Loading...

Issue 110

Changing Perspectives

Getting to the Point

Goin’ to the Bank!

This is a fax I received from Les Paul in 1992. In it he answers a series of questions I’d asked him in researching an article for The Absolute Sound in 1991, including queries about record sales figures, why some recordings didn’t have multi-tracked vocals, his favorite guitar players and more. The last sentence refers to the fact that I was looking for a Scott 22D amplifier (I think it was an amp) for him. I never found one.

If only she’d look at me like that…from Audio, November 1963.

This Empire Grenadier sure looked pretty, and you could serve hors d’oeuvres off the top! From Audio, April 1966.

SEE! HEAR! COMPARE! Now that’s what we call in-store demo. From Audio, but I got lost trying to find the issue this ad appeared in.

This article was first published in Issue 104.

Bassic Necessity

In his Issue 108 column Dan Schwartz related that Paul McGowan had proposed a series on why a bass instrument was necessary. Drums keep the beat and guitars and other instruments carry the melody and harmony, so what is the bass for? I don’t want to steal Dan’s musical thunder but I have a few ideas and examples.

First up probably answers the question definitively but I have to get a full column out of this so you’ll have to bear with me. Click the next link and be transported back to 1970.

That sir was Larry Graham, the father of slap bass, on that very necessary bass track. The track defines the song. Graham developed this style playing in his mother’s band as a kid. She couldn’t afford the drummer and had to let him go. She could afford Larry since she didn’t have to pay him. Young Larry had to make up for the loss in the bottom of the band’s sound with a technique using his thumb to pluck the bottom bass foundation notes and popping the high strings to imitate the snare or kick (bass drum). Not technically “slap” bass yet but the slap bass style morphed from this. It would soon be everywhere in funk, disco and R&B.

Next we have a jazz example. On Miles Davis’s classic “So What” from Kind of Blue, bassist Paul Chambers starts with a riff in D Dorian (crap, just heard folks clicking out) joined lightly by drummer Jimmy Cobb on snare and ride cymbal, and pianist Bill Evans (!!!) doing two chords Em7(add 4) and Dm7(add4). When the horns come in they each take one note of those chords and follow the piano. The cool dig on the phrase is it starts with the first 9 bars using just the rhythm section (bass, drums, piano). Then on bar 10 the horns come in playing the triads with Evans, but drop out on bar 16 to leave just bass, drums and piano again. Nice. This pattern follows anytime the hook is played.

The idea shifts to an Eb Dorian bass line and the chords go up a half step to Fm7(add4) and Ebm7(add4).

And that’s it. The whole song. One of the most recognized tracks on one of the most influential albums in music history. Duane Allman once related he’d gotten serious on guitar after playing Kind of Blue a couple of thousand times over one summer.

The crazed part is, Miles wrote all this stuff for the tracks on the album just hours before the band arrived and didn’t present any charts. He just outlined scales and passages using a modal approach and the guys had to swing it. Of course, the “guys” were Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb, with pianist Wynton Kelly subbing for Evans on “Freddie Freeloader.” And uh Miles Davis. As far as pure talent, remember there are no frets on that monster Chambers is playing.

Note that when the soloing starts the bass shifts to a walking style and everything swirls around that. No drums or guitars can make a piece swing like that. I’ve heard piano players approach it but even the great Oscar Peterson always had a bassist in his trios.

Also influential were Charles Mingus and Willie Dixon, whose songwriting stood them apart. Then we have the studio cats like James Jamerson with the Motown Funk Brothers and Carol Kaye with the Wrecking Crew out in LA. You would be shocked to know how many hit songs Jamerson and Kaye were instrumental on. For instance, Kaye was in an early session with Sonny and Cher and they showed her the original part for “The Beat Goes On.” She thought it was pretty dull, so she wrote the now famous beginning hook. Major hit.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s Muddy Waters recorded with a few blues trios that along with developments in musical instrument amplifier technology (amplifiers were becoming bigger, louder and more powerful) spawned rock trios of either drums, bass and guitar or drums, bass and keys.

In 1964 Frank Zappa played in a trio, the Muthers, with Paul Woods on bass and Les Papp on drums. In 1966 the prototype for rock power trios called themselves Cream. Suddenly power trios were everywhere. The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Blue Cheer, Grand Funk Railroad and the James Gang with Joe Walsh. Even Led Zeppelin and the Who were essentially power trios with effeminate lead singers.

Yeah I said it.

The trend continued through the 1970s and beyond. Prog rockers like Rush and Triumph. Out of Texas came ZZ Top and Stevie Ray Vaughn and Double Trouble. Emerson, Lake and Palmer, the Goo Goo Dolls, Primus, Nirvana, Motörhead. Green Day, Robin Trower, the Stray Cats, early Genesis, early Bela Fleck and the Flecktones and the Reverend Horton Heat. The list is actually pretty eye-opening and the whole power trio genre cannot be done without the bass guitar.

Oooh. Speaking of the Reverend Jim Heath. The great tradition of double bass in rockabilly presented by Jimbo.

Of course the music industry would buy if it sold but the club managers at the bottom of the food chain were troglodytes. Look it up; it’s a fact. The last band I was in, the Uh-Oh Squad, was a power trio doing New Wave but we couldn’t get work no matter how well we presented the material. The audiences thought we were spot on but club managers kept telling us a trio could never do rock. “You need a second guitarist.” That sent us into dizzying swirls of profanity-laden apoplexy given the mind boggling list of evidence to the contrary. Eventually we had to give in and added a guitar. Luckily Chris “Guitar” Kane was really good.

The Uh-Oh Squad did some great New Wave covers but we especially loved the Police. I was thrilled because the songs were written by the bass player and therefore so much fun to play. Here’s the one that got me the job as vocalist and bassist with the Squad. The band had come to me with different recordings and this one tripped me trig.

I have no idea why Sting was playing a six string instead of a bass through the entire vid. Gotta be a story there. Like a roadie who subsequently disappeared left the bass at the flat, or something like that.

Now for the final word. Jazz fusion brought new styles to bass playing with the likes of Stanley Clarke, Victor Wooten, Michael Manring and Marcus Miller. And you cannot discuss the genre without mentioning the most influential of them all, Jaco Pastorius. His style was mind-blowing and not because of technical prowess or speed. None of us had ever heard a bass played like that before. His approach included melodies reminiscent of synth lines, artificial harmonics (where he would pluck the strings to make them ring out at higher tones than fingered) and strong arm runs that swung. He took the instrument to new levels of playing as a lead instrument and used its percussive capability to crisp advantage.

Here is Jaco live with a song he wrote for his first album with Weather Report.

Now bass players do have a bad rep. The jokes are endless, like:

“What do you call a bass player without a girlfriend?”

“Homeless.”

That one is definitely not true. Since everyone wanted to play guitar there were 100 of those fothermuckers to every one of us. I never had to worry about getting work.

For balance here is a guitarist joke.

“How do you get a guitar player to turn his volume down?”

“Put a chart in front of him.”

OK that one actually is true.

A shout out here to Paul McCartney. The Silver Beatles early on had an art student bassist named Stu Sutcliffe. John, Paul and George shared guitar duties. Sutcliffe quit the band to go back to art school. There was no way George or John would give up the chick magnet guitars (besides they could barely play them…yeah, I said it) so Paul picked up the bass. And props to Paul, and this sometimes gets lost in the light of his songwriting; McCartney became a helluva bass player who created some iconic bass lines throughout the Beatles catalogue.

So Paul McC. I hope I’ve given you something to chew on and shine a light on how crucial the bass is to many genres including jazz, rock, rockabilly, funk, R&B and blues.

Thank you my friend for bringing this topic up. I will get some mileage out of this!

Header image courtesy of Kelly Darwin/Pixabay.

Vinyl and Absolute Polarity: A Technical Exposition

One might think that the whole issue of absolute polarity for vinyl records, a medium essentially invented around 130 years ago, would have been adequately discussed and standardized by now, leaving no room for further debates. For those who may be unaware, absolute polarity, means that a positive going audio signal should result in the speaker moving forward and a negative going signal should move the speaker backward. Since some audio waveforms are assymetrical – the positive half isn’t the same as the negative half – this matters, and the effect is usually audible, unless masked by phase errors or other distortions of the equipment involved, the weakest links usually being the loudspeakers and the listening room acoustics.

