[Back in Copper #44 I devoted a Vintage Whine column to the 60th anniversary of the single-groove stereo disc, first launched by the small American indie label Audio Fidelity. As there was a lot of interest in that piece, John Seetoo interviewed Andrea Bass, daughter of Audio Fidelity founder Sid Frey. In issues to come, you’ll see more stories about Audio Fidelity and its artists. —Ed.]

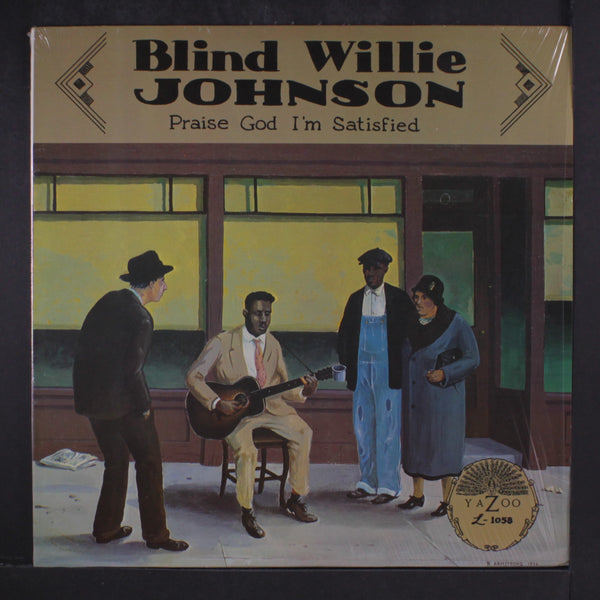

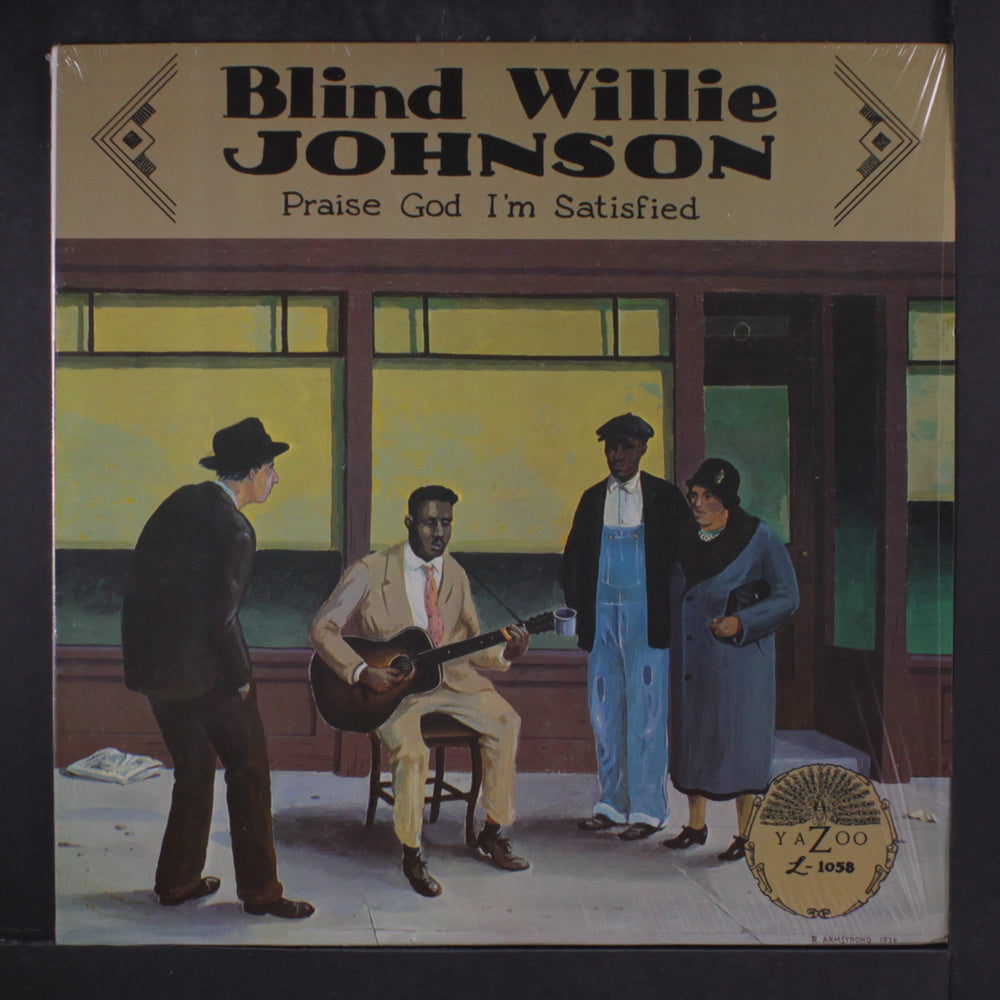

Audio Fidelity’s name in the annals of recorded music was secured when the label released the first commercial long playing stereo record in 1957 of the Dukes of Dixieland with recordings of trains on the flip side. Founded by entrepreneur Sid Frey, Audio Fidelity went on to amass an eclectic cross genre catalog of Bossa Nova, Hawaiian, Jazz, classical organ, marches, bagpipes and sound effects releases, among others.

Growing up in New York City as the daughter of “Mr. Stereo”, Andrea Bass has a unique perspective of what the Audio Fidelity era was like during the period in the 1950’s and 1960’s when her father, Sid Frey, was at the helm.

J.S.: Your father, Sid, was a pretty creative entrepreneur as well as an independent music recording industry maverick. What family history circumstances do you think contributed to this individualistic streak, and why do you think it led to his affinity to music to eventually start Audio Fidelity? Also, what contributions do you think your mother, Rosalind, made for the label?

A.B.: Those are some really good questions. My dad did not have a background in music. He did go to Stuyvesant High School; back in those days, Stuyvesant had a – mechanical bent. His father owned a series of bakeries, and he was a very innovative inventor. He invented a host of labor saving devices for commercial bakeries. I remember my grandmother saying, “The people from Silvercup (a bread brand in New York City whose facilities have now been converted to TV production studios) came in”. So he was very creative.

And his mother, Molly, had an amazing coloratura opera voice, which was never commercialized. She was born in Romania. Her father brought her to the United States when she was 12 years old. She went to live with her sister and raised her four boys. She had some 3-4 years of public school education but never had an opportunity to pursue a career. Very bright; she was a math whiz who could supposedly add up to twenty numbers in her head while working at the bakery. So, the genetic stock was good. (laughs) But no relatives that I can think of who were musicians.

