Loading...

Issue 124

Octave Pitch and Other Notes

Shapes of Things

Art Goes on Record

Reel dancing! Mercury “Living Presence” stereo tape, catalog number MDS5-4. Not an easy one to find; this one’s from my collection.

Variable-speed cutting: Marie Hippolyte Rose making a record in 1878. From Sound and Hearing, 1965.

In 1974, they knew how to build receivers!

Nearfield listening at its finest. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Arthur T. Cahill.

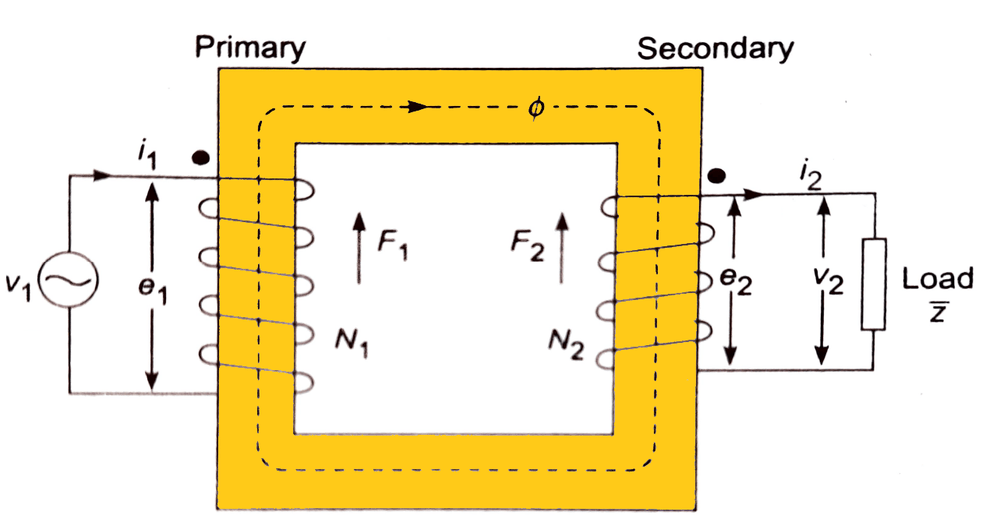

We’re still trying to figure out how this thing works. From Audio, July 1977.

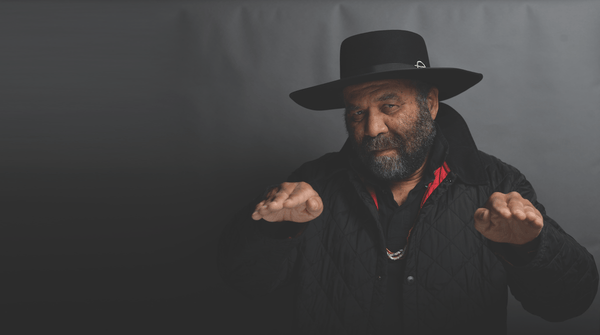

Walter Schofield of Krell Industries, Part Two

In Part One (Issue 122) we interviewed Krell Industries’ Walter Schofield about his early audio career, some of the landmark products he worked on, his ideas about the return of audio shows and more. We continue the interview here with a focus on Walter’s current work with Krell.

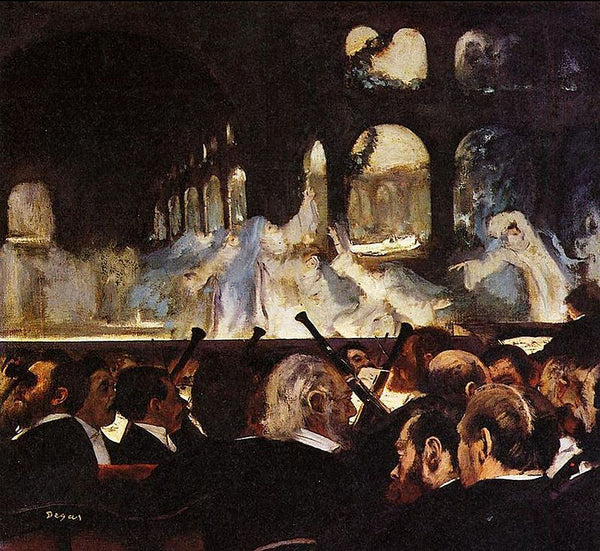

Don Lindich: My first experience with Krell was in the late 1980s at a high-end audio store in South Florida, where a Krell KSA-100 amplifier was driving a pair of Apogee Caliper speakers. The source was a SOTA Star Sapphire turntable playing highlights from Bizet’s Carmen from a Deutsche Grammophon LP. To this day it remains one of the best, most pure-sounding audio demonstrations I have ever witnessed, and that I remember it in such detail over 30 years later speaks to that fact! That Krell KSA-100 drove the notoriously difficult Apogee ribbon speakers effortlessly.

That Krell KSA-100 was a Dan D’Agostino design, and for a long time the names Krell and D’Agostino, both Dan and Rondi D’Agostino, were practically synonymous with each other. (Both were ousted from the company in 2009 after a takeover, and Rondi eventually returned to Krell. Dan is now president of Dan D’Agostino Master Audio Systems.) Since then, the company has gone through many changes. Given the company was once so intimately associated with Dan and his design ethos, what is the current identity for Krell? How have things changed since his departure?

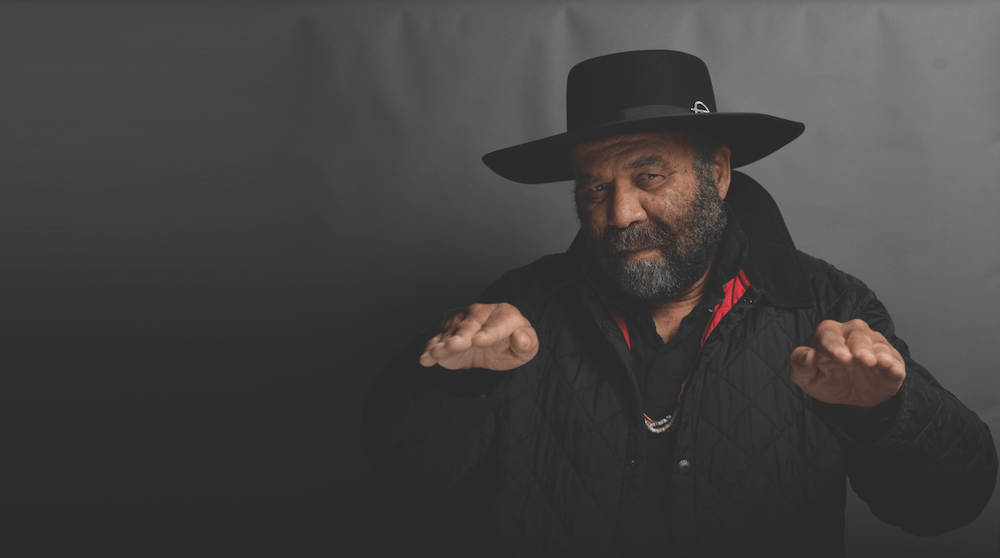

Walter Schofield.

Walter Schofield: David Goodman, our current director of product development, has been with Krell for 33 years and has been responsible for many of the company’s proprietary technologies.

Our design goals are: unmatched performance, and products that are elegant in appearance, with a compelling array of features including network connectivity.

For more than three decades, Dave has been instrumental in the continuous improvement in sound quality and capabilities of Krell’s entire product line. Additionally, he designed Krell’s critically acclaimed K-300i integrated amplifier. During its development he was able to substantially reduce the output impedance, while discovering a technique for greatly reducing harmonic distortion, resulting in a much more organic and natural sound.

Blast from the past: 750MCX mono power amplifier, circa 2000s.

Applying the techniques he learned in developing the K-300i, Dave’s engineering tenacity and innovation resulted in Krell’s current XD Technology. XD stands for “Xtended Dynamics, Dimensionality and Detail.” This resulted in the creation of Krell’s new XD Series of amplifiers, as well as the ability to retrofit current Krell products with XD technology.

After earning his BS in electrical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, David Goodman began his career with Sikorsky Aircraft as an avionics test engineer. He then joined Krell as a staff engineer, and soon becoming manager of engineering. Goodman has grown with the firm for over three decades.

Dave currently supervises a team of engineers in the concurrent development of multiple Krell products. His design experience includes responsibility for the electrical, mechanical and software design of every aspect and type of product that Krell manufactures.

He’s the co-inventor of Krell’s Sustained Plateau Bias technology, the forerunner of Krell’s proprietary iBias technology, which Dave has implemented throughout Krell’s current and forthcoming lines of amplifiers. iBias enables an amplifier to operate at the optimal level of Class A power without the excessive heat or power consumption normally associated with typical Class A designs.

K-300i integrated amplifier in silver and black. ($7,000 – $8,000 depending on configuration)

DL: How do today’s Krell amplifiers differ from such models of the past and how have they been improved?

WS: The implementation of iBias was a big step forward in Krell amplifier design. Krell’s history is rich with breakthrough Class A amplifiers that have helped build the company’s legacy of offering what we feel to be the best-sounding amplifiers available. Many audiophiles have considered Class A technology to be the best-sounding operating state for amplifiers, however, it has fallen out of fashion because of recent demands to reduce power consumption and heat in home electronics products.