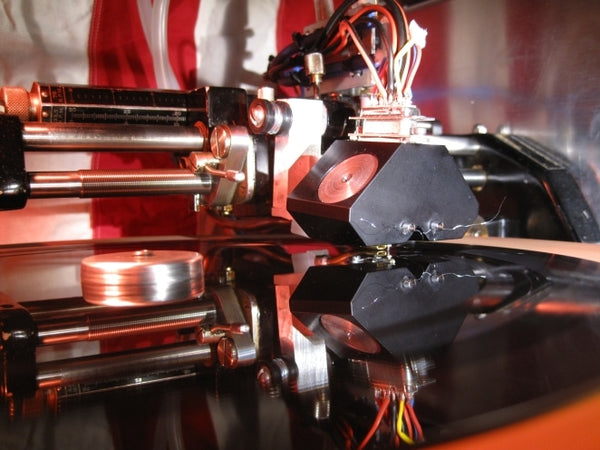

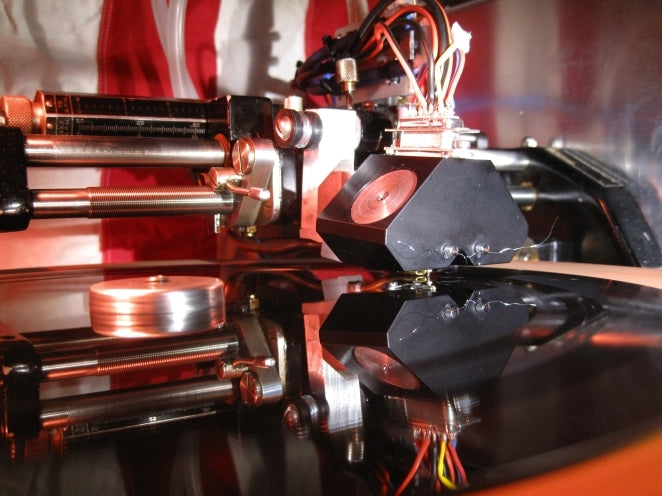

I recently happened upon a proposed method of testing a disk reproduction system (aka, vinyl record reproduction system) for absolute polarity, by dropping the stylus onto a stationary record while recording the output of the system on a digital audio workstation (DAW) and observing the polarity of the impulse on the displayed waveform [1]. A long discussion ensued on which channel is meant to produce a positive output and which one is meant to be negative, with no standards being mentioned.

Subsequently, I found a few more discussions of absolute polarity, this time among people who actually cut records [2] [3] [4]. They were wondering if there were any relevant standards, defining the absolute polarity of disk records – but nobody found any!

The Test Record

A couple of years ago a test record became available, which includes a band of a 370 Hz asymmetric square wave with a 3:7 mark-space ratio (aka duty cycle). This is the “FloKaSon Reference Series: Testtone Record Vol.1 FSTD-001 (2016)” [5], available from Vinylike.

I decided to test the record on a variety of systems. To my horror, absolute polarity was all over the place, with several reproduction cartridges I tested also being of incorrect polarity. I even came across an example of a moving magnet cartridge from the expensive range of a reputable manufacturer, which changed polarity when a replacement stylus assembly was fitted! This is because the orientation of the magnet defines the polarity of the generating system, so if they accidentally stick it in there the wrong way around, or as I suspect, have no clearly defined orientation at the assembly line, there will be no consistent polarity among cartridges or stylus assemblies.

But which ones are correct?

I inspected the record under the microscope, to visually verify its polarity. The grooves of disk records are visible (unlike, say, tape magnetization), making life much easier for the inquisitive soul. I was expecting that the 30 percent pulses of the asymmetric test signalwould be positive-going, but…they simply weren’t! The 70 percent pulses are positive-going on this test record! The cutting system was probably inverting polarity somewhere. The test record is still of course perfectly usable for verifying the absolute polarity of your reproduction system, as long as you keep in mind that the 70 percent shall be “up” (positive) and the 30 percent shall be “down” (negative)! So the question remains: What is the standard?

How do I know that 70 percent is up just by looking at it? This is defined by the standards, of which there are several, but they all fortunately agree on absolute polarity for disk records!

The Standards for Disk Records

AES26-2001 (r2011) [6]

NAB (1964) [7]

DIN 45500 (1975) [8]

IEC 60581 (1978) [9]

IEC 60098 (1987) [10]

RIAA Bulletin E1 (1954) [11]

RIAA Bulletin E2 (1957) [12]

RIAA Bulletin E4 (1961) [13]

RIAA Bulletin E3 (1963) [14]

BS 1928 (1972) [15]

BS 7063 (1989) [16]

JIS S8502 (1973) [17]

JIS C5503 (1979) [18]

JIS S8601 (1981) [19]

These are the latest versions of the standards. Earlier versions of each one exist, and several other standards may also exist, which are either mirror documents of the above, or simply not as comprehensive. The ones included in the list are the ones I have personally found most useful thus far. If you are aware of other standards that contain additional information, please let me know.

The Problems

Part of the problem is that mastering engineers and cartridge manufacturers do not like talking to each other. I have personally tried communicating with several cartridge manufacturers, being a disk mastering engineer myself, regarding compatibility issues, and most of them refused to talk to me. The few who did appeared to have no idea how records are made. Most did not seem interested in changing that fact. I am not only talking about cheap cartridges, by the way. I am also talking about companies claiming to be offering the ultimate cartridge at the price of a luxury car.

Another problem is that none of the standards pertaining to disk records, their manufacturing process, and associated equipment, are actively maintained, betraying a general lack of interest in further technical innovation and standardization in the industry. However, the AES26-2001 (r2011) [6] standard is actively maintained and explicitly covers audio equipment polarity standardization. Fortunately, it includes a section on disk records, specifically covering disk recording and reproducing equipment, monophonic and stereophonic, as well as all other commonly used sound recording and reproducing technologies. It was created by the Audio Engineering Society Standards Committee and was intended to cover the “conservation of the polarity of audio signals,” in accordance with several other standards.

The other standards do not explicitly mention absolute polarity, but they do cover channel phasing and orientation for stereophonic disk records, from which polarity can be inferred. As such, absolute polarity for disk records has been standardized since the very early days of stereophonic records, if not earlier. Its just that it was not explicitly mentioned as absolute polarity. The AES26 standard, first introduced in 1995, simply pointed out the importance of polarity and collected in one document all the relevant information, mostly published elsewhere previously, and presented it in an easy to digest manner. (Other polarity standards exist, but do not cover disk records, so they were not included in the list.)

Absolute polarity is only preserved if it can be maintained throughout the entire process of making a recording and reproducing it. So, it won’t help if your reproduction system is preserving absolute polarity according to the standards, if the record was cut on a disk mastering system that inverted the polarity. Likewise, if the disk mastering system is preserving polarity, but the source, as in the tape machine that was used to reproduce the master tape to provide the signal to be cut, inverted it, the result will still be inverted! Fortunately, all commonly used formats are standardized [6], so it is surprisingly easy to comply with them.

Good Engineering Practice

I believe that all reproduction systems should be verified for absolute polarity, regardless of what “the others” are doing in the recording/mastering chains or consumer equipment. I would also like to see all professional audio facilities make an effort to comply with standards, or at least document what they are doing in terms of how they are configuring their systems.

However, an industry investigation has shown that about 50 percent of all recording and reproducing equipment is inverting polarity, without the user knowing. Given the current chaotic situation, I would advise anyone creating a recording and wishing to have the polarity preserved, to also record 30 seconds of an asymmetric waveform as a “test tone,” regardless of format. Do it on tape, do it on disk, do it on digital. This way, even if you are unsure about your absolute polarity, a knowledgeable engineer can verify the intended polarity and preserve it (or correct it if necessary) through any subsequent process. In my own disk mastering facility, I can invert the polarity of any of the sources if needed, to accommodate recordings that comply as well as those that do not comply with standards. If a suitable asymmetrical signal is provided I can check it with an oscilloscope, or I can just take your word for it if you have verified your system. However, if you are not sure if your recording complies with the standards and have not provided an asymmetric signal, I have no way of knowing for sure what the intended polarity was. In such cases I can only trust my ears.

Needle Drops

This brings us back to the beginning of the article, on the proposed method for verifying the polarity of a disk reproduction system by observing the polarity of the impulse generated by a needle drop. The participants in this discussion did eventually figure out which way it should be, and this method can indeed be useful if a test record is not available. However, the method involves using an A/D converter (ADC) and a digital audio workstation.If you’re going to use this method, have you verified that the ADC and DAW are actually preserving absolute polarity? If not, then you may see an inverted waveform even though your disk reproduction system was actually correctly set up, or vice versa!

Proposed Polarity Verification Method

The most reliable method of verifying absolute polarity on a disk reproduction system is to reproduce a suitable test record of known polarity and observe the output of the preamplifier on an oscilloscope. The test record must of course include a band containing an asymmetric waveform, intended for absolute polarity verification. The correct polarity of the oscilloscope itself can be verified with a simple battery. Some preamplifiers might not be preserving polarity between input and output, in which case you will need to reverse the wiring on your cartridge to compensate. Cartridge wiring color coding is also covered in the standards [10]. In all cases, where the output of your preamplifier appears to be of the wrong polarity, a simple reversal of the + and – wires on both channels of your cartridge will provide instant relief!

Polarity Considerations for Disk Recording Equipment

Those of you who cut records can verify the polarity of your cutting system by cutting a suitable asymmetric waveform and checking it under the microscope, or reproducing the cut on a verified reproduction system. Keep in mind that if both the cutting system and reproduction system are inverting, the polarity will appear to be correct, due to the preservation of the error (by “flipping” the waveform twice) and hence the “relative polarity” . This is not an indication of correct absolute polarity however.

