Ever since the Sony Walkman became a private music listening platform sensation in the late 1970s, headphone design and specs have continued to improve, with the consumer, professional and audiophile markets all progressing and slowly but inexorably blurring into each other.

The mainstream consumer has moved from the initial novelty of portable headphones to earbud ubiquity. The average pedestrian on the street in most metropolitan cities will, more often than not, be sporting earbuds and will either be listening to music or conducting a phone conversation. Ironically, the lower fidelity that resulted from the data compression of convenient mp3 files has caused a resurgence of interest in better sound-quality equipment to fill that void. Headphones, digital audio (digital to analog) converters or DACs, headphone amplifiers, in-ear monitors (IEMs), earbud tips, high-quality cables and connectors and other related gear have made great technological strides, both in terms of utilizing new materials and engineering in designs, as well as improved ergonomics to maximize the enjoyment of the listening experience.

CanJam NYC 2020, held on February 15 - 16 in Manhattan's New York Marriott Marquis in Times Square, demonstrated this trend in full. In stark contrast to Bluetooth iPod earbuds or garish, bass-heavy Beats (no offense to Dr. Dre), a competitively-priced range of consumer headphones and earbuds with phenomenally superior sound quality were showcased alongside new designs for professional studio recording, mixing and ultra-high-end audiophile-grade music listening environments. Additionally, numerous new companies, as well as long established ones, debuted their latest products, some of them successfully combining space-age engineering and hybrid materials with exotic woods to complement a retro aesthetic embrace of old school tech.

CanJam was surprisingly well attended, which demonstrated that the hunger for premium audio listening quality has resurfaced in this new era of private audio. A significant percentage of attendees to the New York show were millennials or even Gen Z kids still in middle school or high school.

Composer and producer David Chesky, who attended CanJam NYC 2020,

commented back in Copper #30 that “The younger generation is into taking their music with them. So I’ve seen this explosion in the headphone market.” This observation was undoubtedly corroborated by the overwhelming majority of millennial reps and entrepreneurs who had booths at CanJam.

This headphone explosion has been heard around the globe.

CanJam, which was founded by Jude Mansilla and Ethan Opolion of Head-Fi.org, started in 2006 and has grown internationally, with shows in Singapore, Shenzhen, London, and Shanghai, as well as in Chicago, Southern California and NYC.

In addition to the vendor and manufacturer showcase booths, CanJam 2020 NYC also sponsored a number of seminars, featuring:

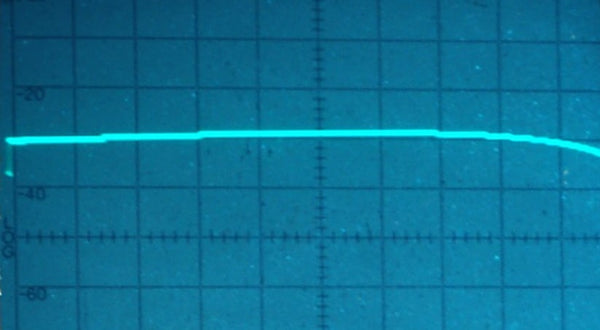

- The history of DAC design, from Rob Watts of Chord Electronics in the UK;

- Dan Foley of Audio Precision on total harmonic distortion (THD), the differences between actual listening vs. measured specs, and the testing of headphones vs. loudspeakers;

- Chinese CamJam sponsor Dunu held a seminar on its radical design innovations for its LUNA series;

- An open panel Q&A featuring Watts, Foley, representatives from Audeze, Dan Clark Audio, HEDD Audio, and others;

And lastly, a seminar to address the elephant in the room – probably be more akin to a dragon –the seemingly overnight influx of world-class-level in-ear and headphone designs and products that now come from China.

With nearly 100 different exhibitors covering the gamut from manufacturers to distributors and reps, CanJam NYC 2020 was comprehensive without becoming overwhelming. The dedication to quality was pervasive across the spectrum, with an impressive camaraderie not often seen among rival competitors in a niche market. The following (to be continued in Part Two of this report) are some impressive products and moments that left the biggest impressions on me:

Young Turks

The aforementioned new players in the field were making impressive presentations with some superb products. In-ear monitors (IEM) have become a standard in professional audio among musicians and singers as a way to deliver clearer monitor mixes, and preserve hearing and prevent tinnitus due to excessive SPL (sound pressure levels) that can occur at stage volumes especially when using traditional on-stage monitor speakers. While a great number of US and Chinese companies no carry IEM models in their catalogs, one company from Korea may have created the inside track in their effort to corner the working pro and semi pro musician’s market.

Launched in 2012, South Korea-based

AME Custom’s lineup of customized IEMs garnered a sizable amount of traffic to their table. With miniaturized (what AME calls “micro engineered) multiple drivers and a choice of jewellike abalone, mother of pearl, and custom-painted housings, AME’s IEMs had incredible instrument separation and offered excellent isolation from outside noise.

Earl Chon and JayZ Song of AME.

The AME triple-hybrid electrostatic

Radioso ($1,450) and 4-driver

Gravitas ($715) were especially outstanding. The Radioso features a low-frequency dynamic driver, mid-frequency balanced armature driver and four high-frequency electrostatic tweeters, hence the triple-hybrid designation. AME’s top-level 12-driver

J12U-12BA ($2,100) is one of AME’s best sellers in Japan. However, their most amazing offering, which AME rep Earl Chon told me was being especially aimed at the US market, was a single-driver IEM at a

$99.00 price that wasn’t even on their website yet: the J1U. In terms of bang for the buck, the J1U easily outperformed some of the costlier competitors’ IEM models and could conceivably displace the popular Shure SE535, a standard among working musicians – it’s that good.

The iFi Pro iCan headphone amp atop an iFi Pro iDSD DAC. Aftermarket headphone cables were in abundance at CanJam NYC. Why the Sharpies though?

With probably a good 90% or so of the exhibitors using high-resolution audio files or streaming sound sources like Spotify,

Andover Audio’s Model One Record Player was an excellent reminder for audio enthusiasts of the joys of pristine vinyl records and how their analog sound can differ markedly from digital. Founded in 2012 as a design company for hire in the consumer audio, telecom and auto industries, Andover’s flagship product under its own brand name is the Model One, a $2,500 self-contained record player system with a Pro-Ject Debut Carbon Espirit SB turntable, carbon fiber tonearm, and Ortofon OM2 cartridge.

The Andover Model One Record Player.

The Model One features four 3.5-inch aluminum woofers, dual air motion tweeters, and a 200-watts of bi-amplified Class D power, as well as a dedicated headphone amp. The latter was wonderfully full-sounding while listening to the Tedeschi Trucks Band’s,

Revelation LP. Andover’s open-backed

PM-50 Planar Magnetic Headphones ($500) were an excellent complement to the Model One for private listening. The Model One also is available with a subwoofer ($800) and LP storage cabinet options.

Westone, a popular player in the in-ear and IEM markets, had a number on display.

Hailing from Berwyn, IL outside of Chicago,

ZMF Headphones has been making high-end audio boutique products since 2011. A former student of acoustic guitar lutherie, founder Zach Mehrback has applied some of this training towards the design of ZMF’s headphone baffles, which are similar to acoustic guitar soundboards. ZMF’s product offerings are somewhat unique in their approach, which specifically caters to various listening tastes. Some of ZMF’s models include the warm sounding

Atticus ($1,099.99) with its mid-bass hump, the massive sounding sub-bass-pronounced

Eikon ($1,399.99), and the open airiness of the

Aeolus ($1,199.99).

A dazzling variety from ZMF.

Their top of the line

Verite ($2,499.99), available in both closed- and open-back configurations, sports vapor-deposited-beryllium drivers, and displayed a depth and breadth of sound that unmistakably added deeper colors to the music sources – a sonic enhancement that could be described as “larger than life.” Far from having a flat response, the ZMFs color sound, in my opinion, in many desirable ways that Apple’s Beats fail to or accomplish poorly. Listening to the pristine solo piano recordings of Ryuichi Sakamoto, recordings from Radiohead and orchestral film soundtracks, the Verite’s enhanced sound was like an aural version of Blu-Ray. The Verite’s specs cite sensitivity at 99 dB SPL/mw and a measured impedance of 300 ohms, thus making a smartphone output jack too weak to fully hear what the Verite can do.

ZMF Headphones come in a variety of hardwoods, chosen for sonic qualities as well as visual aesthetics. Choices include silkwood, sapele, cocobolo, pheasantwood, purple heart, ziricote, monkeypod, ironwood, leopardwood, maple, camphor, zebrawood, cherry, African blackwood, and Manchurian ash! They also come in a variety of ear pad shapes and densities, which can further tailor the sound from the neutral to the warm end of the spectrum.

Fidelice displayed striking electronics designed by studio legend Rupert Neve.