Krell took this as a challenge. The result was iBias, a patent-pending circuit that delivers Class A operation without the excessive heat and wasted energy of conventional designs. What we hear is sound that is open and unconstrained, in a manner that rivals the true sound of voices and instruments.

Plainly stated, Krell feels that Class A designs are the most musically accurate circuit topology available. They do not suffer from the inherent distortions that all Class AB amplifiers experience. In a traditional Class A design, the output transistors conduct full current at all times regardless of the actual demand from the speakers. Often, only a fraction of this power is needed to reproduce an audio signal at normal listening levels. The rest of the power is dissipated through the amplifier’s heat sinks, producing large amounts of wasted heat. With Krell’s iBias technology, bias is dynamically adjusted, so the output transistors receive exactly as much power – but only as much power – as they need. The circuit works even at extremely low signal levels.

Solo 575 XD mono power amplifier ($12,500).

Previous efforts at using a “tracking” bias to accomplish what you could call “sliding bias Class A operation,” while effective, only measured the incoming signal and set bias levels from this information. iBias significantly elevates the effectiveness of previous designs by calculating bias from the output stage and output current. This seemingly small change in topology results in a dramatic improvement in sound quality, especially midrange richness and purity.

XD is another important technology. It was introduced in2018 with the K300i integrated amplifier and subsequently rolled out in all Krell amplifiers at the end of 2018 through 2019. The reviews and customer comments have been exceptionally positive.

During the development of the K-300i we discovered we could achieve substantial sonic improvements by lowering the output impedance below traditional norms. The improvement was so substantial we decided it deserved its own, unique “XD” designation. But it was no simple matter to implement. Lowering the output impedance affects the amplifier’s stability and transient response, so each stage prior to the output stage had to be re-tuned to work optimally with the lower output impedance. One of the advantages of lower output impedance is that the amplifier exerts more control over the loudspeaker drivers, and damps unwanted vibrational modes, allowing a more accurate reproduction of the original signal.

DL: Do you get a lot of repeat business from owners of vintage Krell products? And are there any differences between a Krell purchaser of yesterday and today?

WS: The customers of today and yesterday are similar in that they seek the best-available sound quality. That said, in addition to our traditional retail business, we’re getting more business from custom integrators.

DL: Krell has several product lines, though it is best-known for its amplifiers. Tell us about your other products.

WS: In addition to mono, stereo and multi-channel power amps and stereo integrated amplifiers we offer our Illusion and Illusion II preamplifiers, Foundation 4K Ultra HD Processor for A/V systems, our Vanguard Universal DAC Source, a 4K HDR switcher.

Illusion preamplifier ($16,500).

While some products may have been on the market for an extended period, we are consistently updating and upgrading them.

DL: What is your most popular product, and why do you think it has achieved that status?

WS: The new K300i is by far our most popular product, likely because it is the first one to incorporate our XD technology (the XD nomenclature is not added to the K300i, but it’s in there). It’s also our entry-level offering, yet we feel it sounds like a much more expensive product.

DL: Home theater is a notoriously difficult area for ultra-high-end manufacturers like Krell to compete in, due to rapidly-changing technology and features like Dolby Atmos and different forms of HDR being introduced seemingly every year. For the manufacturer, it is hard to spread the development costs required when the product doesn’t sell in mass-market quantities. An expensive home theater processor can become obsolete very quickly. For example, your own Krell Foundation 4K Processor, while highly regarded, does not have Dolby Atmos, a feature that is becoming a must-have in the premium segment. Do you have a strategy for competing in the home theater category and keeping up with rapidly-changing technology?

Foundation 4K surround processor ($8,250).

WS: We have three choices – one, to not manufacture preamp/processors at all and leave that to larger companies with more resources; two, to partner with a company that we can work with to enhance their offering(s); or three, to design such products in-house. We have two in-house Dolby Atmos/DTS-X pre/pros designed and at the ready. However, as you pointed out, they can become obsolete very quickly.

Krell is looking into option two, but we will only work with an OEM/ODM (original equipment manufacturer/original design manufacturer) partner if we can truly enhance their products to achieve the sound quality that we require of a Krell component. Stay tuned!

DL: Are most of your customers 2-channel or multichannel listeners?

WS: The split is about 60/40, leaning to 2-channel reproduction. However, the home theater segment has been growing consistently over the past few years.

DL: Where are Krell products manufactured?

WS: We source the majority of our components in North America, and assemble everything in our Orange, Connecticut factory. We still source small bits from Asia; however, our focus is to bring all component manufacturing to North America with all future products, of which we have 23 introductions planned between Q1 of 2021 and the end of 2024.

DL: Have you encountered supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic?

WS: Unfortunately, yes. Our business has been trending up since the end of 2018, and we have not been able to keep up with that growth and have underestimated our needs for the components that go into Krell products. As a result, our suppliers have been scrambling to get our needs fulfilled as they ramp up for us. Combine that with parts availability issues to both them and us because of the pandemic, and it has created a perfect storm that we are not fond of.

We have always been a just-in-time manufacturer [a manufacturing method that requires quick delivery of parts and maintaining lean inventory levels – Ed.] and our lead times had been cut to two weeks in 2018 and 2019, but with our vastly increased sales and the shortages, we are running a bit behind. Our backlog has never been larger, a good issue to have in a way; however, we are asking our dealers and retail partners to be patient as we realign our resources. It’s getting better!

Illusion II preamplifier ($7,700).

DL: What does your dealer network look like these days?

WS: Many US dealer partners are committed to us, however, we have a way to go to rebuild Krell back into the iconic brand that reflects its technologically-leading nature. Our international partners feel the same: very committed to our growth; however, we will be making changes to that network as we have seen some recently-appointed partners exceed our expectations.

DL: What are the qualities you look for when establishing a Krell dealer?

WS: A sincere desire to bring the very best sound to their customers is a big one, as well as their commitment to customer service. Krell has not been the best at customer support; however, we are getting better and working diligently to enhance our customer support to the highest level in the industry. There is a long road ahead, but we like where we are and where we are heading.

DL: Do you plan on expanding your dealer network?

WS: Expansion would not be a correct term – we are seeking to reconnect with our legacy partners, and we’ve made great strides over the past two years. As we become a better partner, we expect the growth of our network to naturally occur.

During the pandemic, Krell has assembled a plan that addresses all aspects of our business, and the future looks very bright.

DL: Sadly, we do not have as many hi-fi stores as we used to, and the market is shifting to e-commerce or a blend of e-commerce and brick and mortar. For a company like Krell with premium products that are best seen, touched and heard to drive sales, how do you operate in such an environment?

WS: Our goal is to primarily partner with brick and mortar and custom integrators. That said, there are a couple of e-tailers that hold to manufacturers’ pricing policies and have a wide audience. In our opinion, their reach brings top brand names to so many end users, which we’ve seen to enhance sales for all partners, so we will not rule out potential partnerships in this area.

DL: If someone wants to purchase a Krell product but there is no dealer in their geographical area, can they still be accommodated?

Our dealer partner agreements are sacred to us, and if a customer contacts us, we will put them with our nearest partner in their geographic region. If the customer needs to hear a product and is nowhere near a dealer, we recommend they contact our sole online partner.

DL: What do you see as the future for Krell?

Krell has embarked on a mission with renewed vision, the enthusiastic support of a fully-engaged engineering department, and enterprise-wide support to develop as many new, technologically-advanced products as possible. Revenues were not only dramatically increased in 2019 and 2020; a plan was enacted to ready multiple product introductions to satisfy the pent-up demand for Krell products. We’ve also implemented infrastructure enhancements for customer service, manufacturing and operations.

We’re also planning marketing initiatives to reach a wider audience including enthusiasts around the globe, as well as high-net-worth individuals. Krell recognizes the necessity in reaching wide audiences of various age groups who are not aware that high-quality immersive music and theater experiences are available in their homes. Krell’s retail partners also recognize the iconic nature of the brand and are eager to play their integral role as well. I believe we are far from realizing our full potential.

AES Show Fall 2020, Part Two

I’d like to commend the Audio Engineering Society (AES) for the depth and choice of topics that online attendees of October’s AES Show Fall 2020 were offered. The tent-pole attraction was unquestionably the “7 Audio Wonders of the World” series, which gave virtual studio tours of some of the audio world’s best facilities. The series kicked off with a tour of Skywalker Sound. Let’s look at more of what AES 2020 had to offer.

Galaxy Studios Tour

The second stop on the “7 Audio Wonders of the World” tour took us to Belgium, home of Galaxy Studios. The brainchild of musician/producer Wilfried Van Baelen and his brother, engineering design whiz Guy, Galaxy Studios is the inventor of Auro-3D immersive audio processing and a prime example of how innovative engineering can influence aesthetic imagination.

Galaxy Studios took its name from the custom Galaxy analog organ that Guy built for his brother more than 40 years ago to take on concert tours. Envisioning a self-contained studio where Wilfried could create, record, and experiment with music and sound without time constraints, Wilfried and Guy built the original Galaxy Studios in 1980 over a chicken coop on family owned-land. Within one to two hours from Paris, Amsterdam and Cologne, Galaxy’s reputation for cutting-edge gear, excellent sound and the demand for Wilfried’s finely-attuned ear made the initial studio a success. However, Wilfried wanted to take the concept to the Nth degree and in 1990 a greatly expanded facility, designed by Guy, was launched.

