Loading...

Issue 135

Moonlight Feels Right

Copper Listens to Copper: Stockfisch Records’ DMM Dubplate Vol. 1

Stockfisch Records is an audiophile label established in Germany in 1974 by owner/producer/engineer/Günter Pauler. The label has been releasing recordings on vinyl, DSD, SACD, Blu-ray and other formats and their artist roster includes Werner Lämmerhirt, David Qualley, Sara K., Allan Taylor, Carrie Newcomer, Katja Werker and a number of others. They also offer their TTC-Pro True Transmission Cable speaker cable.

I’d known of Stockfisch, but nothing could have prepared me for the record I recently received: Stockfisch’s DMM Dubplate Vol. 1. The disc is made from copper-plated steel and has a literally dazzling copper surface. It comes in a beautifully-presented box with a detailed booklet – and a pair of white gloves for handling the disc. The box is specially-designed to keep the record as pristine as possible, with a foam surround and a silicone top plate that holds the record securely in the box. I have never seen anything else like it. The record is slightly larger in diameter than a standard vinyl disc and has some weight to it.

Stockfisch DMM Dubplate Vol. 1.

The idea behind DMM Dubplate Vol. 1 was, like conventional direct metal mastering (DMM), to remove a number of the steps involved in physically mastering and pressing standard vinyl records (the need to produce a mother, father and stamper), and eliminate the generational loss resulting from the multi-step process. Stockfisch takes the idea further – the DMM Dubplate Vol. 1 is the master: it’s directly cut from the mastering lathe!

DMM Dubplate Vol. 1 includes five tracks from Chris Jones, Carl Cleves & Parissa Bouas, Ewen Carruthers and Sara K. Only one side has music, because the back side is not plated so music can’t be cut into it.

Before going any further, I know what you’re thinking, the same thing I did: will this metal record damage my stylus?

According to Stockfisch, no, and more on that later. I will admit being a little hesitant in dropping the needle of my not-inexpensive Grado cartridge onto the surface.

At first, I thought I had forgotten to turn my phono stage on. I heard nothing but quiet – no groove noise, no pre-echo, no nothing. But, no, my system was working; it was just that the surface of this copper-clad disc was remarkably quiet. I moved the tonearm further into the record…

I was astounded by what I heard.

I’ve been listening to records since I was a baby. I’ve heard hundreds, thousands, including a good portion of the audiophile classics – Casino Royale, The Sheffield Track Record, Mobile Fidelity Ultradiscs, you name it. Still, I was floored by the purity, dynamic impact, tonal richness and the stunning presence of the music. The impact is immediate – you just know you’re hearing something special; let the analytical brain kick in later.

There is an intimacy and, well, directness to the sound that really is remarkable – and will take any seasoned audiophile about five seconds to hear. For example, on the first cut, Chris Jones “No Sanctuary Here,” the bass has real weight and harmonic richness, not just “bass extension.” His vocal is upfront and palpable, in the midst of a deep soundspace. When the acoustic guitar takes a solo, there’s a point where you can hear the “ping” of the string plucked against the fret, one of many moments of startling realism here

On Carl Cleves & Parissa Bouas’ “Into the Light,” the presence of her vocal is so full and lush that I almost laughed out loud. Can a dobro sound lush? Yes, it can. Chris Jones’ “Fender Bender” is a dazzling, virtuosic duet between acoustic guitar and electric bass, with instrumental accompaniment, and here, you really feel the pace and drive of the music, and the guitar and bass remain totally distinct from each other even at breakneck speed. The fourth cut, Ewen Carruthers’ “When the Time Comes Around,” is simply gorgeous; I felt like I could walk into the sound.

I went into listening to Dubplate Vol. 1 with the preconceived notion that because of the reduction of the steps in the record-pressing process (and the elimination of generation loss), that what I’d hear is more of the “audiophile” stuff – more detail and low-level resolution. While there’s plenty of that, along with a remarkable absence of noise, what struck me the most is the increase in the palpability of the vocals and instruments, of the weight, of the tangibility of the sound. Everything sounds incredibly present, more real, more convincing.

The fact that this was cut from digital is going to make many LP purists take pause. I can tell you, it’s made me re-think the whole record manufacturing thing. How much of the record-pressing process is responsible for which sonic aspects? I thought I knew. Maybe not. How many times can you say that listening to something has been a learning experience?

Sure, the price of Dubplate Vol. 1 isn’t cheap, but then again, I’m sure the cost of manufacturing isn’t either. (Full disclosure: I don’t know anyone at Stockfisch. I requested a disc because I was intrigued by the technology. I didn’t know what it cost until writing the review.) I’m happy that Stockfisch even did this, a boundary-pushing attempt at achieving better sound, the kind of bold effort that makes the pursuit of high-end audio so thrilling at times.

I asked Stockfisch’s Günter Pauler to provide us with more detail on the disc.

Günter Pauler: We [have] cut 14-inch DMM masters that are sent to pressing plants for the production of vinyl records. We listen to these DMM cuts every now and again, comparing them with the vinyl LPs that have been pressed from the DMM master. We observed that the sound quality of the pressed vinyl always fell disappointingly behind the original DMM master.

Thus we came up with the idea for a 12-inch Dubplate, which we thought might be interesting for companies that develop and produce pickups for record players, because with the Dubplate they would be able to evaluate the true performance of their products by avoiding the pitfalls of pressed vinyl. Unfortunately no pickup producer was interested in this possibility. But the reaction we received from high-end listeners was just the opposite.

The 12-inch Dubplate is cut one at a time, just like its 14-inch counterpart [record master] that is sent to a pressing plant. The copper blank is made of a 1mm-thick stainless steel disc, which then receives a 0.1mm-thick galvanic plating of phosphate-copper. The 14-inch blank discs are not exactly flat, but rather a bit concave and uneven, because the melding of two different metals creates tension on the disc.

Inés Breuer, Hendrik Pauler, Hans-Jörg Maucksch and Günter Pauler of Stockfisch Records.

On 14-inch blanks this imperfection does not negatively affect the cut, because the disc is pulled flat under vacuum on the Neumann VMS DMM [cutting] lathe. Our 12-inch Dubplate, however, has to lie flat on the turntable of a record player, where only a maximum of 0.6 mm vertical movement is allowed. For this reason, our 12” steel blanks are made flat by means of a roller press which applies several tons of pressure. Not only is this procedure expensive, but we still discard about 30 percent of the blanks as not suitable. That’s why we sell the DMM Dubplate for a relatively high price of 700 Euros. We can only produce about five Dubplates each week, as that’s about the number of good blanks we receive per week.

The music on Vol. 1 comes from a digital master. On our Neumann VMS-82 we have a digital preview delay made by Daniel Weiss that is capable of 96 kHz. We could just as well use an analog tape as source, but it [would] have to be converted to digital in order to work with our machine.

Neumann VMS-82 cutting lathe.

We have played back the DMM Dubplate around 200 times, using test tones such as pink noise. There was no hearable loss in sound and no measurable wear on the stylus. On a regular pressed vinyl there’s a considerable loss of high frequencies after just 50 plays.

The equipment used to create DMM Dubplate Vol. 1 includes the following:

- Neumann VMS-82 cutting lathe

- Neumann SAL-74B cutting amplifier

- Weiss DLY101 cutting delay and D/A converter

- Weiss EQ1 mastering equalizer

- Waves Audio MaxxBCL signal processor

- Merging Technologies HAPI audio interface

- Benchmark AHB2 power amplifier

- Tannoy Prestige Canterbury Gold Reference loudspeakers

Cutting engineer Hendrik Pauler at work.

|

Stockfisch-Records Am Münster 30a 37154 Northeim Germany Tel.: +49(0)5551 61313 Fax: +49(0)5551 8020 e-mail: info@stockfisch-records.de |

|

Photos courtesy of Emre Meydan.

London “Decca” Cartridges: Unique Design, Timeless Quality

Decca cartridges are unique transducers with quite a bit of interesting history behind them, starring with the Decca company itself. From their 1929 beginnings as a British record company and gramophone (phonograph) manufacturer, the company later contributed to the 1940s war effort by developing radar and marine navigation systems. Decca produced records in both Europe and North America and quickly became the second-largest record label in the world, known for technical innovation and advanced recording techniques.

My vintage 1960 copy of the soundtrack album from Spartacus (the original, with Kirk Douglas) is a fine example of their work. The record is impeccable in every way, starting with the jacket and inner booklet. The vinyl record itself is quiet with outstanding dynamics that ebb and flow effortlessly, a lush, silken tonal quality, great soundstage depth, and fine detail with no etchiness in the sound whatsoever. (Decca Records is now part of the Universal Music Group.)

This is just a small bit of the colorful history of the Decca company, and if you find the subject interesting I suggest you read some of the many online articles about Decca. Even the origin of the Decca name may surprise you. It is the word “Mecca” with the initial “D” from their trademarked 1914 “Dulcetphone” replacing the M. It was also chosen because “Decca” was found to be easy to pronounce in most languages.

