Part One and Part Two of this series appeared in Issue 141 and Issue 142.

I started exploring recordings on labels related to the Decca Record Company of England in Issue 141, having discussed several LPs from Lyrita Recorded Edition. Lyrita was an independent label that contracted out the technical aspect of making recordings to Decca, with the owner astutely insisting to have the celebrated recording engineer Kenneth Wilkinson put in charge of the projects whenever possible. This article will explore recordings from Argo and L’Oiseau-Lyre, two labels wholly owned by Decca.

Audiophile recording as we know it started with the English recording engineer Arthur Haddy, whose career began at Western Electric (where pretty much anything to do with high-fidelity audio originated). He was poached by Crystalate, an early record label, where he was later joined by Kenneth Wilkinson. Decca soon took over the company, including the technical team. When World War II started, the Decca engineers were tasked by the British government with developing equipment to detect and record German submarines. Their wartime research not only helped Britain win the war, but also kickstarted the concept of high-fidelity sound with the development of the Full Frequency Range Recording (FFRR) technology. FFRR made possible for the first time the recording of the full spectrum of frequencies perceived by the human ear. Decca can therefore be regarded as the first audiophile record label, with excellent sound quality as one of its stated goals.

When the stereo era arrived, Decca was the first company in Europe, and second in the world (RCA beat Decca to it by two months), to start making stereo recordings. Wilkinson, Haddy and their younger colleague Roy Wallace together developed the famous “Decca Tree” microphone recording technique. The early years of stereo from the mid 1950s to the early 1960s was a period of experimentation, with the engineers setting up different microphone arrangements simultaneously during recording sessions to determine the optimum placement for each recording location (venue). The excellent sound quality of these recordings did not happen by chance; it took meticulous experimentation, a thorough understanding of the acoustics of the recording venues, as well as familiarity with the sound of the orchestras and conductors. Wilkinson is best known for his recordings at Kingsway Hall, a Methodist church hall that was demolished in 1998, and Walthamstow Town Hall. Pretty much any recording made by him in these halls is a guarantee of good sound.

Wilkinson was in charge of training all the younger engineers at Decca until his retirement in 1980. This ensured a consistency of sound quality. Record collectors also pay great heed to the actual label of the LPs, since this represents the era when the record was made. There is a good summary of Decca labelography here: http://milestomozart.blogspot.com/2014/02/lp-week-with-aql-special-report-decca.html

In general, up until the early 1960s, the recording and mastering chains were vacuum tube-based. Gradually, more solid-state equipment was introduced, but this was never clearly stated on the records. One has to assume that by the mid 1970s, most if not all the equipment was solid state. Reissues after the early 1960s of earlier recordings were most likely mastered with solid state equipment and sound different from the original releases. In general, tube-based LPs have a warmer mid-range and the ambience has more bloom. The string tone is ravishingly beautiful. The bass, however, is more bloated. The solid-state LPs have a tighter bottom end, a bit more clarity and more precise imaging. Even though the earlier tube-based cutter head amps were likely less powerful than the later solid-state units, the early stereo LPs are astonishingly dynamic. Early acetate-backed recording tapes have more hiss, while Dolby-encoded tapes from the mid-1970s onwards involved an extra stage of electronics, which could offend one’s audiophile sensibilities. One also has to take into account the improvement in cutter heads as time went on. Therefore, preference for earlier or later labels is entirely down to personal taste.

In this article, I will discuss several LPs that are of demonstration quality, but are not well-known and therefore not in high demand. None of them has been reissued by the modern audiophile labels.

William Mathias – Dance Overture/Ave Rex – A Carol Sequence/Invocation And Dance/Harp Concerto. London Symphony Orchestra, Atherton. L’Oiseau-Lyre SOL346/Decca SXL6607 (1973)

L’Oiseau-Lyre was a Decca label that specialized in early music, but somehow this LP of modern compositions was released in 1973 under this label as well as the usual Decca label. William Mathias (1934 – 1992) was a Welsh composer and music professor who left a large body of choral works, as well as orchestral and organ compositions. The real gem here is the harp concerto. The music is modern but melodious. The first movement is one long flowing line of woodwinds accompanying the harp, with the backing of the strings, percussion and brass. It gives me a feeling of flying through the air over green fields, forests and streams. In the second movement, the mood changes completely. It is darker, as if night has fallen, giving the listener a sense of mystery and foreboding. It has an almost cinematic quality. The final movement returns to a more lighthearted, joyous mood.

The Dance Overture is also a very enjoyable piece of music. It is lighthearted and rhythmic. The style reminds me of some of Malcolm Arnold’s overtures.

The sound is of demonstration quality. The recording was engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson at Kingsway Hall, and it has the Kingsway hallmarks of clarity, great imaging, an all-enveloping soundstage, and superb dynamics. The harp is a good test of transient response, and when well reproduced, sounds as if one is listening to the real thing. The composition also makes good use of other percussive as well as wind instruments, which have a very immediate sound. It belongs in the top rank of Decca recordings. You should be able to find a good copy for less than $20.