Comprising 15 separate concrete bunkers all suspended on a series of isolation springs (each bearing over three tons of weight), the Galaxy Studios’ rooms each have a specially-designed acoustic environment separated by multiple 330-lb. doors, resulting in an isolation value of greater than 100 dB between each room at < 3 Hz (in low-frequency isolation) – making these among the most silent rooms on the planet.

The Van Baelens designed every Galaxy room for maximum interactivity. Wired cable connections and special 4-1/2-inch soundproof glass panels (weighing more than a ton each) allow for a clear view line of sight through multiple rooms. Guy needed to design a special hydraulic lift machine to mount each of the panels.

The Galaxy Studios immersive audio theater.

Galaxy’s Auro-3D signature is probably Wilfried’s crowning achievement. Auro-3D is an immersive sound mixing system that processes the direct overhead “Voice of God” channels (as the surround-sound height channels are known), to seamlessly blend with an immersive audio system’s 7.1 or 9.1 front and rear left and right, and center channels. Auro-3D creates a correct, coherent sound field for the vertical axis for a natural sonic 3D effect, as opposed to other virtual audio systems that only function on the horizontal axis. All of Galaxy’s control rooms have Auro-3D capability.

Wilfried explained that Auro-3D maintains the integrity of the surround mix across all types of surround monitoring systems when collapsed to smaller-channel-count formats such as 9.1, 7.1, 5.1 or even stereo.

Galaxy also commissioned the first custom console built for 3-D audio from AMS Neve in 2007. It has 500 channels (!) with 96 kHz sampling rates and 250 channels with 192 kHz sampling rates. Galaxy prefers custom built Genelec monitor speakers for their Auro-3D rooms. Their 3D-audio cinema mixing room comprises a 180-seat theater and dubbing stage with a 45 foot by 9 foot 4K projection screen and Meyer Sound loudspeakers. The console is on a platform with a hydraulic lift that allows it to be elevated or sunk to floor level, enabling the mixing engineer to hear the mix literally from different locations to assess what the 3D mix would sound like from a theater’s floor or mezzanine, for example. The cinema mix room’s co-designer was former Galaxy Chief Technology Officer Robin Reumers.

Galaxy’s mastering room was completed in 2002. The console offers +30 dB headroom with an astonishing zero (!) measurable distortion. Bob Ludwig was reportedly so amazed at its design that he had it re-created at his Gateway Mastering Studios.

Guy Van Baelen also designed Galaxy’s innovative energy-neutral HVAC system. Pumps and a boiler powered by running groundwater fuel an electric generator and the air conditioning and heating systems; it is a green-energy engineering marvel.

There’s no lack of space at Galaxy Studios.

The incredible architectural and acoustic design aspects of Galaxy Studios notwithstanding, their control rooms all contain pretty much everything one would ever need equipment-wise, with custom AMS Neve consoles (including the first Capricorn console ever built), Neve preamp racks, Tektronix, Fairchild and Pultec vacuum tube compressors and EQs, state-of-the-art digital gear, and a collection of mics from Neumann, Telefunken, AKG, Beyer and Schoeps that would be the envy of any studio. They also have 48-track Studer analog tape recorders, digital tape and hard-drive recording machines, Pro Tools HDX digital workstations, and a full complement of film and HD video equipment.

Galaxy also houses Wilfried’s personal keyboard collection, including Guy’s hand-built analog Galaxy and digital Atlantis organs and a mind-boggling selection of vintage Roland, Yamaha, Moog and Oberheim synthesizers and grand pianos. They also have an extensive selection of vintage and modern guitar amps.

Galaxy’s superb acoustic environments made it the studio of choice for George Massenburg to record his Superior Drummer samples collection and for Yamaha to record the piano samples for its electric piano models and synthesizers. Artists such as Santana, Rammstein, Mary J. Blige, Lauryn Hill and others have recorded over twenty platinum records at Galaxy. And now, Galaxy’s Auro-3D technology has made the facility a natural for audio production for movies.

George Lucas used Galaxy for Red Sails, the first movie mixed in 3D, in 2011. Galaxy has a relationship with DreamWorks and has facilitated complex mixes for blockbuster features like Jumanji, Spider-Man 2, John Wick, Transformers, Blade Runner 2046, Jason Bourne and countless others.

In keeping with cultural tradition, Galaxy also has its own band of Belgian beer available at its fully stocked bar. Sounds like an unforgettable European experience!

The Trinnov Optimizer, and JBL 3-Series MkII Studio Monitors

Dale Pro Audio hosted a number of online product showcases including two from Trinnov Audio and Harman/JBL that addressed the issues of monitoring and mixing in sub-optimal environments.

Trinnov’s Optimizer software is used in its Altitude32 and Altitude16 audio/video preamp/surround processors. Working in conjunction with DSP-equipped loudspeakers, Optimizer measures the acoustic response of a particular room and the placements of the speakers in the room and uses proprietary algorithms to calculate, calibrate, and fine-tune the speakers for time, level, and EQ alignment as well as correct phase and group delay, with optimization of all the active crossovers in a system. The PC-based units can store multiple rooms, mix positions, and different engineer preferences in memory. Engineers who often travel to work on projects in remote locations or even mixed in residences or places other than a professional studio might find Optimizer invaluable.

Trinnov Altitude 32 Reference Immersive Audio Processor.

Harman’s latest JBL 3-Series MkII compact studio monitors address the need for such products because of the growth of home studios. Harman’s David Tewksbury explained the engineering behind the 3-Series MkII, much of which is based on JBL’s M2 Master Reference Monitors. 3-Series MkII loudspeakers are specifically designed to deliver a wider and deeper “sweet spot” in less-than-ideal listening situations, and deliver transparent sound at higher output levels. These attributes also make the 3-Series MkII a good choice for mixing immersive audio on a budget.

JBL 3-Series MKII loudspeakers and subwoofer.

The Village Tour

While Skywalker Sound and Galaxy Studios’ gear, technology, and architectural achievements create a serious “wow” factor, West LA’s The Village, number three on AES’s “7 Audio Wonders of the World” tour, has a mojo that comes from an alchemy of artistic vibes, their rock and roll recording aesthetic, and an uncanny streak of lucky breaks and timing.

The Village was founded in 1968 by Hormel meat packing heir Geordie Hormel as a private studio (later to become the current Studio A). The Village went commercial soon after, giving birth to landmark recordings like the Rolling Stones’ Goat’s Head Soup, Aja by Steely Dan, and Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves. Manager Tina Morris recalled that Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers decided to become a band after a jam session in Studio A, and they went on to record Southern Accents there.

Studio B has also been the site of many hit records including Supertramp’s Breakfast in America, Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage, and albums from artists such as Pink and Miguel. The studio’s many film and TV mixing projects include Crazy Heart, The Hulk, Finding Dory, and Nashville.

The Village’s largest room, Studio D, is best-known for being built at the request of Fleetwood Mac in order to record Tusk. Other artists preferring Studio D include Eric Clapton, Weezer, Elton John, Sting and Selena Gomez. Bradley Cooper’s A Star is Born and its Oscar-winning “Shallow” was recorded in Studio D, and scenes of Cooper’s and Lady Gaga’s performances were filmed there.

The Village’s Studio D control room.

The smallest room, Studio F, is used mostly for overdubs, voiceovers and podcasts. Even so, Studio F fans include Lady Gaga (The Fame), Janet Jackson (Danita Jo) and Melissa Etheridge. It also serves as a control room for the adjoining Moroccan Ballroom, which is used to host and record live events, streaming concerts, and private parties.

The equipment in the studios sport Neve 88R and Avid S6 consoles (with a vintage Neve 8048 in Studio A) and all have Pro Tools HDX digital audio workstations, Ampex ATR 102 recording decks, Augsberger speakers, and a host of vintage and modern outboard gear.

Built in a former Masonic Hall, The Village’s rooms are key to its funky vibes. The Tahiti Booth (named for its tropical decorations) is a large isolation booth built for Stevie Nicks, and is equipped with a movable ceiling and an echo chamber copied from Capitol Studios. The aforementioned Moroccan Ballroom has a Middle Eastern décor and it inspired John Mayer’s writing and recording of Continuum as well as Coldplay’s “ A Sky Full of Stars.” Chris Martin’s piano part was played on Oscar Peterson’s personal 6-foot Steinway baby grand piano located in the studio.

The old linoleum tile floor and multiple reflections inherent in the Moroccan Ballroom and in Studio D give them a unique character that has become part of the highly sought “Village Sound.” In a Q&A with The Village’s owner, Jeff Greenberg, Tina Morris, and producers T-Bone Burnette, Larry Klein, and Ross Hogarth, the latter three waxed rhapsodically about the unique sound of The Village. One of the techniques deployed by both Burnette and Hogarth was to set up drums in front of the live room and open a door to leak out into the larger Studio D room and mic it as an echo chamber. Burnette also cited Studio D as creating the sound of his Grammy Award-produced Raising Sand by Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, The Union by Elton John and Leon Russell, and the soundtrack for O Brother Where Art Thou?.

