That evening, I related to Melody’s family the story of the interesting dialogue I’d heard from the senior citizens on the beach.

Melody’s brother started laughing. “You don’t think they’re here to fish, do you?”

I looked at him with a jaundiced eye.

“They’re here to get drunk, man!”

“I don’t think so. Most of them had no alcohol, and the three that did were nowhere near drunk. To the contrary, they were more lucid than most people I meet.”

“I agree,” Melody’s dad interjected; “I’ve overheard some of their conversations and they are compelling. We can learn a lot from people who’ve been around for a while.”

That shut Melody’s brother up.

“Tomorrow’s the last day of the rally and there’ll be many riders going by here, so I’m going to open the saloon again. I want you behind the bar,” Dad said to his son.

“Can’t do it dad; if I don’t get those tomatoes harvested, they’ll be too soft to ship.”

”Well, I don’t want to put Melody back there and risk another incident.”

“I’ll be happy to help,” I interjected. “What hours will you be open?”

“Really, Montana! That would be great. I’m thinking noon to 6 PM, does that work for you?”

“No problem; I’ll ride to Spearfish in the morning, pack up my campsite, and be back here by noon.”

Melody and her mother smiled.

Melody’s brother took me on a tour of his greenhouses after dinner. They must have been 100 feet long with thousands of plants in neat rows on tables served by sophisticated irrigation, lighting, temperature, and fertilization systems. He’d studied agriculture in college and was well-versed in modern methods of intensive farming.

“I’m the first to institute greenhouse market gardening in South Dakota,” he said. “No one thought it was possible in this climate, but I’ve proven that with the right equipment, we can get three organic crops per year instead of one.”

I made no secret of the fact that I was impressed, but not as much by the greenhouses as with the fact that he had found his calling. Young men often get into trouble not because they are bad people with evil intent, but because they are adrift and don’t know what to do with themselves.

When I worked as a probation officer, I often talked clients into taking the Strong/Campbell Interest Inventory, a personality assessment analysis that compares their personalities to those of successful people in different fields. It was a great tool to steer them in a direction which fit their personalities, far more effective than referring everyone to an academic institution. (People who aren’t suited to that environment usually fail, further denigrating their self-image.) Many of these guys ended up taking apprenticeships in various trades, and years later often made more money than their academic counterparts. Not only that, they were happier because they were doing what they loved, just like Melody’s brother.

It was late by the time I got back to my cabin. Melody didn’t show.

After breakfast the next morning, I rode to Spearfish to pick up my gear. The Harleys on the road were loaded with luggage and heading home. I was again captivated by the scenery. Many parts of the Black Hills look like a manicured theme park. The huge stones are neatly and deliberately placed to give the scene a balanced presentation. The trees were carefully selected for their aesthetic properties and sized just right to complement the stones. I couldn’t help but stop at several overlooks to admire the landscaping and take photos. One of them offered a specular view over the sun-blasted badlands.

When I arrived at Spearfish City Campground, many riders were packing up, including my friends Bert and Roland. We sat down at the picnic table for a while and exchanged pleasantries.

“Some of the finest riding roads in America are in the Ozarks,” Roland piped up, “and I’m going to be Bert’s tour guide.”

“That’s great, Roland, you guys will have a fine time. This your first time to the Ozarks, Bert?”

“I’ve ridden by them but I’ve never explored them. You can come with us if you like, Montana.”

“Tempting offer Bert, but I’ve made other plans.”

“Oh, that reminds me,” he said. “There’s another message for you on the bulletin board.”

Bert insisted again on giving me some money for letting him stay on my campsite, but I refused.

“What you taught me about beating disease has had a profound influence on me, Bert?” I said. “We don’t have to be dependent on doctors if we take responsibility for our own health. That knowledge is worth more than anything else you can give me, and I’ll be forever grateful.” He smiled.

Candy’s note on the bulletin board read, “Greetings Montana, the boys are getting together on Monday evening to share Sturgis stories and photos. The ride’s about nine hours on a Harley, but I’ll bet you can do it in seven. Please join us? You can stay at our place for as long as you like.” She left a phone number.

I took the note down from the board and put it in my pocket.

“You going to Minneapolis then, Montana?” Bert asked.

“After two invitations, I guess I don’t have much choice.”

We packed our gear and swapped contact info. I gave him a hug before we took our leave. He clearly wasn’t used to that but, somehow, I knew this would be the last time I’d ever see him.

When I got back to the trout pond, Melody’s mother was cleaning the cabins. I asked her if and when I could use the machines to do my laundry.

“I’m washing right now,” she responded. “Just throw your stuff in this pillowcase and I’ll do it.”

