In Part One, Gayle talked about his formative years in audio and the founding of electrostatic loudspeaker company MartinLogan...and left us with a cliffhanger as all of the company’s CLS loudspeakers began failing in the field. The story continues here.

Gayle Sanders in his native habitat.

Gayle Sanders: It was 2:00 am in the morning. In the darkness, hours before the dawn, I was facing my reality. I had failed. I had tried time and time again to fix the problem with the CLS, where the tension of the diaphragm would change over time and create an unwanted resonance and buzzing. I tried everything from power supply changes, grounding reconfigurations, structural mods, diaphragm conditioning, to even invoking sorcery…to no avail. This buzz on all of our CLS speakers was also growing into a rattle that raised its ugly head on each and every speaker out in the field. And I could not fix it.

I stood in the middle of the MartinLogan production floor, stared out into the space of our production area and began to weep. I thought, when the sun comes up, I have to call it quits, call all of our retailers and let them know I’m out of business and have to shut the doors. All of the years, all of the work, all of the trust…gone.

As I wept, the dark corner of an earlier project sitting against a white pillar caught my eye. What was that? Oh yeah, it’s a transducer I had tried early on in development.

I had abandoned it because it had a flat section on the edge of both sides of the diaphragm. It was not a perfect curvilinear line source (hence the name for the CLS loudspeaker), and because of the flat sections on the sides it had a slight high-frequency beaming off-axis. Barely noticeable, but if you listened carefully as you walked by you could hear a slight increase of high frequencies on axis with those sections – it was like a slight shhhh to SHHHHH as you engaged that specific spot. But I also remembered it as having superb bass.

I had abandoned this design in my perfection-fixated, myopic focus on creating the perfect transducer. (You know, the one that reproduces all frequencies with no crossover in a seamless distribution pattern…) Staring at the transducer now, I thought, “It’s not perfect but what have I got to lose?! Build a pair and test them out!”

I quickly put together a prototype assembly rig and fabricated a pair of the “not quite perfect” transducers. The clock was ticking. The MartinLogan team was coming to work in a few hours… and I had to get this thing right…NOW!

By configuring the central area of the transducer in the signature CLS (curved) format I retained the superb dispersion of the CLS. By then creating asymmetric woofer panels on either side, that tuning rendered a very linear, high-excursion bottom end to a usable 50 Hz with a nice suggestion of deep bass at 35 Hz. Whoa dude! Bottom end! Great dispersion! Yes, there was a slight increase of high-frequency energy at the periphery but it was negligible. What remained was that magnificent transparency that only a completely pure, super-low mass, superbly linear, crossoverless transducer can reveal…pure magic.

CLS electrostatic loudspeaker.

During the design process for the CLS, I was also ultra-fixated on making sure that the shipping box for that transducer could be shipped via UPS. The transducer was big – It was 2 feet wide by 4 feet high and it took a great deal of creative design effort to fit that monster into a box that was UPS-able. It was literally 1/4-inch under the maximum UPS height-girth dimension. But now I knew that work was going to pay off.

The morning came. The sun rose. And as morning light flowed onto our production floor, the entire MartinLogan team focused on building this modified transducer. We set to work 24/7. At our expense we sent replacement transducers to each and every dealer and customer in the field – No questions asked. If you had a problem we sent new transducers for free.

Weeks passed. The phone rang off the hook. Everyone was overjoyed. And a small miracle occurred. All of that suffering, not just mine but of everyone who had suffered along with me, created a community and a comradeship. A deep bond began to form. Together we had made it through a very difficult time and had come out of it successfully.

Those of us at MartinLogan, our retailers and our customers became a passionate community that had prevailed and succeeded together! What a wonderful feeling. I learned a big lesson. Rather than known as that company of broken electrostatic speakers, MartinLogan became known as that company you can trust. A company that loves their customers, admits their mistakes and solves your problems, and man did that pay off in the long run.