Be careful when trying to cut an asymmetric square wave (or any squarish wave at all), as it contains harmonics extending to very high frequencies. You run a serious risk of frying your cutterhead. You could also cut a half-wave rectified sine wave instead, as recommended by Paul Gold [20] and Peter Butt [21], or an asymmetric sawtooth wave as recommended by Vanderkooy/Lipshitz [22].

The articles by Butt [21] and Vanderkooy/Lipshitz [22] refer to methods of verifying the absolute polarity of magnetic tape recorders (and are in conflict with each other regarding the direction of magnetization), but the same principles and test signals can be applied to disk records.

In any case, proceed with caution. All of the aforementioned waveforms contain a lot of harmonics and will demand considerably more current while cutting a disk, compared to a normal sine wave. If your cutting system is not correctly set up, such signals could excite resonances that cause self-oscillation, which means expensive damage! All such testing shall be done entirely at your own risk. You have been warned!

Some Neumann amplifier racks are known to invert polarity. The FloKaSon Caruso preamplifier is inverting polarity. If the cutting amplifier is also inverting and the head is correctly wired, the result will be correct. The Agnew Analog Reference Instrument Type 891 cutting amplifier [27], which I have developed, preserves polarity, so if used with the Caruso preamplifier and a correctly wired cutterhead, for example, the result would be inverted. To avoid that, you can invert the wiring to the cutterhead (both drive coils and feedback coils on both channels). The result will then be in accordance with the standards. On the other hand, the Agnew Analog Reference Instrument Type 710 disk recording pre-emphasis module preserves polarity as well, so if used with the Type 891 or any other cutting amplifier which preserves polarity, the wiring to the cutterhead shall be configured in the standard manner to preserve polarity on the resulting disk.

If you are monitoring the feedback signal, keep in mind that this is meant to be inverted at some point, relative to the cutting amplifier output signal, it is negative feedback! On the Caruso preamp, the output to the cutting amplifier is inverted relative to the input, and the feedback monitor signal is of opposite polarity to the output. Therefore, the signal at the feedback monitor output should be of the same polarity as the program material input, provided that the cutterhead is correctly wired and labeled. The correct wiring of the cutterhead depends on whether the cutting amplifier is inverting or not.

Each make and model of cutting electronics is designed differently, so you will need to do some figuring out of how the equipment is configured when putting together a disk mastering system.

Also keep in mind that your microscope might be inverting the image it displays and that on most lathes the microscope is located at the opposite side of the disk. You need to imagine how the reproducing cartridge will respond to the groove modulation you are seeing and if you are looking at a (possibly inverted) image from the opposite side to where a tonearm is usually located, thing can get confusing. Once you manage to orient yourself, it should be easy to confirm the polarity visually.

The Definition of Absolute Polarity for Disk Records

According to all the standards, a positive signal voltage applied to both channels of a stereophonic system, or a monophonic system, shall produce an outward lateral motion of the cutting stylus, away from the center of the disk, towards the rim.

Consequently, an outward lateral motion of the reproduction stylus shall produce a positive-going voltage at both channels of a stereophonic reproduction system.

But is absolute polarity audible?

Absolutely [23]. A lot of real-life sounds cause asymmetric variations in air pressure [24] and our hearing mechanism is quite sensitive to this [25]. Other perception mechanisms may also contribute to “hearing” absolute polarity, under certain conditions. As such, there is no question about the importance of preserving absolute polarity in our recordings [26]. The information is easily stored in recorded form, on all media. The audibility upon reproduction will obviously depend on the ability of the reproduction system to preserve and present this information without too much loss. Even for systems that don’t have adequate resolution to enable the listener to clearly perceive the effect of polarity inversion, no harm is done by preserving the correct polarity. On systems where the difference is audible though, an unnecessary deviation from the intended auditory experience would be introduced if absolute polarity has not been maintained.

Conclusion

Admittedly, with the exception of pointing to a suitable, relatively recently-produced test record, and the discussion on some recently introduced equipment for disk recording, most of the information presented in this article is nothing new. Given the circumstances, however, collecting this under one roof, in a publicly accessible article, seemed like a good idea, to help preserve the knowledge and hopefully stimulate renewed interest in the correct application of the technology by manufacturers of records and record manufacturing or reproducing equipment, as well as the correct use of the technology by the discerning listener, to rediscover the true potential of the medium.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sabine Agnew for tirelessly editing my notes into something readable, as well as the engineers and organizations who participated in standardization efforts, passing on to subsequent generations the cultural heritage of a great body of recorded sound in an internationally accepted and standardized format. Special thanks are also due to Flo Kaufmann, of FloKaSon, Switzerland, for the several interesting discussions, for producing the test record and for designing some of the equipment that inspired me to write this article.

References

[1] back2vinyl, “Finally – an absolute polarity test for vinyl playback,” Steve Hoffman Fo-

rum, 2015 (Retrieved on January 10, 2018).http://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/finally-an-absolute-polarity-test-for-vinyl-playback.473528/.

[2] markrob, “Absolute Polarity,” The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls Forum, 2011 (Retrieved on January 10, 2018). https://www.lathetrolls.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=2573.

[3] W. Kirkwood, “Vinyl Polarity Relationships in the Westrex 45/45 Systems,” The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls Forum, 2016 (Retrieved on January 10, 2018). https://www.lathetrolls.com/viewtopic.php?=1&t=6661.

[4] richard ec2, “When cutting a record, which channel has inverted polarity?,” The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls Forum, 2015 (Retrieved on January 10, 2018).https://www.lathetrolls.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=5526.

[5] FloKaSon, “FloKaSon Reference Series: Testtone Record Vol.1 FSTD-001,” 2016.

[6] AES, “AES recommended practice for professional audio – Conservation of the polarity of audio signals (Revision of AES26-1995),” Tech. Rep. AES26-2001(r2011), Audio Engineering Society Inc., May 2011.

[7] NAB, “NAB Audio Recording and Reproducing Standards for Disc Recording and Reproducing,” National Association of Broadcasters, 1964.

[8] DIN, “Hi-fi Technics – Requirements For Disk Record Reproducing Equipments,”Tech. Rep. DIN 45500, Deutsches Institut für Normung, 1975.

[9] IEC, “High fidelity audio equipment and systems: Minimum performance requirements,” Tech. Rep. IEC 60581, International Electrotechnical Commission, Jan. 1978.

[10] IEC, “Analogue audio disk records and reproducing equipment,” Tech. Rep. IEC60098, International Standards Commission, 1987.

[11] RIAA, “Standard Recording and Reproducing Characteristic,” Tech. Rep. RIAA Bulletin E1, Record Industry Association of America Inc., 1954.

[12] RIAA, “Dimensional Standards of Disc Phonograph Records,” Tech. Rep. RIAA Bulletin E2, Record Industry Association of America Inc., 1957.

[13] RIAA, “Standards For Stereophonic Disk Records,” Tech. Rep. RIAA Bulletin E3, Record Industry Association of America Inc., Oct. 1963.

[14] RIAA, “Dimensional Standards: Disc Phonograph Records For Home Use,” Tech. Rep. RIAA Bulletin E4, Record Industry Association of America Inc., Oct. 1963.

[15] BSI, “Specification for processed disk records and reproducing equipments,” Tech. Rep. BS 1928, British Standards Institution, Committee EPL/100, Jan. 1972.

[16] BSI, “Specification for analogue audio disk records and reproducing equipment,” Tech. Rep. BS 7063, British Standards Institution, Committee EPL/100, Feb. 1989.

17] JSA, “Disk Records,” Tech. Rep. JIS S8502, Japanese Standards Association, 1973.

[18] JSA, “Phonograph Pick-Ups,” Tech. Rep. JIS C5503, Japanese Standards Association, 1979.

[19] JSA, “Disk Records,” Tech. Rep. JIS S8601, Japanese Standards Association, Jan. 1981.

[20] P. Gold, “When cutting a record, which channel has inverted polarity?,” The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls Forum, 2015 (Retrieved on January 10, 2018). https://www.lathetrolls.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=5526#p33887.

[21] P. Butt, “A Proposed Method for Uniform Determination of Polarity Response of Magnetic Reproducers,” in Audio Engineering Society Convention 66, May 1980. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=3724.

[22] J. Vanderkooy and S. P. Lipshitz, “Polarity and Phase Standards for Analog Tape Recorders,” in Audio Engineering Society Convention 69, May 1981. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=11959.

[23] S. P. Lipshitz, M. Pocock, and J. Vanderkooy, “On the Audibility of Midrange Phase Distortion in Audio Systems,” J. Audio Eng. Soc, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 580–595, 1982. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=3824.

[24] W. L. Hetrich, “Real-World Audio Wave Form Asymmetries and the Effect on the Audio Chain,” in Audio Engineering Society Convention 55, Oct 1976. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=2221.