The Decca cartridge design is as interesting and unique as the company itself. It uses a “positive scanning system” generator design that is comprised of a piece of metal foil with the stylus mounted directly to it. This eliminates a conventional cantilever (and a sonic effect the company called “cantilever haze”) resulting in the shortest possible path from record to electrical signal. Along with the singular design and the sonic qualities of this cartridge, with its reputation for unrivaled musicality, also came a reputation for having many compromises, such as being unforgiving of dirty record and tracking abilities that fell well behind conventional moving magnet and moving coil designs.

Fast forward several decades and Decca is no longer in the business of manufacturing phono cartridges, the company having been sold in 1989. The cartridge design was licensed to Decca engineer John Wright, a license that is still in effect today. Now sold under the London brand name, “Decca” is often unofficially inserted into product description as the new manufacturer does not have the rights to use the Decca name. Referencing Decca makes the cartridge instantly recognizable to customers familiar with this unique transducer.

The latest London cartridges have been improved with a wider choice of styli and an improved mounting plate. All the cartridges, including the styli, are handmade in London to exacting standards, with the company being particularly proud of their stylus quality and the precise ways they are made and polished. The current London cartridge line-up is distributed by Pro Audio Ltd. of Tower Lakes, Illinois and is comprised of the following models:

Professional (DJ), $1,100

Maroon – Spherical, $950

Maroon DP*, $1,100

Gold – Elliptical, $1,200

Gold DP, $1,400

Super Gold – Line Contact Super, $1,500

Gold DP, $1,600

Jubilee – Line Contact, $3,000

Reference Low-Mass Fine Line, $5,000

*DP = Decapod

Any of the cartridges are available in mono or 78 RPM versions by special order. Re-tipping and servicing is available for all models as well.

As part of this feature I was loaned a London Super Gold cartridge to review and provide an update on a modern version of this classical, historically relevant piece of audio gear. I was most interested in seeing if the mythical status of the Decca cartridge was deserved, in both its positive and negative aspects. I used it with my Technics SL-1200GR feeding a Graham Slee Accession phono preamp. The Super Gold has a strong 5 mV output so no special phono preamp is required, and it tracks at 1.8 grams. The cartridge starts sounding its best after 30 hours of break-in so if you try the cartridge be sure to give it enough time to open up.

The legendary musicality is definitely not a myth. Whether it is the elimination of “cantilever haze,” the unique transducer itself or a combination of the two, there is something special to the sound that is different from other cartridges, analogous to the way that planar speakers are different from speakers with dynamic drivers. It made some of my $800 moving magnet and moving coil cartridges sound almost digital at times, and not good digital at that. Though the difference in price would certainly justify it in sounding so much better, as I mentioned before, there is a difference to the sound that is difficult to quantify.

There is an immediacy and clarity to the music that has to be experienced to be appreciated, along with tonal color and roundness I have never heard from any other musical component or transducer of any kind. Listening to the soundtrack from Breakfast at Tiffany’s featuring the music of Henry Mancini, the percussion had an immediacy and clarity I have never heard on that recording. The strumming at the beginning of “Moon River” had a richness and silken tonality that made took the listening experience to a new level.

The notion that the cartridge is intolerant of less-than-perfect vinyl also has some basis in reality. The qualities that make it so good at extracting music out of the groove make it somewhat unforgiving if your records are not well cared for. It is not unlistenable in these cases, but it seems to make imperfections come to the forefront a bit more than other fine cartridges I have used. If anything, the Decca Super Gold will encourage you to keep up your vinyl as pristine as possible. There is not much clearance between the stylus and the cartridge body so I recommend checking it frequently for dust build-up. The very fine stylus of the Super Gold managed to collect dust from records that were quiet and seemed clean, and if you have any accumulation it will degrade the sound more quickly than with other cartridges. Keep that stylus brush handy!

Tracking was not an issue whatsoever and the 1.8-gram tracking force handled everything I threw at it. I did find the set-up to be somewhat fussy, and if you have an arm with easily-adjustable VTA it will help you get the most out of the cartridge.

If you are looking for something to take your analog system to the next level and are willing to try something different, London Decca cartridges definitely belong on your shopping list. You will not only experience the distinctive and beautiful sound, you will also enjoy the pride that comes with owning something classic, unique and a part of audio history.

Manufacturer’s website:

http://londondeccaaudio.com/

US Distributor:

Pro Audio, Ltd.

111 N. South Dr.

Tower Lakes, IL 60010-1324

847-526-1660

Photos courtesy of Don Lindich.

Heart’s Ann Wilson: Wandering Through the Wonder

For a musical genre known to favor male vocalists, there are few men or women who have made the kind of impact that Ann Wilson has on rock n roll. As co-founder of the band Heart, she and her sister Nancy joined forces to deliver a sound that would shake the understanding of what we all thought was possible within the realm of rock. Together they wrote songs that were slightly dark, wet and raw, much like the climate of their native Seattle. Like the greats from that town who preceded them, they forged a path that quickly became impossible to ignore.

For those of us who grew up with their music, beginning with their 1975 debut, Dreamboat Annie, it wouldn’t be until later when we heard about the complicated relationships that existed within the band, and that likely informed their creative process. It didn’t matter. When a Heart classic emerged on a roadhouse jukebox we all found our way to our feet and we celebrated a rock and roll union that was honestly like no other. Heart was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013.

The Wilson sisters have evolved their sound across genres and have kept their focus on bringing great energy to everything they do. Recently, Ann Wilson has been delivering new singles that tie back to Heart’s earliest recordings. They exhibit a raw, fuel-injected approach that perfectly syncs with her vocals in ways that will keep you wondering how she never seems to lose a step. It’s a prolific period for Ann, who just spent time at Muscle Shoals’ FAME Studios cutting new tracks and who is about to release a quartet of her earliest bands’ first recordings.

Ann Wilson is someone who never stopped believing that rock n roll could save your soul. In our recent exchange she proved that and more.

Ray Chelstowski: Gene Simmons and others have said that rock is dead. What do you think is the future for rock and roll?

Ann Wilson: I think that it’s incredibly short-sighted to say that rock is dead. I mean, that doesn’t pay any homage to history because many times over the decades (like in the disco era) people have said this, but rock has always kept on simmering underground, which is where it was born because it’s a revolutionary art form. The more flack that it gets the better it gets. I see the future of rock as being really bright. There are all of these performing bands that have been off the road for a year and a half and if you don’t think that they aren’t coiled up and ready to strike you’re crazy. There’s a lot of pent-up energy out there right now. So I think that rock is probably gonna come out swinging.

I also think it’s a mistake to mix up the world of rock performance and music with the Grammys and industry metrics like how many records you sell. I don’t think [it’s] right to equate commercial success with the life of the genre because the real thing about rock is its spirit and it’s “f*ck you-ness.” That’s not going to go away.

RC: Your latest singles: “Tender Heart,” “The Hammer,” and your Steve Earle cover, “The Revolution Starts Now” cover a lot of ground. What is the strategy behind what you are recording and releasing these days?

AW: They all represent things that are inside of me. I grew up as part of the Beatles generation where an album was more like a variety show. You just didn’t do one thing; you went to all kinds of places. That’s what’s happening with these songs. I just recorded four more down in Muscle Shoals that are like that too. I’m doing some more in about a month that are yet again different, so I’m exploring all corners of my creative self.

RC: What’s it like recording at Muscle Shoals where so many other big voices like Aretha Franklin, Etta James, and Wilson Pickett cut some of their best-known hits?

AW: Well Muscle Shoals has a soul of its own. I think I felt empathy for Aretha and Etta because they were young and shy when they were there but they delivered. That’s how I felt when I was there. I felt shy because I was in there with some players who were just beyond the beyond – real heavy hitters. I had to rise to the occasion and the studio was a really welcoming place to do that. It was also pretty cool to take a break and walk into the ladies restroom and see a picture of Aretha (laughs).

If you look at it scientifically, it just might be that the magic of Muscle Shoals comes from how the people who go in there believe that it’s magical so it is! The power of that belief can create reality.

RC: It took a while for you to release your solo debut, Hope and Glory in 2007, and then its follow-up, Immortal in 2018. Both were really well-received so why so much time between records?

AW: The first solo record came about because Nancy was married to Cameron Crowe at that point and she was scoring his movies. So, Heart was dormant and I was climbing the walls. So I made a solo album and it was really great. It helped me level up. Then when I got back together with Heart I was that much more ahead in terms of my self-confidence in what I could do. The same thing happened with Immortal, my second solo record. Then the stuff I did with the Ann Wilson Band (The Ann Wilson Thing!) had me doing my solo stuff alongside Heart material, which was just really nourishing for me as a singer. It was just great.

RC: You are also about to share some music you recorded in 1969 with your original band, Ann Wilson & The Daybreaks. What will fans discover in these songs?

AW: They have been a kind of whimsical funny thing from the early days, way before Heart, that my manager felt were valuable for the present. So we had them remastered so that they would sound their very best. It’s four songs (two singles sides). Three of them were country songs by local Seattle country songwriters who just needed a band to come and record their songs so that they could try to shop them around. There was one side left over and they let me fill it any way that I wanted. It just so happened that Nancy and I at that time had written our first song together called “Through Eyes and Glass.” So we actually recorded that one. It was when I was at art college so I was probably eighteen and I was going to school by day and singing in a band at night.