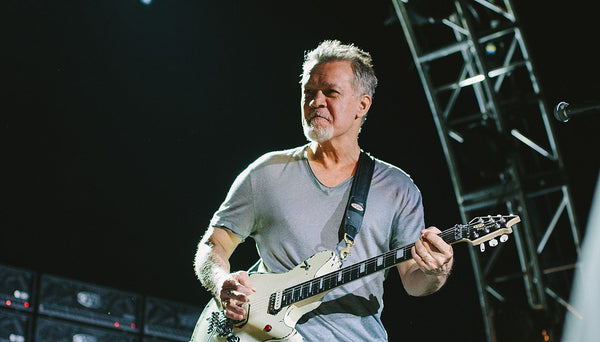

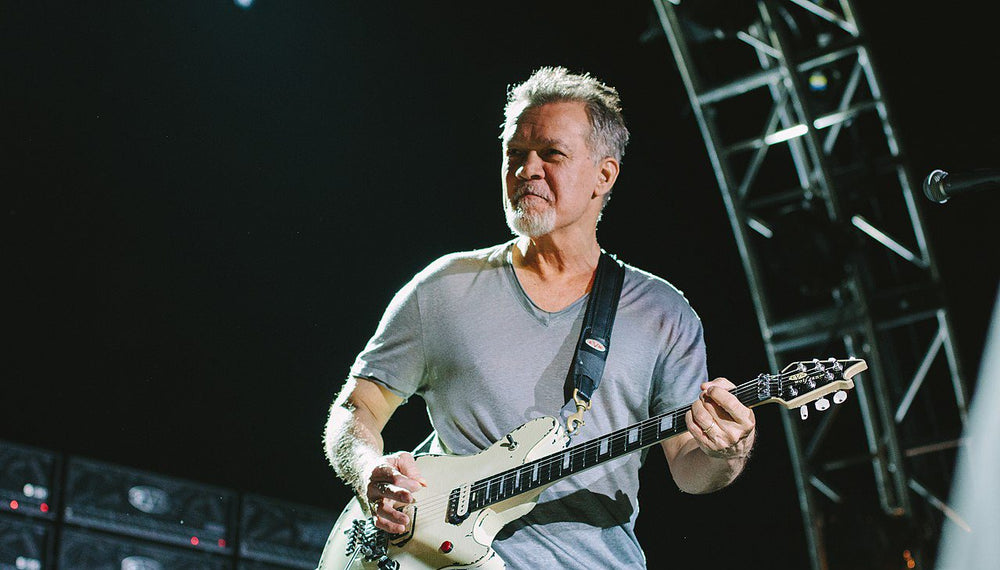

Because sometimes only a Stratocaster will do.

FD: I never knew that. Let’s shift gears completely now! I remember the first time you came out to The Absolute Sound to visit Harry Pearson and myself. Harry kept strong-arming you to have sushi. You’d never had it, were reluctant to try it and he insisted, “you have to get sushi-fied!” Finally we went and you enjoyed it. Actually, we all got sake-fied a little too much and you wound up crashing at Harry’s house. The next morning you’d left, and left a note that said, “I’ve been sushi-fied!” Harry was charmed (and more than a little hung over). What was it like for you to meet Harry that night?

GS: Harry was an icon (no pun intended) in the industry. But to be reviewed by him was a double edged sword! Remember those days Frank? To submit a product to Harry was a bit like heaven and hell…in those days, the high-end audio industry was defined by Harry. To get a rave review would put your company on the map. To get a bad review meant you would then then die on your sword. So, it was with trepidation that I first met Harry.

But that was a great night and it still brings such great memories. From that moment on, I sushi-fied all my friends. As a matter of fact a few years later I ended up in the hinterlands of Japan and as we wandered into a sushi-house we found out we were the first non-Japanese to ever walk through their doors. By the end of the night, they had tried everything on me, and the owner and I were trading songs and singing late into the night.

FD: What made you decide to leave MartinLogan, a company you co-founded?

GS: I thought it was just time to move on. I had spent 30 years in the industry and felt it was time to look at other things in my life. But after a few diversions I realized that audio was my true love. Once it’s in your blood it’s there to stay. And I love it. It’s where I live. It’s what gets me up in the morning…and I found out that I wasn’t done.

In the beginning [right after leaving MartinLogan] I just relaxed. My wife Deborah and I moved to California and just enjoyed life. I supported a few small startups, one of which was in the health food industry. It was great fun but involved even more steps in the market distribution of the products than in the audio industry. As much fun as we had, at the end I decided to sell our company in that there were just too many steps in the distribution chain for anyone to be profitable.