Hogarth and Klein explained how the vibe and history of The Village was inspiring for Hogarth’s work with Van Halen and Keb ‘Mo and Klein’s with Shawn Colvin and Joni Mitchell – which was so crucial for creating the intangible magic that was impossible to replicate in a plug-in.

Greenberg also related how he was approached in the early 1990s by Hormel’s daughter to take over and restore The Village. Once Geordie Hormel relocated to Arizona, it fell to Greenberg, with the help of legendary producer Al Schmitt, to bring The Village back to its former glory. However, The Village’s close association with classic rock bands became a marketing albatross with young grunge and alt-rock bands who didn’t want to record “where their parents’ music was made.” Greenberg credits Billy Corgan with bringing street credibility back to The Village when the Smashing Pumpkins recorded their multi-platinum Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness there.

In the final AES Show Fall 2020 installments we’ll cover the highlights of the final week and talk about the other stops on the “7 Audio Wonders of the World” tour, including Blackbird, Abbey Road Studios, Capitol Studios, and United Recording in a separate article for a bang-up conference finale.

Four Classic Holiday LP Reissues From Sony Legacy

We’re taking a break from the usual new release record review format this issue to focus on some holiday classics, just in time for the holiday season. My wife (heretofore known as “The Boss”) deems it a strict protocol that the house gets decorated for Christmas the day after Thanksgiving, so mid-November is traditionally about the time that holiday music starts pouring over the airwaves at my house, anyway. Actually, it’s a bit worse than that this year, in particular; I just had a surgical procedure done on my elbow that precludes me from lifting anything (heavier than a pint glass, nudge, nudge!) until very close to New Year’s’ So the Christmas tree and all the boxes of decorations have already been brought out on November 1st, prior to my procedure. It’s definitely surreal, almost like being at home, but also like being at just about any department store this time of year.

Gabby Gibb (no relation) of Sony Legacy reached out to me with an offer of new 180-gram vinyl reissues of ten classic Columbia/RCA and associated label Christmas albums from a range of artists like Johnny Mathis, Andy Williams, Elvis, and so forth. Always willing to prostitute myself for the offer of promotional vinyl, I jumped at the chance, and chose four titles that played virtually nonstop in my home as a kid in the early sixties. I still have this kind of nostalgic memory of Christmases from long ago, although, if truth be told, it was nowhere nearly as idyllic as my memories would have me believe. I’m kind of like an android who’s had my memories programmed into my storage banks, but as time has gone on, definitely has begun to question the validity of those memories. Regardless, hearing artists like Johnny Mathis and Elvis sing classic Christmas tunes really helps to keep me believing that those memories were (are) real.

I grew up in a fairly spartan setting in a small, rural North Georgia town, but one thing we did have was a fairly large — if also, fairly old — Philco tube amped stereo console. Which produced surprisingly great sound, especially from the built-in FM tuner and from LPs. My mom had a pretty decent collection of LPs from the fifties and early sixties, and the holiday season had her pulling out records from Johnny Mathis, Elvis, Perry Como, and Andy Williams, among others. While over the years, my tastes in music veered heavily into the rock and roll direction, I still find the Christmas music of my childhood very comforting. So I chose four of the available Sony Legacy LP titles that are either exact replications of music I’m infinitely familiar with (Johnny Mathis, Perry Como), or are collections (Elvis, Andy Williams) that incorporate much of the music from the classic LPs of yore. In retrospect, I probably should have chosen the Phil Spector album along with these, as it (with Elvis, of course) would have given my review a little bit more rock and roll street cred. Maybe next time!

Although these releases are 180-gram LPs, that are (from my observations) pressed on decent vinyl, they all retail for somewhere in the neighborhood of about $27 each — these are not super-premium releases, and the packaging definitely reflects that. The sound quality was consistently good across the board, although there’s no clear information regarding the provenance of the source tapes for the pressings. The LPs drop-shipped from a location near Nashville, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they were also pressed at that facility. So, 1) I’m pretty certain they’re probably not AAA (strictly all-analog throughout the chain) pressings, and 2) I have no way of determining where the LP pressings were sourced from. In this day and age of most LP pressings being sourced from digital masters, that’s pretty much come to be expected, anyway. The LPs had uniformly very clean and glossy surfaces, and exhibited very little surface noise.

The other area in which the LPs fell a bit short of super-premium territory was in the packaging; the sleeves are printed on substantial and fairly glossy paperboard that’s of decent weight, but the cover images are obviously sourced from digital scans, and are not particularly of the highest resolution; the Johnny Mathis and Elvis albums were much better in this respect than the other two. A couple of the LPs had very slight warps that didn’t impact playback too much; I use a record clamp, so the warps were generally only noticeable on one side. Pressing plants need to not use the “shrink wrap of death” that often assists in warpage more than any other single factor; I use a razor knife to open LP jackets, and even I had difficulty getting the plastic wrap off these new LPs. Regardless, it’s still really great and nostalgic to have the LPs here in my collection after all these years.

All my listening was done using my Pro-ject Classic turntable setup with its Hana SL moving coil cartridge, playing through the PrimaLuna EVO 300 tube integrated amp (EL 34 tubes!) and my Zu Omen loudspeakers. Let me tell you, nothing helps ring home the holidays like classic performances over tube electronics! I’ve heard most of these performances countless times, and in a variety of formats, but in general — and despite a few hiccups here and there — I don’t really think they’ve ever sounded as great as they do on these new LPs. Happy Holidays, ya’ll!

Johnny Mathis — Merry Christmas

Johnny Mathis’s Merry Christmas is definitely — in my book at least — the ne plus ultra of classic holiday albums. Recorded in 1958, it was Johnny’s first and best foray into a holiday-themed album, and immediately gained instant popularity with the record-buying public. The album made it to number three on the US Billboard charts, going gold in the first year of release, and charted and sold very respectably worldwide, especially in the UK. Over the years, Merry Christmas has shown its continued popularity and staying power, going five-times platinum and selling over five million copies. Easily maintaining its position on the list of biggest selling Christmas albums of all times, the record has charted 28 different times over the years since its release.

Merry Christmas is a mixture of the sacred and the secular, with Side One featuring Johnny Mathis’ inimitable voice as he takes on classic Christmas pop tunes like “Winter Wonderland,” “The Christmas Song,” “Sleigh Ride,” “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” “Blue Christmas,” and of course, “White Christmas.” Nat King Cole might get the nod for “The Christmas Song,” and Bing Crosby for “White Christmas,” and who would deny Elvis the crown for “Blue Christmas,” but Johnny’s rendition of all three places him squarely at number two (for me, at least) on each of those tunes. And he imbues them each with his own special vocal stylings that distinguishes his version from those of the other classic Christmas crooners. “Winter Wonderland” and “Sleigh Ride” are definitive readings of each tune, and for me, if I ever feel the need to get somewhat weepy/nostalgic during the holidays, no one can touch the tear-jerk level he brings to “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” It really gets me, every single time.

Side Two is dedicated to traditional Christmas hymns, with Johnny once again offering near-definitive versions of “O Holy Night,” “What Child is This,” “The First Noel,” “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” and “Silent Night, Holy Night.” I don’t think anyone can approach Johnny’s heartfelt renditions of these sacred tunes; the level of power and emotion he instills them with just completely gets me in a way that isn’t quite the same with other performers. A long-time family favorite is Johnny’s version of “What Child is This,” where he powers through the sacred variant of “Greensleeves” with incredible emotion; upon hearing this song for the first time, my five-year-old daughter remarked, “you know, he really shouldn’t belt it out like that!” We’ve been laughing about that moment ever since. The only secular tune that interrupts an otherwise completely sacred Side Two is “Silver Bells,” the Ray Evans/Jay Livingston classic that was definitely my favorite Christmas song as a small boy. Of course, I don’t think anyone else’s version can touch Johnny’s for the very personal emotion reading he gives the song.

The 180-gram LP pressing of Merry Christmas was about as pristine as could be expected, with virtually zero surface noise, and nary a click or pop. Maybe it was partially due to that warm tube afterglow, but the sound quality was so off-the-charts good with this release, I’d swear it was taken from an analog master. This is a classic album, with classic readings of songs that are inimitably Johnny Mathis. Very highly recommended.

Sony/Legacy Recordings, 180-gram LP (download/streaming [24/96] from Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon Music, Google Play Music, Spotify, YouTube, Apple Music, Pandora, Deezer, TuneIn)

Elvis Presley — The Classic Christmas Album

The Classic Christmas Album was compiled in 2012 from two different albums; 1957’s Elvis’ Christmas Album (his first holiday-themed album), and 1971’s Elvis Sings the Wonderful World of Christmas. Elvis’ Christmas Album is the biggest selling Christmas album of all time, selling over three million records at the time of its release; a 1970 reissue of the same title was certified diamond (ten million units). Elvis has sold over 22 million Christmas albums — not too surprising, since he’s the single biggest selling artist of all time, having sold over a billion records worldwide.

