[The first installments of this series appeared in Issues 143, 144, 145, 146, 147 and 148 – Ed.]

The next morning, I awoke to the sounds of clattering tent poles. Unzipping my tent door, I was surprised to find that many of the renegades were packing up.

Others were sitting at the picnic table. Candy looked my way and explained, “They’re so bummed about the loss of Red that they don’t think they can enjoy the rest of bike week, so they’ve decided to ride home.”

She was consoling one of the other girls. Candy was always there when needed.

When the packing was done, everyone crowded ’round the table and Chip spoke up. “I’m just as upset about Red as those who are leaving, but I can’t do anything to reverse it, and I’m not going to let this ruin my trip. If you feel the same way, you can enjoy the rest of bike week with us and we’ll deal with our grief when we get home. I’ll organize a wake to give us some closure.

But if you feel the need to grieve now, you’re better off riding home with the others.”

This forced the renegades to make a decision, and most chose to leave with the rest of the group — including Gimp and Tina in the ugly school bus.

Chip, Candy, Spider, KP, and I stayed seated at the picnic table as we watched them pack. Candy ran to town for some coffee. We saw the guys whose bikes had been destroyed by the fallen branch get on their rental bikes and ride out for the day. City crews were removing the balance of the tree. Other riders rode by on their way to enjoy the day’s adventures. The trash truck made a ferocious racket emptying dumpsters. Spider and KP got up to help Gimp load his trike into the back of the ugly school bus. Campers strolled by and nodded on the way into Spearfish for breakfast. A couple of cops on Harleys cruised around to keep the peace. We waved at everyone, but said little.

Before finally departing, the renegades hugged each other, many with tears in their eyes. I felt a sense of loss as I watched them ride away.

Chip uttered, “let’s go have some breakfast.” We walked to town and sat down on the balcony of the same restaurant where we were the day before. Guys were still drag racing on the main street and girls still walked by barely clothed. The world went on without acknowledging the loss of Red.

After we ordered from the menu, Candy spoke up. “Like Red, I haven’t had a good upbringing, but that didn’t cause me to live in a bad headspace, and I’m certainly not self-destructive.”

“Nature has blessed you with a gorgeous appearance,” Chip responded; “You are treated differently than those who are plain. People will always rush to your defense and you’ll always be given the benefit of the doubt – even if you make foolish mistakes and errors in judgment. Others don’t have that advantage, and as a result, they see the world as more hostile. I’m sure Red did.”

“Where do you come up with these insights, Chip?” I inquired.

“My mother was an attractive woman before she got MS. I saw how other people looked at her in public before and after.”

I was disgusted by their ignorance and disdain, but she took it all in stride. When I asked her about it, she told me this story:

“Inside every mind lives a black dog and a white dog. The black dog is controlled by fear, so it is always barking and snapping at people. As a result, it lives a lonely, miserable life locked up in the back yard. The white dog is motivated by love, it has the courage to approach everyone with a wagging tail and a friendly demeanor. In return, it gets lots of love and attention and lives a satisfying, fulfilling life.”

When I asked her which dog will control my life, she responded, “Whichever one you feed.”

Those words have guided me ever since.

“That’s beautiful,” Spider commented, “but you have a way of causing people to park their black dogs and ride only the white ones. How do you do that?”

Chip smiled. “The more black dogs you tolerate, the more black dogs you get.”

“Easy for you to say, you’re a big dude,” Spider retorted. “That attitude won’t work for a guy my size.”

“Really, Spider! Get up and walk to the door!” Chip demanded with authority. Spider rose hesitantly, walked to the door, then back to the table. “You don’t have to be a tough guy to do that. If you want to avoid black dogs, you just have to have the courage to walk away.”

KP nodded in agreement.

“Red never had that courage,” Chip asserted, “He absorbed the black dogs in others, which fortified the one inside of him. When it got big enough, it consumed his white dog. He hated himself for allowing that. I warned him that it would consume him too if he didn’t do anything about it, but I might as well have been talking to the picnic table.

“That’s why he never responded to love and attention, “Candy opined, “he felt he didn’t deserve it.”

