...and a podcast announcement. I now have a podcast called “The Jay Jay French Connection: Beyond the Music,” available on the Spotify, Apple Music and PodcastOne platforms. On a recent segment my guests were Michael Fremer (Stereophile) and Ken Kessler (Hi-Fi News & Record Review).Those of you who read this column should know both names.

You also can probably guess that they have very strong opinions about all things hi-fi related. Listen and enjoy!

Click here to listen to Part One.

Click here to listen to Part Two.

The last house I was able to visit (i.e. the last social engagement prior to the pandemic’s shutdown of all outside, non-very-close family members’) was a visit to Michael Fremer’s house.

At that first visit, Michael was in the middle of his review of the Von Schweikert ULTRA 9 loudspeakers and the Valve Amplification Company (VAC) Statement 452 iQ Musicbloc power amps. To say I was blown away by the totality of the entire experience would be an understatement.

Not just the gear.

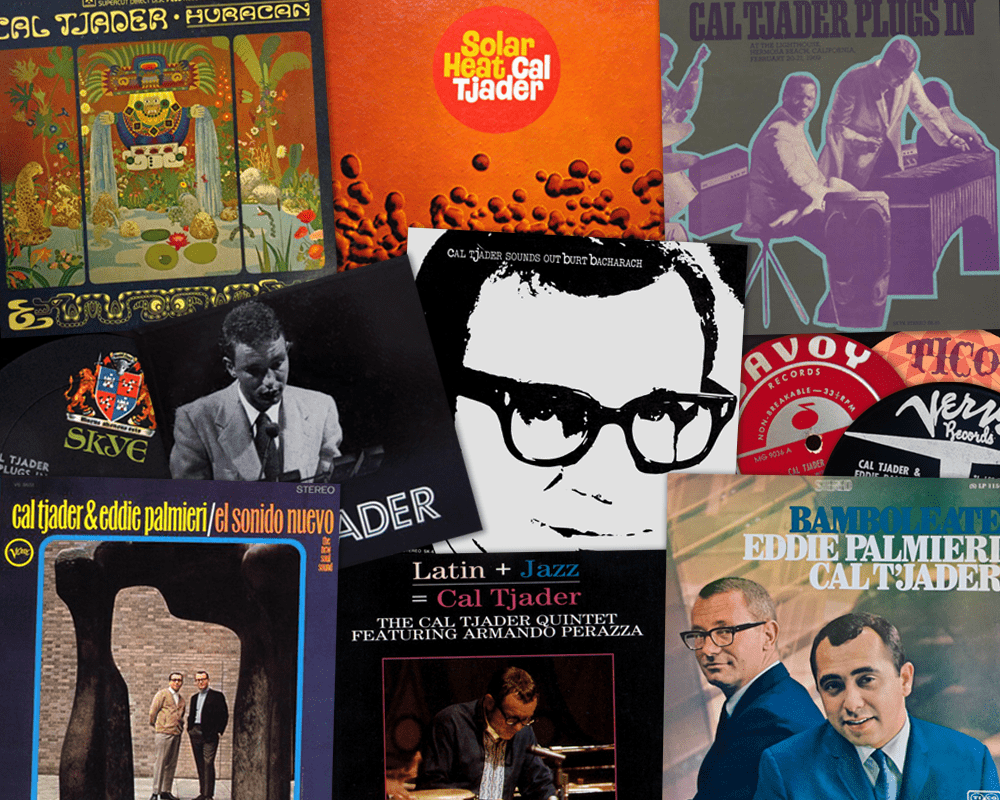

Michael’s record collection was like mine but on the most powerful steroids currently available. Thousands of albums to choose from. At the time, I listened to Michael’s long-time reference turntable, The Continuum Caliburn. So much to take in. Overwhelming.

I thought about that visit during the subsequent pandemic shutdown as I was listening to my not-modest system.

I did spend a lot of time during the lockdown listening to my system and its variety of sources (vinyl, disc and streaming).

I even refined my system during this time, at least the digital side. I got a PS Audio PerfectWave SACD Transport and PerfectWave DirectStream DAC with the Bridge II network connection option. I had lots of time to experiment with power cords, interconnects and Ethernet cables. Yes, they all sound different. Not necessarily better, but different in how the music was presented. This is what is fun about this hobby.