Old Dogs with New Tricks

With close to 60 years in the audio industry,

Audio-Technica has gone from becoming a turntable cartridge and stylus specialty company to a full-fledged pro and consumer audio titan, and one of the few Japanese companies other than Sony to successfully maintain its presence in both camps. A-T microphones have become a favorite of many recording artists in the studio, and their shotgun mics are a reliable standby on many film shoot locations.

However, the focus of the show was headphones, and A-T’s latest offerings, slated to hit the market in March 2020, were their exotic-wood-finished

ATH-AWKT ($1,899) and

ATH-AWAS ($1,399) audiophile over-ear headphones. Designed for comfort and performance, the ATH-AWKT and ATH-AWAS both utilize exotic hardwoods (striped ebony Kokutan for the AWKT and Asada Zakura ironwood for the AWAS) to suppress unwanted resonances, a proven technique in making hardwood loudspeaker cabinets.

Wood headphones from Audio-Technica.

The AWKT sports 53mm drivers configured in a Permendur magnetic circuit on a titanium flange with 6N-OFC voice coils to deliver a frequency response of 5Hz-45kHz. The AWAS has DLC (Diamond Like Coated) 53mm drivers in a pure iron yoke to provide 5Hz-42kHz response. Both models have A-T’s D.A.D.S. (Double Air Damping System), claimed to provide enhanced bass accuracy, as well as detachable cables with a choice of standard or 4-pin XLRM balanced connectors.

The new

ATH-WP900 headphones were also on display ($650), featuring flamed maple housings and the same DLC drivers as the above models. The WP900 delivers 5Hz-50kHz response.

Mytek Digital's electronics gave attendees an illuminating listening experience.

A-T headphones like the ATH-M50x are used in many recording studios along with Austrian and German stalwarts

AKG,

Sennheiser, and

Beyerdynamic, for their accurate reproduction. The AWKT and AWAS both exhibited aspects of the ATH-M50x but with a more luxurious feel and a “bigger” sound. A characteristic of some Japanese audio gear is a greater articulation in the highs and upper mids, bordering on icy crispness and lacking warmth and depth. The AWKT and AWAS do not share those traits.

For almost a century, Germany’s

Beyerdynamic has been designing and manufacturing top notch microphones and headphones. Their DT Series headphones are a favorite among video game enthusiasts, especially for their sense of surround-sound three dimensionality when playing virtual reality combat games. Of course, Beyer’s long history of supplying the audiophile market is well documented, but the company has stepped up its latest wireless offerings with their

Amiron ($599) and

Lagoon ANC ($299) Bluetooth headphones. Their Bluetooth

Aventho model ($299) is still popular and, the noise cancellation capabilities of the Lagoon and Aventho make them ideal for shutting out distractions on long plane or train trips. In addition to adjustable noise cancellation, the Lagoon folds up compactly, provides alerts for battery, high sound pressure levels, Bluetooth and other functions, and has a 10-meter Bluetooth distance range.

The beyerdynamic Amiron.

The Amiron were bulkier, but noticeably superior in terms of both the quality of the Bluetooth connection as well as their richer sound quality. While also wireless, the Amiron lacks the lightweight travel ease of the Lagoon, but the tradeoff in better fidelity makes it a worthwhile choice for the listener who wants to be able to roam around the room without an umbilical cord to their headphone amplifier or other signal source.

In designing headphones, the experimenting with new materials in the quest for improved performance can result in an exorbitant amount of R&D (research and development) expense. That hasn’t deterred

Fostex, long known for its DIY analog and digital recording equipment. The company premiered its

TH-900mk2 ($1,599), which comes with proprietary “Biodyna”-equipped 50mm drivers in a 1.5 tesla flux density Neodymium magnetic circuit, housed in a Urushi-lacquered Japanese cherry birch housing. Made from biocellulose fiber, Biodyna diaphragm specs are claimed to measure double the propagation velocity and offer 500% greater rigidity compared to conventional plastic-film-based drivers – all contributing to improved sound.

Headphones from Fostex.

The Fostex

TR50RPmk3 ($159.99) is a perennial favorite for small private recording studios and was available for comparison at the booth. The TH-900mk2 exhibited surprisingly few fundamental audio differences compared to the TR50RPmk3, although it delivered a greater spaciousness in its sound. Whether Fostex fans would love it enough to replace their TR50 standbys will be up to the individual, but Fostex is still pushing the envelope in its R&D, so where Biodyna engineering goes in the future is anybody’s guess. John Meyer of Meyer Sound has experimented with a slew of different driver materials and still uses treated paper, which is essentially a cellulose product. Can Biodyna be next?

In Part Two I’ll cover tube amp retro chic, the Dragon in the Room and more.

The house where Harry Pearson lived. Courtesy of

The house where Harry Pearson lived. Courtesy of

So Colfax now had this FM station, which had previously featured a religious-programming format. Colfax then shut down the station while they researched the competition, did some upgrades, built studios and hired a program director to assemble a staff and give it direction. Several radio industry consultants assured success, but agreed it would face a highly competitive format war.

A format was chosen, as the two stations currently doing that format in the Minneapolis area were thought to be weak. A marketing person was asked to come up with ideas for the new property. Apparently an entire book of ideas was presented, none of which would have worked – yet one slogan was brilliant and would subsequently be adopted.

Back in Syracuse, I had to sign an NDA (non-disclosure agreement), which I happily did, before they would tell me the new name of the station, as well as its format and slogan. When I found out the new name, I laughed and laughed, and actually had to put the phone down to gather my wits.

The new station would be called BOB. The slogan would be “Turn Your Knob to BOB.” The format would be New Country.

Searching for the call letters WBOB-FM, they were found to be owned by a disgruntled ex-wife, who had won the station and call letters in a divorce settlement and was happy to part with them for cash.

So Colfax now had this FM station, which had previously featured a religious-programming format. Colfax then shut down the station while they researched the competition, did some upgrades, built studios and hired a program director to assemble a staff and give it direction. Several radio industry consultants assured success, but agreed it would face a highly competitive format war.

A format was chosen, as the two stations currently doing that format in the Minneapolis area were thought to be weak. A marketing person was asked to come up with ideas for the new property. Apparently an entire book of ideas was presented, none of which would have worked – yet one slogan was brilliant and would subsequently be adopted.

Back in Syracuse, I had to sign an NDA (non-disclosure agreement), which I happily did, before they would tell me the new name of the station, as well as its format and slogan. When I found out the new name, I laughed and laughed, and actually had to put the phone down to gather my wits.

The new station would be called BOB. The slogan would be “Turn Your Knob to BOB.” The format would be New Country.

Searching for the call letters WBOB-FM, they were found to be owned by a disgruntled ex-wife, who had won the station and call letters in a divorce settlement and was happy to part with them for cash.

A studio was built in the KQQL space, and I set about finding personalities, building the music-playback algorithms and so on. Six weeks later, we launched with a million-dollar marketing budget – heavy TV, prime “super” billboards (the really large ones) and more.

A studio was built in the KQQL space, and I set about finding personalities, building the music-playback algorithms and so on. Six weeks later, we launched with a million-dollar marketing budget – heavy TV, prime “super” billboards (the really large ones) and more.

The WBOB-FM studio. When Bob spoke, people listened!

The WBOB-FM studio. When Bob spoke, people listened! Later, that company was sold to Clear Channel, which eventually became iHeartMedia. The rock station failed, and the former BOB/rock station was now smooth jazz. I was then given responsibility for that station in addition to KQQL.

Later, that company was sold to Clear Channel, which eventually became iHeartMedia. The rock station failed, and the former BOB/rock station was now smooth jazz. I was then given responsibility for that station in addition to KQQL.

One day, at an industry gala awards ceremony for which we were nominated for something or other, the president of Clear Channel came up to our table and without thinking, signaled I should “speak with my manager” as I had been a topic of conversation at their budget meetings. The handwriting was on the wall. Back home I confronted my boss and he told me they were “absorbing” my jobs. I had a no-cut contract so I was paid until it expired.

My wife grew up outside of Buffalo and had endured the snow of Syracuse, then Minneapolis, and wanted out of winter. We decided to move to Austin, Texas and had a home built.

My radio programming days were over.

Snapshots:

Upcoming country artists would sometimes visit my office and sing a few songs from their new albums. As an audiophile, this was good ear training for the intimate sound of live, un-amplified music. (Eventually the station built a dedicated performance space.)

Despite the fact that some of the artists had real talent, few made it to a national level of fame or success.

Talent doesn’t guarantee success. I believe the truth is that there’s a simple three-part map to success: talent, tenacity, luck.

I really enjoyed meeting so many artists, greatly respected their work ethic and wish that they all could have found fame, but only a few ever do.

