In the spring of 2018, an historic event took place in Newark, New Jersey: the Misfits, a local and legendary punk band that disbanded in 1983, reunited for a single area show at the Prudential Center. Nearly 18,000 people travelled from all over to witness founding members Glenn Danzig, Jerry Only, and Doyle Wolfgang von Frankenstein temporarily set aside their differences. The Misfits bridged a gap among fans of metal, horror punk, and hardcore, and we were united again with a blazing set of twenty-seven two- to three-minute songs.

Between tunes, the stage went black, the band yelled out song titles to each other, followed by a count-in, and then the boys from Lodi tore into vintage gems like “Mommy, Can I Go Out & Kill Tonight?,” “Die, Die My Darling,” “Horror Business,” and “Who Killed Marilyn?” It was loud, pure, and fast. Judging by the sold-out venue, punk was alive and well ─ more than I realized.

Also in the attendance was my 40-year-old nephew who came up from Maryland. In 2017, he started Snubbed Records, a label dedicated to punk rock. Who would dare do that in the age of downloads and big corporate media? Well, lots of people. In fact, there are scores of punk-centric labels dotting the landscape. Meet just one of the torch-bearers, Ron Saccoccio.

Tom Methans: I would ask you what the first album you ever purchased was, but since lots of punk kids traded homemade cassettes, what was the first commercial recording you ever bought?

Ron Saccoccio: The first piece of music I ever bought was the Def Leppard Hysteria album on CD, but once I got into punk, it was mostly local bands on tape. I was in fifth or sixth grade. There was a metal chick on my bus, a high schooler. When I was living on an Air Force base my bus stopped at several schools off-base to pick up kids. She had a jean jacket with a Def Leppard patch. I had a crush on her, so I went and bought the CD. It must have been 1988-ish, maybe ’87, which means I was 11 or 12.

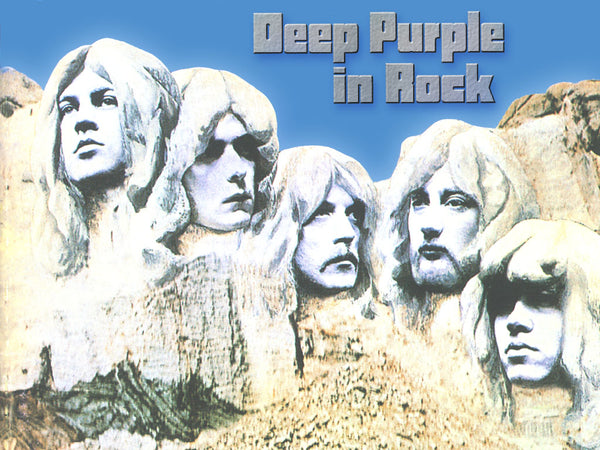

TM: So we were in the same age range when we both got really into music. Although we share an interest in some standard “crossover” punk and rock bands like the Ramones and the Misfits, and maybe Agnostic Front and the Cro-Mags, we are definitely from different musical generations. The first piece of music I bought myself was Queen’s A Night at the Opera back in 1976, followed by lots of mainstream radio-fare. Besides the Sex Pistols, I had no idea there was a full-fledged punk movement, let alone in New York City just a subway ride from my house. How and where did you find your local scene?

RS: That’s cool. I love Queen. In my opinion, Freddie Mercury has the greatest voice in rock n roll. I’m just outside of Annapolis, MD, about 20 minutes from DC and Baltimore. When I was a sophomore in high school I met my best friend Tom. He runs [Snubbed Records] with me today. He was a metal kid, and at the time, I was in this weird Madonna phase. All I listened to was Madonna, seriously. Hanging out with Tom, I started listening to some metal bands and began playing bass guitar. He was friends with some of the punk kids in our high school, and I started hanging out with them.

Tom gave me a tape of a local punk band called Citrus Ego, [who were] the first punk I ever heard. Then he let me borrow his Dead Milkmen CDs, and I totally fell in love. The Dead Milkmen were my gateway drug into punk rock. Around that time, some other people I knew started bands. We had a local fire hall and a church hall in the area where bands would play what seemed like every weekend. Since we were so close to DC and Baltimore, we’d head into one of those cities whenever a more popular band was on tour. I was too young for the DC hardcore scene, but I was a big Minor Threat fan.

TM: You shouldn’t be embarrassed about loving Madonna. Every young boy had a thing for her. My fleeting moment was when she performed “Like a Virgin” in a lingerie wedding dress on the 1984 MTV Video Music Awards.

The DC area was ground zero for some iconic bands, about half of them started by Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, but then you had the Bad Brains, Dag Nasty, and the then up-and-coming Henry Rollins. The Dead Milkmen are out of Philadelphia.

You could draw a line from DC through Philly/Jersey, New York City, and Boston to create a greater East Coast punk region of young people picking up instruments, starting bands, and trading tapes. I grew up on arena rock and so I never really bothered to seek out any of these mostly unknown and unsigned groups. You, on the other hand, created your own label in 2017, Snubbed Records. Who are you, a basic 9-to-5er, to play god?!