I went back to my cabin and a few minutes later came out in shorts and my last T-shirt along with a pillowcase stuffed with laundry.

“Throw it in the bin Montana; I’ll take care of it.”

“I really appreciate that.”

Melody’s mom was a hard worker who took her responsibilities seriously.

“Lot of work running a place like this, huh?” I asked.

“Not as hard as teaching school,” she responded, “and a lot less stress. I love it here. I’m glad we raised our kids here, they both turned out well. I couldn’t be more pleased.”

Why do self-employed people always seem happier than those working for others, I asked myself, even if they work twice as long and twice as hard?

I went back to my cabin and looked over the papers I’d pulled out of my jeans. I ripped up all the credit card receipts and came across a paper I didn’t recognize. It was titled, “The Bhagwan’s 10 Commandments for a New Era.” Ah yes, the paper his female assistant gave me as we left the Airstream. It was just before noon so I didn’t have time to read it before rushing off to the saloon; I arrived just as Melody and her dad were unlocking the front door.

He started to give me instructions for operating the bar, but Melody interjected.

“I’ll take over from here, dad.”

“Thanks Melody, I’ll leave it to you.”

“Why don’t you move your bike around to the front of the building, Montana, and maybe it’ll entice some other bikers?” she requested.

As I followed her suggestion, I waved to the seniors on the shore of the fishing pond. They waved back, signaling me over.

“No time,” I hollered, “got to work the bar.” They waved me on.

Melody explained how to work the cash register and where everything was located, including a pot of coffee brewing next to the fridge.

“I’ll make breakfasts and burgers in the building next door,” she said.

“Got it…I missed you last night.”

“We’re two ships sailing past each other in the night, Montana. Tomorrow you’ll be gone and I’ll be preparing to go back to school.”

“Will you be visiting the Bhagwan again on Friday?”

“Oh yes; he’ll be out-of-state next month so he’s hosting only two more Friday session this summer. If you’re in the area you’re welcome to join me.”

I determined to do just that.

A red pickup truck pulled in front of the bar. “Ah, it’s Lonnie Many Bears!” Melody exclaimed.

Lonnie wore long, braided hair and a headband with Native American symbols, a deerskin jacket, and an amulet around his neck. The guy with him was dressed like a typical college student.

“Who are they?” I asked.

Lonnie is a Lakota chief who lectures on Native American studies in my school,” she responded. “He lives near here and likes to drop by on Saturdays. Until he turned 50, he spent a month every winter in the mountains by himself with nothing but a sleeping bag, a tarp, a knife, and some basic necessities.”

“What did he live on?”

“He snared small game. According to native tradition, there’s lots of other edible things in the woods to eat.”

“How did he keep from freezing at night?”

“He used the tarp to build a lean-to and would build a fire each evening at the open end.”

When they walked through the door, Melody ran up and gave him a big hug.

They sat down at the bar and Melody introduced us: “This is Lonnie.”

“This is Richard, my grandson,” Lonnie said. “He just graduated from college.”

I smiled and shook their hands.

“The usual, Lonnie?” Melody asked. He nodded.

“I’ll have the same,” Richard requested.

“OK, two eggs over easy with ham and toast. I’ll be right back.”

As she was leaving, I asked them if they wanted anything to drink.

“Just coffee,” they responded, and began talking to one another.

“As I was saying in the truck, Grandpa, if all the native American tribes had pooled their forces to repel the advance of the Europeans, they’d never have gained a foothold in the Americas.”

“If all the Africans had done the same thing, they wouldn’t have been colonized,” Grandpa responded, “but those tribes had been fighting for centuries for control of resources. They were bitter enemies. No one could have convinced them to drop their hostilities for a threat they didn’t understand.”

“Don’t you see, Grandpa, it was those hostilities that made it so easy for Europeans to divide and conquer.”

“So what are you saying Richard, that it was our fault that the West was lost?”

“Right, we didn’t engage them effectively.”

“They outnumbered us badly Richard; we didn’t stand a chance.”

“That was true in the 19th century, Grandpa, but before that, we could easily have defended our lands with a unified response.”

“Woulda, shoulda, coulda, Richard, everyone’s got 20/20 hindsight. You have to remember that the Spanish decimated most of the native population with disease.”

“That was a crime against humanity.” Richard responded.

“An inadvertent crime against humanity; nobody knew anything about viruses or bacteria back then. The native population didn’t connect it to the Europeans. Most of the victims had never even seen one. They saw disease as a foreboding omen from the Great Spirit.”

“Stupid.”

“No, it was superstition. Superstitious people are easily scared.”