[25] M. R. Schroeder, “Models of Hearing,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 63, pp. 1332–1350, Sept 1975.

[26] P. Copeland, “Manual of Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques,” The British Library, pp. 22–23, 2008.

This article was originally published on the Agnew Analog Reference Instruments website, www.agnewanalog.com.

Steely Dan, Redux

Steely Dan has such a smooth sound, it’s easy to imagine them appearing fully-formed from the musical ether. Needless to say, that wasn’t the case. Singer/keyboardist Donald Fagen had met guitarist/bassist Walter Becker in 1967 while they were attending Bard College in the Catskills. They both loved R&B, pop, and jazz, and they both wanted to succeed as songwriters.

Obviously, they needed to be in NYC. By 1968 they’d started pitching songs at the famous Brill Building, where the likes of Burt Bacharach and Carole King tried to interest producers in their wares. Fagen and Becker did get some decent nibbles — they were commissioned to write a movie score, plus Barbra Streisand recorded one of their songs – but this approach was clearly not going to lead to the big time.

So, they struck out on their own, founding Steely Dan in 1972. That same year they signed with ABC Records to produce their first album, Can’t Buy a Thrill. The singles, “Do It Again” and “Reeling in the Years,” are still two of their most recognized songs. Quite a start!

Unique to this album is the presence of David Palmer, who was hired as lead vocalist for a couple of songs. Fagen and Becker originally set up a full band, but it turned out that only the two of them remained constant members of Steely Dan, relying on a big roster of session musicians for everything else. On subsequent albums, Fagen sang all the leads.

“Dirty Work” is one of the Palmer tracks, a laid-back blues rock number which delays the onset of jazz harmonies and textures (including that Hammond organ!) until the second half of the song. It’s strange to hear Palmer’s quivering tenor instead of Fagen’s voice.

The toe-tapping melody is in sharp contrast with the grim contents of the lyrics, and that dichotomy became a common technique in Steely Dan songs. For example, there’s “King of the World, from Countdown to Ecstasy (1973), which deals with surviving a nuclear holocaust in a disturbingly upbeat tone.

This quirky funk track sizzles with Jim Hodder’s tight drumming. Hodder, along with guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, were part of Steely Dan at this point, a rung above the other eight session instrumentalists and six backing vocalists. Fagen lays down a leaping synthesizer solo (starting at 1:54) that puts into music the image of a survivor wandering the scorched, empty land.

It’s not just because of their music and lyrics, or their famously detailed studio work, that Steely Dan is an industry original. Frankly, they handled every aspect of the business oddly. In 1974 they retired from live playing, only three albums into their career. One hopes that pianist Glenn Gould, who had made the same decision in the classical sector back in 1964, applauded their commitment to studio craftsmanship over on-stage showmanship. Pop music consumers certainly seemed to. While Countdown the Ecstasy had produced no hit singles, “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” from Pretzel Logic (1974) was a smash.

For a band whose sound is based in brass licks and synths, it’s rare to find a song led by strummed acoustic guitar. But that’s what you have in “With a Gun,” which teases the country and western genre. The harmonies are wittily cock-eyed, giving a middle finger to the three-chord standard, and making you wait half a verse before landing on the tonic.

Dark humor is a consistent element of style of Fagen/Becker songs, a fact widely on display in the 1975 album Katy Lied. Just consider the song titles: “Bad Sneakers,” “Your Gold Teeth II,” and “Daddy Don’t Live in That New York City No More.”

And then there’s “Doctor Wu,” as tongue-in-cheek as it is jazzy. The lyrics deal with a jilted man telling his shrink about his lost girlfriend, all the while wondering whether the good doctor is also the woman’s new lover. This song also provides endless examples of the so-called “mu-chord” (warning: music theory ahead), a dissonant jazz chord similar to a sus2 (a triad with added second or ninth) but missing the third of the chord. Because of its prevalence on Steely Dan songs, it’s typically associated with them.

The Royal Scam (1976) and Aja (1977) continued the band’s success, with the latter becoming their highest-selling album as well as a critical triumph. Besides singles like “Josie” and “Deacon Blues,” the record includes an interesting character study in “Black Cow.” The title comes from the root beer floats a woman likes. Musically, the song is notable for its use of contrast, both in pitch (high against low) and timbre (twanging against pinging, for example).

In the last of the first round of Steely Dan albums, Gaucho (1980) employed over 40 session musicians. They style has changed, too, to simpler harmonies and a more atmospheric sound. Keith Jarrett’s name appears among the writers for the title track, but only because he sued for plagiarism when he heard it. He claimed they’d lifted a riff from his 1974 album Belonging, and a judge agreed with him.

Tom Scott’s sax provides a distinctive intro to each verse. The way Fagen plays his keyboard in the same rhythm as his singing is one of the unusual features of the song, as is the Mexican-inspired meandering structure of the chorus.

By this point there were legal battles over ownership of some tracks. Becker was having drug problems and got hit by a car. Things fell apart: Steely Dan broke up in 1981. Happily, that was not a permanent decision. They reunited in 1993 and began a heavy touring schedule to gain back lost ground.

After 20 years of studio silence, they released their eighth studio album in 2000. Not only did Two Against Nature chart well, but it won four Grammy awards, including Album of the Year and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group (for “Cousin Dupree”).

The title track features that signature attention to detail: Daniel Sadownick’s bongos share percussive duties with David Tofani’s sax.

The last album (so far – you never know with Steely Dan) is 2003’s Everything Must Go. There’s some dark stuff on here. “Godwhacker” was inspired by the death of Fagen’s mother from Alzheimer’s. Harking back to the more general apocalyptic humor you can trace all the way through their career, “The Last Mall” announces a shopping center’s final sale, and they do mean final.

Fifteen years and counting without an album, but the band continues. Even after Becker’s 2017 death, Fagen still tours as Steely Dan: These days, that’s him, a bevy of crack session musicians, and the ghost of his musical other half.

This article originally appeared in Issue 77.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Kotivalo.

Binghamton

My first impression of America was Binghamton, New York. With the exception of a few hours’ layover in JFK, (Green Acres was playing on the TV and I seriously considered returning home) this town in western New York was to become my home, not for the three weeks planned, but for the next year. My bride to be, Rita, was waiting at the Greater Binghamton Airport for the delayed arrival of my plane. We had met a few months prior in Scotland where we fell in love and I now I had come to be with her in mid-September 1970.

Our first home was a railroad apartment, shared with two roommates, Miriam and Suzy. To me, starry eyed and besotten, this slum was paradise. The neighborhood consisted of cheap wooden houses with various types of siding. The streets were unkempt and the population looked poor.

The day following my arrival, Rita had to go to school so I explored downtown Binghamton. I found a bar and had my first American beer, Genesee Cream Ale. I recall the name because coming from Scotland where beer has flavor, this beer tasted like watered down cat’s piss. As I wandered the streets that day, I realized that downtown was rundown.

We were evicted from that apartment. Mr. Tesla, our Ukrainian landlord, seemingly disapproved of a man sharing the apartment with his girlfriend (apparently the walls were thin and the sound of our lovemaking distressed him) and he soon gave us our marching orders.

We hired a U-Haul and moved to nearby Conklin Avenue to a house overlooking the Susquehanna River. In contrast to Mr. Tesla, Mrs. Pagano, our new, heavily-accented, Italian landlady, would bring us a tray of home-made lasagna every Sunday afternoon. Sometimes it was ziti but it always tasted the same.

The house had a record player and listening to music was a constant activity. Crosby, Stills and Nash had less than a year prior released their first album. James Taylor had just come out with Sweet Baby James. Elton John’s self-named second album appeared in stores. Judy Collins’ Whales and Nightingales was popular. We played Nashville Skyline from Bob Dylan (remember “Lay Lady Lay?”) I was introduced to Laura Nyro (what a songwriter and that fabulous voice!) and Joni Mitchell. Livingston Taylor, James’s brother, performed at Harpur College and we bought his first album. Two songs come to mind, “Lost in the Love of You” and “Thank You Song.” I also grew fond of Biff Rose, an oddball songwriter/performer whose songs are difficult to describe but one resonates with me, “Just Like a Man,” a poignant, bittersweet lullaby from his first album.

There was music everywhere; and what music. This period, the late sixties, early seventies was, in my opinion, music’s most fertile time since the Great American Songbook era of the 1920 – 1940s. I reveled in it and it became the soundtrack of my new life.

Life in Binghamton was bliss. I was in love, attended classes at Harpur College at SUNY Binghamton and had a locker in the gym. I was, to all intents and purposes a student, albeit unofficially. Security was lax in those days and the guards were probably as stoned as the students. My favorite subjects were “An Appreciation of Classical Music” and a history class with a fabulous professor called Norman Cantor. He was a teacher of medieval history and his eloquent portrayal of those times made the period come alive.

In March of the following year, we traipsed through the snow (Binghamton was in the snow belt) to the courthouse for our wedding. A local judge presided and our two roommates were witnesses. That evening I spent forty of my forty-eight dollars on a lobster dinner to celebrate our marriage which has lasted forty-nine years.