“Red tried to hide his self-contempt through swearing and bravado – which is just another way of barking.” Chip continued, “He didn’t die from tragic circumstances, he was trying to prove to himself and others that he wasn’t a coward. In the process, his black dog consumed three lives. I’m having a hard time crying over his loss.”

A dark cloud of silence descended over the group. I was blown away by Chip’s analysis and his ability to explain sophisticated concepts in simple terms.

The restaurant filled up with bikers as we were waiting for our breakfast. Most of them were in a better mood than we were.

A short, heavy waitress brought our meals with a big smile. “You kids are going to love our country breakfasts,” she proclaimed, “made with love and care.” She leaned over to Chip and whispered, “sometimes they’re free if you agree to go out with the waitress.”

“Really?” Chip smiled.

“Not always,” she responded, “but it’s worth a shot.”

Everyone broke out laughing.

“You’re in a good mood today?” I observed.

“I’m in a good mood every day, Honey,” she responded; “there’s plenty of grief to go around without me adding to it.”

Everyone laughed again – I wondered if she realized how much power she’d wielded that day.

Afterwards, we took a stroll down the main street. This never gets old as there is always something to see.

In front of a service station, two guys were bracing a Shovelhead as a third kicked a jug with the flat of his boot. He put everything he had into dislodging the jug from the crankcase. They told me they were disassembling the engine to replace a broken rod. This was my first experience with the kick-start method of engine disassembly.

Diagonally across the street, a biker babe was using a similar method to tune-up her boyfriend. From the hollering, I surmised that he’d dislodged the wrong jugs the night prior. The sheriff’s deputies were watching the scene from a distance – ready to step in if things got out of hand.

We talked to a couple at the car wash who were cleaning a truckload of mud from their Electra Glide. That revealed a thousand nicks and dents in the paint. We asked about it as their bike didn’t seem that old. They told us that they’d just returned from a trip to Alaska, and that rock-spewing semis up there don’t slow down for motorcycles – or anything else. The guy showed us some bent cooling fins. The woman showed us a nasty bruise on her leg. I decided Alaska wasn’t in my future (I was wrong).

When we got back to camp, Chip determined that Mount Rushmore would make a nice destination for the day. We packed some gear and headed out. Candy rode behind Chip, I rode Spider’s Low Rider, and Spider rode “bitch” behind KP.

The wooded, mountain roads were narrow, twisty, and scenic as they ascended into the hills, perfect for a lugger like the Harley. I plunked it into third and rode it like an automatic.

We stopped frequently to enjoy scenes from the overlooks. That invariably led to discussions with other riders doing the same thing. I was surprised how many of them were from Germany. They looked more badass than the Americans – seems they love this outlaw biker thing. Perhaps it was a refreshing break from their over-regulated, over-monitored society.

KP and Spider argued about riding styles, Spider seemed concerned about his safety. KP told him to get off and walk if he wasn’t enjoying the ride. “I’ve been riding the same way for 20 years Dude, ain’t never dropped it. Can you say that?” (Ouch!)

I considered letting Spider have his Low Rider back and getting on behind KP, but on further reflection, naw. Spider wrecked my bike, he deserved this.

We came across an accident, which was particularly disturbing after the events of the previous day. Emergency personnel were already on the scene so we didn’t tarry.

When KP’s bike developed a carburetion glitch, we pulled over at the next scenic overlook to change a jet. The sound of wrenches clanking on the pavement drew other riders like free beer. Everyone offered advice about how to do it right, and a horror story about doing it wrong. One guy brought us a kit of about 30 jets neatly labelled and arranged on red foam inside a clear plastic box – he was German.

I walked to the edge of the parking area where Chip and Candy were sitting on a rock enjoying the scenery. A highway snaked through the trees in the valley below, and a pond was visible beyond that. Gophers were begging at our feet, and hawks were cruising for them in the air. No one said anything; we just sat there drinking in the scene. Then Spider came over to tell us KP’s carb adjustment was done.

“Sit down and have a beer Spider, enjoy the view for a while,” Chip suggested. Soon, KP joined us as well. He started to chat with Candy, but she motioned him to cease and desist, so we just sat there drinking in the scene while an endless parade of Harleys rumbled by on the highway. It was a transcendental moment.