RC: How do you think the music will be received?

AW: To my ears now is sounds super old-timey. It’s got this reverb all over it and it’s totally country. The guys that were playing in my band were stock musicians; just old workhorse guys, so there’s a real everyman quality to their sound. And of course I sound like I’m about twelve (laughs). I had no studio experience before that so I sound kind of scared. Kind of reckless and naive!

RC: I re-watched Heart – Behind The Music, and maybe for the first time really saw the symmetry that exists between your 1970s sound and what emerged from Seattle in the early 1990’s. What is it about that town that informs the creative process?

AW: Well the thing about Seattle is that for nine months out of the year it’s overcast, dreary, drizzly, and cold – that kind of worms its way into everyone’s mood. People are introspective, and while they may try real hard to be chipper and ironic they don’t ever completely make it. So that’s where I think the earlier music like Jimi Hendrix and Ray Charles, to Heart, and then later on to the bands of the ’90s, creates a stream that reflects what the atmosphere and climate are like. It’s what people’s emotional landscapes in Seattle tend to be like.

RC: Your music in the 1980s didn’t have that kind of coloring.

AW: That’s when we left town to work in other studios and places. We had been listening to record companies who said, “Oh no, don’t do your songs. That’s not what’s being played on the radio. Do this instead.“ We made a Faustian bargain and had super commercial success. But it really wasn’t us. It was like putting on a suit of clothes that really didn’t fit. It was super sexy so people bought it, but we didn’t. It was uncomfortable. So we went back to Seattle and decided to do The Lovemongers. We’ll dry out here and rediscover ourselves. So yeah, Seattle is a spiritual home.

RC: I’m always amazed at how much musical ground the band Heart has covered. Is that a reflection of the kind of musical household that you grew up in, listening to everything from classical to Judy Garland?

AW: Oh yeah. The radio was always on and there was always an album playing – somebody’s music was always on. So it’s no big deal to just thumb through my encyclopedic memory of songs throughout my life and just bring them out.

RC: Your new material finds you in great voice. What is your secret to keeping your vocals in such remarkable shape?

AW: I don’t think there’s any secret. Your voice is just a tunnel that your soul passes through when you sing. If you practice just normal horse sense as you would with any other part of your body, your throat’s going to agree with whatever you want to put through it. But I do a couple of things like taking massive doses of Arnica when I’m on the road. That helps with the swelling and bruising that comes from singing rock for two hours straight – which is kind of like being in a football game.

RC: Jimmy Page famously toured with the Black Crowes, revisiting Led Zeppelin’s music. Have you ever thought about fronting a “guy band” and heading out on tour together?

AW: Yes I have. I would love to front Soundgarden! I would love to also front a band with Jimmy (Page) and John Paul (Jones) and somebody playing drums. If the band was digging what I do and open minded I’d totally do it.

RC: Have you ever considered taking one of your classic albums on the road and building a tour around it like Bruce Springsteen did with The River?

AW: Yeah; one year we did Dreamboat Annie. We didn’t do it on a tour though. I think that would be really fun. We are hard-pressed though to find an album that I think is brilliant all of the way through, where every song is just great! You know, like what Lucinda Williams could do with Car Wheels on a Gravel Road because that album is just a masterpiece. If you’re going to do a concert and expect people to sit there and just dig it, then every song has to be up to a certain standard. But probably something like Little Queen could do that.

RC: After the new material is all released, what’s next? Is there anyone you are looking to collaborate with?

AW: In June I have four shows scheduled in Florida with my new band. After that hopefully we’ll be able to go back on the road and actually tour. No one can say how that’s going to actually happen but it will because there are too many people who want it.

In terms of collaborations I think that you do one thing and it opens up other doors. It’s more like wandering through all of this wonder and figuring out where to go next.

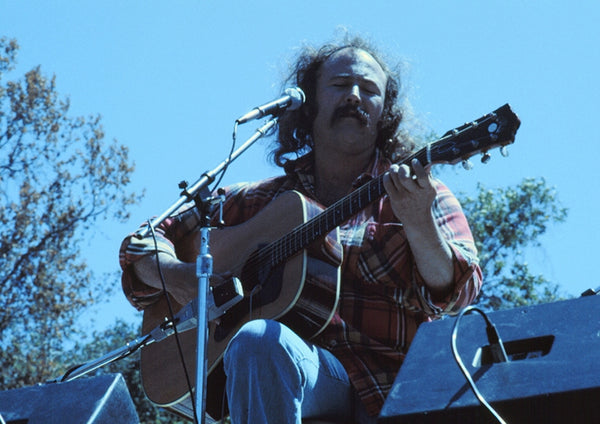

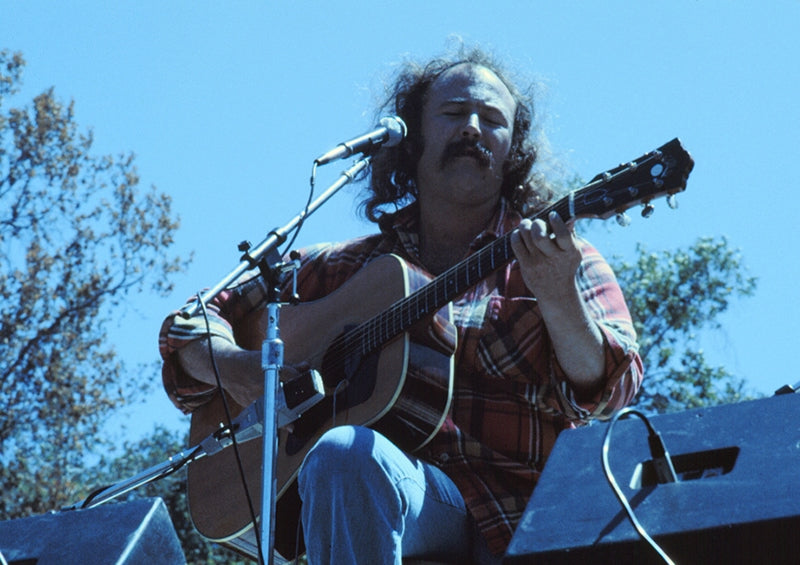

Paul Brett: Guitarist, Designer and Collector of Rare Instruments

Paul Brett is a renowned guitarist, performer and recording artist. He’s also an instrument historian and designer, a journalist, and a collector. Paul has played with the Strawbs, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Roy Harper, the “King of Skiffle” Lonnie Donegan and others, and here he shares some of his musical highlights spanning the decades.

Russ Welton: What is your favorite instrument from your collection?

Paul Brett: Funnily enough, it’s not a guitar! A couple of years ago I acquired an excessively rare Irish traveling harp made by the legendary John Egan. I can’t play harp but as a collector, I couldn’t resist getting it as there are very few about and none I can find outside of museums. There is something magical about it and it looks great. It was sold as part of a household clearance and the seller was after antique furniture. They did not know who the harp actually was made by, so I picked up a bargain!

Guitar-wise, I have a couple of early 1800s harp guitars by English luthier Edward Light. These were the forerunner of the harp guitar as we know it today. Its big brother emerged in the early 1900s. My 1916 Gibson Style U harp guitar is a museum-quality example and recently won first prize in the Britain’s Rare Guitars Show.

Apart from these, my favorite actual guitars in my collection are a Lead Belly-size 1930s Oscar Schmidt Stella 12-string, and a 1938 Stella Westbrook 12-string played by the legendary Blind Willie McTell. I am also in love with my self-designed Vintage Viator 12-string. I have just completed an original 15-track album using it with a string quartet.

RW: Which acoustic instruments have you found to be significant milestones in the development of the guitar itself, and in your own playing?

PB: To define the beginning of the guitar is impossible. 3,500 years ago, a tomb was discovered in Egypt containing the mummified corpse of a musician named Har Mose. He was clutching a three-stringed tanbur with a wooden pick attached. It looked like a paddle or cricket bat but was obviously playable. It is currently residing in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo. So, if we take this as a start, a three stringed instrument with a pick, then we can progress the development from there. We can thank the Moors for bringing the oud into southern Spain, from which all hell broke loose regarding its morphing into the guitar and its various guises throughout the ages. It would take a very large book to list all the manifestations and styles of the guitar’s rise through the centuries and we haven’t got the space here to cover it.

Throughout my career as a guitarist, I have never limited myself to one style or genre of playing. I always learned the many different aspects of what that piece of wood and metal was capable of, and I still do today.

RW: Who would you say have been the most popular voices in the development of pop music during your career, and how so?

PB: If your question refers to modern popular music, then you would have to mention Bill Haley, Elvis Presley and other greats from that 1950s birthing era. I would include someone who I had the pleasure of playing lead guitar with, Lonnie Donegan. Without Lon’s input in the UK, certainly British popular music would not have taken the path it did (he was Britain’s biggest artist before the Beatles), I was influenced by many players and artists. In the early days, Duane Eddy, The Shadows, Charlie Byrd, Segovia, Wes Montgomery, even jazz sax players like Ben Webster.

I would have to say the standout artists who have influenced my career, especially in the formation of Paul Brett’s Sage, have to be Ritchie Havens and to a lesser extent, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, insofar as the use of vocal harmonies were concerned.