During that time, I was able to look at our industry from a different viewpoint, and could see that the future of how we experience sound was going through a dramatic transformative change. Yes, I think the audiophile world as we know it will still be around for those that love to assemble their own systems and evaluate the sonic changes. In so many ways, I’m that person and I love the process of discovery. And sharing that with other members of our community [is extremely rewarding].

Eikon prototypes.

But the future is changing and the advancing digital technology, as Moore’s Law drives more and more performance, creates new solutions for an engineer’s palette. The convergence of digital advances in DACs, digitally-enabled amps, DSP and on and on, the ability to stream studio-quality music at your fingertips from streaming services like Tidal and Qobuz, along with the Internet of Things – all of this brings powerful tools to advance how we experience high-definition sound in our lives. So I began developing technology to advance our industry into that new and exciting world by integrating those disciplines. This led to the beginning of Eikon Audio and the development of the Image1 system.

[The Eikon Image1 system is comprised of two 4-way active loudspeakers, and the Eikontrol preamplifier with DSP including room correction. – Ed.]

These new digital technologies allowed me to finally explore solutions that weren‘t available in the MartinLogan days. A new world of possibilities was now available. In our loudspeakers I can now throw away the passive crossover components, use dedicated amplification to drive each transducer directly, and tailor the frequency response and time coherence of each driver with surgically precise filters. We can also control the wave front in the time domain. In addition, we can reduce the size of the speaker enclosure to 1/4-normal size yet retain bone-crushing, subterranean bass extension, at incredible sound pressure levels.

Getting there: another Eikon prototype.

We can direct bass energy away from destructive wall reflections and focus it into the room. In addition, with our wavelet technology we can correct room problems dramatically beyond the classic passive and active room treatment schemes.

And that’s just for starters. Not to mention that we can tailor the system to different recording schemes, have control of the system from a phone, and create multi-room whole-house solutions, all without compromising performance.

With this technology Eikon can achieve the precision and resolution of electrostatic loudspeaker panels in a compact system with incredible dynamics and slam. [Because the speakers are able to have a smaller form factor, we can] also begin to really integrate sculpture and art into these incredible feats of engineering.

The hinge didn't make it to final production!

Let’s talk about crossovers. Since the beginning of multiple-driver systems we have used capacitors, resistors, and inductors to filter the audio spectrum, shaping the frequencies that are handled by tweeters, midrange, and woofers. When we use crossovers after the amplifier, it’s a passive crossover. When we use them in front of the amplifier it’s an analog electronic crossover. But no matter what, we have used these crossovers to attenuate high, midrange or lower frequencies, and then try to blend the drivers together in the hopes they can sing together in order to sound as one.

But in designing a loudspeaker, we are trying to create a speaker that delivers as pure a signal as possible, so the ideal situation is to have nothing in the signal path between the amplifier and the driver itself. Putting capacitors, inductors and resistors in the path can only degrade the performance. It’s embarrassing to think that we spend thousands of dollars on cables to connect our amplifier and speakers, and then drive the signal through inductors, resistors and caps. They are rather crude devices at best for shaping the frequency spectrum. And they are even more limiting when we try to adjust performance in the time domain [and have the low, midrange and high-frequencies arrive at our ears at the same time]. That’s why you see designers literally physically positioning the drivers on the baffle board to get them to even come close to some semblance of time alignment. But that just aligns the drivers themselves, not necessarily the complete audio wave launch.

Inductors can suffer from a host of inherent problems ranging from saturation, to hysteresis, to cross-induction. Even the best inductors are problematic. Capacitors are just as problematic. They are inherently storage devices and can easily become nonlinear. They store voltage and then release that energy, and they can suffer from dielectric absorption and hysteresis among other problems – in the best of worlds.

So what is the ideal situation? Purify the signal! Throw away the lossy, destructive passive analog crossover components. Get them out of the signal path and directly connect the amp to each individual driver. Now that we find ourselves in the digital world and have processing power at blazing speeds, the logical place to apply crossover filtering is in the digital domain. Once we impose filters in the digital domain we have supreme control over surgically-precise sonic tailoring. Furthermore, we have control in microseconds over the entire bandwidth of the entire system.