Until the German with the carb jets sauntered over and babbled, “Dis is besser dan Time Skware, yah?”Chip rose and dictated, “We’re leaving.”

Confused, the German shrugged, “Was ist los?”

Candy responded, “It’s not you; we were just getting ready to leave.”

Editor’s Note: we are aware that “gimp” can have a derogatory meaning and mean no insult to anyone disabled. In the story, the person with that nickname doesn’t consider it as such, and we present the story in that context.

Header image courtesy of sturgismotorcyclerally.com.

Sound pressure level vs. distance. From the

Sound pressure level vs. distance. From the

Amazon Echo, one of a number of devices that is compatible with the Amazon Music Unlimited Single Device Plan.

Amazon Echo, one of a number of devices that is compatible with the Amazon Music Unlimited Single Device Plan.

A Zion Primera guitar, similar to the custom Phil Keaggy model, of which only 10 were made. From the

A Zion Primera guitar, similar to the custom Phil Keaggy model, of which only 10 were made. From the

Alicia Jo Straka

Alicia Jo Straka

Jessica Carson of Clandestine Amigo.

Jessica Carson of Clandestine Amigo.

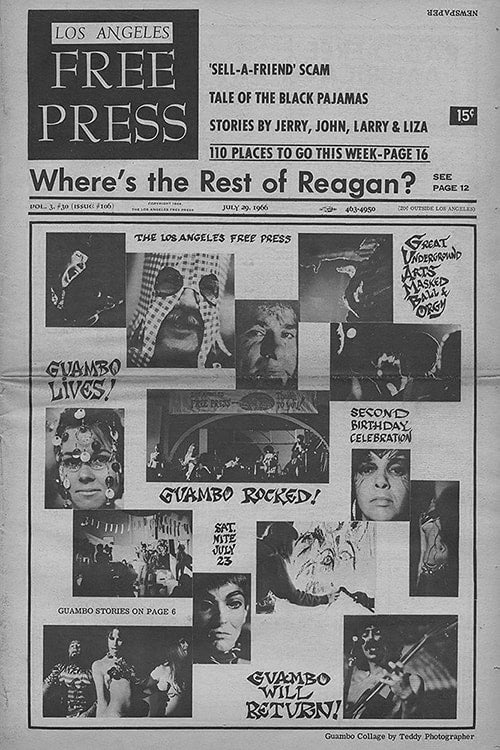

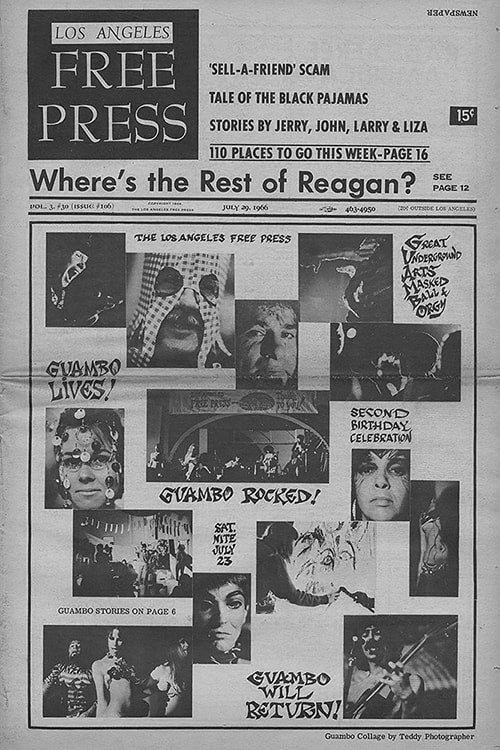

Art Kunkin, founder of the Los Angeles Free Press.

Art Kunkin, founder of the Los Angeles Free Press.

A 1955 Plymouth Savoy like the one Ken rode in to go to the 1969 Northern California Folk-Rock Festival. Courtesy of

A 1955 Plymouth Savoy like the one Ken rode in to go to the 1969 Northern California Folk-Rock Festival. Courtesy of  Northern California Folk-Rock Festival poster, 1969.

Northern California Folk-Rock Festival poster, 1969.