One day, at an industry gala awards ceremony for which we were nominated for something or other, the president of Clear Channel came up to our table and without thinking, signaled I should “speak with my manager” as I had been a topic of conversation at their budget meetings. The handwriting was on the wall. Back home I confronted my boss and he told me they were “absorbing” my jobs. I had a no-cut contract so I was paid until it expired.

My wife grew up outside of Buffalo and had endured the snow of Syracuse, then Minneapolis, and wanted out of winter. We decided to move to Austin, Texas and had a home built.

My radio programming days were over.

Snapshots:

Upcoming country artists would sometimes visit my office and sing a few songs from their new albums. As an audiophile, this was good ear training for the intimate sound of live, un-amplified music. (Eventually the station built a dedicated performance space.)

Despite the fact that some of the artists had real talent, few made it to a national level of fame or success.

Talent doesn’t guarantee success. I believe the truth is that there’s a simple three-part map to success: talent, tenacity, luck.

I really enjoyed meeting so many artists, greatly respected their work ethic and wish that they all could have found fame, but only a few ever do.

Here she comes again! Dolly Parton and our man.

Here she comes again! Dolly Parton and our man.

Excerpt from the original Western Electric 300B data sheet.>

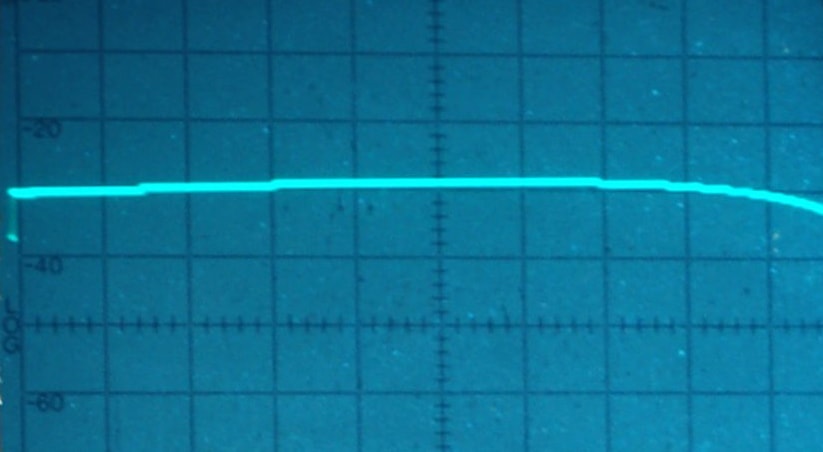

Excerpt from the original Western Electric 300B data sheet.> A transmitting triode tube in the lab, undergoing testing. Photo courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

A transmitting triode tube in the lab, undergoing testing. Photo courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.

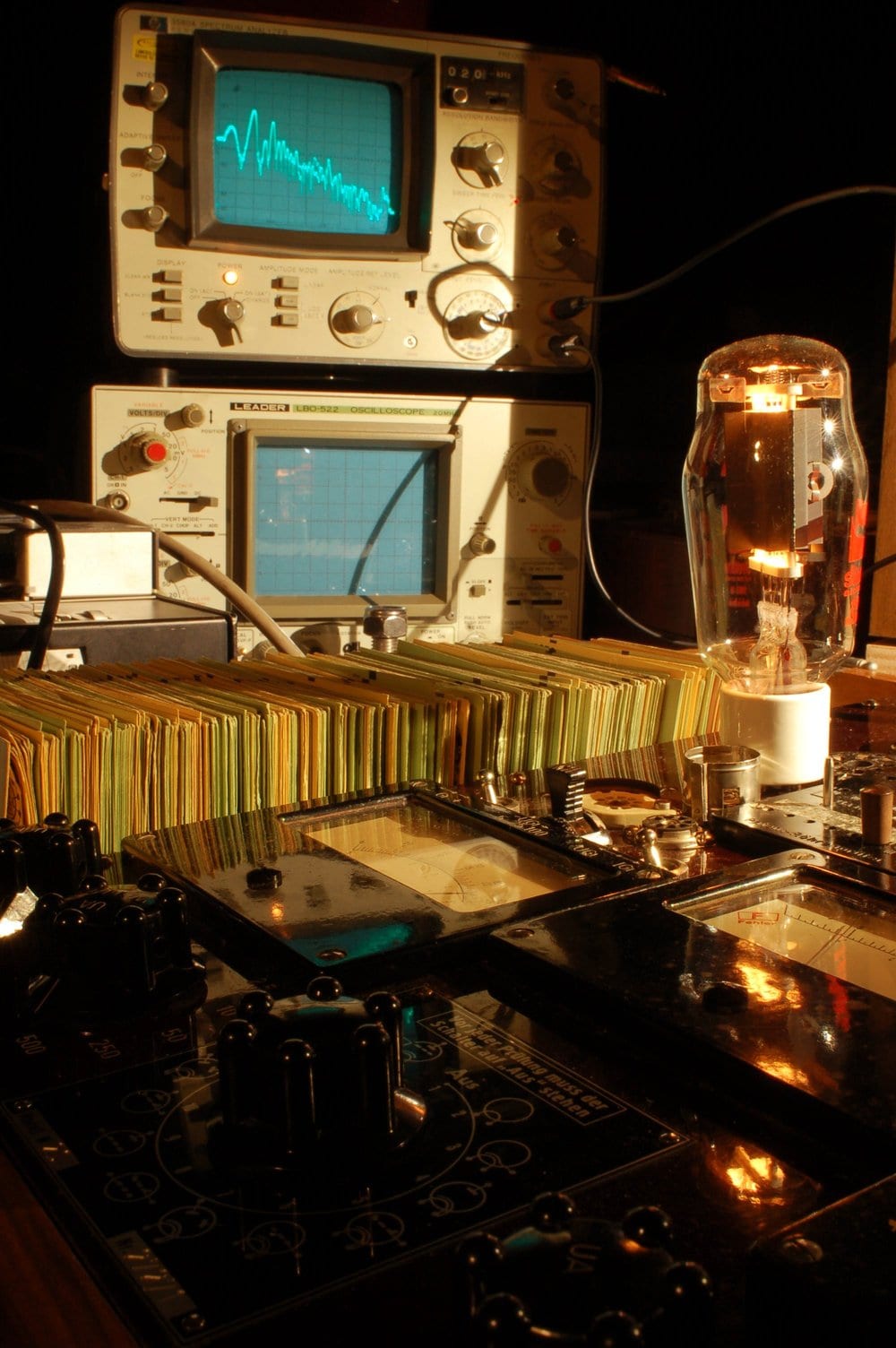

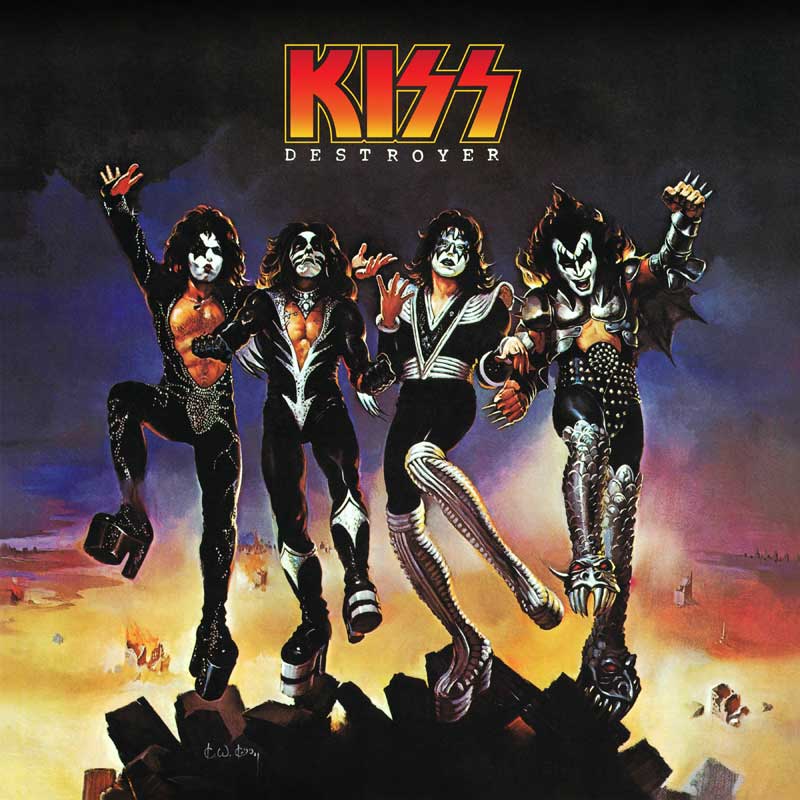

I have to move fast or we'll miss our plane home. I go to the front desk and they call a couple of cabs for us and we head off the airport. We just make the flight and an hour later we're landing at LaGuardia. Three limos are waiting to pick us up: one for drummer Peter Criss to take him to his East 30th Street apartment, another for lead guitarist Ace Frehley, who is heading to Tarrytown, NY, and the last one for Paul, me and bassist Gene Simmons, the guy who spits flames and is famous for sticking out his big tongue.