I pretty much have the system where I want it now. (Famous last words…LOL.)

As the pandemic effects began to wane and all of my friends and associates got inoculated, I began to wonder what it would be like to visit another house or apartment again. Amazing what we take for granted, isn’t it. Michael told me that his system was now totally different (remember, Michael is a reviewer so the gear comes and goes) and he invited me over to listen to the latest incarnation of his reference system.

Irony of ironies. I said yes, and a couple of weeks ago, with both of us fully vaxxed, made it back to the last place I visited prior to the world changing, across the Hudson from Manhattan, to Michael’s house once again.

This time, however, I was determined to really listen, eyes closed, to what many would consider a version of the ne-plus-ultra of high-end audio. This time, Michael was in the middle of listening to and reviewing three turntables. The models are irrelevant but what you do need to know is that these three tables exist on the edge of the analog art, fully loaded with at least one or two tonearms (depending on the turntable’s design) each. The list prices, minus power cords, interconnects and cartridges were roughly $250,000, $300,000 and $550,000.

A friend asked me what the difference is between a turntable that cost $250,000 and one costing $550,000. The answer? $300,000!

Seriously, I spent several hours at Michael’s this time. I sat down in the reference chair and listened, eyes closed, to some of the greatest analog playback gear that man has ever created.

Michael Fremer and the TechDAS

Air Force Zero turntable. Courtesy of Michael Fremer.

Some thoughts:

First off, the tables, using different arms and cartridges, made it impossible to discern why things sounded different. The only commonality then was the $5 piece of vinyl played.

Yes there were differences. Not better or worse. Just differences.

Michael is a very gracious host and answered my questions regarding the turntables’ differing technologies, but never chimed in as to what his opinions were. I assumed his reviews would speak for themselves and I respected that. I did point out to him what I thought I was hearing, however, and he was able to explain how certain design concepts made things sound the way they do. Two tables were direct drive, and the other one was belt-driven.

Car analogies always come to mind when I try to explain to my friends about the relative cost versus quality of super-high-end audio gear. (This is something I’ve had to revise after my visit with Michael.)

I always say that you can buy a Kia, then a Lexus, a Mercedes, a Rolls, a Maybach and ultimately a Bugatti. The prices of each rise enormously and one has to ask oneself, “why would I own any one of them?” The answer is, if you had the money and cared to know the differences, then the decision may be easier. You also may have all the money in the world but decide that you don’t need a Bugatti.

The problem with my car-versus-audio analogy is that, at least with cars, you can only make comparisons using each car’s unique technology – each car has to be taken as a whole. If you were to put the same tires on each car, for example, then the totality of the unique driving experience of each car would be seriously compromised.

On the other hand, in the case of audio systems, where each part is usually designed by a different manufacturer, a reviewer or listener can (using turntables as an example) choose from different arms, cartridges, and even record weights.

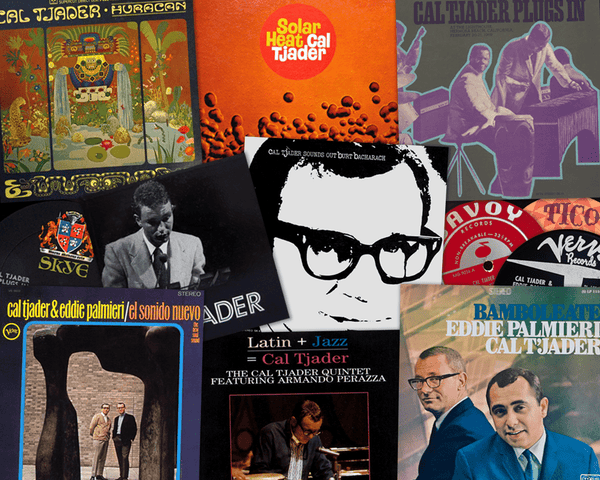

The reality of vinyl playback is that no matter how much money one spends on a turntable, arm, cartridge and phono stage, a major part of the sound you’re going to hear has to do with the quality of the vinyl – where and how it was pressed, whether it was one of the first or the last in the queue of the approximately 5,000 pressings the “mother” plate stamped, and so on.