Not surprisingly, the songs from the 1957 release are the real reason for getting this LP, but that’s not to say that the 1970 tracks are without merit; there are definitely some great tunes there as well. But the ’57 songs are much more well recorded; a youthful Elvis gives a much more enthusiastic performance, and there’s less of the Vegas headliner Elvis so in evidence in his later years. Probably part of the reason for this compilation’s song selection has to do with the makeup of the original 1957 sessions, which presented one side of secular Christmas songs, with the second side consisting of all sacred hymns — four of which weren’t really holiday-oriented at all. So this LP gives you the best of the 1957 sessions — which are absolutely great, and the real reason to get this LP — along with some 1971 filler. Which gives you some pretty entertaining, if not quite as energetic, performances of the music.

Side One kicks off with two tunes from the ’57 sessions, “I’ll Be Home For Christmas” and “Blue Christmas,” which I’d absolutely rate as the definitive performance of this tune. You then segue into an extended montage of 1971 Elvis, with tunes like “Winter Wonderland,” “The First Noel,” “Wonderful World of Christmas,” and “Holly Leaves and Christmas Trees.” Elvis gives serviceable performances here, and maybe he’s phoning it in, but trust me, the best of 1971 is still to come. The tune that makes the 1971 release absolutely worthwhile is “Merry Christmas Baby,” where Elvis seems much more invested in what’s going on, and there’s some really excellent guitar work from James Burton, including a scorching solo that’s the song’s centerpiece.

Side Two kicks off with the last of the 1971 sessions, the highlight of which is “If Every Day Was Like Christmas,” which highlights a really soulful lead vocal from the King, along with great backing vocals from the Jordanaires and the Imperials. We then shift back into 1957, where the rest of Side Two features the classic material from that first album, including rockers like “Santa Bring My Baby Back to Me” and my personal favorite, “Santa Claus is Back in Town.” Elvis is coming down your chimney, but he “Ain’t got no reindeer…got no pack on my back…Santa Claus is coming…in a big black Cadillac!” Elvis effectively delivers classics like “White Christmas” and “Here Comes Santa Claus,” and he also provides soulful interpretations of the two sacred Christmas hymns, “Silent Night,” and “O Little Town of Bethlehem.”

This LP package is probably the most perfectly realized of the four albums reviewed here; the cover artwork is really nice and crisp, with good color saturation, and there’s even a printed inner sleeve with song lyrics. The LP was almost perfectly flat, and the surfaces were pristine, with very little surface noise. Yes, there’s some filler here, but overall, Elvis’ The Classic Christmas Album is a worthy addition to your holiday collection. Recommended.

Sony/Legacy Recordings, 180 Gram LP (download/streaming [16/44.1] from Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube, TuneIn)

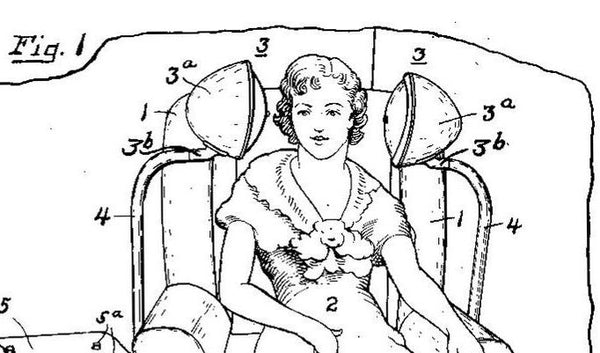

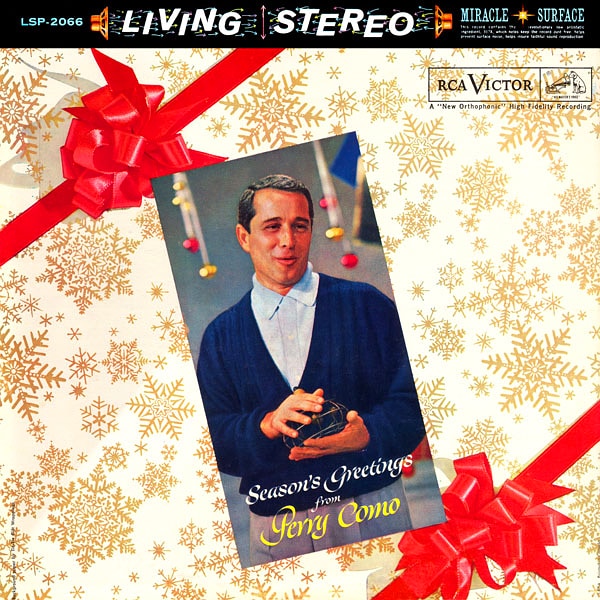

Perry Como — Season’s Greetings from Perry Como

My mom — and my wife’s mom — both loved Perry Como. As a teenager, I jokingly referred to him as Perry Coma, because his music might definitely drowse you out. Don’t let his seemingly complacent demeanor fool you; I’ve seen some videos of Perry Como from back in the day that lead me to believe that he was less of the mild-mannered, MOR crooner as he’s portrayed, and maybe a whole lot more of a ladies’ man. Regardless, I have definitely developed much more of an appreciation for his vocal stylings with holiday songs over the years, and his velvety-throated voice is a perfect delivery vehicle for all of the great songs here. Along with Johnny Mathis’ Merry Christmas, this 1959 album, Season’s Greetings from Perry Como, is the only other of the four LPs I received that’s presented in its original catalog form. The original RCA Living Stereo title was his first holiday album, and one of his first albums to be recorded in stereo. This new LP represents the first repressing of the album in over 35 years.

Side One is the more secular side, and kicks off with Perry Como’s signature holiday hit, “(There’s No Place Like) Home For The Holidays”; it’s an undeniable classic and a perfect song for the season, and shows up on countless holiday collections. He follows with really stirring renditions of “Winter Wonderland,” “Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer,” “The Christmas Song,” and “Santa Claus is Coming to Town.” Side One closes with Como’s version of Irving Berlin’s classic “White Christmas;” he’s in excellent voice here, and really gives Bing Crosby a run for his money on this track.

Side Two consists of mostly classic Christmas carols and hymns, and opens with a rousing “Here We Come A-Caroling/We Wish You a Merry Christmas.” Up next is an equally great “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,” which is then followed by the sacred hymn “O Holy Night.” The remainder of the album features Perry Como’s narration of “The Story of the First Christmas,” which features vignettes of the songs “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “Come, Come, Come to the Manger,” “The First Noel,” “O Come All Ye Faithful,” “We Three Kings of Orient Are,” and concludes with “Silent Night.” The entire album features backing vocals from the Ray Charles Singers, but “The Story of the First Christmas” really highlights their contributions. This is a great tune to share with your children.

Even though this album probably shows its age a bit more than the others here, Perry Como is in great voice throughout, and many of the songs here are classics. This LP is superb; the pressing was perfectly flat, while the surfaces displayed an almost indiscernible level of surface noise. Highly recommended.

Sony/Legacy Recordings, 180-gram LP (download/streaming [16/44.1] from Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube, TuneIn)

Andy Williams — Personal Christmas Collection

The golden voice of Andy Williams is almost right up there with Johnny Mathis in my memories of Christmases past; his music played a lot in my home as a child, and if it wasn’t his classic holiday offerings, it was “Moon River.” This LP, Personal Christmas Collection, was compiled in 1994 from his three Christmas albums on the Columbia label, 1963’s The Andy Williams Christmas Album and 1965’s Merry Christmas, along with three songs from 1974’s Christmas Present. Both of the sixties albums are undeniable classics; The Andy Williams Christmas Album made it to No. 1 on the Billboard charts upon release, reaching gold record status in its first year and eventually going platinum a couple of decades later. Merry Christmas would also reach the No. 1 position on the charts, also eventually going gold, and then later platinum. While his first two Christmas albums were mostly secular offerings that featured some of his most memorable holiday songs, Christmas Present was almost completely a collection of sacred music.

Personal Christmas Collection opens Side One with “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” which is far and away Andy Williams’ signature Christmas song; it makes it onto just about every collection of holiday crooners you’re likely to find. In January, 2020, it landed again at No. 7 on the Billboard charts, and became Andy Williams’ highest charting single of all time! The hits just keep on coming, with “My Favorite Things” — which is the subject of a fair amount of scholarly debate as to whether or not it actually is a holiday song — clocking in at number two on Williams’ list of most memorable songs. Regardless, he definitely made this song his own, and he definitely helped confirm its acceptance into the canon of secular holiday pop music. Following is another pretty great rendition of Mel Torme’s “The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting By An Open Fire)” — again, I’d easily rank Andy Williams’ version in the top five of classic versions. And he helped to popularize “The Bells of St. Mary’s,” a 1920’s pop song that never quite took off until Williams’ owned it in the sixties. The other big Side One hit is Andy’s take on “Winter Wonderland;” he has a very joyous, upbeat approach that rivals Johnny Mathis’ version on my list, and is definitely a worthy alternative.

Side Two of the LP opens with Williams’ take on “Sleigh Ride,” which is also a classically enjoyable rendition of the Leroy Anderson tune; the chorus chants “jing-a ling, jing-jing-a ling” throughout, and it’s a startling contrast to Johnny Mathis’ version. We also get fairly classic versions of “Silver Bells” and “White Christmas,” although the two other big highlights for me on this side of the album are “Christmas Bells,” which is Williams’ fabulous 1974 take on “Carol of the Bells.” Also, “Happy Holiday/Holiday Season,” the Irving Berlin/Kay Thompson medley that Andy Williams has made into a Christmas classic; his version is the one you generally associate with the tune. The classic sacred carols “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” and “Silent Night” fill out the proceedings.