The other day, due to the Coronavirus lockdown we are experiencing as I write, I started to play “Binghamton Music.” I had recently set up one of my best turntables, (the Music Hall MMF9.3 in walnut) and it sounded so good I was inspired to play album after album. Out came Laura and Joni and James and Livingston. But when the needle touched the groove and “Your Song” from Elton John started playing, I was transported back to Conklin Avenue where I sat with my arms around Rita watching the swollen waters of the Susquehanna River flow by.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Andre Carrotflower.

Day After Day…

Day after day, alone (with a lot of media and a great spouse) on a hill…

(What media gets me through these times.)

Here I am, living in Manhattan on the Upper West Side and was just notified that the isolation protocols have been extended to May 15. This morning I also read in a concert industry tip sheet that live concerts will not commence until the fall of 2021. This means that most of my friends are out of work.

There are constant notices seemingly every hour, saying one thing and then another about the length and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is nothing I can do except take it all in…until I just can’t.

It is then that I retreat into my media room and either watch a streaming movie, multi-episodic program or listen to music.

The only conversations that take outside of my apartment are over the phone or via Zoom.

Due to the ubiquitousness of Amazon Prime, Hulu and Netflix, the conversations with friends and relatives eventually get around to what shows we (my wife and I) have watched or are watching.

Nobody asks me what music I’m listening to. That conversation would have worked up to five years ago (maybe). I think that my friends don’t ask me about music because they think it’s like “shop talk” to me.

I have a friend who put up the following very funny announcement on her Facebook page:

“Just Finished Netflix!”

I’m starting to think that many of us may join in that sentiment by the time we can emerge from our cubbyholes.

This is some of what we’ve been streaming:

Unorthodox (four-part miniseries)

The Umbrella Academy (episodic – binged it all)

Curb Your Enthusiasm Season 10

Uncorked (movie)

Shtisel (episodic-binged it all)

Schitt’s Creek (episodic – final season)

Ozark (episodic – binged it all)

The Hunters (binged entire first season)

Bosch (binged Season 6)

The Umbrella Academy. Image courtesy of Netflix.

We also had a Zoom Seder (well-meaning but not very good as it had too many people and lots of technical issues).

Here are some discs we’ve watched:

West Side Story

Guys and Dolls

The Last Waltz (the Band, greatest concert film ever!)

Jaws

Dr. Strangelove

Dr. No

Enter the Dragon

Weekend at Bernie’s

Some Like it Hot

The American Folk Blues Festival Series, Volumes 1 and 2 (essential listening and watching if you love the blues)

For the record (pun intended) these are the artists and the music that I retreat to during angst-driven times.(Nobody has asked about music during our Zoom calls; I think my friends don’t ask me about music because they think it’s like “shop talk” to me. But I think that the readers here will want to know!)

I have thousands of albums and as many artists.

This isn’t the only listening I’ve done since being quarantined but these are the artists that I have been depending on to get me through this particular time:

Howlin’ Wolf, Slim Harpo, Sonny Boy Williamson, T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, Magic Sam, Buddy Guy, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck Group, BB King, Lonnie Johnson, Lightnin’ Hopkins. Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, Curtis Mayfield, Sam Cooke, Albert King, Big Joe Turner, Otis Spann.

Janis Ian, the Beatles, the Cars, the Rolling Stones, Love, the Monkees, Buffalo Springfield, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Bob Dylan, Cream, Paul Simon, Simon and Garfunkel, Bob Marley, The Harder They Come soundtrack, The Band.

1950s Les Paul Juniors and Les Paul Special and a Yamaha THR10 amplifier. Wow!

And finally…well I am a guitar player so I can reach over to a stack of guitars in my home office and plug them in (or not) at any time and play along. I use several of my Gibson Les Paul Juniors and Les Paul Specials (1954. 1956, 1957 and 1958) and my new insanely good (and fun) Yamaha guitar amp, model THR10 (hint: it’s a hell of a lot easier to carry then my old Marshall 100-watt stacks!)

Only 3 lbs., 14″ D x 7″ H x 5.5″ D, 10 watts output, with gain, master, bass, treble, mid, reverb, chorus, flanger, phaser and tremolo controls and a 24-bit D/A converter.

Day after day…

In My Dreams, Redux

Sometime in 1995, Bill Bottrell called and wanted me to be on stand-by. He was supposed to meet someone whom he had been putting off, but just in case, he wanted me to be available to work. Likewise, on the other side of the meeting, he was also being put off.

But it was a happy meeting – Linda Perry proved to be everything that we feared she wasn’t. Love her or hate her, she was a genuine artist. Not that her record company, Interscope, really agreed. She’d had a big hit with “What’s Up”, but according to her, that wasn’t like any of the rest of the album, and it also wasn’t typical of her writing. When her band, 4 Non Blondes, went to make their second album, the label wanted another atypical hit. Under pressure to produce, as the writer, Linda tried to leave the band, but Interscope wanted what they wanted. The band was dropped, but she was held to the deal.

And so they sent her to us, and to Bill. We had apparently gotten a reputation within record companies, based on the Tuesday Night Music Club album, and so they wanted us to manipulate Linda and gradually substitute our music for hers. But after two weeks of working with her, it was obvious to us that their agenda was to be thrown out, and we were going to make the album that Linda wanted.

And the album that Linda wanted was what we made, with early Pink Floyd as an inspiration: it was called In Flight. It was a very happy time for me – my daughter was approaching a year old, and the album was coming out well. I have two main memories of making it, one of which will be obvious, and both involve Grace Slick, the singer from one of my very favorite bands as a young musician. Linda lived in San Francisco at the time, and had become friends with China Kantner. They hatched a plan to have China’s mother, Grace, on the album.

When she showed up, the one track that was more-or-less finished was “In My Dreams”, so that’s what we played for her.

When it was done, the first thing she said was, “Who’s playing bass?” Everyone looked at me. “What did you do to it? I know you did something on the board – I don’t mind that. But what did you do?”

“Nothing,” I said. “It’s just that bass – ” I nodded at my fretless Steinberger L2 – “recorded direct.” She said something like, “That’s amazing.” And all I could think was “This is Jack Casady’s singer saying this…”

Linda had a song called “Knock Me Out” in mind for Grace to sing as a duet, and it became, in my opinion, the centerpiece of the album, with each singer singing their half of a very volatile relationship:

You knocked me out

You bit my lip

You held me down

And kept me sober

Through all this time

With no regret

I guess that’s just the way I liked it

It’s slow, it’s big, it’s stately, it’s got two great singers, and Kevin Gilbert plays truly gnarled licks on Bill’s National with flat-wounds. We play all sorts of rock and roll instruments on the record, but I especially want to mention Kevin’s organ playing (and particularly on the song “In Flight”), which he also played live.

We played live a few times with Linda, and she was as great a person as she was a performer. Our first show was a benefit for APLA, the AIDS Project Los Angeles. My large speaker cabinet was brought in by a crew, but I brought my own amplifier. I put it up on the stage, and jokingly said to her, “Hey Linda, my amp goes up on the cab!” She unquestioningly said, “OK!” and hauled it right up there: the perfect lead singer.

I recall that the first song we did was “Freeway,” which began with a verse solo – and then two things happened: first, drummer Brian MacLeod and I had never been on stage together before this; we had just played in the studio, and we were both kind of shocked by the power of our playing together. It felt like a jet taking off. At the same moment Linda and Kevin played the opening chord of the second verse so hard they that broke strings on both their guitars immediately. I remember a single thought: “This will either crash and burn or fly.” It flew. For the second song, they borrowed guitars from the opening act (Stone Fox, who were on Linda’s label), while the girls in Stone Fox changed their strings.

After the show, a friend told me that it was “like seeing Janis Joplin with Big Brother.” I’ve got a few good memories, but this is among my highest.

This article originally appeared in Issue 18.

Dylan Dials Up JFK, the Wolfman, and Whitman

“Murder Most Foul,” Bob Dylan’s newly released song, is long. It is 17 minutes and change, about as long as “Desolation Row” and “Like a Rolling Stone” combined.

It is Bob’s longest single studio recording, coming in about 23 seconds longer than the entertaining Dylan dream that was “Highlands” from 1999’s Time Out of Mind. I’ll always have a fondness for “Highlands,” for its scene in a coffee shop, where the waitress bets Dylan that he doesn’t read women writers. As a retort, Dylan rhymes “wrong” and “Erica Jong.”

“Murder Most Foul,” released on March 27, 2020, is not a new song or recording, but is said to have been written and recorded around the time of “Tempest,” which would place it in 2012. Dylan’s office, which has always been as accommodating as Bob will allow, could not add anything to the notice on the home page of the official BobDylan.com.