That being said, my dad was in the Merchant Marine during World War II. Part of his travels took him to Brazil, and that, I think, is where he became acquainted with Bossa Nova music. And another part of his legacy is being the first to bring Bossa Nova musicians, artists and songwriters to the US in 1962 for what was a very famous concert at Carnegie Hall. There were some technical problems with the concert, but it’s still considered to be a milestone in terms of the advent of Bossa Nova in the United States.

J.S.: And how about your mother, Rosalind?

A.B.: She was a counterweight to my dad. She was…a very astute stock market investor. When my father started to make money, he told her, “You go figure out how to invest it.” She took all of the correspondence classes at the New York Institute of Finance. She became very good at managing money, and she became a counterweight to him. She was smart, quiet, and unassuming. She was – life was a party, but she could also have a terrible temper. A very volatile person.

JS.: Was Sid Frey’s pioneering work in commercializing stereo recordings something of historical significant awareness to the family at the time? Was it considered just another technical product, like the train effects and other non musical recordings, since Audio Fidelity records wound up being used to demonstrate stereo systems in the industry’s infancy, or was there an awareness of a new market emerging, and why?

A.B: At the time? Well I wasn’t really old enough at the time. But amongst my family members, he was a hero. I mean, it’s a testament to my mother and everyone else who supported my dad, that they stood by him and felt he had the wherewithal to start a company like this. He may have had some entrepreneurial genes, but he had no money and no experience that I know of in the record business.

My grandmother told me that at one point, he was selling neon signs. But then apparently, he connected with a guy who was distributing Israeli records, Jewish records for the Seymour Records series. Stuff like “Hanukkah Music Box” and “Passover Music”. I think, somehow, my father was left holding the bag for Seymour Records.