Ah, the glamorous life of a rock and roll road manager.

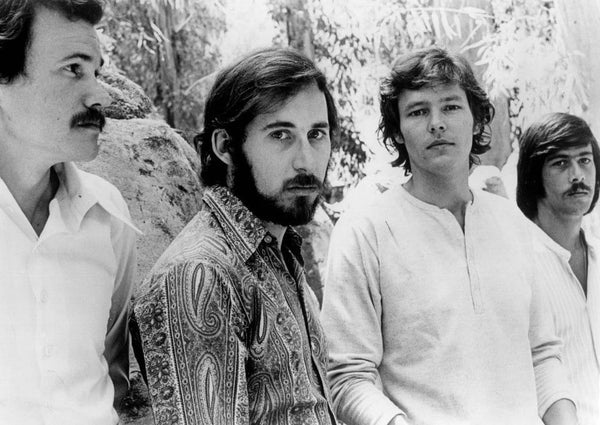

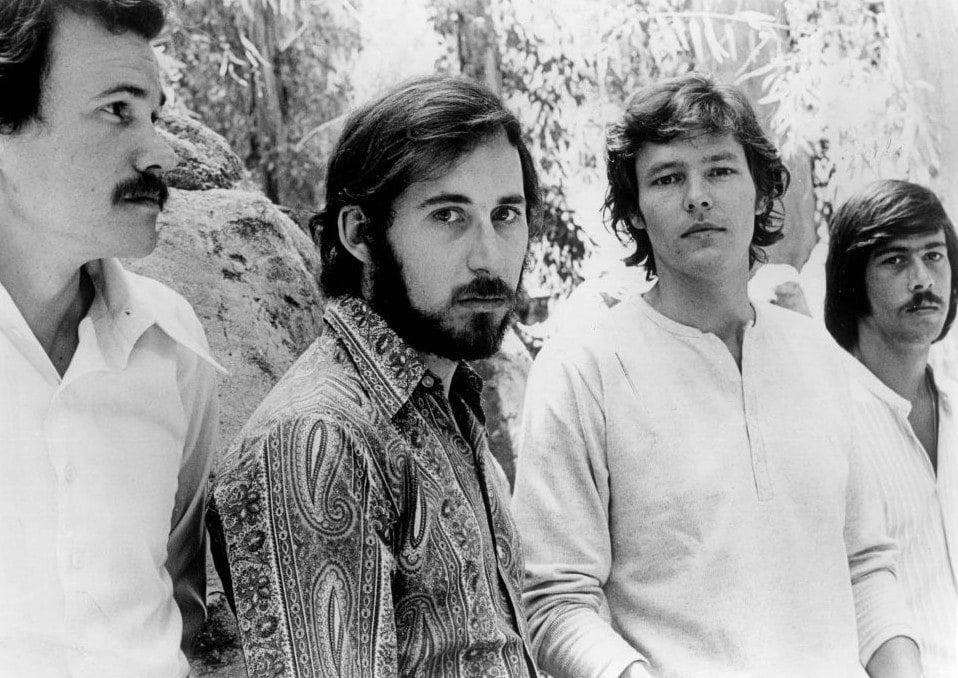

At this point, the tour is about a quarter of the way though and while my job is on top of the Kiss organization food chain, the pay won’t make me rich and it's not that much fun either. And the tour is such a big operation that, unlike other road managers, I don't have control over how the tour runs. When I was the road manager for mid-level rock groups like the Byrds or Jefferson Airplane, I was the go-to guy handling everything – the box office, road crew, travel arrangements, money, salaries, solving problems.

I have to move fast or we'll miss our plane home. I go to the front desk and they call a couple of cabs for us and we head off the airport. We just make the flight and an hour later we're landing at LaGuardia. Three limos are waiting to pick us up: one for drummer Peter Criss to take him to his East 30th Street apartment, another for lead guitarist Ace Frehley, who is heading to Tarrytown, NY, and the last one for Paul, me and bassist Gene Simmons, the guy who spits flames and is famous for sticking out his big tongue.

Ah, the glamorous life of a rock and roll road manager.

At this point, the tour is about a quarter of the way though and while my job is on top of the Kiss organization food chain, the pay won’t make me rich and it's not that much fun either. And the tour is such a big operation that, unlike other road managers, I don't have control over how the tour runs. When I was the road manager for mid-level rock groups like the Byrds or Jefferson Airplane, I was the go-to guy handling everything – the box office, road crew, travel arrangements, money, salaries, solving problems.

Ken contemplating life on the road.

Ken contemplating life on the road. Ken then...

Ken then... ...Ken now.

...Ken now.

The Lachrimae are usually played by an ensemble of viols of different sizes (bowed instruments similar to violin/viola/cello, but with frets across the fingerboards). In the new recording by the Opera Prima Consort (Brilliant Classics), led by Cristiano Contadin, the viols are joined by baroque violin (Fiorenza de Donatis and Andrea Rognoni), lute (Miguel Rincon), and recorder (Giulia Genini).

The result is a layered and impassioned sound – ideal for this repertoire exploring sadness. The “Lacrimae antiquae” (Ancient Tears) movement is a rich tapestry of desolation, with the Contandin’s ensemble phrasing in great, sighing breaths. The added textures of the non-viol instruments bring a new rugged dimension to the music.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHALTuaZndU&list=OLAK5uy_mzBuZ_IMG3mDwcQSGjB8lE2-R30z1UMdQ

For those who want to understand Dowland in the context of other composers for viol, Brilliant Classics also offers this Lacrimae as the first disc in a collection called Viola da Gamba Edition, which features a historical range of composers reaching all the way to J.S. Bach in the 18th century.

Another segment of Dowland’s instrumental-only output are his pieces for solo lute. That repertoire is represented on Dowland: Works for Lute (Performed on Guitar), played by English guitarist Michael Butten and released by First Hand Records.

Butten is a winner of the Julian Bream Prize, which the groundbreaking guitarist/lutenist (now 77), first-generation early-music advocate, founded and still judges himself. I can’t think of a more promising recommendation for a recording of Dowland transcriptions.

My anticipation was indeed rewarded. Butten’s playing is as accurate as it is sensitive, communicating a complete idea with each sentence and phrase. He keeps the contrapuntal voices separate and clear while shaping them into an intentional whole. Here’s the stately “Frog Galliard”:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P22WSzdGLt8&list=OLAK5uy_lEPQ36OG841VmY7gBRBIH-2BeHkU-VqoY&index=5

Parting caveat for those seeking further Dowland to stream: Beware a new two-volume set, The John Dowland Arrangements, by an entity called Nova Sonora Music. That’s not an early-music ensemble; turns out it’s a computer program. So, if you don’t like your Dowland played “in the robotic style,” you should steer well clear of this soulless digital travesty and spend your money on the work of musicians trained in early music who play physical, acoustic instruments!

The Lachrimae are usually played by an ensemble of viols of different sizes (bowed instruments similar to violin/viola/cello, but with frets across the fingerboards). In the new recording by the Opera Prima Consort (Brilliant Classics), led by Cristiano Contadin, the viols are joined by baroque violin (Fiorenza de Donatis and Andrea Rognoni), lute (Miguel Rincon), and recorder (Giulia Genini).

The result is a layered and impassioned sound – ideal for this repertoire exploring sadness. The “Lacrimae antiquae” (Ancient Tears) movement is a rich tapestry of desolation, with the Contandin’s ensemble phrasing in great, sighing breaths. The added textures of the non-viol instruments bring a new rugged dimension to the music.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHALTuaZndU&list=OLAK5uy_mzBuZ_IMG3mDwcQSGjB8lE2-R30z1UMdQ

For those who want to understand Dowland in the context of other composers for viol, Brilliant Classics also offers this Lacrimae as the first disc in a collection called Viola da Gamba Edition, which features a historical range of composers reaching all the way to J.S. Bach in the 18th century.

Another segment of Dowland’s instrumental-only output are his pieces for solo lute. That repertoire is represented on Dowland: Works for Lute (Performed on Guitar), played by English guitarist Michael Butten and released by First Hand Records.

Butten is a winner of the Julian Bream Prize, which the groundbreaking guitarist/lutenist (now 77), first-generation early-music advocate, founded and still judges himself. I can’t think of a more promising recommendation for a recording of Dowland transcriptions.