RW: What inspired your own development of your own line of guitars through guitar company Vintage?

PB: When I was playing with 12-string blues legend Johnny Joyce in the ’60s and ’70s in various line ups, I caught the bug from him regarding the makes and models of guitars the blues legends played. These were not top-of-the-range name brands, but many fell under one brand, Stella. These were made in New York City by a German immigrant, Oscar Schmidt, who set up a factory there. From 1939, they were made by Harmony. They were considered “workingman’s guitars” as they were cheap. Many were made of birch and ladder-braced in construction. (This is an earlier way of reinforcing the top of a guitar, as opposed to the “X” bracing and other types used today.) Back in the 60’s in the UK, it was almost impossible to find one of these Stellas.

We only heard these early Stellas on crude recordings of American blues pioneers like Leadbelly, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Son House and others. So, we trawled the junk shops and found some, which Johnny repaired, and we were caught in their spell, as they produced what is now referred to as “That Sound,” especially for blues. From that time till now, I have made it my mission to collect, record and film as many of these early iconic guitars as I can. This was the main influence of my guitar designs for Vintage.

RW: How do you decide on which instruments to develop for Vintage?

PB: I look at gaps in the market. I use my collection of old guitars as references, and come up with design ideas and present them to operations director Paul Smith at Vintage, who then seeks the go-ahead to put them into production from managing director Dennis Drumm. If approved, we send the designs to be made.

At Vintage, we are always conscious of keeping the quality up and prices down. Hence, we have adopted the old principle of workingman’s (and woman’s) guitars that are affordable and offer great value for money.

RW: You have 20 Paul Brett Signature models in the Vintage range. How would you advise new players on choosing which ones to play?

PB: Just look at the range of acoustics and acoustic-electrics. See which one might fit the bill for what you are looking to achieve and if possible, try one out. I have uploaded lots of videos to YouTube of all my Vintage range, plus loads of early Stellas and many other brands that were popular in earlier times. So, you can see and hear them being played and not just see ads and photos of them.

RW: Which instruments does Phil Beer of Show of Hands play?

PB: Phil is one of our best all-round players. He endorses and plays the Viator travel guitars, both the 6- and 12-string models. He has posted videos of him playing these models in a different style to what I play, showing the versatility of these little powerhouses. Gordon Giltrap, Steve Tilston, Carrie Martin and others also play Viators.

RW: Toby Lobb of the UK shanty group Fisherman’s Friends plays your guitars. Tell us about that.

PB: Toby uses my instruments on the group’s records and videos, and his solo CDs. I am happy he has chosen to play my guitars and it spreads them to another genre. They are the leading group in that genre in the UK and one of my favorite live bands. One of the most enjoyable concerts I have been to prior to lockdown. No hype, just good old sea shanties delivered by genuine people who know how to present their art in live performance.

RW: You have a new album coming out and it’s a compilation on Cherry Red Records, who have released artists and records like the debut Genesis album (From Genesis to Revelation), Toyah, Sir Lord Baltimore, Hawkwind and others. Tell us about your album.

PB: I was approached by John Reed of Cherry Red Records to sign up my catalogue. Once we had made the deal, John suggested putting out a 4-CD anthology that represents a selection of my recorded works from the 1960s until now. It was released on March 29.

I am very pleased as I did not realize I had done so much over the years. It’s only when I sat and listened to 94 tracks across 50-plus years of recording that I took in the variety of styles and genres and the bands and musicians I had played with over the years. Here is the link if anyone wants to get a copy:

RW: You will soon be making an appearance on Netflix. Tell us about your involvement.

PB: Dennis Drumm of Vintage was approached by an American production company to make a film about vintage guitars for Netflix. The producer requested that I take part and show some of my instruments. This will be happening imminently.

RW: What future projects can you tell us about?

PB: I am currently liaising with a TV production company to make a six-part TV series based on the “History of Guitar” series of articles I wrote for Acoustic magazine. Vintage and I are also in the process of designing a tribute 12-string in memory of Johnny Joyce.

For more information about Paul please visit:

Down the Rabbit Hole of SACD Ripping and DSD Extraction

I’m a firm believer in fair use when it comes to audio media — if you bought it, you own it, and you’re free to do with it as you please — as long as it’s for your personal enjoyment and you’re not trying to sell it illegally for profit. Apparently the code writers/hackers in the world agree with me, and it’s really great that we can finally transcode just about any digital file type that exists to ensure compatibility with ever-evolving audio equipment. I’m departing from my usual review format to focus on a developing technology I’ve been following for several years now, which is the ripping of SACD discs and the extraction of the Direct Stream Digital (DSD) layer. I first became aware of this about three years ago, and have followed its progress with great interest, although I haven’t had the tools available to me to make this happen until just a few weeks ago. Why a nearly-dead, niche technology like SACD, you may ask — my involvement with it goes all the way back to my very first gig in audio journalism, twenty years ago at the old Audiophile Audition website.

I wrote my first piece for Audiophile Audition in 2001; the SACD format had been unceremoniously launched the year before to very little fanfare. SACD offered great promise, with many technological positives; the only real downside being the somewhat prohibitive cost of the discs and players. In the year following SACD’s release, John Sunier (the now-deceased editor at AA), offered me what would prove to be a ridiculously generous and nearly unlimited flow of SACD discs from all the major record labels. I also received discs from a multitude of smaller labels who were eager to jump on board the SACD bandwagon — and I didn’t even have an SACD player at the time. Fortunately, manufacturers and record company reps were keen to get information about the new technology out there, and were very accommodating when it came to getting hardware into the hands of reviewers.

My experience with SACD was that its playback was revelatory; no other digital disc could come close to providing the level of clarity, organic purity, and very nearly analog-like sound quality. By the time the major labels pulled the plug on the format in 2009, I had amassed a collection of over 300 titles. And I’ve added more in the decade since then, bringing me to a total of about 400 discs. I don’t play them as much as I’d like, because I’ve pretty much become a slave to the convenience of streaming digital music. I’ve purchased a number of high-res downloads — including some DSD downloads (about a dozen). However, the cost is prohibitive, so I haven’t gone all-in with DSD downloads. But having so many SACD discs on hand, I’ve always dreamed about being able to add those to my digital music library for convenient playback.

The first time I read anything online about being able to rip an SACD, it involved what appeared to be a mega-complicated process of exacting procedures, requiring very specific, no-longer-in-production equipment with very limited availability. At that point, this was limited to certain Oppo universal players and early Sony PlayStation models. And if the firmware on any of those units had been updated beyond a certain point, they would no longer perform the process, which was fairly long and involved, and apparently placed a significant strain on the lasers of the units being used for ripping. You’d read lots of threads with people literally pulling their hair out over failed ripping attempts, or over finally locating a correct Oppo or PlayStation unit, only to find that they’d been run to death ripping SACDs. Becoming an SACD-ripping early-adopter didn’t appear to be in the cards for me.

I pretty much had given up on it until about a year ago, when I stumbled onto a thread linked to the Sonore (manufacturer of Rendu streamers and associated equipment) website that referenced a program called ISO2DSD. Googling that eventually led me to the HiFi Haven website, where there’s an entire thread dedicated to ripping SACDs. Which is a tad daunting, because the thread has 140 pages of comments that range from relatively cryptic tidbits of absolutely essential information, to full blown rants detailing chaotic failures at the process. I waded through a mountain of detailed information for seemingly countless hours — even days — and eventually picked up some essential clues on how to make the process actually work. I’d recommend going ahead and registering for the site — like I did, you may find yourself occasionally stuck in the process, and have a need to reach out to anyone who might be able to provide some guidance or perhaps a clarification.

The process of ripping SACDs has gotten significantly easier over the last couple of years. I guess there are folks out there with lots of time on their hands, the ability to write sophisticated programs that have seriously simplified the process, and the time to test a ridiculous variety of players to confirm whether they will actually work with the programs. The very first step can be found on the HiFi Haven website, on page 1 of the thread, midway down the page, where there’s a comprehensive listing of player models that will work for SACD ripping. These are all currently Blu-ray players (that support SACD playback) that incorporate a MediaTek chipset that’s needed to make ripping possible. The MediaTek chipset was introduced in 2010, and was commonly used in the players listed below from 2012 through 2017. That list currently includes:

Sony brand compatible Blu-ray players:

BDP-S390 (also sold as BX39 in some markets)

BDP-S490

BDP-S590 (also sold as BX59 in some markets)

BDV-E190

BDP-S4100

BDP-S5100 (also sold as BX510 in some markets)

BDP-S6200* (also sold as BX620 in some markets, requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript sacd_extract_6200 version)

BDP-S7200* (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript sacd_extract_6200 version)

BDP-S790* (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version/S790 variant)

BDP-A6000* (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript sacd_extract_6200 version)

BDV-NF720 (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript sacd_extract_6200 version)

BDP-S6500* (also sold as BX650 in some markets, requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version/S6700 variant developed June 2020)

BDP-S6700 (not recommended, only certain early production is compatible)

UHP-H1 (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version/S6700 variant developed Jun. 2020)

Pioneer brand compatible Blu-ray players:

BDP-80FD

BDP-160

BDP-170

MCS-FS232 * (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version S6200/7200 variant)

Oppo brand compatible Blu-ray players:

BDP-103 and 103D

BDP-105 and 105D

Cambridge brand compatible Blu-ray players:

Azur 752BD

CXU

Arcam brand compatible Blu-ray & CD/SACD players:

FMJ UDP411

FMJ CDS27

Primare brand compatible Blu-ray player:

BD32 MkII

Electrocompaniet brand compatible Blu-ray player:

EMP3

Denon brand compatible Blu-ray player:

DBT-3313UD and 3313UDCI* (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version/S790 variant)

MSB Technology brand compatible Blu-ray players:

Universal Media Transport V

Signature UMT V

Yamaha brand compatible Blu-ray Player:

BD-S677

Marantz brand compatible Blu-ray player:

UD7007* (requires Sony ARMv7 AutoScript version/S790 variant)

I’m pretty certain few (if any) of the player models listed are in current production, and some of the Sony models sold for less than $100 USD when brand new at stores like Target, Costco, and WalMart. A number of them can be found online at sites like eBay for around $50 or less, and numerous posters have detailed finding one of the player models at thrift stores like Goodwill. I bookmarked the model listing page on my cell phone and started a casual search for one of the players; I often frequent thrift stores looking for cheap CDs, and virtually every one I go into regularly has a half-dozen or so Blu-ray players priced anywhere from $10 to $20. From all accounts on the HiFi Haven SACD ripping thread, one of the players that’s most commonly available and used for ripping is the Sony BDP-S5100 (also sold as BX510 in some markets). I decided to forego the online search for one of the players, choosing instead to trust dumb luck in finding a functioning unit in a thrift store.

My frequent thrift store searches were unsuccessful over a period of about a year, until a couple of weeks ago, when I found a very clean Sony BX510 player at a Goodwill for $11. Woo hoo! I have a personal theory that a lot of disc players donated to Goodwills and the like were probably only used for DVD or Blu-ray playback, and probably not subjected to extreme usage or abuse, meaning that the SACD drive function is more than likely pretty pristine. The BX510 I scored came without a remote; being able to access the player’s setup menu is essential to getting the ripping process to properly function. Luckily, I happened to have a newer model Sony Blu-ray player (purchased at WalMart for about $50) in my living room, and its remote worked perfectly with the BX510. Barring all else, working remotes can be gotten from Amazon for less than $10.

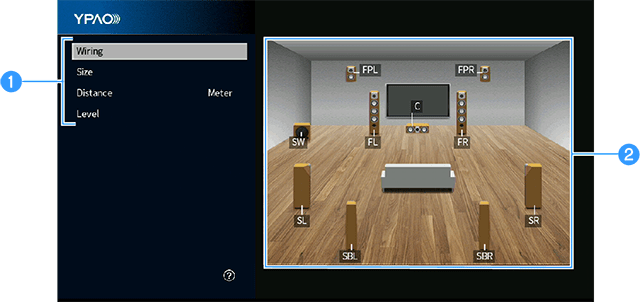

You’ll need to connect the player to a monitor or TV, and you’ll need the remote to make a few basic settings on the player’s on-screen setup menu. 1) Go to the Audio Settings tab, and turn the DSD Output Mode to “Off.” 2) Then go to the BD/DVD Viewing Settings tab and set the BD Internet Connection to “Do Not Allow.” 3) Go to the Music Settings tab and set the Super Audio CD Playback Layer to “SACD.” 4) Go to the System Settings tab and set the Quick Start Mode to “On.” I also set the System Software Auto Update to “Off,” even though the current conventional logic is that it’s no longer critical to the machine’s ability to rip SACDs. 5) Finally, you’ll need to go to the Network Settings tab and choose between “Wired” or “Wireless” — once again, the original thought process with SACD ripping was that wireless wasn’t feasible because of the huge data transfer going on, but recent experiences have shown that not to be the case. I’ve actually had good success with a wireless connection, so whichever path you choose should work for you.

Okay, so now that you have your player set up, there are a couple of other considerations that need to be made. First of all, you need to download the latest version of JavaOS for your computer’s OS; the ripping program is based on Java, and requires a minimum of Java Version 8 to function properly. Most computers use Java to assist or manage a variety of functions, but you do need to confirm that you at least have Java Version 8 running.

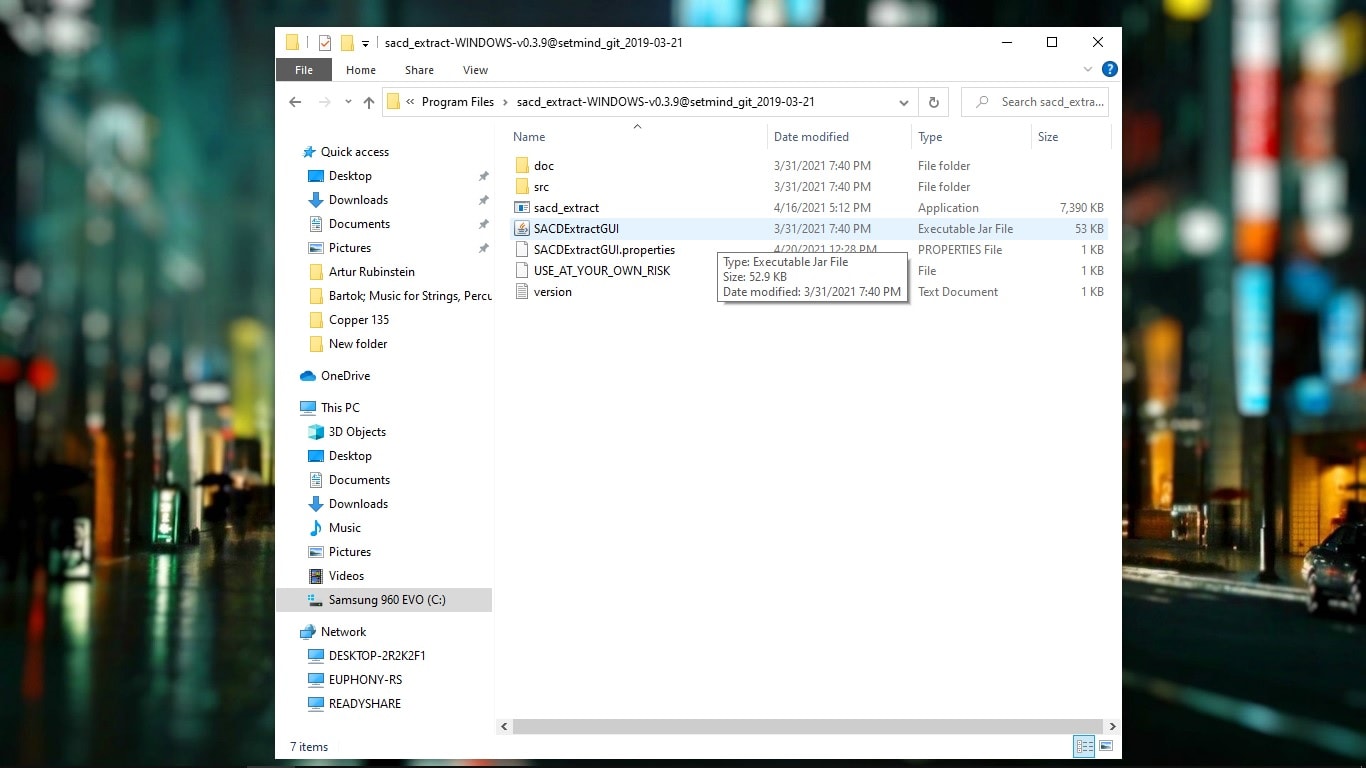

The biggest advance in SACD ripping came with the introduction of the SACD Extract GUI software in 2018. The software will work in Windows, Mac, or Linux environments; when you click on the link, it takes you to page 15 on the HiFi Haven SACD ripping page. In the post, you’ll see two buttons marked “Spoiler: AMD/Intel” and “Spoiler: Raspberry PI”; click on the one that pertains to your computer system processor setup, and opening them will reveal the download links that match your OS. Download the .zip file, extract it, and place it not buried too deeply on your system hard drive; for example, if using a Mac, place it in the Application folder. With Windows, place the file somewhere on your “C” drive, like in the Program Files folder.

The biggest advance in SACD ripping came with the introduction of the SACD Extract GUI software in 2018. The software will work in Windows, Mac, or Linux environments; when you click on the link, it takes you to page 15 on the HiFi Haven SACD ripping page. In the post, you’ll see two buttons marked “Spoiler: AMD/Intel” and “Spoiler: Raspberry PI”; click on the one that pertains to your computer system processor setup, and opening them will reveal the download links that match your OS. Download the .zip file, extract it, and place it not buried too deeply on your system hard drive; for example, if using a Mac, place it in the Application folder. With Windows, place the file somewhere on your “C” drive, like in the Program Files folder.