And he then got the idea to build up the company, and he started with these “Audio Rarities”, which, as far as I know, was free content. He had recordings of Laurence Olivier, recordings of Hitler making speeches, things like how to teach your parakeet to talk…(laughs) It was really…eclectic! And then, somewhere along the line, he got interested in bullfight music. We had relatives in Mexico, so he had travelled to Mexico. I don’t know the whole chronology of his records, but I remember that the bullfight music became a big deal, even before stereo. There were pictures of him in various newspapers recording bullfight music in Mexico with the tape recorders and everything, but it was right in the middle of the grandstand of the bullfight ring! So, he had the wherewithal to pull that off.

I don’t know how he got the stereo idea; maybe he had heard about what Emory Cook and Westrex had been doing, and somehow got it into his head that this was going to be the way to make his mark.

J.S: So it was almost like he was constantly hustling to do all kinds of different things…

A.B.: He was a hustler! And somehow, he came across stereo as an idea and how to pull it off. And he pissed off all the other record labels.

One guy – Robert Angus? Do you know this name? He used to write for either Billboard or Cashbox,[Angus wrote for Billboard in the ‘50s, and later, High Fidelity—Ed.] and he said he was covering the Audio Engineering Society events or at least one event where my dad was introducing stereo. And my dad literally was shouting other people off the stage! (laughs) He was never involved in politics but he had that kind of a personality.

J.S.: What was Audio Fidelity’s relationship with its artist roster like? Any stories or incidents that you can recall which shows the way Sid Frey handled his artists?

A.B.: I’m in touch with some of the descendants of the artists or the artists themselves, at different points in time. For example, the son of one of the guys from the Dukes of Dixieland. He’s like the Keeper of the Flame. I’ve talked to him. And he said that the Dukes of Dixieland really didn’t trust my father! I don’t know how he came up with this, because he offered them lots and lots of money…he wasn’t a big record label, but somehow he convinced them to go along with him. There’s also guy who was also involved but is not alive anymore named Joe Delaney. He was a writer about Las Vegas show business. But he was also involved with managing the Dukes of Dixieland.

J.S.: Well, during that era, artists rarely knew anything about the business side of the music recording industry. I mean, now we know the stories about Sam Phillips and Sun Records or Leonard Chess and Chess Records. And there’s always two sides to the story. In retrospect, yes, the artists get a lot more now than they did back then, but there was no real market yet at that time. I mean, people like Sam Phillips and Sid Frey created the record market for independent label popular music.

A.B.: From what I know, I don’t think my dad had a reputation for cheating his artists. On the Dukes of Dixieland website, there’s a picture of a check for $100,000 from Audio Fidelity Records – an enormous amount!

J.S.: That was real money back in the 1950’s!

A.B.: Right. But of the artists I’ve talked to – they all say, “I didn’t get my royalties.” Like Oscar Brand, Manny Barty… these people are dead now. I tell them, “I can’t do anything about that now. My father died in 1968.” But I’ve met some of these artists. I’ve met Johnny Paleo, Louis Armstrong…the Bossa Nova people…they all came to our house for a party. So I’d say the relationship was pretty good. He had to have a lot of charm to convince these people to make records for him! He was an unknown entity! He certainly wasn’t an established label like RCA! Some of these artists had choices as to whom to record for, and at least for a certain period of time, they chose to be with Audio Fidelity.

J.S.: Continuing on that topic – Lionel Hampton, The Dukes of Dixieland, Al Hirt, Lalo Schifrin, and also recordings of flamenco, bagpipes, pipe organ, harmonicas, marches, Hawaiian music, and Middle Eastern music, among other genres, are all part of the AF catalog releases during Sid Frey’s time at the helm.

A.B.: I worked in consumer products for twenty years. I know what it takes to launch a new product; there’s a lot involved. My dad put out like 600 records in a period of 10 years. He had very few employees. Diane Turman was the head of the PR team and she still is in the field. We’re Facebook friends. But they did a lot to get the records noticed. My dad and she figured out that publicity was the way make his reputation. And they got him tons of news clips!

J.S.: Did Sid or your mother cite any particular favorite records and explain why?