My anticipation was indeed rewarded. Butten’s playing is as accurate as it is sensitive, communicating a complete idea with each sentence and phrase. He keeps the contrapuntal voices separate and clear while shaping them into an intentional whole. Here’s the stately “Frog Galliard”:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P22WSzdGLt8&list=OLAK5uy_lEPQ36OG841VmY7gBRBIH-2BeHkU-VqoY&index=5

Parting caveat for those seeking further Dowland to stream: Beware a new two-volume set, The John Dowland Arrangements, by an entity called Nova Sonora Music. That’s not an early-music ensemble; turns out it’s a computer program. So, if you don’t like your Dowland played “in the robotic style,” you should steer well clear of this soulless digital travesty and spend your money on the work of musicians trained in early music who play physical, acoustic instruments!

Owsley "Bear" Stanley.

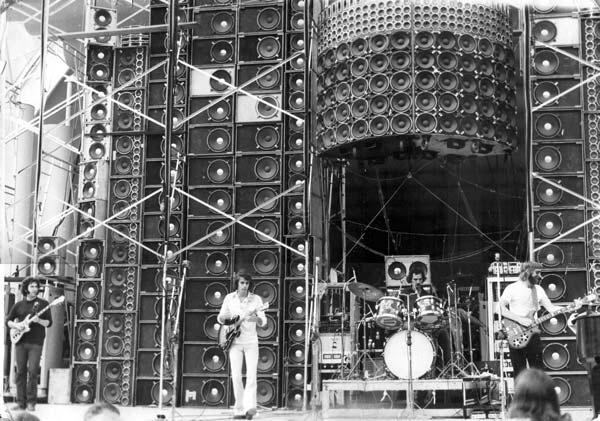

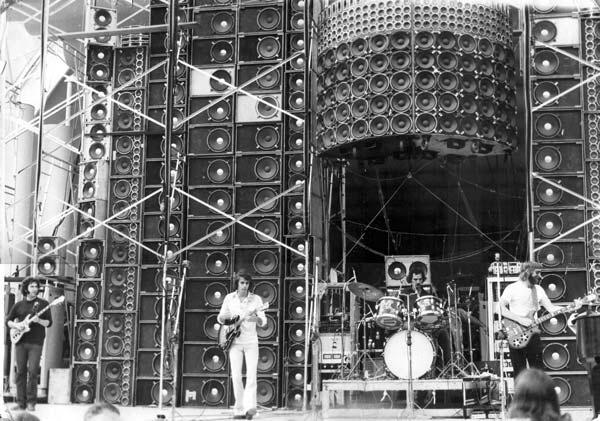

Owsley "Bear" Stanley. Stanley is credited with the design but long-time Dead sound man Dan Healy as well as crew members like Steve Parish, who had to build most of the equipment like the speaker cabinets and the scaffolding, were all heavily involved with the project.

Bear’s unique idea was to create a single sound source for each instrument and voice. Garcia had a single column of stacked speakers with very high gain, stacked in a way to multiply the sound and bring the guitar evenly to the audience anywhere from six feet to 600 feet away. Phil Lesh’s bass was channeled through a quadraphonic encoder that sent signals from each of the four strings to a separate channel and set of speakers for each string. In the documentary film Long Strange Trip Lesh related how much he loved that sound of his bass coming from four different spaces.

As Bear himself explained, “The entire system consisted of a cluster of line arrays that I developed and then tested in the way that line arrays work. Number one in a line array, if it’s composed of three different clusters, each of which is a certain frequency range with a crossover, then the bass is the longest column of speakers, the midrange is shorter, and the highs are shorter than that. But, much like a radio transmitter, they must all be the same radiating length. Each array must be as wide as it is tall or it doesn’t work right, and you can’t hang them in isolation.”

Man, I understand about half of dat.

The stage system stood forty feet high and seventy feet wide and sported 88 15 inch JBL speakers, 174 12-inch JBL speakers, 288 5-inch JBL speakers, (dude, remember how popular JBLs were?) and 54 Electro-Voice tweeters. The sound was powered by 26,000 watts generated by 55 McIntosh MC2300 amps. Giddyup.

The system was designed to be positioned behind the band so that they were hearing the same sound as the audience. Bear and John Curl from Alembic (yes, that John Curl) had to design a special microphone system to prevent feedback. They placed matched pairs of condenser microphones spaced 60 mm apart and run out of phase with each other. The vocalist sang into the top microphone, and the lower mic picked up whatever other sound was present in the stage environment. The signals were then added together using a differential summing amp, so that the sound common to both mics (the stage sound coming from the Wall) was canceled, and only the vocals were amplified. Yer kidding. This from a kid who didn’t graduate high school.

All of this required a crew of sixteen, two sets of scaffolding, and four semis to haul the stuff around. Setting up the Wall of Sound was so time-intensive that the crews would leapfrog each other, sending a crew and a set of scaffolding ahead to start setting up the next gig before the first gig was even torn down. I’ve seen film of this beast being setup and it’s scary stuff.

Grateful Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann was quoted describing the Wall of Sound as “Owsley’s brain in material form.” It accomplished what the Dead were after but Bear had created a monster that had a life of its own, was not friendly and could not be domesticated. Sound-wise everyone agreed it was gorgeous. But it was ultimately part of a journey. Debuting in its first form in February 1973 at Stanford University’s Maples Pavilion, every tweeter blew at the onset of the Dead’s first number. Sparks and lights flashing. Crowd went wild.

The bugs were worked out and the completed version was in place in March 1974 for the tour beginning at the Cow Palace in Daly City, CA.

But by October serious friction arose in the band. The demands of the high payroll, the costs of hauling stuff around and the weirdness of heavy drug use was wearing everyone down. The Grateful Dead decided to go on hiatus, and when they began touring again in 1976 the Wall of Sound had been dismantled and a more logistical-friendly touring setup put in place.

When the Dead did begin touring again Bear was replaced with Dan Healy at the mixing board. Phil Lesh hired Stanley as his personal roadie and Bear did accompany the band on their Egypt gig in 1978. But after their return to the states Stanley never worked for the band again. He was hired by Jefferson Starship as their onstage monitor mixer but that ended in 1979 and so did Bear’s career as a soundman.

In 1984 Stanley had become convinced a second ice age was coming. Bear tried to convince everyone around him to move to Australia, in his mind the safest refuge. He moved and eventually squatted on 126 acres in a rural corner of northeast Australia near Atherton in Queensland. It took the local authorities two years to realize he was there. By then Bear had built sheds, a reticulated water system, a septic system and a nine-kilowatt generator to provide electricity.

The authorities were not happy and tried to get rid of Stanley, but he had managed to build and maintain a viable farm and a two-family community in what was generously a no-man’s land. And no one was ever more ready for a fight than our boy. Ultimately the locals agreed to give him 26 acres, which Bear felt wasn’t enough. So he hired a crew and fenced in the entire 126 acres. By the time the dust settled he had a 99-year lease on the land.

And of course he turned it into what Bob Weir would call “a sort of science fiction version” of the hippie communes. He’d acquired portable and diesel generators. He installed two solar energy systems and a wind generator on a hundred-foot-high tower.

Stanley married and traveled back and forth from Australia to the States, keeping in touch with friends. As he got older his health began declining and in 2004 he was diagnosed with stage IV squamous cell carcinoma. He beat the disease but only barely. Even after a full recovery he had trouble swallowing and had to drink all of his food. The radiation therapy had been aggressive and caused weight loss, muscle problems in his neck and speech problems. His wife Sheila related they determined later that the doctors had over-dosed on the radiation and Bear was lucky to be alive.

Stanley had been a fighter his entire life; a disease was not going to get him. He would be all right with what would get him. On March 12, 2007 Bear was traveling with his wife Sheila on the dicey road to their compound when the car went off the road. She made it, Bear did not. He was survived by his wife, four children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

***

This has been a fun look into a genius and fevered mind. Owsley “Bear” Stanley’s contributions to the Grateful Dead in general and specifically their philosophy on live sound quality are evident in his legacy and his gift to us all: the thousands of feet of live tapes of the Grateful Dead’s performances while he did sound as a part of the Dead family. I have thoroughly enjoyed this journey and my hope is you have as well.

If you just can’t get enough about Bear I suggest you read Robert Greenfield’s Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III which was invaluable in my research. Bear’s website,

Stanley is credited with the design but long-time Dead sound man Dan Healy as well as crew members like Steve Parish, who had to build most of the equipment like the speaker cabinets and the scaffolding, were all heavily involved with the project.

Bear’s unique idea was to create a single sound source for each instrument and voice. Garcia had a single column of stacked speakers with very high gain, stacked in a way to multiply the sound and bring the guitar evenly to the audience anywhere from six feet to 600 feet away. Phil Lesh’s bass was channeled through a quadraphonic encoder that sent signals from each of the four strings to a separate channel and set of speakers for each string. In the documentary film Long Strange Trip Lesh related how much he loved that sound of his bass coming from four different spaces.