On the right side of the home page is an emblematic photo of President John F. Kennedy, as seen in pride and sorrow as part of the interior decorating scheme of a vast number of American, especially Irish-American, homes, ever since his election, and his death. Inscribed at the bottom of the photo, in a kind of gothic typeface, is the song’s title. On the left, Dylan offers three brief sentences of introduction.

“Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years.

This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.

Stay safe, stay observant, and may God be with you.”

Musically, it is sparse, slow, just a few piano notes and a violin or viola or similar string instrument, with a few faint drum rolls later on. A funeral procession.

The song operates on two parallel themes. Full of rage and anger, the essential theme is the assassination of JFK on November 22, 1963. It is very serious, thrusting in its accusations, skepticism and sarcasm that give life to the only serious conspiracy theory that deserves its oxygen: the notion that Lee Harvey Oswald was not the sole assassin, perhaps not even the assassin. In this theory, Oswald was the “patsy” (or as Dylan free associates, “the Patsy Cline”), the fall guy for a conspiracy of many moving parts, a crazy scheme, really, to kill the president, and which all came together hellaciously well. “They blew off his head while he was still in the car/Shot down like a dog in broad daylight/Twas a matter of timing, and the timing was right.”

The plot, according to the majority of the American public that still believe in the conspiracy, involved so many unsavory members of American institutions—the CIA, the FBI, the Pentagon, the Mafia, a militia of anti-Castro Cuban emigrés, the Teamsters—that the only option has been to cover up the truth for the last 57 years. “What is the truth, where did it go? Ask Oswald and Ruby, they ought to know,” Dylan sings.

Oswald, for those arriving at this movie late, was shot to death at point blank range by small time Dallas strip club owner Jack Ruby on live TV in the middle of Dallas police headquarters while being transferred to another part of the building two days after the assassination. Ruby died of cancer in jail in 1967, insisting until the end that he killed Oswald out of patriotic rage.

The lyrics, as published on bobdylan.com, are in four numbered sections of varying lengths. The first three mix details about the assassination, and the Sixties pop culture explosion that would follow his death, in the form of imagined thoughts and visions of a dying Kennedy. Some are in the form of telephoned requests to disc jockey Wolfman Jack, a New York hustler (real name Bob Smith), who pursued the big bucks through the big beat with a big howl and 250,000 watt (five times the FCC limit for American stations) XERF, its transmitter based in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico, across the Rio Grande from Del Rio in southwest Texas. Wolfman played R&B for teenagers on a signal that could be heard across North America, and on a clear night, around the globe, while also selling mail order products, including live chickens.

Wolfman Jack is introduced as the vehicle for JFK’s life-ebbing hallucinations at the end of the first section: In the last four standalone lines of section one, Dylan calls JFK’s murder the “Greatest magic trick ever under the sun, perfectly executed, skillfully done. Wolfman, oh Wolfman, oh Wolfman howl.” Comparing the assassination to a magic trick may be one reason why, near the end of the song, there is a vision of “Houdini spinning around in his grave”: As if history’s most renowned magician and legendary escape artist never matched the trick Kennedy’s killers pulled off.

Pop culture geeks will be able to get happily lost in the many musical references criss-crossing Kennedy assassination minutiae. Section two introduces the Beatles, name drops Woodstock, Altamont, the Aquarian age, as Kennedy’s limousine races for Parkland Hospital. Section three begins: “Tommy can you hear me, I’m the acid queen…Ridin’ I the back seat, next to my wife/Heading straight on into the afterlife.”

There are images of surgeons trying to save Kennedy’s life, removing his brain, and of the only known real time images of the assassination, known as the Zapruder film. “It’s vile and deceitful–it’s cruel and it’s mean,” Dylan sings, with palpable disgust.

It is a lamentation in the literal sense, an expression of grief, in the Biblical sense. In the Old Testament, the Book of Lamentations is a series of poems or songs of deep sorrow attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, decrying the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE and the beginning the Babylonian exile of the Jewish people. The Book of Lamentations is read, and sung, on the saddest day of the year for observant Jews: Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the month of Av on the Hebrew calendar, which remembers the destruction of both Jewish temples. (Some believe that Jeremiah wrote the Lamentations before the destruction of the first temple, but its destruction was his prophecy.)

The original Lamentations consisted of four chapters, which is perhaps why “Murder Most Foul” has chapters numbered one through four. (A fifth was written later.) The depravity and idol worship, the moral decline of his people that tormented Jeremiah, are echoed by some of what Dylan writes, at the beginning of his chapter four: “What’s New Pussycat…what’d I say/I said the soul of a nation has been torn away/It’s beginning to go down into a slow decay/And that it’s 36 hours past Judgment Day.”

From that point, the rest of chapter four is the longest, at about 80 lines, about three times longer than the other chapters. That also suggests Jeremiah, whose chapters one, two and four contain 22 lines; chapter three, 66 lines. Dylan is not writing with quill and parchment here. Almost all of it seems to be riffing out the rhymes for the sake of rhymes, shouting out song titles, movies, plays, artists. It reminds me of the annual Christmas poem “Greetings, Friends!” in The New Yorker (written for many years by Roger Angell, more recently Ian Frazier), which offers holiday gifts and wishes to friends and the famous using jocular rhymes, such as this one by Frazier from December 23, 2019:

“[For] Michael McFaul, Billie Eilish—

Socks by the carload, highly stylish.”

Dylan implores the Wolfman:

“Play Oscar Peterson and play Stan Getz

Play ‘Blue Sky,’ play Dickie Betts.”

He also sings: “Play Don Henley, play Glenn Frey/’Take it to the Limit’ and let it go by.” Dylan’s invocation of the Eagles could start another conspiracy theory: is it praising, or rhyming lazy? But we don’t want to go there.

Dylan released a second song, “I Contain Multitudes” on April 17. Its title comes from one of Walt Whitman’s, from “Song of Myself, 51”: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well, then I contradict myself/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

He has always embraced his own contradictions, and this rueful song, lightly flavored with pedal steel, Dylan states some of them proudly. “I sing the Songs of Experience, like William Blake/I have no apologies to make.” He acknowledges his dark side, as boastful as any rapper: “I carry four pistols and two sharp knives.” It’s almost like Dylan’s “My Way”; although his singing is understated, the lyrics bite with a rapper’s ferocity. “I’m just like Anne Frank, like Indiana Jones/And them British bad boys the Rolling Stones,” he sings. Come on, Kanye, step up, Drake: This Bob’s for you.

All Dylan lyrics © 2020 by Rider Music.

Whitman, “Song of Myself,” public domain.

“Greetings, Friends!” © The New Yorker magazine.

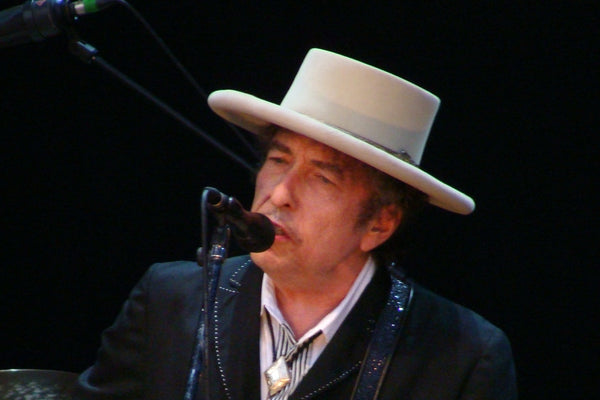

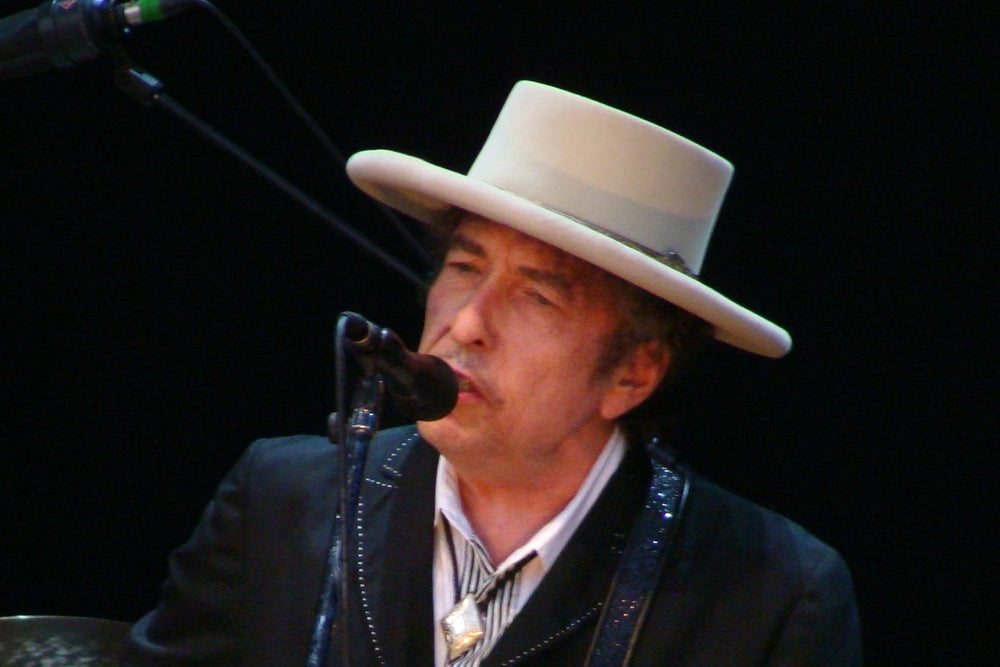

Bob Dylan photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Alberto Cabello.