You can’t retrieve what ain’t there to begin with, and that can happen with poor pressings.

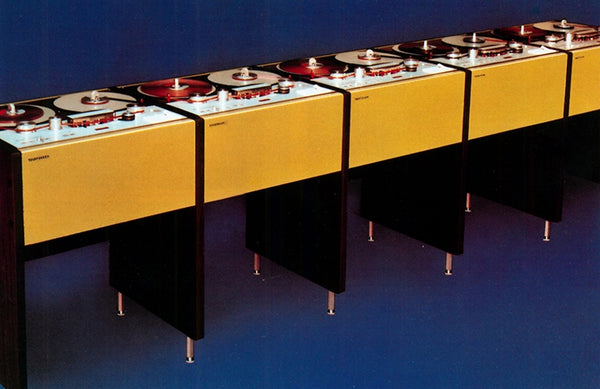

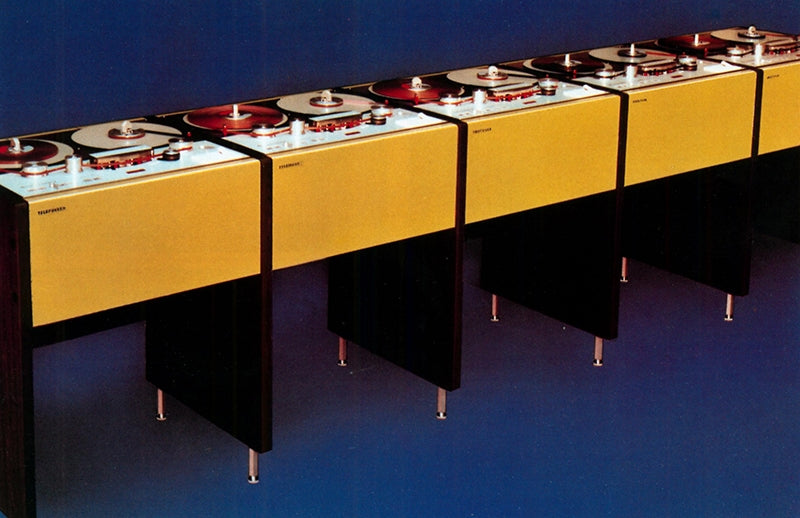

This is what Ken Kessler’s gripe about vinyl is all about, although he is a huge LP fan who owns great turntables. He knows that reel to reel tapes, for the most part, are copied from tape masters that are generations closer to the original master tapes than records are. I have been to Ken’s house and heard direct comparisons between commercially-sold reel to reel tapes, and their vinyl counterparts. The tapes kill the vinyl every time.

This however, is not about Michael’s system vs. Ken’s.

This is about the relative enjoyment one gets from a system regardless of price.

Listening to music on the gear Michael had was a revelation, for sure. Regardless of which turntable was used, the combination of his DarTZeel preamp, DarTZeel NHB-468 power amps and the Wilson Audio Chronosonic XVX loudspeaker was truly incredible. Instruments that I never knew were on the recording were in the mix in music that I thought I knew. Vocalists appeared in locations that were not there before. This is what money, technology and a proper setup can buy you. It had better do that! Otherwise, why bother?

My guess on the total list price of this system? Approximately 1.4 million dollars!

I left the house after several hours, contemplating where all this ultimately goes. About what this high-end journey is all about. About how far we have come and where we go from here.

And then…

My friend Ira has a friend Joe who has become a fan of streaming, and was selling his albums. Was I interested in possibly helping him evaluate his record collection for possible sale?

We went to his apartment on the Upper East Side. This was not any kind of hi-fi emporium. Just an apartment. In the living room was a small Cary SLI-80 tube integrated amp on the top shelf, a Parasound CD player below that. A Bluesound Node 2i streaming unit below that and an unconnected turntable on the bottom shelf.

Cary SLI-80HS (Heritage Series) integrated amplifier.

The speakers were a pair of older Audio Physic Scorpios.

According to Ira, who helped Joe put this system together, the list price of the amp, speakers, streamer, interconnects, speaker cable and power cords came to about $18,000.