“Still, I wish they’d fought as a united force.”

“A draped horse carrying a Spanish cavalry rider clad in gleaming steel armor must have seemed like a monster from outer space to people who had never seen horses. When they observed that it could outrun a buffalo and kill braves with a stick that spewed lightning and thunder, they must have been astonished. Hundreds of them in formation must have seemed like an attack from the forces of hell. Who could know what other powers those devils had?

As virtually unarmed, un-armored, and unorganized foot soldiers, our braves would have been easy to intimidate, demoralize, and route, even if they were a united force. It was smarter for them to capitulate in hopes of the tribe being spared.”

“I suppose that would have been the logical thing to do, Grandpa.”

“Of course it was, our ancestors weren’t fools.”

“Sad story nonetheless.”

“Like it or not, the entire history of the world is a series of sad stories, Richard – one culture overrunning another. Ever read the Bible? The world has always been governed by the aggressive use of force. Many American tribes were wiped out by other natives tribes long before Columbus arrived. This happened over and over again to every culture on every continent of the world. What the Europeans did to us was nothing new or unique, they’d been doing it to each other for thousands of years. Why do you think they built all those castles and fortresses? Why do you think we have cliff dwellings in the Southwest?”

“I’d never thought of it that way.”

“To hold a grudge on this account will not improve your life.

“So, I should forget my heritage?”

“Of course not, you should honor your heritage, and insist that others do as well, but you can’t move forward by looking in the rearview mirror. I’ve seen other young men like yourself consumed with hate for what Europeans did in the past. What did it get them? Nothing but miserable, self-destructive lives on the reservation.

The irony is, most European-Americans are descended from people who immigrated here after the year 1900. Their ancestors played no part in the Trail of Tears, slavery, or American history. Why should Native Americans hate them? The fact is, their ancestors came to America to escape similar injustices in their home country. The enemy is not whites, the enemy is tyranny.

“I understand Grandpa, thank you for that. So, what can I do for my people?”

“Here’s what you can do. First ask yourself, ‘Is my life better or worse than that of my ancestors?’ If you answer honestly, you’ll find that in virtually every respect, it’s better, longer, healthier, happier, and presents more opportunities than were ever available to us in the past. That’s your contemporary legacy Richard; you just have to decide what to do with it.

I want you to prove that the Lakota can do anything as well as anyone else in America. If you can demonstrate that to the other kids in the tribe, you’ll have done a greater service than any Indian activist.”

With that, Lonnie Many Bears transferred an amulet from around his neck to his grandson’s neck.

“But never forget your heritage.”

I saw tears well up in Richard’s eyes.

Melody came through the door at just the right time to lighten the mood.

“All right then, here we go, two orders of ham and eggs with toast,” Melody exclaimed cheerily as she set two plates on the counter in front of the men, “Need any sauces or spices?”

Richard requested salsa.

[Note: this installment was written prior to the current situation in the Ukraine – Ed.]

Previous installments appeared in Issues 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156 and 157.

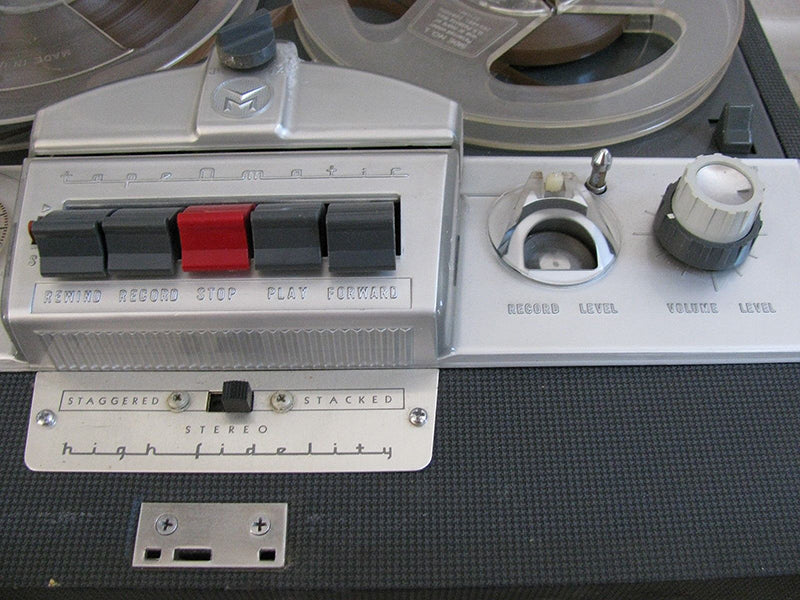

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Hiart.