Courtesy of

Courtesy of

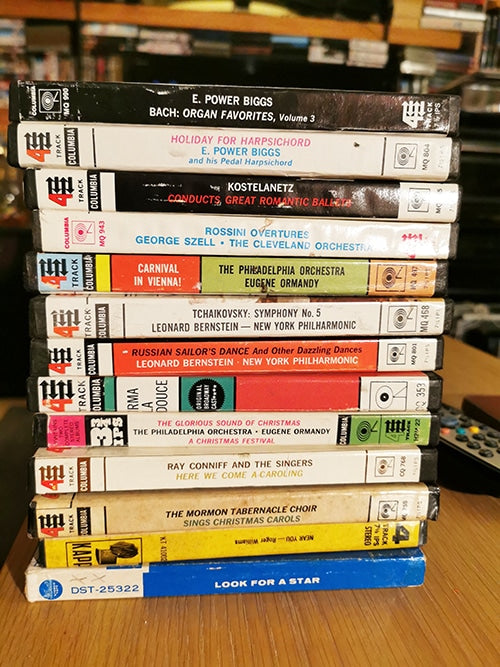

Dynaco/B&O pickup arm.

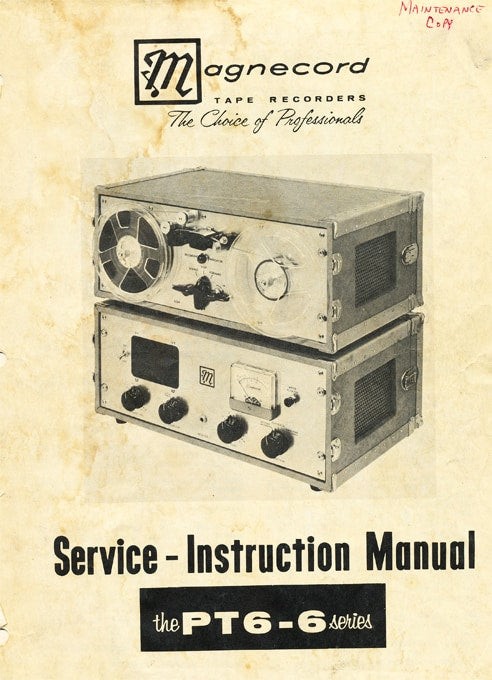

Dynaco/B&O pickup arm. Magnecord PT-6 service and instruction manual.

Magnecord PT-6 service and instruction manual.

DMM Dubplate, Vol. 1.

DMM Dubplate, Vol. 1.

XTC, Go 2, front and back album covers.

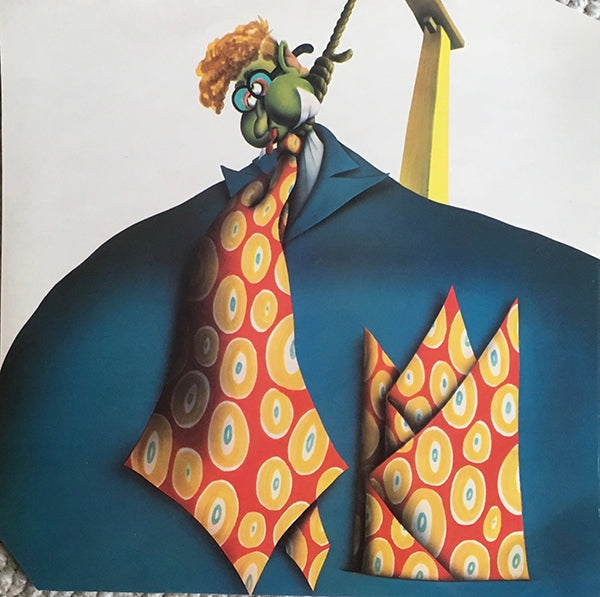

XTC, Go 2, front and back album covers. Alice Cooper, Billion Dollar Babies album cover.

Alice Cooper, Billion Dollar Babies album cover. Billion Dollar Babies inside cover.