The download package includes a number of files, but only two require any attention from you; the one named “SACDExtractGUI” is the actual application and visual interface that you launch every time you rip an SACD. The second file you need to be concerned with is one that’s named “SACD_Extract”; this is an executable program that governs the ripping process on your computer. No installation is necessary of any of the executable (.exe) files; they automatically run when the program is launched. All the software here is open source, which means that many developers are making regular improvements; one just happened recently that has fixed some problem issues I had with certain discs not ripping. This tends to be a problem most often with classical SACDs, where the metadata character string for a particular file exceeds 256 characters — it happens a lot more often than you might imagine, and the ripping software originally couldn’t process files that exceeded that limitation. Fortunately, there’s a fix; go to page 142 of the HiFi Haven thread; midway down, click on the link EuFlo’s GitHub repository, and scroll down to the bottom of the page. Choose the -99 link that matches your operating system. Extract the files, then delete the “SACD_Extract” file from your existing software folder and replace it with the new one you just downloaded. So far, everything I’ve ripped has worked perfectly with the new executable file.

The download package includes a number of files, but only two require any attention from you; the one named “SACDExtractGUI” is the actual application and visual interface that you launch every time you rip an SACD. The second file you need to be concerned with is one that’s named “SACD_Extract”; this is an executable program that governs the ripping process on your computer. No installation is necessary of any of the executable (.exe) files; they automatically run when the program is launched. All the software here is open source, which means that many developers are making regular improvements; one just happened recently that has fixed some problem issues I had with certain discs not ripping. This tends to be a problem most often with classical SACDs, where the metadata character string for a particular file exceeds 256 characters — it happens a lot more often than you might imagine, and the ripping software originally couldn’t process files that exceeded that limitation. Fortunately, there’s a fix; go to page 142 of the HiFi Haven thread; midway down, click on the link EuFlo’s GitHub repository, and scroll down to the bottom of the page. Choose the -99 link that matches your operating system. Extract the files, then delete the “SACD_Extract” file from your existing software folder and replace it with the new one you just downloaded. So far, everything I’ve ripped has worked perfectly with the new executable file.

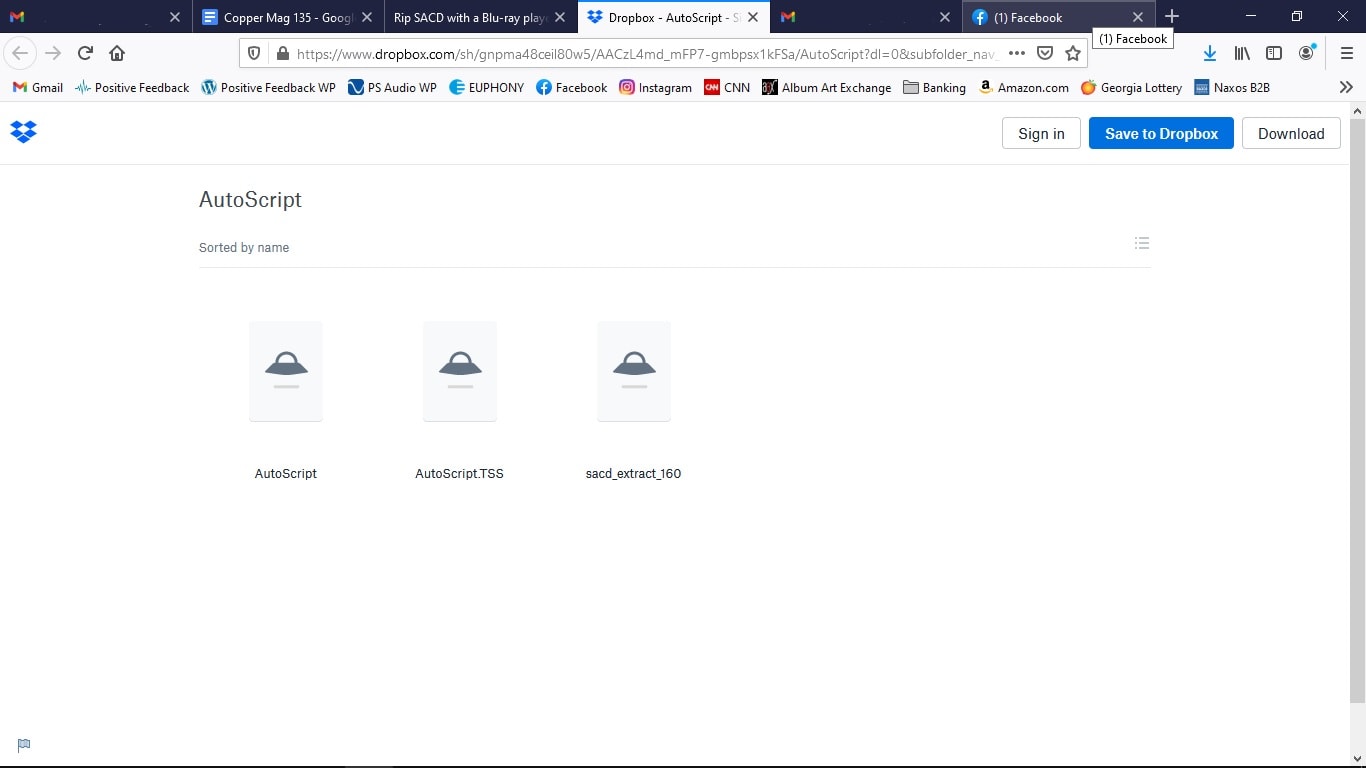

The last physical thing you need is a USB flash drive; preferably at least 4 GB, though the files you’ll be loading to it are fairly small. The flash drive should be formatted as FAT 32 (MS-DOS) or NTFS, with Master Boot Record (MBR) chosen as the partition scheme. This part is VERY IMPORTANT to the overall success of the process. I’m running Windows 10, and I’m not completely certain that it will allow you to format a flash drive using MBR — I wasn’t able to get any of this working properly until I used a Mac to format the flash drive as MS-DOS and MBR, and now it works with both Macs and Windows. After formatting your flash drive, go to page 2 of the HiFi Haven thread; midway down the page, there’s a reference to an AutoScript download. You’ll need to pick the link that pertains to your particular Blu-ray player manufacturer, and then extract the folder to a safe place on your hard drive. The folder will be named “AutoScript”; without opening the folder, copy it to your flash drive. Don’t open the folder under any circumstances — doing so could inadvertently alter the files within, causing them to function improperly, or not at all.

So, that’s everything you need; a functioning BD player properly set up, a properly formatted flash drive loaded with the AutoScript program, and the SACDExtractGUI program with the latest .exe update loaded onto your computer. I’ve done this on both Mac and Windows, and there’s one key setup difference. Windows applications and programs are automatically executable files upon opening, but that’s not necessarily true with Mac and Linux OS. The “SACD_Extract” file — which is the actual program that runs the process — has to be made a Unix executable file for Mac and Linux. Go again to page 15 on the HiFi Haven SACD ripping thread, to the same post that has the “Spoiler” links to the specific OS program files, and there are detailed instructions to easily make “SACD_Extract” an executable file using the Terminal function. I can’t honestly comment on Linux, but I know for a fact that it works with Macs.

All Blu-ray players have a USB port on the back panel, and some have one on the front panel as well; for some reason, the program seems to work more effortlessly when you insert the USB flash drive with AutoScript into the rear panel USB port (yeah, it’s much less convenient — sorry!). Connect the Blu-ray player to your network (if hard-wired) with the flash drive inserted, then power it on. It doesn’t need to be attached to a monitor, but you need to be able to determine the network address of the player. Since most networks tend to re-assign IP addresses with some frequency, it can be a bit of a task to keep up with your player’s current IP address. A handy smartphone app is FING, which will scan your network and identify your player’s IP address for you — it’s super-simple to use.

Then navigate to the location of the SACDExtractGUI program and double-click to open it; first of all, at the very top of the page and under “Program,” you’ll need to navigate to the location of the “SACD_Extract” executable file. There’s a test button and a prompt below will confirm that it’s working properly. Just below that, click the “Server” button, then enter the IP address of your Blu-ray player; the port will always be “2002,” and you can ping it and test it to make certain that you’re connected and the port is accessible. This program will work for extracting both the Stereo and Multichannel layers of an SACD, but be forewarned — that’s a ton of data, and ripping the entire contents of an SACD can easily run in the 4-plus GB range. For that matter, the stereo DSD files are very commonly 1 GB to 2-plus GB, so prepare yourself mentally for the long haul if ripping multichannel. In my experience, a typical stereo DSD extraction takes about 10 minutes or so.

The program offers multiple choices for ripping; you can rip the contents of the SACD to an ISO file — which is strictly for archival purposes, and can’t be played back without extracting the DSD files from it. Your other two choices are ripping as DSD Storage Facility (DSF) or DSD Interchange File Format (DFF). The difference is that ripping as DSF allows for the inclusion of metadata, and DFF does not, so if music library organization is important to you, DSF ripping is the only logical choice. So depending on what you want to extract, check “DSF” and Stereo and/or Multichannel. You might want to do a test rip; some DACs tend to insert a “pop” between DSD tracks. So you might want to also check the “Padding-less DSF” box, which tends to eliminate any problems of that sort. I’ve used it with all my rips, and haven’t noticed any issues of any sort.