As Bear himself explained, “The entire system consisted of a cluster of line arrays that I developed and then tested in the way that line arrays work. Number one in a line array, if it’s composed of three different clusters, each of which is a certain frequency range with a crossover, then the bass is the longest column of speakers, the midrange is shorter, and the highs are shorter than that. But, much like a radio transmitter, they must all be the same radiating length. Each array must be as wide as it is tall or it doesn’t work right, and you can’t hang them in isolation.”

Man, I understand about half of dat.

The stage system stood forty feet high and seventy feet wide and sported 88 15 inch JBL speakers, 174 12-inch JBL speakers, 288 5-inch JBL speakers, (dude, remember how popular JBLs were?) and 54 Electro-Voice tweeters. The sound was powered by 26,000 watts generated by 55 McIntosh MC2300 amps. Giddyup.

The system was designed to be positioned behind the band so that they were hearing the same sound as the audience. Bear and John Curl from Alembic (yes, that John Curl) had to design a special microphone system to prevent feedback. They placed matched pairs of condenser microphones spaced 60 mm apart and run out of phase with each other. The vocalist sang into the top microphone, and the lower mic picked up whatever other sound was present in the stage environment. The signals were then added together using a differential summing amp, so that the sound common to both mics (the stage sound coming from the Wall) was canceled, and only the vocals were amplified. Yer kidding. This from a kid who didn’t graduate high school.

All of this required a crew of sixteen, two sets of scaffolding, and four semis to haul the stuff around. Setting up the Wall of Sound was so time-intensive that the crews would leapfrog each other, sending a crew and a set of scaffolding ahead to start setting up the next gig before the first gig was even torn down. I’ve seen film of this beast being setup and it’s scary stuff.

Grateful Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann was quoted describing the Wall of Sound as “Owsley’s brain in material form.” It accomplished what the Dead were after but Bear had created a monster that had a life of its own, was not friendly and could not be domesticated. Sound-wise everyone agreed it was gorgeous. But it was ultimately part of a journey. Debuting in its first form in February 1973 at Stanford University’s Maples Pavilion, every tweeter blew at the onset of the Dead’s first number. Sparks and lights flashing. Crowd went wild.

The bugs were worked out and the completed version was in place in March 1974 for the tour beginning at the Cow Palace in Daly City, CA.

But by October serious friction arose in the band. The demands of the high payroll, the costs of hauling stuff around and the weirdness of heavy drug use was wearing everyone down. The Grateful Dead decided to go on hiatus, and when they began touring again in 1976 the Wall of Sound had been dismantled and a more logistical-friendly touring setup put in place.

When the Dead did begin touring again Bear was replaced with Dan Healy at the mixing board. Phil Lesh hired Stanley as his personal roadie and Bear did accompany the band on their Egypt gig in 1978. But after their return to the states Stanley never worked for the band again. He was hired by Jefferson Starship as their onstage monitor mixer but that ended in 1979 and so did Bear’s career as a soundman.

In 1984 Stanley had become convinced a second ice age was coming. Bear tried to convince everyone around him to move to Australia, in his mind the safest refuge. He moved and eventually squatted on 126 acres in a rural corner of northeast Australia near Atherton in Queensland. It took the local authorities two years to realize he was there. By then Bear had built sheds, a reticulated water system, a septic system and a nine-kilowatt generator to provide electricity.

The authorities were not happy and tried to get rid of Stanley, but he had managed to build and maintain a viable farm and a two-family community in what was generously a no-man’s land. And no one was ever more ready for a fight than our boy. Ultimately the locals agreed to give him 26 acres, which Bear felt wasn’t enough. So he hired a crew and fenced in the entire 126 acres. By the time the dust settled he had a 99-year lease on the land.

And of course he turned it into what Bob Weir would call “a sort of science fiction version” of the hippie communes. He’d acquired portable and diesel generators. He installed two solar energy systems and a wind generator on a hundred-foot-high tower.

Stanley married and traveled back and forth from Australia to the States, keeping in touch with friends. As he got older his health began declining and in 2004 he was diagnosed with stage IV squamous cell carcinoma. He beat the disease but only barely. Even after a full recovery he had trouble swallowing and had to drink all of his food. The radiation therapy had been aggressive and caused weight loss, muscle problems in his neck and speech problems. His wife Sheila related they determined later that the doctors had over-dosed on the radiation and Bear was lucky to be alive.

Stanley had been a fighter his entire life; a disease was not going to get him. He would be all right with what would get him. On March 12, 2007 Bear was traveling with his wife Sheila on the dicey road to their compound when the car went off the road. She made it, Bear did not. He was survived by his wife, four children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

***

This has been a fun look into a genius and fevered mind. Owsley “Bear” Stanley’s contributions to the Grateful Dead in general and specifically their philosophy on live sound quality are evident in his legacy and his gift to us all: the thousands of feet of live tapes of the Grateful Dead’s performances while he did sound as a part of the Dead family. I have thoroughly enjoyed this journey and my hope is you have as well.

If you just can’t get enough about Bear I suggest you read Robert Greenfield’s Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III which was invaluable in my research. Bear’s website,

Composer and producer David Chesky, who attended CanJam NYC 2020,

Composer and producer David Chesky, who attended CanJam NYC 2020,  Earl Chon and JayZ Song of AME.

Earl Chon and JayZ Song of AME. The iFi Pro iCan headphone amp atop an iFi Pro iDSD DAC. Aftermarket headphone cables were in abundance at CanJam NYC. Why the Sharpies though?

The iFi Pro iCan headphone amp atop an iFi Pro iDSD DAC. Aftermarket headphone cables were in abundance at CanJam NYC. Why the Sharpies though? The Andover Model One Record Player.

The Andover Model One Record Player. Westone, a popular player in the in-ear and IEM markets, had a number on display.

Westone, a popular player in the in-ear and IEM markets, had a number on display. A dazzling variety from ZMF.

A dazzling variety from ZMF. Fidelice displayed striking electronics designed by studio legend Rupert Neve.

Fidelice displayed striking electronics designed by studio legend Rupert Neve. Wood headphones from Audio-Technica.

Wood headphones from Audio-Technica. Mytek Digital's electronics gave attendees an illuminating listening experience.

Mytek Digital's electronics gave attendees an illuminating listening experience. The beyerdynamic Amiron.

The beyerdynamic Amiron. Headphones from Fostex.

Headphones from Fostex.

Beach Bunny - Honeymoon

The brainchild of Chicagoan Lily Trifilio, Beach Bunny is an indie garage-pop band that’s released four EPs over the last four years. The last of those, Prom Queen, was released in 2018; the title track has gotten the band more than 40 million streams on Spotify. “Prom Queen” (the song) dealt with negative-body issues, and has gained a huge boost in popularity from the currently red hot video app TikTok, where it can apparently be heard virtually non-stop. That exposure got them a record deal with New York indie label Mom+Pop Records and Honeymoon—Beach Bunny’s first full-length album—has these guys poised for the big time. Whereas their EPs tended to be mostly lo-fi, acoustic bedroom-pop type productions; the band has been touring for a couple of years now, and the sound has definitely gelled and gotten bigger and bolder—and much more ready for prime time.

Lily Trifilio writes songs that are tuneful and energetic, and very confessional in nature; and they’re absolutely brimming with infectious pop hooks! A graduate of DePaul University in Chicago, she was even called upon recently by her alma mater to teach a master class in songwriting. I’d say the style the band has adopted now is more along the lines of “power fuzz-pop” and possibly even closer to “fuzz-pop/post-punk.” In the song “Rearview,” she asks a former lover, “Was I ever good enough for you...you always seem closer in the rearview.” The song lopes along with strumming guitar and organ accompaniment for two-and-quarter minutes, then drummer John Alvarado blasts into the tune and the band absolutely cranks for the last thirty seconds. The effect is truly stunning!

Of course YMMV, but I find it exciting that groups like this can transition from internet splash to actual, touring, working band, while making music that is both interesting and fun to listen to. Hey, there’s nothing here that’s ultimately heavy or compellingly classic—and most of the songs clock in at about two minutes, tops. But it beats the hell out of whatever crap Taylor Swift is cranking over the pop airwaves these days. Recommended.

Mom + Pop Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Bandcamp, Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Apple Music, iTunes, Spotify)

Beach Bunny - Honeymoon

The brainchild of Chicagoan Lily Trifilio, Beach Bunny is an indie garage-pop band that’s released four EPs over the last four years. The last of those, Prom Queen, was released in 2018; the title track has gotten the band more than 40 million streams on Spotify. “Prom Queen” (the song) dealt with negative-body issues, and has gained a huge boost in popularity from the currently red hot video app TikTok, where it can apparently be heard virtually non-stop. That exposure got them a record deal with New York indie label Mom+Pop Records and Honeymoon—Beach Bunny’s first full-length album—has these guys poised for the big time. Whereas their EPs tended to be mostly lo-fi, acoustic bedroom-pop type productions; the band has been touring for a couple of years now, and the sound has definitely gelled and gotten bigger and bolder—and much more ready for prime time.