After I went through the vinyl collection and cherry-picked some of the titles for myself, Joe asked me if I wanted to listen to his system. Not wanting to be rude, I said “sure.”

What happened next really blew me away.

His system, streaming CD-quality Qobuz only, sounded incredible.

Not only did it sound great but it “felt” right.

Yes, it just felt perfect. Like Michael’s but in a very different way

Was it the tube amp? The speakers? the room? It was all of it. Everything came together to make magic.

System and room matching, when done right, can make audio magic happen…regardless of price.

That made the trip to both locations all worthwhile.

Metallica WorldWired tour poster.

Metallica WorldWired tour poster.

Laconia Motorcycle Week, June 2021. From

Laconia Motorcycle Week, June 2021. From

Eat it if you dare! Durian, courtesy of

Eat it if you dare! Durian, courtesy of  Jellyfish with sesame oil and chili sauce. Courtesy of

Jellyfish with sesame oil and chili sauce. Courtesy of  Man making noodles in the restaurant Alón visited all those years ago.

Man making noodles in the restaurant Alón visited all those years ago.

Adrian Wu's completed Garrard 301 with solid cherry wood plinth, Tenuto gunmetal turntable mat, modified SME 3012 Series II tonearm and Ikeda 9TT cartridge.

Adrian Wu's completed Garrard 301 with solid cherry wood plinth, Tenuto gunmetal turntable mat, modified SME 3012 Series II tonearm and Ikeda 9TT cartridge.