FD: Who did the industrial design? It’s striking. I’m sure you get this a lot, but after seeing pictures of the Eikon I expected the speakers to be bigger.

GS: Thanks Frank – back in the MartinLogan days, elegant design became our identity. We were not only technology-driven but we were also committed to setting standards design-wise. But back then, if you had a beautiful design it almost worked against you. Remember? It had to be ugly to sound good! Hah. But I came from the architectural design world and excellence in design was a significant part of who we were. The same is true with Eikon.

The Image1 is still my work. [The design] was developed over two years, at the same time we were engineering the system, using the classic “old school” design method. Starting with pencil sketches, moving to clay models, working through physical construction…I developed three complete prototypes before the final design. We started with a simple straight-sided enclosure to laminated, curved sides, to the final bevel-cut system you see now. We have a young, talented team supporting my efforts with 3D and advanced virtual reality CAD (computer-aided design) and rendering.

Eikon1 components and models.

And yes, the speakers’ diminutive size is deceiving. By integrating DSP, driver, and cabinet design we are able to dramatically shrink the box size without compromising depth of bass or output.

When designing a traditional passive stand-alone speaker, the engineer is handcuffed by the electro-mechanical alignment requirements of the driver/box relationship. The physics require a very large box to create extended bottom end. If you shrink the box size, the bass will roll off and you are left with vanishing or, at least, anemic bass and extension. This is one of the strengths of our system design orientation. When you integrate every aspect of the system, that is, DSP, amplification, and driver/box design, you have an open palette [that allows you] to shrink the box size and offset that bass rolloff with an equal amount of opposing EQ. It’s not quite that simple but, with the right digital and electro-mechanical engineering and amplification, one can then shrink the box dramatically yet still retain the same bass extension. Very cool.

And so the Image1 is at least half the size of a passive speaker yet has bottom end equal to or beyond in both extension and output, down to 25 Hz.

FD: The “Eikontrol” control unit – how did you come up with that name? – offers user-defined sonic “Personality Maps.” How does that work? It also seems to fly in the face of conventional wisdom, which decrees that there would be only one “accurate” sound for an audio system.

The Eikontrol unit.

GS: One night we were trying to figure out what to call our master control box and Eikontrol just fell out as we were chatting, and you know you have the right name when it keeps being repeated by everyone.

Ah, the Personality Maps…yes there we go again, flying in the face of conventional wisdom. Of course, our goal in creating a reference system is perfection when reproducing the signal, but as you know, that’s far from what happens when you’re in the recording studio. Otherwise we would all be listening to that favorite Stones album when we do a system demo.

How many times [as manufacturers and audiophiles] are we forced to demo with less-than-great music because the great music we really want to listen to has been poorly mixed or EQ’d etc. The Personality Maps allow you to set specific compensation to offset that issue – “opening up” a host of recordings that were almost unlistenable before. I mean. that’s the future of high -performance audio. Not just some narrow version of what to listen to but to open up the palette of opportunity without compromising performance!

So, it’s about accommodating the realities of compromised recordings and broadening the user experience. As a matter of fact, in the future, we intend to publish specific sonic “maps” for our Eikon community for those recordings of great music that are almost unlistenable on conventional reference systems.

Eikon1 system.

FD: Tell us about your in-home demo program. With fewer dealers, this aspect seems more important than it might have been a few years ago. Also, how are you handling it in light of COVID-19, and how has the pandemic affected your company in other ways?

GS: To tell you the truth, it’s been a big challenge for us. Our main launch happened right at the same time COVID-19 hit. Robert Harley had just given the Image1 an extensive review in the April 2020 issue of The Absolute Sound, and we were ready to exhibit at AXPONA (which was canceled). So it’s been an uphill battle. But we have great supporters and our team is growing by leaps and bounds, so we are surviving and even thriving in many ways. “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” We are [getting better] at our unique abilities to create a reference-quality listening experience. And I strongly feel we have superior solutions for the high-end user.

FD: Without spilling any secrets (or spill them here if you want – editors love exclusives), what can we expect to hear from Eikon in the future?

