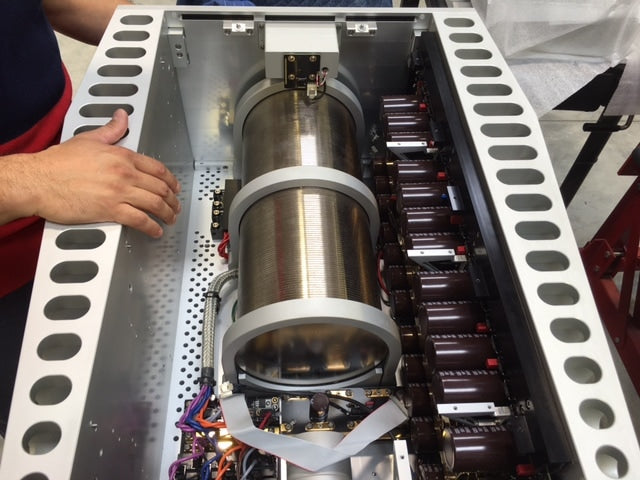

Part II: The coupling capacitors

In the last issue, we discussed some basic theory concerning power supply capacitor replacement in vintage audio gear. I explained that the condition of these capacitors is essential in maintaining performance and reliability. While capacitors used in the power supply can and do influence the sound, they are not nearly as critical compared to when they are used in an application known as signal coupling.

What are coupling capacitors and why are they such a critical factor when it comes to the sound of a component? How do you know when it’s time to replace them? How do you locate them and choose replacements or upgrades? In this article, I’ll answer these questions and walk you through the process of locating and replacing these critical components.

What’s a coupling capacitor?

Coupling capacitors are capacitors used directly in series with the signal path. All musical information that you hear out of the speakers has to travel through them. But why would audio designers place capacitors in the signal path at a risk of compromising the fidelity of our precious music?

In order to understand this, we must look at some basic properties of capacitors. In an ideal world, a capacitor acts like a wire (short circuit) when passing alternating current and a cut wire (an open circuit) for direct current. AC is alternating, meaning that it goes from positive to negative at a given frequency, and DC doesn’t have a frequency at all (0Hz). The important thing to catch here is that music is an AC signal. Ideally, a capacitor should pass all musical signals but block DC from passing.

This is precisely the purpose of a coupling capacitor.

In many amplifiers, the designer has used coupling in order to separately control the DC bias of each gain stage. The isolation between each amplifier results in zero DC offset from the last stage being fed into the next.

Another application is for input protection. For example, imagine an amp with a gain of 30 that has no DC blocking throughout its signal path, and is connected to a pair of speakers. If a preamp upstream becomes faulty and outputs 1V DC on the amp’s input, 30V DC will appear across the terminals of the speaker. This level of DC has the potential to fry woofer voice coils.

Don’t ask me how I know that.

Finally, many preamps that use a single output device running in class A use coupling caps on the output. The DC voltage that’s present due to the idle biasing conditions must be blocked and only pass the audio signal. For instance, most preamps that use vacuum tubes as the output device have an output coupling capacitor.

What determines the value and type of a coupling capacitor?

The circuit A shown in the figure below is an example of a coupling capacitor that is used on the input of a simple transistor voltage gain stage. The circuit can be simplified by modeling the input impedance of the amplifier with a single resistor. The resulting circuit on the right forms what is called a high pass filter.

A high pass filter is exactly what it sounds like; a filter that attenuates low frequencies and passes the high frequencies. The cutoff frequency in which there is a 3db attenuation of low frequencies is found by fc = 1/(2*pi*RC). Since we want to avoid phase distortion and attenuation of the lower frequencies, we want this cutoff frequency to be as close to DC as possible.

For example, if the input impedance to the stage is 100 KOhms and the input capacitor is 2uF, the product of R and C would equal .2 seconds. Plugging the RC product into the cutoff frequency equations tells us that at .8 Hz, bass frequencies will be rolled off by 3dB. Since we know that the human ear can only hear down to 20 Hz, this cutoff frequency would be adequate to hear the lowest notes in music without attenuation.

In many older designs, the only capacitor type that was practical given the cost, space, and value were electrolytic types. As we discussed in the previous issue, electrolytics degrade over time by changing value and increasing parasitic properties. As the value drops, the cutoff frequency goes up, rolling off the bass frequencies and introducing phase distortion within the audio band.