A.B.: No particular favorites when he was alive. Years later, something like Bossa Nova might come on the radio, and my mom would recall, “Oh, daddy recorded that.” My father did have a huge, monster stereo system – there was an article about it in a hi-fi magazine – and he used to play it full blast. We lived in an apartment building, and you couldn’t even hear the doorbell ring, it was so loud! We had soundproofing in the apartment, but it was amazing he was never sued by the neighbors. When he was just playing records in the house, he often played Bossa Nova. Not even necessarily his records, but Bossa Nova in general.

J.S.: Why did Sid Frey sell the label in 1965, and what did he do subsequently after that?

A.B.: The company was taken over by a guy named Herman Gimpel in 1965. There were some rumors…I think he realized that the times were changing and that he wasn’t going to make it in the pop music business. He had artists like the Teemates that were sort of a Beatles type of band. But he saw where the industry was headed, and I think he saw that his time had passed. The music business had some Mafia connections (in New York) and he didn’t want to stay in that circle.

Apart from music, he was also an avid coin collector. Whenever he did something, he went all out and did it to the hilt. He knew this guy named Hans Schulman , who, to this day, has a gigantic reputation in the world of numismatics. Hans Schulman used to come to the apartment – this Mr. Big who sold coin collections to King Farouk of Egypt – and he convinced my father that coin collection was “the hobby for kings”.

He got involved with publishing a catalogue of Chinese coins. Remember, this was the Sixties – before Nixon went to China! He started getting interested in coins while he was still at Audio Fidelity, but got more into it after he retired. I have no real interest in numismatics, but apparently some of them were quite valuable and it turned into as good a long term investment as any other collectible.

I also had a cousin who a techie guy and into CB radio. This was before it got really big in the Seventies. My dad then got a CB radio for the house, and he got one for the car, and he’d be on that thing constantly – talking to strangers…he’d go to the ultimate! I remember being in the car thinking, “Who the hell is he talking to?” But that was another of his hobbies.

J.S.: What do you think is Sid Frey’s greatest achievement and legacy to music recording history, and how do you think he would like to be remembered?

A.B.: There would be no doubt about the fact that he loved being called, “Mr. Stereo.” I don’t know if it he or the PR team that came up with that moniker. And people from the Audio Engineering Society, as of 10-15 years ago, were still hostile towards my father.

J.S.: Hostile?

A.B.: I think they feel that he usurped the introduction of stereo – and he wasn’t the easiest person to get along with. There was a presentation that went into the history of stereo with German tape, and the Emory Cook recordings, and they really downplayed my father’s contributions to the industry. There was also a presentation on the history of recorded sound, and they didn’t even include him!

At one point, I got involved in the AES Historical Society, and became friendly with (the late) Irv Joel, who was a top engineer at Capitol Records. Anyway, he did the research about my dad and gave a very nice segment about Audio Fidelity. But other people were quick to credit Emory Cook for also selling records. It’s kind of like (the debate about) Tesla and Edison. Tesla made many contributions, but he didn’t get the credit, while Edison became the (commercial) kingpin of the industry.

J.S.: As an artist in your own right, how do you think your experience growing up in a music and business environment in NYC has informed your choices of profession?

A.B.: I became an artist after working in marketing for quite a number of years. My family always encouraged all kinds of creative activities. My mother was an oil painter. My sister and I took piano lessons, ballet, went to museums. After deciding to really get into art and studying art history, I now have several mentors in the City College Arts Department that have encouraged my work.

One thing I did learn, and it is somewhat related thematically, is the history of the Barbie doll. Barbie was a very innovative introduction to the American landscape. Before Barbie, all dolls were baby dolls, so girls could pretend to be mothers. This unbelievable entrepreneur, Ruth Handler, was the president of Mattel and created the Barbie doll. In the face of huge opposition, she put out Barbie in the 1950s and it became the best selling toy in the world. Barbie could change her clothes and be a stewardess, an astronaut – this was quite an expansion of the toy industry. It turns out that Ruth was travelling in Europe and got the idea of how the Barbie doll should look because of dolls that were made from a character in a German semi pornographic comic strip. Ruth Handler saw something there that could be modified and marketed on a big scale, just like my dad with stereo.