The sound quality of Personal Christmas Collection was very consistently good, although the LP had probably the worst warp of any of the group, and there was a fair amount of surface noise on this particular pressing. A deep cleaning of the LP could help to rectify the noise situation. The record jacket image quality was also easily the worst of the bunch; the album cover image scan came from what must have been fairly low-quality artwork that was probably prepared for the much smaller CD format (the compilation came out in 1994, so there likely was never an LP release with correspondingly larger artwork). At the very least, when enlarged to LP size, the resolution is not at all good — there was probably little that could be done to improve upon the situation. Regardless, it’s very unlikely that you’ll ever encounter this LP in any other vinyl form, so I’d still grab one if you’re at all a fan. Recommended.

Sony/Legacy Recordings, 180-gram LP (download/streaming [16/44.1] from Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube)

The “Sound” of Speaker Cables: an Analysis

From time to time Copper offers guest articles from audio manufacturers and others in the industry. These viewpoints are their own and we publish them in the spirit of providing information from various perspectives, and encouraging discussion and even debate.

Max Townshend is the CEO of UK-based Townshend Audio, manufacturer of isolation devices, electronics and cables since 1975. The idea that different cables can sound different in an audio system has been a source of debate and controversy for a long time. Many audiophiles, and yes, manufacturers including Townshend, insist that different cables can make a difference in an audio system. Others dismiss this as marketing hype or snake oil. Here, Max Townshend describes an experiment for identifying differences between speaker cables.

To Ascertain By Measurement Why Various Speaker Cable Geometries Sound Different

ABSTRACT

This paper describes a simple experiment to identify the performance of a number of different speaker cables by measuring the “error” introduced into an audio system by each cable, i.e., the voltage drop between the amplifier and the speaker. The signals used are both white noise (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_noise) and music.

The results show that the principal factor determining the error of a cable is its geometry. Cables with very widely spaced conductors have the greatest error, closer-spaced conductor cables have less error, and very closely-spaced, flat conductor cables have the least, or near zero error. [Townshend Audio’s Isolda speaker cable is such a design. – Ed.] The results have been presented both visually and sonically at https://youtu.be/v11hmOE1Vcc.

The experimental method has been described in detail, to enable researchers to repeat the tests in order to verify the conclusions. The results of this experiment may embarrass those cable sound deniers who have hindered the advance of hi-fi for the past 50 years, and hence may allow the quality of high-fidelity sound reproduction to advance.

The Sound of Music – How and Why the Speaker Cable Really Matters

Researched and authored by Max Townshend, BEng.

“This investigation reveals that a major factor determining the ‘sound’ of a speaker cable is its characteristic impedance, Zo, which is determined by the cable’s ‘geometry,’ i.e, the way it is constructed. For a ‘perfect’ cable the Zo should match the impedance of the speaker load it is driving.” – Jack Dinsdale

Jack Dinsdale MA, MSc, sometime engineering professor at Cranfield and Dundee Universities, was co-designer in 1960 of the transformer-less transistor power amplifier, the first of its kind to approach “hi-fi” performance.

- INTRODUCTION

There is little doubt that speaker cables affect the sound of audio systems. Audiophiles have known this since the 1970s and there has been an ongoing debate ever since. Many explanations have been proposed as to why cables make a difference, but as of now there appears to have been no single consistent explanation.

This report describes a method of testing speaker cables by measuring their characteristic impedance; it then relates this to the way in which they are constructed. This method is consistent with electrical theory and computer simulation.

The paper goes on to show that speaker cables behave as transmission lines, and for correct (distortion-less) transmission of the audio signal from power amplifier to speaker the cable must match the impedance of the speaker load. This analysis clearly describes the cause of audible differences between a range of cables, and the examples included demonstrate this effect.

- MEASUREMENT

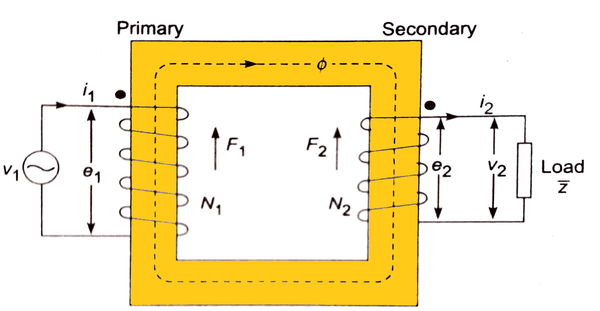

The measurement principle adopted here, shown in Fig 1. was to take a series of cables and examine the signal waveform voltage between the amplifier ground terminal (black) and the speaker ground terminal (black). Ideally, this signal should be an identical version of the signal between the amplifier ground (black) and the live terminal (red) with a reduced amplitude due to the low, but finite, resistance of the cable conductor. The frequency response over the audio band should ideally be “flat” between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. Any deviation from “flat” should be measurable and will most likely be audible as a tonal change in the audio signal.

A number of tests were carried out, using the following basic circuit, Fig 1.

Fig 1. Cable tester simplified circuit.

A standard 7 m length of each cable under test was connected as shown, with a power amplifier driving the amplifier end using a switchable white noise or music source, Fig 1. The load end of the cable was connected to an industry-standard 8-ohm two-way speaker dummy load, shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2. Dummy load.

In the first series of tests the signal voltage between the amplifier ground terminal Ga (black) and the speaker ground terminal Gs (black) was fed to a computer spectrum analyser and to a speaker via a suitable amplifier. This signal was chosen as it shows what is wrong with the cable; it is a very low resistance source and the ground reference is ideal. The results, Fig 3, show the frequency responses of a series of cables from 30 Hz to 20 kHz, together with their characteristic impedances Z0.

Fig 3. Frequency response of the test cables.

Each trace shows the difference in the voltage between the amplifier and the speaker of each cable. The frequency response should be as close as possible to the short circuit, trace 1 in Fig 3. The basically flat, level response at low frequencies between 30 Hz and 400 Hz is due to the resistance of the cable. The increasing rise in response above 400 Hz is due to multiple reflections caused by the mismatch between the cable characteristic impedance, Zo and the impedance of the load. Note that the load impedance varies between 4 and 25 ohms, which is an approximate match with the 18-ohm cable.

- Cable 2 comprises two flat strip conductors separated by very thin insulation and has Zo between 8 and 20 ohms, Fig 4. The response is shown in trace 2, Fig 3.

Fig 4. Isolda cable.

- Figure-of-eight, or zip cables, have Zo between 90 ohms and 200 ohms, Fig 5, with response as in trace 3 in Fig 3.

Fig 5. Figure-of-eight or zip cord.

- Cables with two flat strips side-by-side, or two arrays of parallel conductors side-by-side, have Zo between 200 ohms and 700 ohms, giving the response shown in trace 4, Fig 3.

Fig 6. Two flat strips or two parallel bundles.

- Cables with circular cross-section conductors, separated by between 10 mm and 15 mm, Fig 7, have Zo between 150 and 350 ohms with response shown in trace 5, Fig 3.

Fig 7. Two closely-spaced round conductors.

- Cables with round conductors very widely spaced at between 20 mm and 50 mm, have Zo between 300 ohms and 500 ohms, Fig 8, giving a response shown in trace 6, Fig 3.

Fig 8. Round conductors very widely spaced.

- Cables with two conductors, either round or strip, arranged completely separately from each other have Zo between 800 ohms and 1,300 ohms, Fig 9, with response as in trace 7, Fig 3.

Fig 9. Two separate round or flat conductors.

To illustrate how variations in Zo affect the sound, a comparison was made between two identical conductor pairs, where the only difference was the geometry. The first cable, Isolda, comprised two parallel, closely spaced copper strips, 20 mm wide by 0.3 mm thick, separated by 0.1 mm of polyester insulation. This cable has a characteristic impedance, Zo, of 18 ohms. It has very high capacitance and very low inductance (0.01uF, 6.6uH). Fig 10.

Fig 10. Two flat strips close together, “Isolda.”

The second cable comprised two identical Isolda cable strips as above, but in this instance, they were separated by about 300 mm to 500 mm, in two entirely separate bundles, Fig 10. The response of this arrangement, which has very low capacitance and very high inductance (0.000028uF, 49.0uH), is shown in trace 7 in Fig 3, where, Zo is 1,300 ohms.

Fig 10. Two flat strips wide apart.

The different responses of these two cables are shown in traces 2 and 7 in Fig 3. It is important to note that the ONLY difference between two cables is the geometry of the two conductors comprising the cables.

To listen to the difference, click here:

In time order, the white noise samples are: short circuit, resistor equal to one conductor, Isolda, trace 2, Fig 3 and separated strips trace 7. Then music with the same sequence.

Notice how the first three samples, short circuit, resistor and two flat strips, Isolda, Zo 18 ohms, have the same musical balance, whereas the two conductors widely separated, Zo 1,300 ohms, sound bright and edgy, due to the extreme rise in the error at high frequencies.

The longer a high-impedance cable, the greater is the error at high frequencies. The responses of 3.5 m and 7 m lengths of cable 6 are shown in the two traces in Fig 11. The longer the cable, the greater the error.