Lily Trifilio writes songs that are tuneful and energetic, and very confessional in nature; and they’re absolutely brimming with infectious pop hooks! A graduate of DePaul University in Chicago, she was even called upon recently by her alma mater to teach a master class in songwriting. I’d say the style the band has adopted now is more along the lines of “power fuzz-pop” and possibly even closer to “fuzz-pop/post-punk.” In the song “Rearview,” she asks a former lover, “Was I ever good enough for you...you always seem closer in the rearview.” The song lopes along with strumming guitar and organ accompaniment for two-and-quarter minutes, then drummer John Alvarado blasts into the tune and the band absolutely cranks for the last thirty seconds. The effect is truly stunning!

Of course YMMV, but I find it exciting that groups like this can transition from internet splash to actual, touring, working band, while making music that is both interesting and fun to listen to. Hey, there’s nothing here that’s ultimately heavy or compellingly classic—and most of the songs clock in at about two minutes, tops. But it beats the hell out of whatever crap Taylor Swift is cranking over the pop airwaves these days. Recommended.

Mom + Pop Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Bandcamp, Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Apple Music, iTunes, Spotify)

Anoushka Shankar - Love Letters

I probably first heard the sitar played by George Harrison on a Beatles record, but at the time, it didn’t really register that it was an exotic Indian instrument I was hearing. I really didn’t make the sitar connection until George Harrison released his epic Concert for Bangladesh live album, where the Ravi Shankar played “Bangla Dhun” was the opener. And it was literally, criminally ignored by nearly everyone who ever bought the record! I don’t know why, but Shankar’s playing truly resonated with me; I virtually couldn’t play any of the record’s sides without first listening to the “Bangla Dhun.” I bought Anoushka Shankar’s (Ravi Shankar’s daughter) debut album at Tower Records in 1998 when it was first released, and have revisited it regularly over the years. It’s more in the classical Indian music vein, a direction that Anoushka has strayed from over the last decade or so, moving more into the world music arena. And combining elements of pop, trance, and fusion, among her many influences that meld surprisingly well with her heavy Indian classical background.

Five years later, in 2003, Norah Jones literally swept the Grammy Awards with her debut album, and suddenly, it became known that she and Anoushka Shankar were sisters. I don’t know with certainty what influence this had on Anoushka Shankar’s career, but it seemed to definitely veer from that point towards more popular music. This new EP comes in the wake of two life-changing events for her; a serious health crisis, requiring numerous surgeries and where she quite nearly died. And the dissolution of her seven-year marriage to British film director Joe Wright (Darkest Hour, Atonement, Pride & Prejudice); obviously, she has struggled with the aftermath of both mightily. And this new album is her way of announcing to the world that she’s ready to move on.

The six songs deal mostly with love and loss; I get the feeling from listening to the songs that she’s moved on from her health issues, but is still attempting to process and externalize what the breakup of her marriage has put her through, and how she’s continuing to deal with it. I don’t know any of the details, but you get the idea from some of the song lyrics that her ex ditched her for a younger woman. In the song “Bright Eyes,” Anoushka asks, “Does she feel younger than me, new and shiny” and “most importantly, do you call her Bright Eyes too?” She grapples with issues of self-doubt, like in the song “Lovable,” where she asks, “Am I still lovable, since you stopped loving me?”

The record is very sparsely arranged, with most of the songs only containing Anoushka’s sitar, along with an acoustic bass and a variety of Indian percussive instruments. A few songs add piano to the mix, and all of the songs contain vocals from the likes of German singer Alev Lenz, the Afro-French Cuban duo Ibeyi, and Indian singer Shilpa Rao. All of the songs except for “These Words” are sung in English. I’m gonna be perfectly honest with you—this is an absolute downer of a listening experience. But the songs are absolutely beautiful, and Anoushka’s instrument tone is simply gorgeous—this is an extremely well-recorded EP. I did all my listening to the MQA files on Tidal, and I felt the sound was remarkable. Well worth a listen if you have a chance!

Mercury/Universal France, (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer, YouTube)

Anoushka Shankar - Love Letters

I probably first heard the sitar played by George Harrison on a Beatles record, but at the time, it didn’t really register that it was an exotic Indian instrument I was hearing. I really didn’t make the sitar connection until George Harrison released his epic Concert for Bangladesh live album, where the Ravi Shankar played “Bangla Dhun” was the opener. And it was literally, criminally ignored by nearly everyone who ever bought the record! I don’t know why, but Shankar’s playing truly resonated with me; I virtually couldn’t play any of the record’s sides without first listening to the “Bangla Dhun.” I bought Anoushka Shankar’s (Ravi Shankar’s daughter) debut album at Tower Records in 1998 when it was first released, and have revisited it regularly over the years. It’s more in the classical Indian music vein, a direction that Anoushka has strayed from over the last decade or so, moving more into the world music arena. And combining elements of pop, trance, and fusion, among her many influences that meld surprisingly well with her heavy Indian classical background.

Five years later, in 2003, Norah Jones literally swept the Grammy Awards with her debut album, and suddenly, it became known that she and Anoushka Shankar were sisters. I don’t know with certainty what influence this had on Anoushka Shankar’s career, but it seemed to definitely veer from that point towards more popular music. This new EP comes in the wake of two life-changing events for her; a serious health crisis, requiring numerous surgeries and where she quite nearly died. And the dissolution of her seven-year marriage to British film director Joe Wright (Darkest Hour, Atonement, Pride & Prejudice); obviously, she has struggled with the aftermath of both mightily. And this new album is her way of announcing to the world that she’s ready to move on.

The six songs deal mostly with love and loss; I get the feeling from listening to the songs that she’s moved on from her health issues, but is still attempting to process and externalize what the breakup of her marriage has put her through, and how she’s continuing to deal with it. I don’t know any of the details, but you get the idea from some of the song lyrics that her ex ditched her for a younger woman. In the song “Bright Eyes,” Anoushka asks, “Does she feel younger than me, new and shiny” and “most importantly, do you call her Bright Eyes too?” She grapples with issues of self-doubt, like in the song “Lovable,” where she asks, “Am I still lovable, since you stopped loving me?”

The record is very sparsely arranged, with most of the songs only containing Anoushka’s sitar, along with an acoustic bass and a variety of Indian percussive instruments. A few songs add piano to the mix, and all of the songs contain vocals from the likes of German singer Alev Lenz, the Afro-French Cuban duo Ibeyi, and Indian singer Shilpa Rao. All of the songs except for “These Words” are sung in English. I’m gonna be perfectly honest with you—this is an absolute downer of a listening experience. But the songs are absolutely beautiful, and Anoushka’s instrument tone is simply gorgeous—this is an extremely well-recorded EP. I did all my listening to the MQA files on Tidal, and I felt the sound was remarkable. Well worth a listen if you have a chance!

Mercury/Universal France, (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer, YouTube)

Ben Watt - Storm Damage

Most everyone knows Benn Watt as one-half of the EDM/Dance/Trance/Jazz/Bossa/Electronica powerhouse Everything But the Girl, with wife, partner, and powerhouse vocalist Tracey Thorn. And he’s also a talented multi-instrumentalist, producer, and DJ, who’s worked with just about everyone who really matters in the music industry. Everything But the Girl enjoyed tremendous success through the late eighties and into the nineties with an acoustic jazz/bossa/dance slant, but then Watt became gravely ill with an extremely rare autoimmune disease and quite nearly died. His eventually return to music found him getting very deeply steeped in techno, deep house, and club music, and EBTG’s return reaped even greater commercial successes than ever before. The group went on hiatus in 2000, but Watt hasn’t slowed down at all; he’s continued to produce and record with acts as diverse as Beth Orton, Massive Attack, and David Gilmour.

This new album shows a return to his singer/songwriter roots from very early on in his career, and chronicles his process of coping with the recent death of his closest half-brother in 2016. The aftermath found him grieving, angry, and disillusioned over the disintegrating political landscape in England; it basically muted his creative voice for over a year. His return is marked by this new album, Storm Damage, which he refers to as a “future-retro trio”; it basically features a foundation of piano, upright bass, and hybrid acoustic-electronic drums on all the songs. And of course, the songs are augmented by guitars (Low’s Alan Sparhawk guests on several songs), synths, and samples that Watt calls “impressionistic found sounds” that he adapted from online public-domain recording archives. Despite the embellishments, this remains a sparsely instrumented album, and is a return to the more organic roots of his early career. Much of the focus of the record is on Watt’s vocals and the confessional nature of most of the songs.