I Love LA

I sank into the plush soft leather seat and snapped on my seat belt. My surroundings were the inside of the private jet owned by WEA (Warner Music Group, at the time known as Warner-Elektra-Atlantic) We were flying west from New York to Los Angeles. The flight was full, all twelve seats occupied. The other passengers were music business executives and rock stars. I was (maybe) a junior executive, an assistant A&R man for Elektra Records. My boss was Steve Harris, Elektra Records A&R man.

I was heading west to join The New Seekers, a British vocal group formed after the breakup of the original Seekers, doing their first American promotional tour to back up their 1971 single “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing.” That smash hit later became a Coke ad, as those of us as a certain age might remember. In hindsight, I’d say The New Seekers were possibly the inspiration for ABBA. Who came later and were much more successful. ABBA had better songs. Today was a travel day and I’d meet up with them tomorrow.

We landed at Santa Monica Airport and there were a bunch of limos waiting for us. I was ushered into a limo along with Harry Nilsson. The driver asked where we were going and both of us gave our addresses. Knowing my way around LA, I realized that Harry was going to Beverly Hills, and as luck would have it, on the way to Harry’s house we had to pass within half a mile of my apartment, which was located in West Hollywood on San Vicente Blvd.

I said to the driver, “drop me off first,” and Harry says “no, me first.” I said to Harry, “why not drop me off first; it’s just slightly out of the way.”Again, he said no. I didn’t understand, it didn’t seem to make sense, so I asked, “why?” He looks me in the eye and says, “because I’m Harry Nilsson!” And that was that. We were silent for the rest of the ride.

After Harry was dropped off the limo takes me to my apartment. It is just 500 feet down the hill from the Whisky A Go Go which is located on Sunset Blvd.

That night I walk up the hill to the Whiskey. It’s a music biz event for an A&M Records act, Split Enz. They were touring in support of their new hit “I See Red.” Once in the Whiskey I sit with some A&M record company guys and watch the set. About forty-five minutes into the set this drunk behind me starts talking loudly and making noise. I try to ignore him, but he gets louder. Finally, I turn around to shush him and to my surprise, it is Joe Cocker. A very drunk Joe Cocker. He is smiling and trying to stand up and do a toast or something to the boys on stage. Finally, someone next to him quiets him down.

I should mention that Split Enz is a New Zealand rock band fronted by the Finn brothers, Neil, and Tim. Their biggest hit was “I Got You.” A few years later Neil started Crowded House, which Tim later joined; they also had a mega-hit with “Don’t Dream It’s Over.” (Recently Neil joined Fleetwood Mac, replacing the departing Lindsey Buckingham.)

After the set, we all went upstairs to the dressing rooms. There were about forty people milling around and partying. The group included Harry Nilsson, John Lennon, a very pregnant Donna Summer, Bette Midler, and The Exorcist actress Linda Blair. The Finn brothers and band, some of The New Seekers, but no Joe Cocker. I guess Joe couldn’t navigate it up the stairs.

I walk up to Harry and John and say hello. Harry looks at me and says, “you get home OK?” Before I can answer he turns away from me towards John. (Years later I ran into Harry while he was recording Nilsson Schmilsson and he greeted me like an old friend and invited me into the control room to watch and listen to some of that day’s recording session.)

Nilsson Schmilsson master tape.

I walk over to a group standing with Linda Blair. I mention that I understood she came from Connecticut. “Yes, she said, but now I live here in LA.” We chatted for a few minutes, and then I asked her, “how did they spin your head around in The Exorcist? That was amazing!” She looked at me as if I was the stupidest person in the world and hissed at me, “that was a puppet!” Red-faced, I turned away from the group. Truth be known I never did see the movie, but I saw that scene a few times and took it at face value.

Not to be discouraged I walked over to the Finn brothers and Bette Midler. I knew the Finn boys, but not Bette. This time I listened more than I talked. They were telling music biz stories and it was interesting. After a few minutes, Nathan, (Split Enz’s manager) walked over to us. He was looking very annoyed and told the boys that he wanted a band meeting, Now!

Split Enz in all their sartorial splendor.

That left Bette and me standing there, and she said to me, “Oh God, I remember those kinds of meetings.” I knew what she meant. I had read about her first manager and how he yelled and bullied her, basically intimidating her and trying to control her. She was signed to him for a few years till she found lawyers that were able to work out a settlement and break the management contract. “I hear you,” I replied as I knew Nathen was a mean-tempered controlling son of a gun. Bette was fun, unassuming, and very real with no drama. I instantly liked her; I think everyone did.

About forty minutes later the band (Split Enz) came out of the meeting looking a bit drained. Nathan was pissed off that the Finns had changed the setlist and added a new song without checking with him. But even before Split Enz, the brothers had made an impact on the music scene in Australia, having moved there from New Zealand in the mid-1970s. They were successful, eventually becoming one of the biggest groups in Australia. They knew what they wanted to do and had good instincts. Nathan was also Australian and felt easily threatened; he wanted total control of the band’s activities. His alliance with management company Champion Entertainment, run by music biz heavyweight Tommy Mottola gave him influence with the band and that connection helped in getting Split Enz a label deal and their first tour. However, as their careers flourished, especially in the States, Nathan’s grip on them loosened. (Tommy managed Hall and Oates at the time, among others; this is before he became the CEO of Sony Music and married Mariah Carey.)

The next morning, I had to fly to New Orleans with The New Seekers, and Split Enz had to fly up to Seattle. We were all leaving around the same time so Neil asked if I could shepherd both bands to LAX the next day. Sounded like a plan so I had another drink, said good night to everyone and walked down the hill to my apartment.

The morning after, I gathered up The New Seekers and Split Enz, got them checked out of the Continental Hyatt House (known as the Riot House because all the big touring rock bands stayed there and acted like Big Touring Rock Bands; it was a truly wild scene). I loaded them into their cars with me taking the lead car with Neil, Tim, Lyn, and Eve (The New Seekers girls).

We were driving south on Robertson toward the Santa Monica Freeway (I-10 West) when I had stopped at the light at the freeway entrance. I’m looking over my seat speaking with Lyn when I was startled by a pounding on the hood of the car. I face front and it is Bette! She is standing right in the middle of the road. She’s dressed really casual in a peasant blouse and jeans. Her car is stopped at the light alongside us and her driver’s side door wide open. She is smiling and bobbing up and down while pounding on the hood of our car (you cannot make this stuff up). Never mind that she’s stopped her car in the middle of the road with cars all around us. What an amazing coincidence. The traffic light changes to green and Bette jumps back into her car, waves at us again, and drives south on Robertson to go do whatever she was in the middle of doing, while we turn on to I-10W heading for the airport and another rock and roll adventure.

Header image of Los Angeles courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Thomas Pintaric.

Elitism in Audio and Its Implications

Audio and music are passions. They can be a hobby, a vocation, a lifestyle, a love, a way to live or all of these. They are very personal pursuits and as such, there really is no right or wrong in the pursuit, as long as the person is happy doing so – and even at times when they might struggle with their interests.

But when it comes to sharing our passions about audio (and music) on the internet, why is there is so much vitriol and downright meanness in so many posts, reviews and comments? In particular, why do so many think they are elite and that their view is better than the views of others?

I love audio, for itself (the gear and the technology), its results (superior sound quality and easy access to it) and ultimately, for the love of music. As a hobby, which it is for many, it can be very inclusive. There are uncountable enthusiasts who embrace it. Sharing our enthusiasm, insight and knowledge with others can add to our passion and widen the numbers of members in the club. But too often this is not the case.

I have been engaged in audio for a long time, both as a passion and as a profession. I have some industry perspective, as earlier articles in Copper have expressed. Although I have been involved in product marketing and development at the highest levels, I have also built some of my own speakers, which in my early hobbyist days were crudely built and voiced without the benefit of measuring equipment. They probably would not fare well on today’s internet stage, and I am certain these speakers would be panned, my approaches scorned and scolded by “know-betters.” But would these know-it-alls be right? I loved playing my gear and got many hours of enjoyment out of it. Was that wrong? Did I not really enjoy that music?

There are many participants in today’s online dialogues about audio and sound. Some are highly experienced as hobbyists, inventors and tinkerers, and are actual product developers and engineers. The majority of people in and around audio conduct themselves with great respect for the medium and the music. Most are generous about sharing their sonic and musical tastes even if they do not agree with one another. Almost everyone loves to offer advice, insight and views on the best ways to get the most performance and enjoyment out of their components.