Fig 11. Response of cables 3.7 m and 7 m long with very wide spaced conductors, Zo 350 ohms.

- WHAT CAUSES THE ERROR?

Transmission line theory states that if the load impedance is much lower than the cable impedance, there will be multiple reflections. See chapter 14, page 483 of:

https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/assets/pdf/alternating-current.pdf

The conclusion is that a transmission line’s characteristic impedance (Z0) increases as the conductor spacing increases. If the conductors are moved away from each other, the distributed capacitance will decrease (greater spacing between capacitor “plates”), and the distributed inductance will increase (less cancellation of the two opposing magnetic fields). Less parallel capacitance and more series inductance result in a smaller current drawn by the line for any given amount of applied voltage, which is a higher impedance. Conversely, bringing the two conductors closer together increases the parallel capacitance and decreases the series inductance. Both changes result in a larger current drawn for a given applied voltage, equating to a lesser impedance.

Further, any two conductors in space form a transmission line – even two bits of wet string – and transmission line effects extend down to DC.

- SIMULATIONS

If there is a close match between the impedance of the cable and the speaker, there will be very few or no reflections. If there is a mismatch, there will be multiple reflections on every musical transient. Fig 12 shows a simulation of cables 2 and 6 in Fig 3 for the simplest transient, a step.

Fig 12. Simulation, step into load matched and load mismatched.

Computer simulation, using National Multisim 13 software, shows that there are 1,000 or more reflections triggered by the transient when there is an impedance mismatch. (similar results are observed with other software, for example, SPICE).

For cable 6, Fig 3, with Zo 476 ohms, driving the dummy speaker load with a step input from a square wave (the simplest transient) gives rise to severe ringing that has many oscillations. This is due to the transient reaching the mis-matched speaker load where only a small fraction of the signal is absorbed by the load. The remainder of the signal is reflected back to the source (the amplifier) where it is reflected back to the load. Again, only a small fraction of the now-diminished signal is absorbed by the speaker, with the remainder reflecting back to the source and so on. Over time, all the reflections will eventually be absorbed in the load.

Compare that with the high capacitance, low inductance cable (Isolda), where there are no reflections.

It is the multiple reflections generated on every transient because of the impedance mismatch that give rise to the error, which appears as an analogue treble roll-off. The higher the characteristic impedance, the greater is the roll-off; the longer the cable, the greater is the roll-off. Double the length, double the roll-off, as shown in Fig 11, for two lengths of cable 6.

- OSCILLOSCOPE MEASUREMENTS

To verify the results of the simulations, a square wave was fed into cable 3, Zo 330 ohms, and the traces shown in Fig 13 were obtained. The left-hand trace is with a mis-matched load of 10 ohms, where ringing is clearly visible. This is similar to the ringing predicted by the simulations. For the right-hand trace, where the load resistance matches the characteristic impedance of the cable, the square wave is nearly perfect with no ringing, again as predicted.

Fig 13. Cable 6, Zo 324 ohms into 10 ohms (left) and 330 ohms (right).

In the next case, Fig 14 the cable is Isolda, Zo 18 ohms, driving the 10-ohm load.

Fig 14. Cable 2, Isolda, Zo 18 ohms, driving a 10-ohm load.

In this case, there are no reflections and the signal in the load (speaker) is the same as at the amplifier terminals.

With a matched cable and load, the signal is completely absorbed by the load with no reflections. With a mis-matched load, there are continuous, multiple reflections triggered by every change in the music, and it takes time for each transient to be completely absorbed by the load. It is the delayed nature of the absorption of the multiple reflections that gives rise to the high frequency roll-off, clearly shown in Fig 3.

Ironically, the mismatched cables do not sound dull, as one would expect because of the roll-off, but they sound bright. This is due to the time-smear caused by the delayed energy release from the multiple reflections. Note that every transient should be one single event, not thousands and thousands of events as it is with every music transient when using mis-matched cables. Note that the effect of the reflections may be measured down to 400 Hz with a high-impedance cable as is clearly shown in Fig 3. With impedance-matched cables this does not occur; one transient is transmitted as just one transient.

An analogy is to imagine steady waves from the open ocean arriving at a gently sloping shore where all the energy is dissipated in the white water as heat and sound and there is no back wash or reflected wave. The shore break is effectively impedance-matched to the waves and there is no reflection. The waves just off the shore are the same as the waves further out, as shown in the left-hand picture, Fig 15.

Contrast this with sea waves hitting a solid wall where little energy is dissipated, resulting in the back wave reflecting off the wall. These waves interact with the oncoming waves, and the resultant sea is chaotic, as shown in the right-hand picture in Fig 15. This is analogous to the chaos in speaker cables where there is a mismatch between the cable and the speaker. This chaos is the main reason for the all-so-common brightness and hardness heard in audio systems.

Fig 15. Waves breaking on gently sloped shore (left) opposed to hitting a sea wall (right).

Many hi-fi companies release demonstration tracks which, more-often-than-not, are very simple in structure, such as a guitar and vocal, lone simple piano or simple percussion. This is because the extra brightness, caused by mis-matched cables, may fool the naive listener into believing there is extra clarity since the reflections do not blur the music. However, if complex music is played, such as Mahler’s symphony No. 2, the result is inevitably a disaster.

Since almost all systems use mis-matched cables, they will never sound as clear as a system using impedance-matched cables. Staff at Townshend Audio have known this since 1978 when they introduced the first Isolda cable comprising six 50-ohm coax cables connected in parallel to give a characteristic impedance of 8.2 ohms. Many customers said that once they had experienced the improvement wrought by impedance matching, it was very hard to go back.

Note that there is traditionally a reluctance to use high-capacitance cables because, in a simple RC (resistor-capacitor) circuit, a high capacitance load will cause a roll-off of high frequencies, but this investigation has found the exact opposite.

Note also that many amplifier designers omit the mandatory 3 microhenry (3 µH) inductor at the output of their Class AB amplifier and rely on the inductance of 3.5 µH or more of widely spaced cable conductors to stabilise the amplifier. It is common knowledge that this is a cynical ploy to force the customer to purchase their own highly inductive cables. The approach at Townshend Audio is to place a 1.5 µH inductor in each leg at the amplifier end of all Isolda cables. This has successfully countered these design faults.

The results of these measurements, both by scientific measurement and by listening tests, would appear to demonstrate conclusively why the various designs of speaker cables sound different from each other. They have also shown that, for a cable to make no difference to the audio signal leaving the amplifier, its characteristic impedance must closely match the impedance of the speaker it is driving.

Details of the test equipment and methods used here have been provided in Appendix A.

- CONCLUSIONS

This detailed investigation into why speaker cables affect the sound of a high-quality audio system in different ways has reached the following conclusions.

1 The property that most affects a cable’s performance is its characteristic impedance (Z0), (see definition in Appendix C) which is determined by its physical construction.

The characteristic impedance (Z0) increases as the conductor spacing increases. If the conductors are moved away from each other, the distributed capacitance will decrease (greater spacing between capacitor “plates”), and the distributed inductance will increase (less cancellation of the two opposing magnetic fields).

Less parallel capacitance and more series inductance results in a smaller current drawn by the line for any given amount of applied voltage, which is a higher impedance. Conversely, bringing the two conductors closer together increases the parallel capacitance and decreases the series inductance. Both changes result in a larger current drawn for a given applied voltage, equating to a lesser impedance.

2 The speaker cable acts as a transmission line (see definition in Appendix C) which, if not terminated by a load (in this case the speaker) with the same impedance as the characteristic impedance (Z0) of the cable itself, will cause a series of reflections, which have an audibly deleterious effect on the transmitted sound signal.

3 The following notes should be observed:

- With a matched cable, the response does not change with length, so un-equal lengths of speaker cable may be used with no change in the sound.

- With a mis-matched cable, having Zo greater than 30 ohms, the longer the cable, the higher is the error and to get a balanced sound between channels, the cables must be of equal length, left and right.

- The impedance match does not have to be exact to get very good results. Below 20 ohms is fine.

- With a mismatch, of maximum 2 to 1, the performance changes little.

- Commonly found mismatches of around 20 to 60 times deliver a compromised sound, which is often bright, edgy and lacking fine detail.

- The use of high-resistance wire and very lossy insulation may tame the brightness, but the system will never sound good because the sound is still riddled with reflections.

- The error increases with longer cables. Typical professional speaker cables that have about 10 mm spacing, resulting in an impedance of around 300 ohms.

- If the cable is matched to the load, the source impedance is not relevant, as there will be no reflections.

- The output (source) impedance of the power amplifier should be as low as possible, for maximum power transfer to the speaker, as any source resistance will waste power. This is for one-way power transfer, source to load, known as simplex transmission. Do not confuse this with duplex transmission, where signals travel in both directions. Here the source, cable and load impedance must all be the same [as in the case of an] (ancient telephone).

- For low-level interconnect signal transmission, typical cables have an impedance of between 50 and 100 ohms and drive a 10 kilohm to 20 kilohm load. There are reflections from the load, but the source resistance is typically the same as the cable impedance, so the reflections will be absorbed in the source resistance and there will be no further reflections. This is known as “back matching” and usually occurs by default in audio and is de rigueur in video.

- There is no frequency component in the basic formula for the impedance of a cable, just the geometry.