The last thing you need to do is to navigate to your storage location, or wherever you plan on placing the ripped files for the short term. If you don’t browse to create a path for the Output Directory, the program will automatically place your ripped files into individual folders within the folder where the program is located on your hard drive. Just make certain that you have plenty of storage space available; I’ve ripped over 150 SACDs so far (in less than five days!), and ripping only the Stereo layers has already totaled almost 350 GB. I then transfer the files to another SSD that’s network-connected — surprisingly, the large files copy across my wired network very quickly. I then wipe them from my computer’s hard drive — at one point recently, I came within 1 GB of maxing out my computer’s M2 SSD drive, which wouldn’t have been good. And of course, you need to have some storage redundancy, just in case disaster happens and you lose a hard drive. You don’t want to have to go through this process again!

This surely goes without saying, but the ripping process is fairly labor-intensive for your computer. Not only is the laser drive of your Blu-ray player placed under a fair amount of stress, but it’s also helpful if your computer has a fairly robust processor with multiple cores, utilizes a solid-state drive, and is equipped with plenty of RAM. I’m using a fairly fast Intel Core i5, quad-core processor with an M2 SSD boot drive and 8 GB of RAM. It makes the process fairly effortless, but when an SACD rip is underway, my computer’s fan runs almost constantly and there’s a lot of buzzing and clicking — it’s obviously a pretty involved process.

By this point, if everything is a go, you’ll need to turn on the BD player again; because of the AutoScript on the inserted flash drive, the disc drawer should automatically open (I’ve noticed that it sometimes goes through this motion a couple of times — nothing to be worried about). Insert your chosen SACD, press the close button, and wait for the disc to load and show you the total disc playback time on the player’s display. If at any point, “WAIT” shows up in the display, something has gone wrong. But if the timing shows up okay, then touch the power button to power the machine down; when the machine display goes blank and the unit shuts down, remove the flash drive from the back of the machine. Then click the “Run” button on the SACDExtractGUI program; within a few seconds, the program should start, and you’ll see the disc ripping in the GUI display on your desktop.

As I noted above, if you’re only ripping the stereo layer of an SACD, it usually takes about ten minutes or so, and that’s for a hard-wired or wireless connection. And you don’t need to reinsert the USB flash drive with every rip; once inserted, it’s usually good for six or eight SACD rips. My experience is that the program tends to “lose its mind” after about six or eight rips, and the process is very specific to get back on track. If you go through the normal process and “WAIT” appears in the BD player display, a reboot of the player is required, and this can only be accomplished by physically power-cycling the unit by unplugging it from the power source and then re-plugging it. At that point, you also need to re-insert the flash drive; it’s basically just like starting over again, and the process has to be exact every time. 1) Unplug the BD player from the power source, 2) re-insert the flash drive, 3) re-plug the BD player to the power source, 4) insert the SACD, 5) power down the BD player after the total time shows up on the display, 6) remove the flash drive from the rear of the player, and 7) press the “Run” button on the extraction program. Follow these steps, and it works really effortlessly, and once you get the drill down, every single time.

It probably took me ten days to figure out how to get the very first SACD to rip; it was pretty much a combination of small errors and poor sequencing of events on my part. Probably the biggest hurdle for me was the whole “power cycling the BD player by unplugging it and replugging it” thing, which seemed really counterintuitive to me. And getting the flash drive with the AutoScript program properly formatted — this is vitally important. Also, if you’ve been ripping with a wired connection, and then decide to try wireless — the setup will revert to the wired IP address, which will have to be changed manually on the ripping program GUI. It really, really helps if your internet download speed is fairly fast; mine is only about 30 Mbps, and it works well with most everything, but don’t try running multiple devices simultaneously — your wife or significant other will end up getting kicked off the Wi-Fi signal, and if your situation is anything like mine, all hell will break loose!

I mentioned earlier that choosing to rip to DSF files is a great choice because it allows for adding metadata and images to the files. It’s a bit more difficult than editing the metadata with FLACs and other digital media, but I’ve found a really great freeware program, MP3tag, which works pretty effortlessly with DSF files. But it’s a little bit of a learning curve! So far, after about 160 ripped SACDs, I’ve pretty much discovered that you generally get most of the necessary metadata as part of the rip process, but it may need a little tweaking here and there. Some of the fields come up with incorrect or marginally correct information, but I’ve decided that having access to the music is the most important thing here, and if the metadata is less than perfect, I can live with that. You’ll definitely want to add album artwork to the files, and I’ve discovered by trial and error over a period of several years that after you drag the DSF files into MP3tag’s file name window, you need to use your cursor to highlight all the file names before you make any batch alterations to the tags. For example, when adding album artwork, you simply drag it into the artwork window (with all the tracks highlighted), then go to the top of the frame and click on the “Save” icon (it’s a floppy disk). Just keep the file names highlighted throughout the editing process, then click Save; that guarantees that everything is retained in your tagged information.

While there’s a lot of really great information at the HiFi Haven SACD ripping thread, it’s kind of pieced together in a patchwork manner, and takes a fair amount of dedication and desire to get things working. That said, I now feel pretty much like an expert of sorts at this — and it’s really gratifying to simply click a button and get really great DSD playback from my digital library without all the fuss. The sound quality is every bit as great as from a spinning disc — it’s darn near intoxicating! I’ve been listening to a ton of music that I don’t listen to as often as I should because of the added convenience factor, and I still stand by my previous declaration — DSD to me sounds so very much closer to analog than anything else out there.

Thanks to Mikey Fresh and everyone over at the HiFi Haven website for their dedication and perseverance in making this technology much more manageable for those of us who weren’t born computer geniuses. Oh, and in the three weeks since I spotted my working BD player at a Goodwill for $11, I’ve seen a couple more at about the same price, and they’re all over the internet. If you have any interest in this at all, have a fairly large library of SACDs and would like to try ripping them, it might be prudent to pick up a player or three just to have on hand. I know I will!

Header image: MSB Technology Universal Media Transport V.

Deko Entertainment: Moving Rock's Legacy Forward

When Gene Simmons of the band KISS said that “Rock is dead” in 2014, it sent shock waves throughout the industry. He later clarified his comments by saying that new bands “haven’t taken the time to create glamour, excitement and epic stuff” and that they lacked the ability to develop a real legacy. Recently, he added to these thoughts by commenting on how the current music business model is really stacked against the artist.

The team at Deko Entertainment would probably agree with most of what Simmons has said. That in part is why they founded their label. Deko was launched with the intent of providing a home to legacy rock artists who were continuing to make great music but couldn’t capture the attention of any major label. These are artists that they felt continue to have a vision and a story to tell.

Partners Bruce Pucciarello, Grammy award-winning engineer Alan Douches, and musician Charlie Calv have focused on traditional artist development and a more evolved approach to marketing and promotion, helping Deko quickly grow into an enterprise that very well might be the model for music moving forward. Their business has quickly grown from a handful of vinyl projects to full-on representation of existing and emerging acts, with a variety of offerings. Their roster includes bands and artists like Ten Years After, Cold Weather Company, Albert Bouchard and Joe Bouchard (formerly of Blue Õyster Cult), legendary drummer Carmine Appice and now Tiffany among others.

New platforms are about to be launched which promise to take things to another level. In the process, Deko Entertainment might not only change the label business, but it just might transform radio, streaming and every other outlet designed to help you discover great music.

We caught up with the team and talked about the label’s origins and where they see things going forward. The energy they bring to the conversation was simply infectious.

Ray Chelstowski: How did Deko get its start?

Alan Douches: Deko really started about 25 years ago. I was working with artists who I felt were making really great records, but couldn’t get a record deal. Through my connections, mostly through working with a lot of indie labels, I managed to convince Big Daddy Records to distribute us. Unfortunately we didn’t have the personnel or the capital at the time to really take advantage. As we tried to reboot this four years ago, it was more because “physical” (sales of physical media) had dropped off. Everyone had access to digital distribution. For perspective, 60,000 songs a day are uploaded to Spotify. That’s a wonderful world, except it’s too “noisy” and there’s no way for an artist to get [the] branding [they need].

That’s when we realized that there was a need for physical [media]. So Charlie and I got together and approached ADA [Alternative Distribution Alliance} for distribution. We weren’t going to just pick up an artist’s back catalog, press it and hope for the best. This is about teamwork, and the artists have to be able to give us some shows [and] have to be able to tour at least regionally, and we kinda kicked it off from there.

With the addition of Bruce [Pucciarello] we are looking at a bigger picture. [We’re] not just looking at established artists that need a home, but also new artists who want to identify with their brand. It’s not about just throwing it up on Spotify and getting a bunch of likes.

RC: Indie labels like Wicked Records seem to be focused on a specific kind of sound. Deko seems more open to variety. How do you determine who belongs on the label?

Bruce Pucciarello: Deko is an entertainment community, and our commitment is to be open-minded and supportive of all music and art. The “institutional” approach is fine for some, but we aren’t looking to corner a market or focus our artists to leverage a specific fan base. Maybe it sounds antithetical to the typical business model, but we are just building a positive artistic community, and in our community, we love all different kinds of music. We want to [put] our artists [in a place] to create, and then it is our job to get [them] out to the public in a fair and equitable way and make enough money to invest in their next project. We meet with our artists constantly and we are available to all of our artists whenever they need us. We are not a record company. We are a partner for our musicians.