Although electrolytics were prevalent in older designs, they are not the only capacitor type that you will find. Even today, many high-end designs use plastic film capacitors as coupling capacitors. Film capacitors are superior to electrolytics and as a result sound much more transparent. Unfortunately, not all designs use these due to their cost, size, and lack of high capacitance values.

How do you know when it’s time to replace the coupling capacitors?

In the case of electrolytics, many environmental factors determine the lifetime of the component. These factors can range from the temperature at which the capacitor was operating at to the amount of voltage that was applied to it. Electrolytics as new as 10 years old can start to show symptoms of aging. If your component is 10-20 years old and you are suspicious that the sound quality has diminished, the coupling caps are likely the first place to look. If it’s older than 20 years, I wouldn’t even hesitate.

Plastic film capacitors are a different story. For the most part, they do not display dramatic symptoms of aging. Despite this, there are several reasons why I would recommend still changing older films.

Firstly, it gives you a chance to “upgrade” the component and purchase a better capacitor that perhaps the manufacture couldn’t afford to include in the original design. Cap technology has also advanced over the years and it’s likely that modern capacitors will sound better than their older counterparts.

The final motivating factor is an exciting one. Changing capacitors allows one to tune a component to his or her subjective preferences. Many favor doing this instead of constantly changing amps or preamps in hopes to just blindly stumble across something that works for them. Those who master this have some of the most synergetic and cohesive systems that I’ve heard…and they’re having fun doing it!

How do you identify signal path capacitors and choose replacements?

Similar to when we discussed changing the power supply capacitors in part 1, the first step is to acquire the schematic to the component you are working on. Below is a typical signal path of an older solid-state gain stage.

The input of the amplifier is notated on the left with a 1. Following the signal path from the left to the right, it’s clear that C3 is in series with the input. This is our input coupling capacitor. Noticing that the value here is very low, I would highly suggest to use a plastic film capacitor in this location best sound quality.

Following the remaining of the signal path which is highlighted by the bolder line, we discover C9. C9 is the output capacitor to this stage. It being 10uF’s limits us because it’s unlikely that a film of this value would fit on the PCB. For this reason, an electrolytic from Elna, Panasonic, or Nichicon will do the trick. Similar to the power supply caps, increasing the voltage rating so that it fits the PCB footprint is completely fine.

Here’s a little tip: you can help reduce the coloration that C9 inflicts on the sound by bypassing it with a small film cap (.1-.47uF). Tack the film under the PCB so that it’s in parallel with the electrolytic. Experiment with different types and see what you prefer.

If you noticed, we forgot about two other capacitors. These caps are actually not being used for a signal coupling application. Instead, C11 is used as what is called an emitter bypass capacitor. This capacitor allows the designer to DC bias the stage without compromising the AC gain of the amplifier. If this capacitor decreases in value it will cause degeneration at lower frequency, which in turn will roll off bass frequencies. For this reason, we also want to replace this capacitor.

The final capacitor, C7, is what is referred to as a feedback compensation capacitor. These are indeed very audible and the low value gives us plenty of options. I recommend a high quality plastic film type such as polypropylene, polystyrene, or silver mica. Never change this capacitance value as it was selected by the designer to optimize the stability and high frequency distortion performance of the amplifier.

As for the type, it’s for you and your ears to decide. That is what’s beautiful and exciting about DIY.

Warning!

I am sure you have heard the dangers of working on electronics. My advice to you is to read up on how to be safe when working on equipment. While working inside of electronics, always treat everything like it has the potential to kill you. Make sure the AC cord is unplugged and discharge all power supply capacitors before you start working. This reinforces correct habits and may very well save your life.

If not clearly marked, always notate the correct polarities on the PCB before removing any electrolytic capacitors. If electrolytics are reversed, they could explode and cause severe injury. Please be cautious!

Below are links to information to learn about proper safety practices.

Safety links:

-

General Safety Information:

http://www.diyaudio.com/forums/showwiki.php?titleIYSafety

-

How to discharge a capacitor:

http://www.learningaboutelectronics.com/Articles/How-to-discharge-a-capacitor

-

How to make a capacitor discharge tool:

https://www.ifixit.com/Guide/Constructing+a+Capacitor+Discharge+Tool/2177

Links to popular capacitor vendors:

Capacitor reviews:

http://www.humblehomemadehifi.com/Cap.html

http://www.laventure.net/tourist/caps.htm