But then some others decide that their views are better – and “must” be enforced. While they are few, they are odious as they poison the discussion. It becomes hard to endure the online trolls who think it is their purpose to weigh in on a discussion as if they are the ultimate arbiters of taste and technology. Of course, a lively argument about things we love is common, as in the end we all can have a good listen and perhaps a nice glass of wine. Yet the pervasiveness of online nastiness is more than common enough to have crept into the public dialogue.

We are made the butt of jokes, as what some of us show in this kind of behavior looks mean and irrational. Even the marketing genius Seth Godin has noted such audio behavior as a dysfunction and also warns against scams and ridiculous prices. Godin writes, “If you’re into high-end stereo, it’s far easier to find strident voices in defense of $100,000 stereos than ever before…the true believers are in our faces every day. The problem is that these loud voices may be loud, but they might not be right.”

But in case you think Godin is not an audiophile, consider what he writes about listening to a great system, “…For a minute or two, the drum solo on “Monk’s Dream” is totally and completely alive. It even makes the neighbor’s dog turn his head and stare at the speakers.”

And he is not alone, with many in social media forums decrying demeaning comments, or high-minded but uninformed opinions and bashing of others. Godin’s remarks are is just one example but represent the views of many (he is a keen marketer). Do we really want to be portrayed in this way?

Audio enthusiasts may think of ourselves as in our own club, but we do want more people to join the club, or else without new “members” we might ultimately see the end of the development of new equipment and the achievement of ever better performance. While some large firms still conduct product development for high-performance audio components, they ultimately will not if there is no audience for them. Ask people from smaller companies, and they will tell you how hard and expensive it is to continue to innovate in the field. They also worry about marketing to a greying group to buy and support their efforts.

Have you been to any audio shows? Too many are too filled with grey heads, and the future will need younger people. These new entrants into high-performance audio have interest, but if they are told by some internet expert that their love of streaming, or choice of approach, or the gear they can afford is simply not good or “acceptable,” what motivation do they have to venture further? Without exposure to wonderful experiences like immersive audio and high-quality stereo systems, today’s millennials and GenZs often think and are told that their Bluetooth speakers are “awesome” and unless they experience better how will they know?

Our audio world is composed of many groups. There are the inventors who often lead eponymous firms that realize their ideas. There are the engineers who develop products and technologies using what they have learned or dreamed of and then created to become reality. There are the marketers of corporations that work to discern the unmet needs and open opportunities that lead to innovation. There are the enthusiasts, who help drive innovation by providing valuable feedback and by purchasing products – and participating in online discussions. Added to these groups are all the people who own audio equipment (not just enthusiasts), a very large group indeed as in the US some 98% of households have something that plays music.

All of these groups have opinions and points of view. Sharing them is good and can be interesting and enlightening, but when some have an axe to grind or simply like to sneer at those they consider below them, I maintain that they are toxic, and that this is audio elitism. We should not tolerate it in the audio world, especially if we want to grow our passion and hobby. We can disagree agreeably, and in fact we must. But the kind of negativism that can manifest itself on the internet is more than upsetting; it can be counterproductive.

I ask all who love audio to think hard about this. Discourage the online trolls who make needless and mean commentary. Too many of their unkind remarks, by the way, come from those who often have no real basis to make them, backed up by no facts or technological expertise, with no product comparisons based on experience. But even and maybe especially in light of the fact that elitism in audio is present, we should always strive be kind and welcome all who love music and sound to the party.

Header image courtesy of Pixabay.

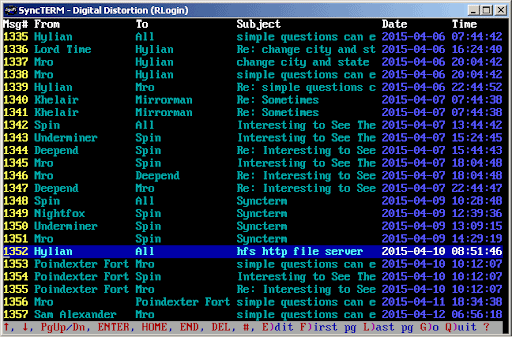

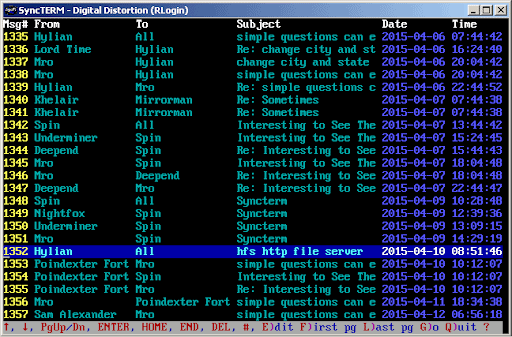

Tales of an Audio Forum Administrator, Part One

Internet forums are a way of life for many of us. We turn to them for information, education, camaraderie, entertainment and friendship. They provide us a place where we can discuss mutual interests among like-minded enthusiasts. We look forward to visiting them daily, where we read fresh newly-created discussion threads, follow up on replies to posts we have made, and perhaps reach out individually to a fellow member or two that we have ongoing conversations with. We like to help others, just as we appreciate members helping us. Some forums are even graced by the presence of an industry member or celebrity.

Forums, also called discussion boards, have been around for a long time. Forums have their roots in a few early group communication systems, which still exist today. The Listserv (and similar) mailing lists are discussions participated in by e-mail, where list members mail their thoughts and replies to the list, where they are distributed for all list members to read. Usenet newsgroups are another means of group discussion, more closely resembling the forums we are familiar with.

Also, in the days of dial-up connections and text-based interfaces, you could dial into a BBS (bulletin board system), where you could not only download files but also take part in online conversations through their discussion groups. (The popular retailer Madisound Speaker Components hosted such discussions on their BBS.) In addition, you could find forums on the major online services that existed before the Internet became popular – CompuServe, GEnie, Prodigy and the younger upstart America Online (AOL) were the major players.

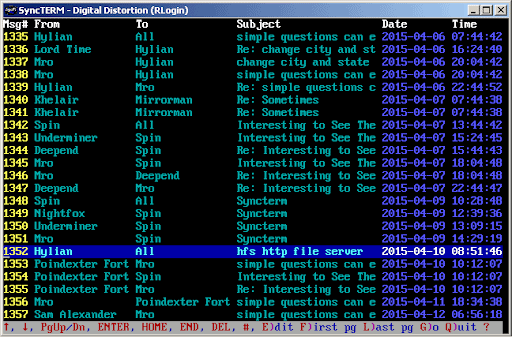

A screen shot in a terminal emulator of a message listing on an old BBS.

A screen shot in a terminal emulator of a message listing on an old BBS.

As the Internet became more popular, many of us signed up for dial-up accounts at ISPs – Internet Service Providers – where we could use the Internet without having to watch the clock like we had to with the online services, where they billed according to the time you spent on them. It wasn’t long before the online services began to lose subscribers, and more users flocked to the Internet. Businesses adopted the Internet as a means of marketing their products and services and to keep in touch with their customers. Other organizations offered a presence as well, and individuals went to great lengths to offer their unique knowledge and skills to create their own sites on the World Wide Web, some establishing Web-based forums and inviting others to participate.

A DOS dial-up screen shot.

A DOS dial-up screen shot.Along with the good came the bad. Spammers found it cheap and easy to mass e-mail Internet users by buying or hacking mailing lists or using trickery to obtain e-mail addresses. The dark web offered up all sorts of illicit and illegal diversions. The dark underbelly of Internet users would visit forums and guestbooks to stir up trouble and/or spew hateful messages, hiding behind their anonymity. And even if some users weren’t specifically out for flaming or harassing others, it did not take much to trigger negative responses in group discussions from a few of these individuals, who would make the group a miserable experience for all involved until that individual was blocked or chased away.

This is where my story begins. Having operated or moderated forums for over 25 years, I’ve experienced it all – the good and the bad, the many changes to forums and their users over time, and the continually changing tide of the Internet.

My history with online communities goes back to my time as a CompuServe subscriber. CompuServe hosted forums for various topics, everything from computer software and hardware support to all kinds of leisure interests. I first discovered a forum when I needed support for Novell Netware – I was troubleshooting a networking issue at our office, where I was the systems administrator. Once I realized there were other forums on CompuServe and saw that many of them were not based on technological topics, I set out to find a few that covered my interests.

I was a member of a handful of forums, including a Consumer Electronics forum (which split into separate audio and video forums due to volume). I was also a member of the Music/Arts Forum, where my increased activities (including writing music reviews) led to being offered a position as a “sysop,” their term for a forum moderator. The “wizops” had even higher privileges, closer to what forum administrators are today.

With users moving to the Internet and leaving CompuServe, I found I wanted a niche forum to discuss specific subjects without being tied to an online service. In 1997, a friend and I chipped in together for a hosting account to build Web sites for clients, and a few months later I registered my first couple of domain names and set up a forum. A few more forums soon followed, as I took on clients and suggested they engage with their fans or customers.