RC: Does being a musician give you a better perspective on how things should operate?

Charlie Calv: It does because I’m very empathetic to the artists, I understand how they feel. I know that there are a lot of labels out there who will put out your product. But once it’s out it’s hard to get return phone calls or get people to return your emails. We on the other hand are really passionate about what we do and if we are going to take someone on we’re gonna work it and make sure that the artists are happy.

RC: Deko has really assembled some great bundle packages by artist. How do you determine what goes in to each offering?

CC: It kind of depends on the artist. You need to find new ways to monetize product. You’re only going to sell so many CDs; you’re only going to sell so many pieces of vinyl. [But] what else can’t fans get access to? Especially due to COVID. You’re not going to shows. You can’t pick up a poster or a T-shirt. Why not make [all] that available and bundle items together? You make it cost-affordable and you try to tailor it to the artist. The success we had with the Bouchard brothers (of Blue Õyster Cult) was obviously [offering a package with] the cowbell. That was a no-brainer. It’s really coming up with creative things that the artist and the fans will both like.

Albert Bouchard's Re Imaginos bundle with signed poster, CD and cowbell.

Albert Bouchard's Re Imaginos bundle with signed poster, CD and cowbell.

RC: Have you found that there is a sweet spot for pricing a bundle?

CC: We try to keep everything under $100. Then there’s shipping costs as well, which can become expensive. We are doing the 25th anniversary [edition] of the Guitar Zeus [album] with Carmine Appice. That’s going to be a heavy-ticket item. It will be four LPs, three CDs, a booklet, and a piece of jewelry that has Carmine’s logo on it. And the quality of this stuff is really good. That’s part of the beauty of having one of the partners in the company, Alan, being an award-winning mastering engineer. When we go in and remaster this stuff it sounds pretty awesome.

RC: Can classic rock radio become part of your future?

AD: I think that radio is going to need a really big reboot. They’ve been in need of that for a while because they just [haven’t] reinvented themselves. I think that we have to get back to the personalities. That’s what we [originally] fell in love with – which DJ brought us what music. My first label manager was initially a manager of a record store and as a freelance producer/engineer I would go to him and ask, “hey Mike, what’s gonna be hot?” He had that magic touch of being able to pick what was going to click. I didn’t read the “Heatseekers” [chart] in Billboard. Mike was in the store talking to kids and the record companies, and he knew what had a chance of making it. Maybe the next cool step for Deko is to have that person. I have someone in mind.

RC: With so much music being consumed through new channels, how are you looking at technology as a tool to drive the business forward?

BP: The best businesses come up with smaller pieces of effective technology to accentuate their specific business model. That leads to a flexibility they have that the larger companies can’t duplicate. I don’t think anyone else is doing that as much as we are.

AD: We just got our first beta version back of an ITV app that we are going to be porting over to Samsung and others. There are certain channels that will be designed for specific genres. But there will also just be storytelling, where you will see Tiffany followed by Cold Weather Company followed by Angel. And maybe it’s all because they have a really great story.

CC: With our [upcoming] Apple TV app/channel, we’re also going also be able to offer surround sound along with HD quality. The real audiophiles are going to love this stuff. If you’re an Albert Bouchard fan and you like the Re Imaginos record [a remake of the 1988 Blue Õyster Cult Imaginos album, which was originally supposed to be an Albert Bouchard solo album – Ed.], imagine having a couple of those tracks in surround sound!

RC: Which artists in your portfolio are you most excited about?

AD: I’m excited about all of our new artists and I think that Deko is really just getting started on this vision of an artist-centric place where you can create art again. I know that a lot of people are striving for that but I think we’ve got a good shot at it. We’ve got a good team and I’m looking forward to how we can present this to new artists.

RC: Record stores seem to be reimagining their spaces. How can a label help music get back to a place where the connection to the fan is more intimate?

AD: I have no problem with a record store selling socks or bandanas or coffee if we are promoting the art. Many record stores are putting in small stages and letting the in-store experience be part of the [overall musical] experience for their fans. We at Deko want to approach those mom and pops and help them get artists who will be entertaining, [and where] we aren’t just trying to push the hit single, but instead the [artist’s] whole story.

BP: “Farm-to-table” aptly describes a future vision and repurposing for the “record store.” I think labels need to take ownership and build community for each of their artists locally, with the record stores and the local independent [musical] instrument and [music] lesson centers. There is a natural synergy here that is often underutilized.

RC: When live music opens back up would you consider assembling a label tour?

CC: I’ve always been a fan of labels that do their own little mini-festivals and we actually had some conversations with some booking agents overseas before COVID broke out. From a human perspective, you create bonds for life at these festivals. We just started doing some live streams. Albert’s done Re Imaginos in its entirety and we’ll be streaming that. We have some other [things] planned [once] things open up because these guys wanna play!

RC: In addition to the new technology and broadening the artist roster, what’s next?

BP: We plan to onboard advanced technology from another industry, in order to streamline our merchandise sales and delivery systems. We are currently cultivating domestic and international partnerships that will benefit all of our artists and expand the Deko Entertainment portfolio.

CC: With some of the newer releases, we aren’t releasing the single and the album right away. We are going to release them as a mini-series or an EP where you’ll get three songs. Then we’ll release another EP. In the end, the culmination will be the double-LP or whatever it turns out to be.

We are just starting to cross-pollinate some of the acts so that younger artists have the opportunity to work and be mentored by some of these legacy acts that have seen it all; from songwriting to life on the road.

AD: When I was a kid growing up in the ’70s you sat there in that rocking chair with the vinyl gatefold open and headphones on and you took in every word and every note and you watched the [whole] picture unfold. You fell in love with it. I think we have a challenge in terms of how that [happens] now. We’re not ignoring technology. But it’s got to get more endearing [and] back to that love of the art. Even if it’s a small niche, if we can conquer it I’ll be happy.

Header image of Ten Years After courtesy of Rob Blackham.

The Dawn of Digital and Film Sound Sync: Tales from the 1980s

- A cell phone was the size of a walkie talkie and cost over a thousand dollars a month, since you paid per minute for both receiving and making calls.

- 3/4-inch U-Matic and high-speed Betacam 1/2-inch video cassette formats were the indie professional workhorse choices for production.

- Multitrack recording on analog 24-track 2-inch tape was the industry standard.

- Macintosh computers had monochromatic (black and white) screen displays.

- People who worked in film and people who worked in TV/video were not only in separate camps, but had sufficiently dissimilar technical skill sets that they belonged to separate unions.

- The use of computer software for editing was still in its infancy, so video editing still was rendered sequentially on tape. Unlike today’s digital video editing where edited clips can be saved and randomly assembled (non-destructive), editing on videotape fixes the sequence of shots, and changes cannot be inserted without redoing the previous edits (destructive).

- Transfers of film to video were commonplace, but transfers of professional video to 35mm film were so rare that only two studios in the US had the technical know-how and equipment to execute it.

- Sony had created the F1 PCM stereo digital audio format to show off its technology in a consumer configuration that sounded so identical to its super-expensive professional system that the F1 and 501 tabletop consumer units became big sellers and Sony had to eventually scrap its pro system.

- Japanese musical instrument companies like Korg, Roland, Akai and Yamaha began marketing floppy disc-based digital sampling systems that were keyboard-triggered and available to working musicians, as opposed to the Synclavier and Fairlight systems used by people like Sting and Peter Gabriel that cost over $75,000.

A Sony PCM-501ES digital audio processor atop a Sony Super Betamax video cassette recorder. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Oliver A. Masciarotte.

A Sony PCM-501ES digital audio processor atop a Sony Super Betamax video cassette recorder. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Oliver A. Masciarotte.

Only a few years out of film school at the time, I had been working on independent films, music videos, and documentaries to gain experience. The mid-1980s was a fascinating time for audio and video production. Prices for equipment that used digital technology had finally reached the point where the hardware became affordable for independent production budgets. While film and video were still in rival and presumed never-the-twain-shall-meet camps (the notion boggles the mind in 2021!), digital audio had made great strides towards commercialization into the high tech audiophile and low budget professional markets.

Although this was before hard drive storage for digital audio had become practical and tape was still the medium of the day, the first use of video cassettes as a storage medium for digital audio emerged with Sony’s PCM-F1 Digital Recording Processor, which used the Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) format, and was also sold as a tabletop consumer adaptor unit branded as the 501 ES, a similar unit which was also licensed to Matsushita/Technics. The PCM-F1 converted analog audio into 16 bit/44.1 kHz digital audio, but stored it as a video signal which could be recorded on 3/4-inch U-Matic, Betacam or VHS video cassettes. The video tape, made to hold not only standard stereo audio but full spectrum color video, was considerably more convenient, robust and capable of storing the digital info as binary code than the Ampex 456 or other industry-standard audio tape at the time.

Additionally, MIDI samplers that could store sounds on floppy disks and could be keyboard-controlled became available at reasonable and even budget prices for the first time. The Akai S612, Korg DSS-1, Emu Emax and Roland S-10 were a few of the better models.