RS: Ha ha, yeah, most of the bands I started listening to were unknown [at the time], but I think that’s what drew me to them. Literally, anyone can play bass in a punk band. In 2015, I ran into my friend Shaun who I had played in bands with during my college years. He was in a group, and they were looking for a bass player. I agreed to go to one of their practices and ended up joining. I was shopping our first CD to different indie/punk labels but wasn’t getting any responses, so I decided to start my own label.

Ron and his Fender Precision Bass, playing with the Alements.

To be honest, I started [the label] at first just to be able to say that our band was signed. We were looking to get better shows at some of the larger venues in DC and Baltimore. I found that clubs are way more likely to respond to an e-mail from a record label owner sent on behalf of the band instead of an e-mail from the sh*tty bass player. It worked. We got a gig with Agent Orange at the Rock & Roll Hotel in DC ─ they’ve closed down since then. We even had a green room that night, which was pretty cool, and it was stocked with candy bars, which only I was excited about.

As soon as I founded Snubbed, bands hit me up to join. So, it quickly became a real-ish label.

TM: Agent Orange is big! You were driven to make music, and you just did it without any formal training. Is that DIY part of punk (i.e. “anyone can play bass in a punk band”) what attracted you, or was it a specific performer or sound?

RS: I think what connected me the most was the sense of fitting in. I played sports growing up and into high school, but I didn’t really feel comfortable around the jocks and preppy kids. I got along fine with them, but we just didn’t have anything in common outside of sports. Whenever I’d go to a punk show, I’d feel comfortable, welcome, and I’d always have a good time. I also loved that I could see a favorite band and meet them after they played. When you’d go to a show you were part of the event. That’s still true today. Some of my best friends now are people I’ve met over the last five years playing shows.

TM: You speak to a sense of camaraderie and inclusion not found in classic rock. There are films of old punk shows, and there’s barely a stage sometimes ─ just everyone at the same level. Anyone could help load the band in, watch them, drink beers together after loading out, and perhaps even ride in the drummer’s dad’s van to the next town. It was a little different from vaunted bands like Led Zeppelin. There’s no way Jimmy Page was inviting some random dude back to Aleister Crowley’s house.

Now, you’re building your own community with local acts, bands from the South and California, and even groups from Brazil and Germany. You recently added The Queers and Savage Remains to the label roster. Are you courting bands, or are they coming to you? And part two of this question’: Do you wish you had been doing this your whole life, given the apocalyptic era we’re living in?

RS: I think every band has come to me to tell you the truth. I courted the first band I signed, but they broke up right after releasing their album, which sucks for me. Bands still contact me, but I’m not signing anyone right now since everything has come to a stop. I do wish I started this a lot sooner, like in the ‘90s. Back then, everyone bought music, whether it was tape, vinyl or CD. Now, everyone is streaming, so it’s almost impossible to make money selling music no one has heard of, especially while there are no shows going on.

TM: It is a rough time for everyone in entertainment. My friend in Italy finally started playing gigs again but that’s Italy. Meanwhile, a buddy at Live Nation is still furloughed. It looks like it will be a while until we attend indoor shows. Nevertheless, I see you have branched out into some eye-catching merch and even coffee. How did that come about?

RS: Yeah, everybody thinks the entertainment industry is made up of super-rich artists, but tons of other people depend on live shows, whether it be music or stand-up comedy, to pay their rent.

Just over a year ago, I went to see The Undead. Their guitarist Bobby Steele was the original guitarist for the Misfits. Anyway, they were selling their own [brand of] coffee, and everyone at the show seemed pleasantly surprised to see coffee for sale. I hung out with Bobby that night; he and his wife Diana are both super-friendly people. They gave me the name of the coffee company they went through, Deadly Grounds Coffee from Connecticut. They do horror-themed roasts, pretty cool stuff. I talked to Tom, the owner, and we developed a roast that we call “Punk Roast.” It actually sells better than the music, but we add music to the deal as well ─ you get free downloads when you buy a bag. So many people like coffee, and it’s helping us stay afloat during this period of no shows.

TM: Punk and coffee do seem to go together.

Now, there’s no way we can have a Copper interview unless we discuss your playback equipment.

Just for context, I have a collection of decent mid-priced US-made gear, while some of my colleagues have phono cartridges worth as much as my entire rig! What’s your stereo like?

RS: So this is the point in the interview where I lose all credibility, ha ha! I have a smartphone. The end. Oh, and a $75 record player with a built-in speaker, probably one or two notches better than a Fisher-Price. But my friend and singer in our band, Alex, has a recording studio, and I have access to some really nice equipment when I need to listen for recording purposes. He also records Snubbed bands that are in the Maryland area.

The Lauson CL502 costs more like around $40.