GS: There’s more to come – getting crazy sonic magic out of ever-shrinking boxes. Creating a Master Signature series. We are envisioning new products for the custom-installation world too. That space is also going through dramatic changes and [many] suppliers are locked into the old world, while our technology and design orientation can bring radical new product solutions to that [market] as well.

As they say: “stay tuned!”

Pono digital music player.

Pono digital music player.

Neumann VMS-70 disc cutting lathe at SAE Mastering, Phoenix, Arizona. Courtesy of

Neumann VMS-70 disc cutting lathe at SAE Mastering, Phoenix, Arizona. Courtesy of  VU meters on a Teac A-3340S four-track tape recorder.

VU meters on a Teac A-3340S four-track tape recorder. Vintage Neumann Lathe with a copper DMM blank on the platter. This was not a DMM lathe and was not able to cut copper blanks. This machine predates DMM technology by about 50 years. Image courtesy of

Vintage Neumann Lathe with a copper DMM blank on the platter. This was not a DMM lathe and was not able to cut copper blanks. This machine predates DMM technology by about 50 years. Image courtesy of

The Eikontrol unit.

The Eikontrol unit.

Krell 300i integrated amplifier.

Krell 300i integrated amplifier. Mark Levinson No. 532H amplifier (successor to the No. 532).

Mark Levinson No. 532H amplifier (successor to the No. 532). Krell Illusion II preamplifier and Solo amplifiers.

Krell Illusion II preamplifier and Solo amplifiers. Paul McCartney and friends on the Mark Levinson-sponsored 2005 US tour, Los Angeles STAPLES Center.

Paul McCartney and friends on the Mark Levinson-sponsored 2005 US tour, Los Angeles STAPLES Center.

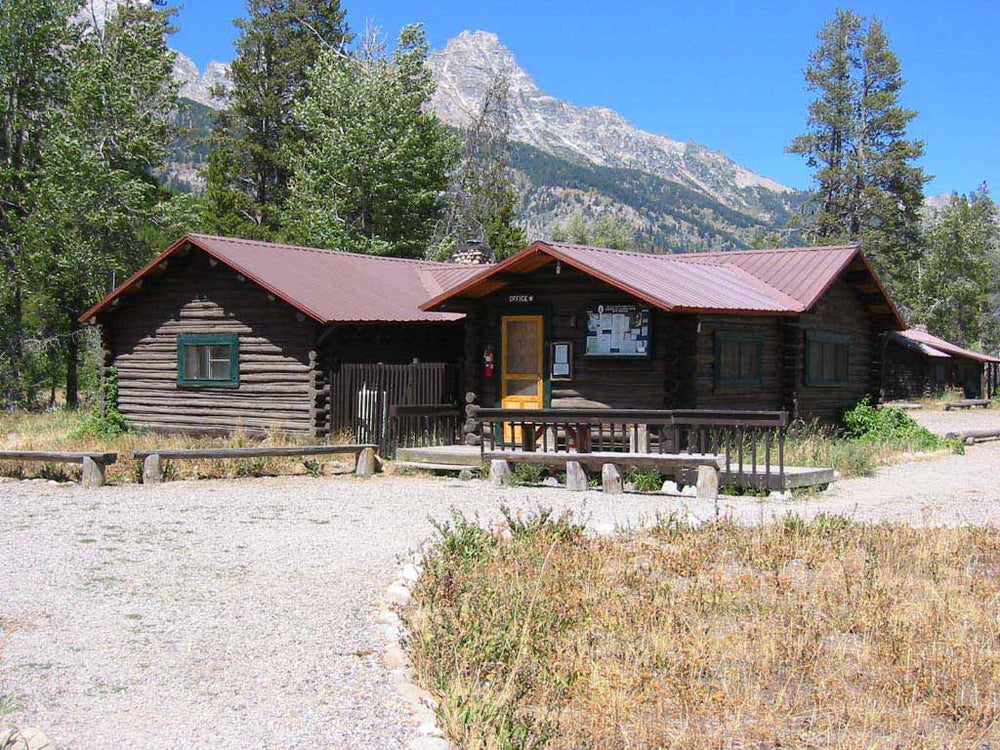

Eaton's Dude Ranch, Wolf, Wyoming. Courtesy of

Eaton's Dude Ranch, Wolf, Wyoming. Courtesy of