The press notes for the release state Watt’s desire for “a new way to capture the energy,” and he’s most definitely done that with this new album. “Summer Ghosts” opens with the lines, “Thought I had a degree of resistance, but look at me seeking assistance.” Watt makes no bones about the fact that he’s struggling with all the complications of his current environment. It follows the basic piano/bass/drums formula of most of the album, but the added analogue synths float over the acoustic foundation, and give the song a very ethereal and atmospheric vibe. In the song “You’ve Changed, I’ve Changed,” he states, “You’ve changed, I’ve changed, we can’t all remain the same. Shed the skin, it’s no big thing.” Time to move on, get over it. It’s a record of very deep introspection.

The recorded sound is superb, and features many of the atmospheric qualities that he brought to all the EBTG recordings; the streamed MQA sound from Tidal sounded simply incredible over my home system. It’s available from a variety of streaming services, and is well worth checking out—while it’s nothing like most of his techno and deep house output, it’s nonetheless a compelling listen. Highly recommended.

Ultimate Road/Caroline, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Ben Watt - Storm Damage

Most everyone knows Benn Watt as one-half of the EDM/Dance/Trance/Jazz/Bossa/Electronica powerhouse Everything But the Girl, with wife, partner, and powerhouse vocalist Tracey Thorn. And he’s also a talented multi-instrumentalist, producer, and DJ, who’s worked with just about everyone who really matters in the music industry. Everything But the Girl enjoyed tremendous success through the late eighties and into the nineties with an acoustic jazz/bossa/dance slant, but then Watt became gravely ill with an extremely rare autoimmune disease and quite nearly died. His eventually return to music found him getting very deeply steeped in techno, deep house, and club music, and EBTG’s return reaped even greater commercial successes than ever before. The group went on hiatus in 2000, but Watt hasn’t slowed down at all; he’s continued to produce and record with acts as diverse as Beth Orton, Massive Attack, and David Gilmour.

This new album shows a return to his singer/songwriter roots from very early on in his career, and chronicles his process of coping with the recent death of his closest half-brother in 2016. The aftermath found him grieving, angry, and disillusioned over the disintegrating political landscape in England; it basically muted his creative voice for over a year. His return is marked by this new album, Storm Damage, which he refers to as a “future-retro trio”; it basically features a foundation of piano, upright bass, and hybrid acoustic-electronic drums on all the songs. And of course, the songs are augmented by guitars (Low’s Alan Sparhawk guests on several songs), synths, and samples that Watt calls “impressionistic found sounds” that he adapted from online public-domain recording archives. Despite the embellishments, this remains a sparsely instrumented album, and is a return to the more organic roots of his early career. Much of the focus of the record is on Watt’s vocals and the confessional nature of most of the songs.

The press notes for the release state Watt’s desire for “a new way to capture the energy,” and he’s most definitely done that with this new album. “Summer Ghosts” opens with the lines, “Thought I had a degree of resistance, but look at me seeking assistance.” Watt makes no bones about the fact that he’s struggling with all the complications of his current environment. It follows the basic piano/bass/drums formula of most of the album, but the added analogue synths float over the acoustic foundation, and give the song a very ethereal and atmospheric vibe. In the song “You’ve Changed, I’ve Changed,” he states, “You’ve changed, I’ve changed, we can’t all remain the same. Shed the skin, it’s no big thing.” Time to move on, get over it. It’s a record of very deep introspection.

The recorded sound is superb, and features many of the atmospheric qualities that he brought to all the EBTG recordings; the streamed MQA sound from Tidal sounded simply incredible over my home system. It’s available from a variety of streaming services, and is well worth checking out—while it’s nothing like most of his techno and deep house output, it’s nonetheless a compelling listen. Highly recommended.

Ultimate Road/Caroline, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, Google Play Music, Spotify, Deezer)

Carla Bley/Steve Swallow/Andy Sheppard - Life Goes On

Carla Bley has essentially been an active recording artist for sixty years. That’s right—sixty years! Born in 1938 in Oakland, California; her father was a piano teacher and church choirmaster, who taught her at a very young age to play the piano. However, he died when she was only eight years old, and by fourteen, she had decided that being a professional roller skater was her calling. She headed to New York City at seventeen, and took a job as a cigarette girl at legendary jazz club Birdland, where she immediately drew the attention of pianist Paul Bley. Who encouraged her piano playing, and also encouraged her to start composing—within a few years, they were married, and a number of other jazz artists were recording her compositions.

Carla Bley, at age 81, is one of the most prolific jazz composers of all time. I can’t even count the number of studio albums she has to her credit; double that number, and you get the number of albums she’s either collaborated or guested on. Her new album, Life Goes On, features longtime partner and collaborator, bassist Steve Swallow, along with tenor and soprano sax player Andy Sheppard. The trio have been playing together for over twenty-five years; this new record is their fourth album together. To hear the intricate and incredibly nuanced playing on this album, you’d never guess the ages of the players; Steve Swallow is 79, and Andy Sheppard is the youngster of the group at 63!

Life Goes On is a trio of relatively lengthy suites; the music was composed as Carla Bley recovered from an illness. The trio toured with the new music for a while, then retired to the studio where they’ve perfected these pieces. The title piece is a long (clocking in at nearly 24 minutes!), contemplative work of four parts, titled, “Life Goes On,” then “On,” then “And On,” closing with “And Then One Day.” Carla Bley’s piano playing is simply magnificent here, and even though the arrangements are very spare—there’s plenty of room for each of the players to comfortably stretch out. Steve Swallow’s playing alternates constantly between plumbing the depths and plucking at the higher registers of his instrument; he’s definitely one of the most interesting bass players of all time. And British saxophonist Andy Sheppard is one of the finest horn players of this generation; he’s on tenor here, but alternates between tenor and soprano throughout the albums three suites. His tone is quite simply sumptuous and superb here; his runs and fills are deliberate and measured, and he never hurries through his solos—it fits the mood of the piece perfectly. Even at nearly 24 minutes in length, this piece passes waaaay too quickly!

While much of the album is quite subdued and melancholy, this is my favorite jazz recording of 2020 thus far. I did all my listening to the 24/96 stream from Qobuz via Roon—the sound quality was absolutely magnificent streaming across my home system. This record is not to be missed—it comes very highly recommended!

ECM, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, Google Play Music, Deezer)

Carla Bley/Steve Swallow/Andy Sheppard - Life Goes On

Carla Bley has essentially been an active recording artist for sixty years. That’s right—sixty years! Born in 1938 in Oakland, California; her father was a piano teacher and church choirmaster, who taught her at a very young age to play the piano. However, he died when she was only eight years old, and by fourteen, she had decided that being a professional roller skater was her calling. She headed to New York City at seventeen, and took a job as a cigarette girl at legendary jazz club Birdland, where she immediately drew the attention of pianist Paul Bley. Who encouraged her piano playing, and also encouraged her to start composing—within a few years, they were married, and a number of other jazz artists were recording her compositions.

Carla Bley, at age 81, is one of the most prolific jazz composers of all time. I can’t even count the number of studio albums she has to her credit; double that number, and you get the number of albums she’s either collaborated or guested on. Her new album, Life Goes On, features longtime partner and collaborator, bassist Steve Swallow, along with tenor and soprano sax player Andy Sheppard. The trio have been playing together for over twenty-five years; this new record is their fourth album together. To hear the intricate and incredibly nuanced playing on this album, you’d never guess the ages of the players; Steve Swallow is 79, and Andy Sheppard is the youngster of the group at 63!

Life Goes On is a trio of relatively lengthy suites; the music was composed as Carla Bley recovered from an illness. The trio toured with the new music for a while, then retired to the studio where they’ve perfected these pieces. The title piece is a long (clocking in at nearly 24 minutes!), contemplative work of four parts, titled, “Life Goes On,” then “On,” then “And On,” closing with “And Then One Day.” Carla Bley’s piano playing is simply magnificent here, and even though the arrangements are very spare—there’s plenty of room for each of the players to comfortably stretch out. Steve Swallow’s playing alternates constantly between plumbing the depths and plucking at the higher registers of his instrument; he’s definitely one of the most interesting bass players of all time. And British saxophonist Andy Sheppard is one of the finest horn players of this generation; he’s on tenor here, but alternates between tenor and soprano throughout the albums three suites. His tone is quite simply sumptuous and superb here; his runs and fills are deliberate and measured, and he never hurries through his solos—it fits the mood of the piece perfectly. Even at nearly 24 minutes in length, this piece passes waaaay too quickly!

While much of the album is quite subdued and melancholy, this is my favorite jazz recording of 2020 thus far. I did all my listening to the 24/96 stream from Qobuz via Roon—the sound quality was absolutely magnificent streaming across my home system. This record is not to be missed—it comes very highly recommended!

ECM, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, Google Play Music, Deezer)

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.

Recording session for Concurrence. Photo by Jökull Torfason.