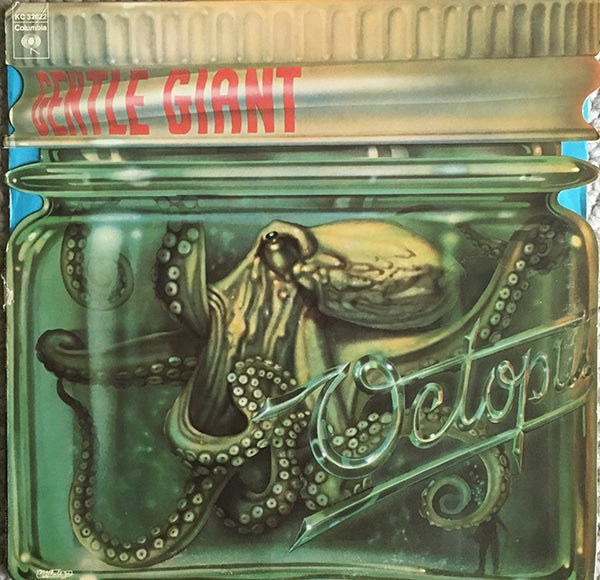

Billion Dollar Babies inside cover. Gentle Giant, Octopus, US album cover.

Gentle Giant, Octopus, US album cover.

Horslips, Happy to Meet…Sorry to Part, front and back album covers.

Horslips, Happy to Meet…Sorry to Part, front and back album covers.

Monty Python, Matching Tie and Handkerchief, front cover and insert.

Monty Python, Matching Tie and Handkerchief, front cover and insert. Todd Rundgren, A Wizard, A True Star album cover.

Todd Rundgren, A Wizard, A True Star album cover. Poster insert for Todd album.