TM: My music biz friends have the sh*ttiest stereo equipment. If your aunt Angie [my wife] gave you a $5,000 check instead of the usual $25 Target gift card, how would you spend it, on stereo equipment or a new bass guitar or amp?

RS: I’d probably use it to go after a well-known punk band, not sure which one exactly, but I’d try to talk them into doing a 7-inch [single] with us so we could get more exposure.

TM: What are your thoughts about high-end audio nerds and all the money we pour into gear just to hear the barely audible parts of a record?

RS: I think it’s cool, I have a friend who’s an audio nerd, he always tries to play me stuff, but my ears are untrained.

TM: If I had 5K, I would buy lots of used records. It would take me years to clean, organize, and listen to them. Maybe I would get a subwoofer. At 54, it’s not like my hearing is getting better after decades of shows, and equipment upgrades aren’t going to change that. All I care about is mood, music, and memory. No special pressing of the Ramones, New York Dolls, or Iggy Pop albums could improve the original groove. In fact, the imperfections make them more perfect. Is it even possible to seize punk’s essence and immediacy on a recording?

RS: This may sound crazy because everyone always tells me it is, but I prefer live recordings/albums. If I listen to the Ramones, it’s almost always either It’s Alive (1979) or Loco Live (1992). One of my favorite record labels, Fat Wreck Chords (they spell it that way, it’s not me trying to be clever), puts out a Live in a Dive album for just about every band on their label. I like hearing the f*ck ups, the banter between songs, and the crowd response. Punk is usually [played] a lot faster live as well, especially The Ramones. It’s impossible to capture the immediacy of it all, but live albums capture enough of the essence of a live show to keep me more entertained than just hearing the song “clean.”

TM: Live in a Dive sounds like the best concept ever! To this day, one of my favorite records of all time is Aerosmith’s Live! Bootleg (1978). It’s gritty and unpolished with imperfections all over the place. Some of it was even transferred from cassettes. Anything done to fix the dirt would destroy the record.

No more softball questions. Now, the lightning round:

TM: How much do you love Diana Krall, come on?

RS: I had to Google her. That should answer that.

TM: Will you press double-length 45 RPM 12-inch vinyl?

RS: No.

TM: How about a 200-gram record?

RS: No.

TM: You gotta give me at least 180 grams.

RS: No.

TM: Any super hi-def limited pressings?

RS: No.

TM: I’m guessing… no SACDs are coming my way?

RS: No…not because I wouldn’t want any of that stuff, but it’s super expensive to have [it] pressed. And it’s super hard to compete with the bigger labels ─ and [when you do things like that] the higher your prices go.

And, I mean, it’s punk rock.

TM: I just couldn’t let the interview end without poking fun at audiophiles.

If you would like to check out some new bands, buy coffee, or grab a cool t-shirt, visit Ron at Snubbed Records.

I cannot give you my opinion on this incredible story. I can’t because the concept of an opinion with regard to this work is trifling. The experience of reading this book changed my playing, my approach to practicing (which I never relished but regarded as necessary drudgery), and yes, this read indeed changed my life. We could talk about all that but who cares, right?

So, let’s talk about the story. Early on Victor talks about a strange man named Michael who shows up unannounced in Victor’s apartment. Not at the door but inside his locked apartment. Michael became a friend, a prophet, and a seer in Victor’s life. On my first read I made a mental note to ask Victor someday whether Michael was real, or a tool Victor was using to get his point across. By the second read I realized that did not matter and I was letting that discussion in my head get in the way of what Victor was trying to show me. If Michael was a literary tool then Wooten is a brilliant writer and teacher in his own right. Wooten was able to separate himself from the Michael character and come across genuinely as confused as the reader. If Michael was real than Victor is one of the luckiest guys on the planet.

One of the most powerful statements comes in the Prelude chapter (sort of a Chapter 2; open the book you’ll see what I mean) that ultimately validates everything that comes after.

“I’m not sure if

I cannot give you my opinion on this incredible story. I can’t because the concept of an opinion with regard to this work is trifling. The experience of reading this book changed my playing, my approach to practicing (which I never relished but regarded as necessary drudgery), and yes, this read indeed changed my life. We could talk about all that but who cares, right?

So, let’s talk about the story. Early on Victor talks about a strange man named Michael who shows up unannounced in Victor’s apartment. Not at the door but inside his locked apartment. Michael became a friend, a prophet, and a seer in Victor’s life. On my first read I made a mental note to ask Victor someday whether Michael was real, or a tool Victor was using to get his point across. By the second read I realized that did not matter and I was letting that discussion in my head get in the way of what Victor was trying to show me. If Michael was a literary tool then Wooten is a brilliant writer and teacher in his own right. Wooten was able to separate himself from the Michael character and come across genuinely as confused as the reader. If Michael was real than Victor is one of the luckiest guys on the planet.

One of the most powerful statements comes in the Prelude chapter (sort of a Chapter 2; open the book you’ll see what I mean) that ultimately validates everything that comes after.

“I’m not sure if  Courtesy of

Courtesy of