- High DC resistance results in poor bass performance.

- A high-loss dielectric distorts the electric field which has a second-order effect on the sound. The best practical insulators are air, PTFE and polyester. The worst is PVC.

- Copper purity, cryogenic and [our proprietary] Fractal™ treatments improve the sound markedly.

- All cables have a unique inductance, capacitance and resistance, regardless of how many strands of conductors make up the cable or how fancy is the weave.

- For widely-spaced cables, changing the spacing or coiling, alters the capacitance and inductance, which alters the characteristic impedance and hence the sound.

- For closely-spaced cables, there is little or no interaction between adjacent cables or conductive objects.

- For mis-matched cables, the longer the run, the more blurred, brash and brighter is the sound. For matched cables, the sound does not change with length, just a minute drop in the volume of sound due to resistance loss, for very long lengths.

- Townshend Audio Isolda and F1 Isolda have similar geometry and both have Zo of 18 ohms, which is typical of the impedance of most speakers above 1 kHz, where it matters most.

Researchers at Townshend Audio have known since the late 1970s that the characteristic impedance, Zo is the “elephant-in-the-room” that defines the basic difference in the sounds produced by different speaker cables. If one really wants high fidelity, ignore this at one’s peril. Cable mismatch is one reason why listeners cannot tell the difference between CD and high-resolution music. The other major reason is that external vibration is blurring the sound. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dW9-r83IvhI&feature=emb_logo

One astute audiophile remarked that utilising the Isolda speaker cable “ended his Alice-in-Wonderland experience with high-end cables” and he is now able to sit down, relax and listen to music.

These measurements and results are expected to be controversial, but critics are invited to duplicate the tests themselves before rushing to judgement.

APPENDIX A: Test Method

For the signal generation and spectrum analysis, Room Equalizer Wizard (REW https://www.roomeqwizard.com/) software was used.

For the computer to analyser, the Focusrite 2i2 Scarlett Solo USB external sound card, Fig 16, was used, connected to a PC.

Fig 16. Focusrite 2i2 Scarlett Solo audio interface.

The monitor speaker output 1 from the rear of the Focusrite 2i2 was connected to the cable under test. The speaker end of the cable was connected to the dummy load.

Input one was connected to the black/ground/cold end of the cable at the dummy load end. The REW was set to output white noise and the spectrum smoothing was set to 1/6.

To facilitate these connections and to directly compare cables, the Cable Analyser shown in Figs 17 to 19 was constructed.

Fig 17. Cable analyser.

Fig 18. Basic circuit of the tester.

Fig 19. Complete tester circuit.

Cables 1 and 2 are connected in parallel for convenience.

The amplifiers are included to amplify the music and to play the results on the speaker.

The sound on the audio tracks are taken directly from the spectrum analyser output of the Focusrite 2i2.

Alternate Method Using Android Phones

Two Android smart phones with the Audio Tool app (https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.julian.apps.AudioTool&hl=en_GB) installed may be substituted for the Focusrite Scarlett interface, the REW software and the computer. Use one phone as the source, with the signal generator set to white noise, with the headphone output(s) connected to the cable under test. Connect an 8-ohm resistor or speaker to the other end of the cable. Use the second phone and connect the black speaker end connection to the microphone input via a 0.47µf DC blocking capacitor. Set the readout to spectrum analyser. Connections are shown in Fig 20.

Fig 20. Connections for 3.5 mm jack.

The effects of the differing cable geometries using this method are quite clear.

APPENDIX B: Three Methods of Deriving Characteristic Impedance

METHOD 1 – Use a VICI DM4070 LCR meter or similar

- Measure the capacitance [C] of the cable with the cable open circuited.

- Measure the inductance (L) of the cable with the end short circuited.

- With capacitance in microfarads and inductance in microhenries calculate the impedance by this formula Zo = √L/C ohms.

The table below shows the results of measuring various lengths of each test cable. (BTW, the length of the cable is irrelevant for this calculation.)

| Cable | Cable Fig 2 | L µH | L µH/m | C µF | C µF/m | Zo ohms | Length m |

| F1 Isolda | 2 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 0.024 | 0.0034 | 19 | 7 |

| Isolda | 2 | 6.6 | 0.94 | 0.0109 | 0.0015 | 18 | 7 |

| 2 Strips far apart | 7 | 49.0 | 7 | 0.000028 | 0.000004 | 1300 | 7 |

| XXXX | 5 | 14.8 | 2.1 | 0.0002 | 0.000028 | 272 | 7 |

| XXXX | 4 | 14.9 | 2.1 | 0.00024 | 0.00003 | 249 | 8 |

| XXXX | 30.6 | 3.0 | 0.00015 | 0.000015 | 476 | 10 | |

| Jump Leads | 7 | 19.2 | 3.8 | 0.0001 | 0.00002 | 440 | 5 |

| Twin & Earth | 3 | 15.4 | 2.2 | 0.00056 | 0.00008 | 165 | 7 |

| XXXX | 6 | 14.5 | 2.0 | 0.00014 | 0.000023 | 324 | 6 |

| Zip | 3 | 38.2 | 0.95 | 0.00407 | 0.0001 | 96.8 | 40* |

| Polk | 18.8 | 2.35 | 0.014 | 0.00017 | 36.6 | 8 |

METHOD 2 – Calculate the Characteristic Impedance

Formula for calculating Zo

This formula is for zero resistance conductors.

METHOD 3 – Measure the Characteristic Impedance

Fig 21. Measuring Zo.

Connect the cable as shown in the schematic Fig 21. Set a 10 kHz square wave on the oscillator and adjust the potentiometer so that an identical square wave is seen on the oscilloscope at each end of the cable. Disconnect the potentiometer and measure the DC resistance. That is the characteristic impedance, Zo, of the cable. See Fig 13 and Fig 14 above.

Measure your cable and calculate the Zo, then compare it with the cables depicted in Fig 3 to see your cable error.

APPENDIX C: Definitions

Characteristic Impedance

The characteristic impedance is the resistance a cable would exhibit if it were infinite in length. This is entirely different from leakage resistance of the dielectric separating the two conductors, and the metallic resistance of the wires themselves.

- Characteristic impedance is purely a function of the capacitance and inductance distributed along the line’s length and would exist even if the dielectric were perfect (infinite parallel resistance) and the wires superconducting (zero series resistance).

- Characteristic impedance (Z0) increases as the conductor spacing increases. If the conductors are moved away from each other, the distributed capacitance will decrease (greater spacing between capacitor “plates”), and the distributed inductance will increase (less cancellation of the two opposing magnetic fields). Less parallel capacitance and more series inductance results in a smaller current drawn by the line for any given amount of applied voltage, which is a higher impedance.

- Conversely, bringing the two conductors closer together increases the parallel capacitance and decreases the series inductance. Both changes result in a larger current drawn for a given applied voltage, equating to a lesser impedance.

Transmission Line

A transmission line is a pair of parallel conductors exhibiting certain characteristics due to distributed capacitance and inductance along their length.

- When a voltage is suddenly applied to one end of a transmission line, both a voltage “wave” and a current “wave” propagate along the line at almost the speed of light.

- If a DC voltage is applied to one end of an infinitely long transmission line, the line will draw current from the DC source as though it were a constant resistance.

- A reflected wave may become re-reflected off the source end of a transmission line if the source’s internal impedance does not match the line’s characteristic impedance. This re-reflected wave will appear, of course, like another pulse signal transmitted from the source.

Acknowledgments

Jack Dinsdale MA, MSc, sometime engineering professor at Cranfield and Dundee Universities, was co-designer in 1960 of the transformer-less transistor power amplifier, the first of its kind to approach “hi-fi” performance.

Further Reading

Cable Theory for Sceptics, Richard Black:

http://www.townshendaudio.com/PDF/Cable%20theory%20for%20Sceptics.pdf

Impedance Matching, Hervé Delétraz 2nd

darTZeel Audio founder and chairman:

Geneva area, Switzerland

http://www.townshendaudio.com/PDF/Impedance_matching%20deletraz%20paper.pdf

Geometry Matters videos:

Max Townshend

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9HrYAyVItY&t=3s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMgBqpfGQ4A

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Od_iHp9rJj8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lozs7KWlQ7Q&t=143s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMgBqpfGQ4A&t=6s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMgBqpfGQ4A&list=TLPQMTQxMDIwMjDet2PE_boYGQ&index=2

Some Cable Sound Deniers

https://audiofi.net/2019/01/audio-engineer-claims-his-null-tester-settles-the-debate-on-wires/

https://sound-au.com/cable-z.htm

https://www.audiosciencereview.com/forum/index.php?threads/radio-frequency-rf-analysis-of-speaker-cables-reflections.7154/page-2

https://sound-au.com/cable-z.htm

https://www.opusklassiek.nl/audiotechniek/cables.htm

http://www.tonestack.net/articles/speaker-building/speaker-cables-facts-and-myths.html

http://www.roger-russell.com/wire/wire.htm

This article is printed with permission of Townshend Audio.

The “Sound” of Speaker Cables: an Analysis

From time to time Copper offers guest articles from audio manufacturers and others in the industry. These viewpoints are their own and we publish them in the spirit of providing information from various perspectives, and encouraging discussion and even debate.