessory that is as inexpensive as it is innovative.

I never thought that I would ever really write any reviews but I can’t see any other way to describe this.

Yes, this deals with analog and yes there is an audio cartoon with the caption “The thing I love most about analog is the expense and the inconvenience!” I agree with this.

The ritual of vinyl playback is, in fact, a ritual and to many observers (my wife included) there is a lack of understanding that this is actually something that is enjoyable. Those who partake know what I mean…

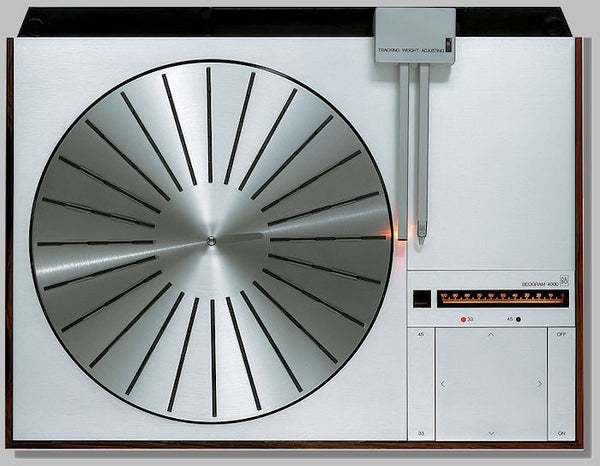

Back when I started listening to records seriously, around 1968— I just took out an album (always carefully) placed it on my trusty AR XA turntable, played the record, took off the album and put it back in the jacket and, probably played another album after that.

Well, that was then…

Now the higher the food chain of analog gear, the greater the ritual.

I now stand at about the peak.

I take out an album, wash it on my Audio Desk vinyl system pro (that takes 6 minutes alone), place it on the turntable, then I set the preferred speed -33 or 45-on the outboard power supply for the VPI Avenger Reference TT, put on an outer ring clamp around the album, then place a record weight on the spindle, clean the stylus and then ….play the record.

I can do all this (minus the record washing machine) about as quickly as a seasoned barista at Starbucks can conjure up a vanilla mochaccino decaf half latte.However When my friends see this they just start wondering if I should be committed.

They usually shut up when they hear what comes out —but this is another story.

The most harrowing period of this exercise, however, is cleaning the stylus.

Back in the old days of cleaning cloths, dust bugs and disc washers to remove dust, we didn’t really worry about the damage done to a stylus when dragging a brush over it to remove the obvious dust left behind from a previous record.

As time passed and everything became more expensive and more revealing, the issue of clean records and clean styli became much more important.

On the actual vinyl side of things this has led to record washing machines of ever increasing sophistication. The cost of these machines over time has risen from $200 to now close to $4,000 for a state of the art unit.

The more transparent the vinyl playback, the more you want to remove anything that can get in the way of the transmission of groove information to the cartridge.

After you get the actual record as clean as possible then what?

Well, stylus maintenance is the next logical step.

When we were all young, stupid, and stoned, and we all owned Shure M91’s or V15’s or Stanton 500’s etc. it may have seemed easy enough to either blow away the dust or take a little brush to remove what we could see.

I have even used my finger in those days.

But today, with state of the art cartridges selling from $750 to $15,000, there had to be a better, more effective way.

I have many different brushes and even stylus cleaning liquids but, every time I drag either the dry or wet brush across the stylus tip of my Dynavector XV-1S ($5600.00) I wonder if the force I’m applying is pushing the cantilever into the magnet assembly causing some kind of damage or, even worse, pushing the brush the wrong way and breaking off the stylus completely.

I have heard many a story from audio salesmen I know about the customer who wrecked his $15,000 Clearaudio Goldfinger or $10,000 rare & discontinued Koetsu just this way.

On top of that, even the removal of dust is no assurance that the tip is really clean. Truth is…is isn’t.

Gunk adheres to the stylus tip and the heat of the friction of the stylus as it pushes through the grooves, at ever increasing velocity as the record spins toward the end of a side, keeps this junk on it.

And then I read about the DS Audio stylus cleaning pad.

Not a brush, a pad.

A pad made up of a Urethane resin gel like compound designed originally for “clean rooms”.

You simply place the pad on your turntable (without the record) and lower the arm so that the stylus drops onto the pad at its own preset weight (ave. 2 grams). When you raise the arm you will see the dirt (a white spec) that is left behind. Lift the arm, move the pad just a little by rotating the turntable platter and repeat the process. Do it once more (recommended 3 times).

When the stylus ‘sinks’ into the pad the urethane compound pulls off all the gunk

You must make sure that the stylus is off the pad before you move the arm or pad to repeat the process.

What is left on the pad (white speck residue) is all the crap between your record and your cartridge. The garbage that you now see on the pad is stuff you can’t see with the naked eye just looking at the stylus and now visible on the pad in plain sight.

How really effective is it?

I have washed a new album, played it once and dropped the stylus onto the DS ST-50 Stylus Cleaner pad after playing the ‘clean album’.

It always has gunk on it. Always.

So what this process does is give you, in essence, is a new stylus every time you play a record.

Remember when you put on a new cartridge and played your favorite record. Remember the thrill of feeling how clean and clear the music sounded?

Now you can have that sensation every time.

And the best part is that the pad can last years because it’s easily washable and what’s more it’s…. inexpensive. $80.

So inexpensive that the price justifies its use at just about any level of analog from a $475 Rega Planar One with an Elys phono cartridge to a $100,000 + TechDas Air Force One with the most esoteric of cartridges.

If you love analog, this item is absolutely indispensable.

That is, if this added new ritual is something you are comfortable with.

If not, then my wife would suggest just you just play a CD or stream….