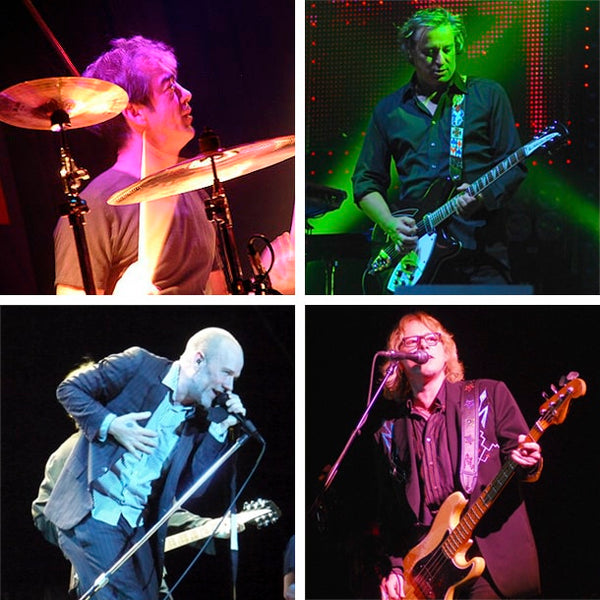

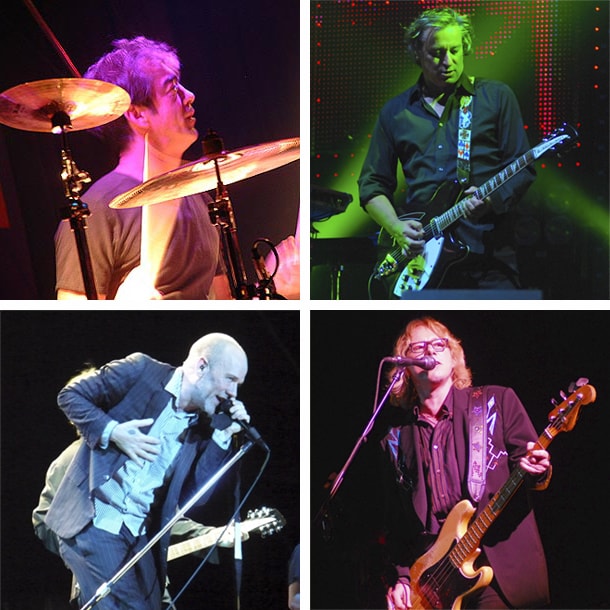

R.E.M., 2003. Courtesy of

R.E.M., 2003. Courtesy of

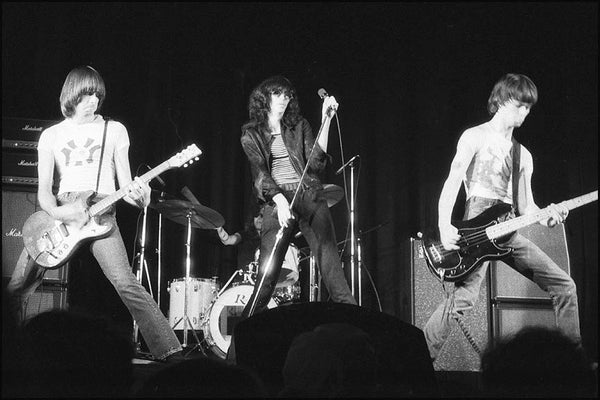

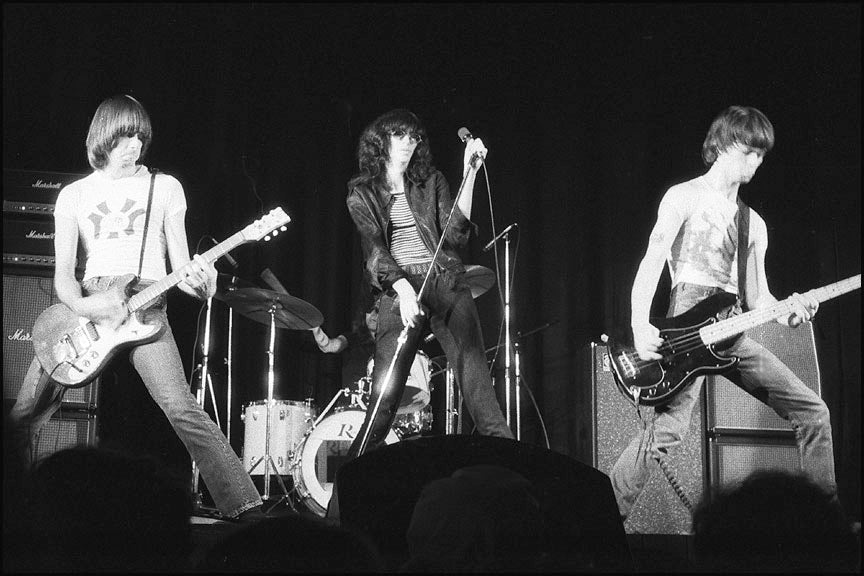

Ramones, the band's self-titled first album.

Ramones, the band's self-titled first album.

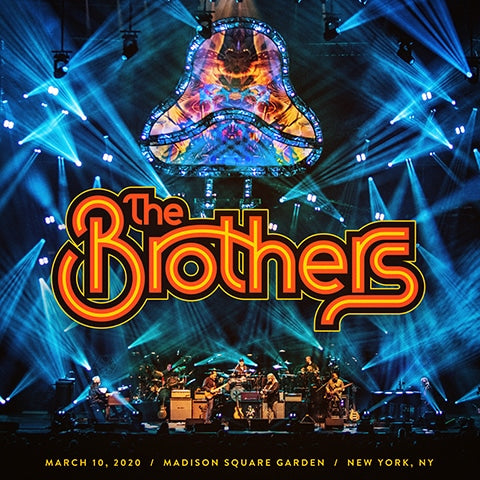

The Brothers: Duane Trucks, Derek Trucks, Chuck Leavell, Jaimoe, Marc Quinones, Oteil Burbridge, Warren Haynes, Reese Wynans. Photo courtesy of Kirk West.

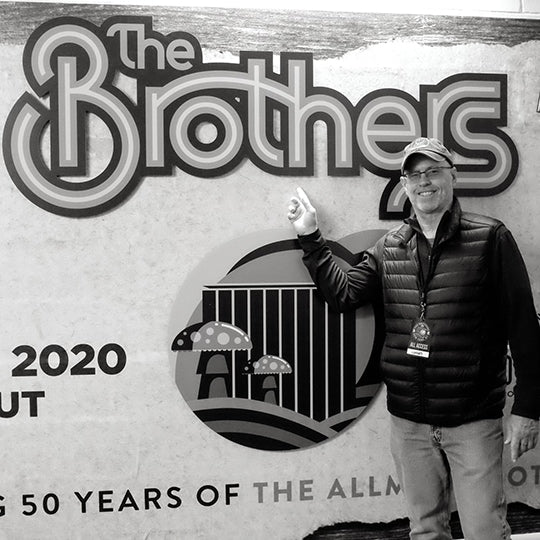

The Brothers: Duane Trucks, Derek Trucks, Chuck Leavell, Jaimoe, Marc Quinones, Oteil Burbridge, Warren Haynes, Reese Wynans. Photo courtesy of Kirk West. John Lynskey. Photo courtesy of Kirk West.