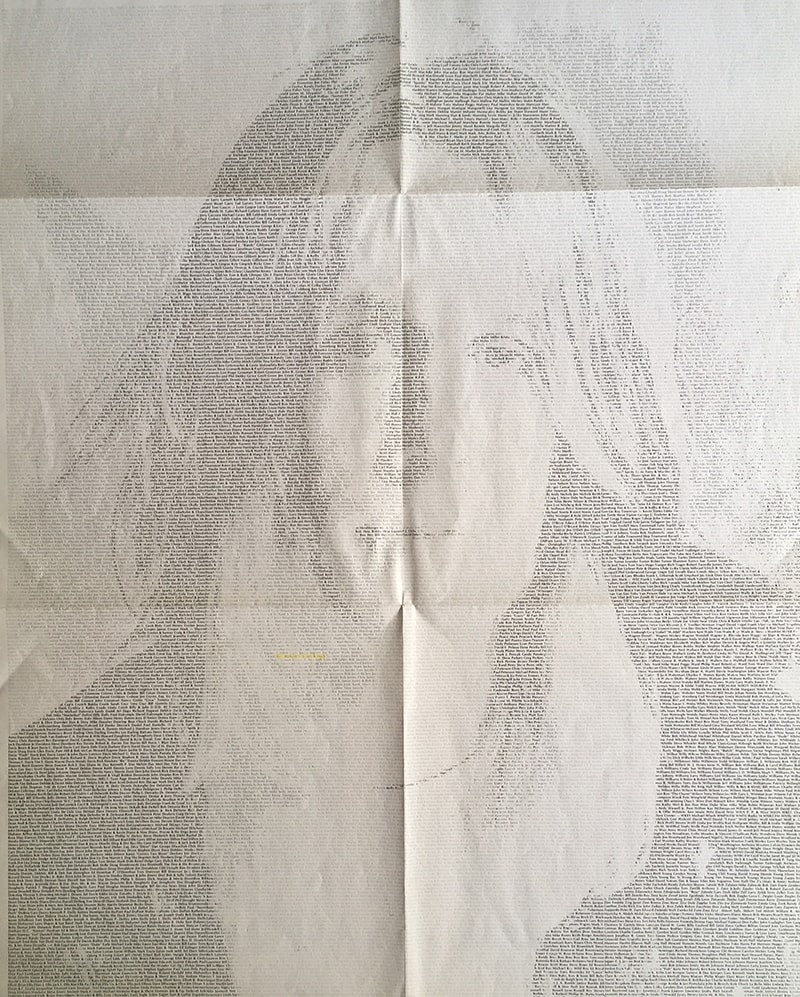

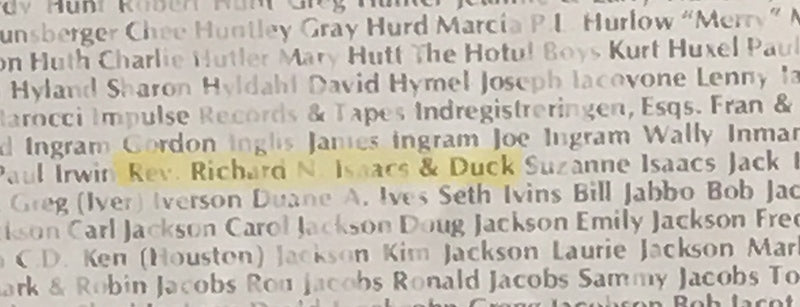

Poster insert for Todd album. Immortalized!

Immortalized!

The Small Faces, Ogdens' Nut Gone Flake, front and back album covers.

The Small Faces, Ogdens' Nut Gone Flake, front and back album covers.

Traffic, The low spark of high heeled boys, front and back album covers.

Traffic, The low spark of high heeled boys, front and back album covers. Kevin Ayers, The Confessions of Dr. Dream and other stories album cover.

Kevin Ayers, The Confessions of Dr. Dream and other stories album cover.

Robert Calvert, Captain Lockheed and the Starfighters, front and back album covers.

Robert Calvert, Captain Lockheed and the Starfighters, front and back album covers. Kraftwerk, Ralf and Florian album cover.

Kraftwerk, Ralf and Florian album cover.

Allsorts, front and back album covers.

Allsorts, front and back album covers.

The Russian Tea Room, a favored hangout of Carnegie Hall attendees, in 2009. Courtesy of

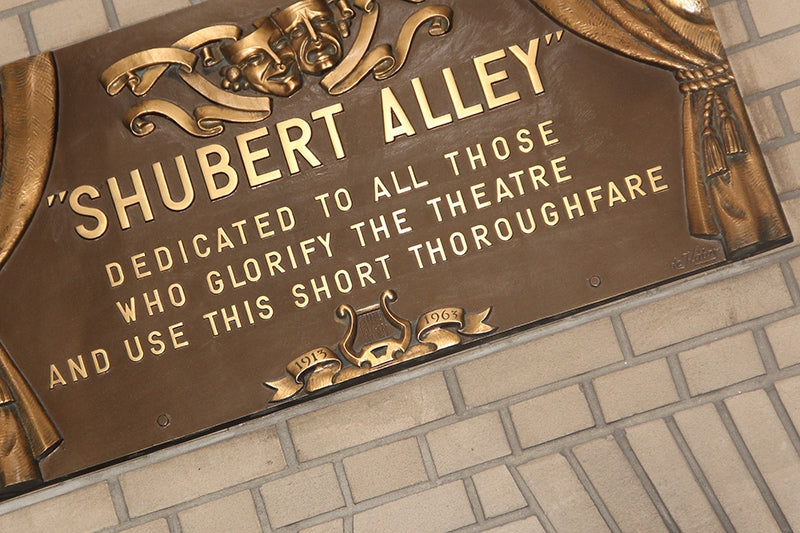

The Russian Tea Room, a favored hangout of Carnegie Hall attendees, in 2009. Courtesy of  Shubert Alley plaque. Courtesy of

Shubert Alley plaque. Courtesy of

Gary Richrath. Photo courtesy of Brad Magon.

Gary Richrath. Photo courtesy of Brad Magon. Michael Jahnz and Gary Richrath. Photo courtesy of Richrath Project 3:13.

Michael Jahnz and Gary Richrath. Photo courtesy of Richrath Project 3:13. Richrath Project 3:13. Photo courtesy of Anne Keuler.

Richrath Project 3:13. Photo courtesy of Anne Keuler.

The AudioEngine

The AudioEngine  My Euphony

My Euphony  The Fiio

The Fiio  How am I supposed to walk away from turntables, tubes, and impressive Class D amplification?

How am I supposed to walk away from turntables, tubes, and impressive Class D amplification?