John Lynskey. Photo courtesy of Kirk West. Derek Trucks. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Derek Trucks. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Warren Haynes. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Warren Haynes. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Oteil Burbridge. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Oteil Burbridge. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Duane Trucks. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

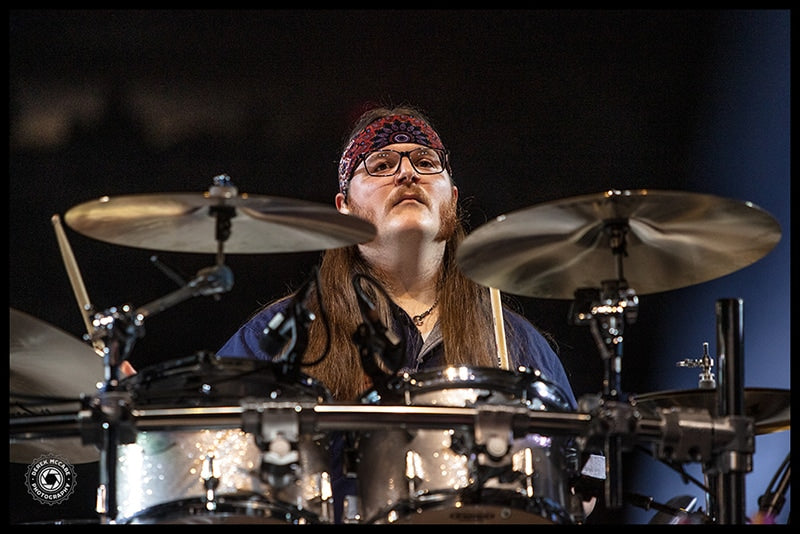

Duane Trucks. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Jaimoe (with Derek Trucks in shadow). Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Jaimoe (with Derek Trucks in shadow). Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Reese Wynans. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Reese Wynans. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Marc Quinones. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

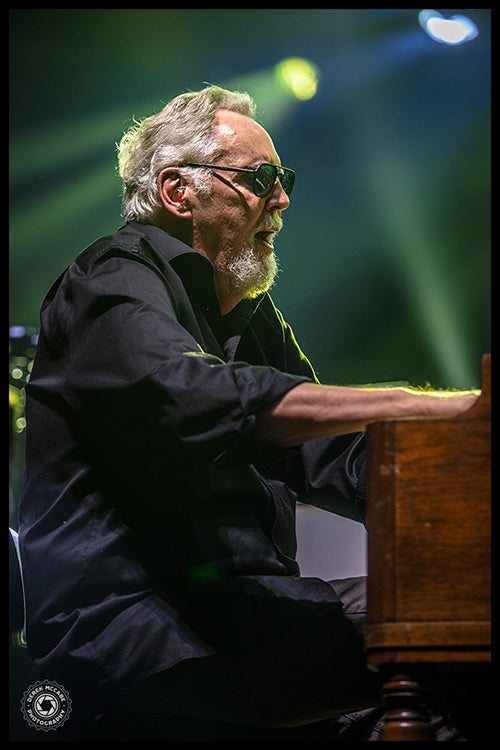

Marc Quinones. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Chuck Leavell. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Chuck Leavell. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe. Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes. Photo courtesy of Derek McCabe.

Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES:

Screenshot from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES: Screenshot photo from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot photo from Mapping voice gender and emotion to acoustic properties of natural speech, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Emotional and neurological responses to timbre in electric guitar and voice, courtesy of AES. Screenshot from Audio mythology, human bias, and how not to get fooled, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Audio mythology, human bias, and how not to get fooled, courtesy of AES.