Gerhard, Symphony No 4/Violin Concerto. BBC Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis, Yfrah Neaman (Violin). Argo ZRG701 (1972)

Roberto Gerhard was a Catalonian composer and a student of Schoenberg, and escaped the Spanish Civil War to live in England just before the start of the Second World War. His violin concerto is the earlier work on this record, written during World War II. I find the work mesmerizing, with echoes of Prokofiev’s violin concertos. The violin tone is very natural, and there is good balance between the soloist and the orchestra.

Gerhard’s Symphony No. 4 was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, and premiered under the baton of William Steinberg in 1967. It has less of the lyrical qualities of the violin concerto, instead sounding intense and urgent at times, interleaved with moments of contemplation. It makes use of a variety of percussive instruments and stunning passages of virtuoso wind playing.

The recording was made in Hammersmith Town Hall, and the recording team was uncredited. It is no less brilliant than the other Gerhard recording listed here, sharing the same characteristics of explosive dynamics, huge soundstage, tonal naturalness and the illusion of being alive.

Rawsthorne, Symphony No. 3/Gerhard, Concerto For Orchestra. BBC Symphony Orchestra, Norman Del Mar. Argo ZRG553 (1968)

Readers are probably more familiar with Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, one of the most important 20th century compositions. Gerhard’s version has a single movement, and was premiered by Antal Doráti and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the leading American orchestra of the time. The music is atonal, and makes liberal use of percussion, brass and plucked strings. There are some experimental elements, and the recording offers a rich and complex soundscape. There are rapid shifts in dynamics and tempo, presenting formidable challenges to the players. The whole piece is highly atmospheric, and a great showcase for an audiophile recording.

The Rawsthorne Symphony No. 3 is a more conventional composition with four movements. It has some hauntingly beautiful moments, and passages of intensity and dynamic contrasts.

This recording was engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson at Kingsway Hall. It is again a spectacular recording that sounds very natural and alive. The dynamics are breathtaking.

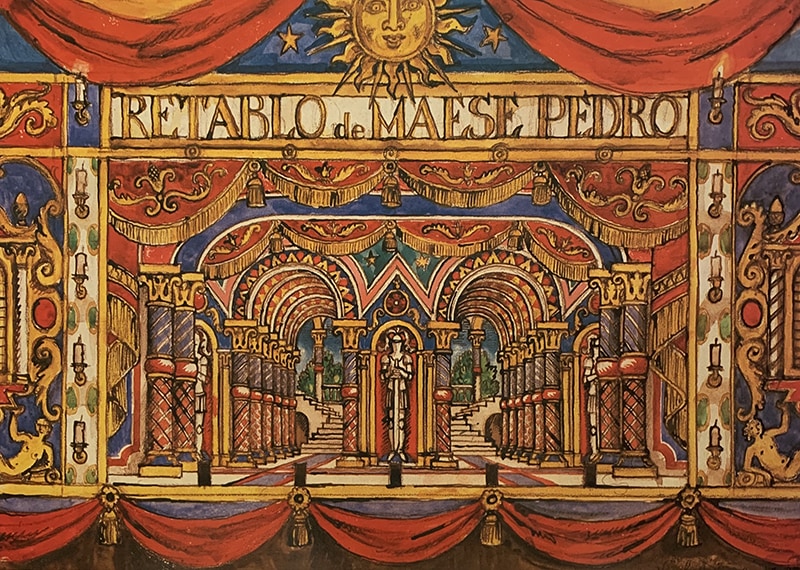

Manuel De Falla – El Retablo De Maese Pedro/Psyche/Harpsichord Concerto. The London Sinfonietta, Simon Rattle, John Constable (Harpsichord). Argo ZRG921 (1981)

The title of the first piece translates as “Master Peter’s Puppet Show,” and is a musical tableau with a soprano, tenor and baritone. It is meant to be an opera based on Cervantes’ Don Quixote, but with puppets instead of actors. The music is fun, with brilliant sound effects using percussive instruments. Recording opera is a particular strength of Decca, with their recording of Solti’s Wagner Ring cycle being regarded by many as the best music recording ever. This recording presents a realistic soundstage with excellent presence of the voices. The dynamics are impressive, and the sound is very transparent and natural. You can close your eyes and see the puppets in front of you.

Psyche is an impressionistic miniature with soprano voice. The voice has a warmth and presence that suits the music well.

The harpsichord concerto is an important work for the composer. Falla was encouraged by the leading harpsichordist of the time, Wanda Landowska, who was involved in the premier performance of El Retablo, to write a piece for harpsichord. Most harpsichord music was written during the Baroque period, and this composition has a totally different style. The balance between the harpsichord and the chamber orchestra is ideal, and the solo instrument again has that “alive” quality that can be quite startling.

Decca recorded the El Retablo and the harpsichord concerto with the great Spanish conductor Ataulfo Argenta back in 1957. I do not have that recording for comparison. This newer recording by the (then) up and coming Simon Rattle should certainly be categorized as one of the great Decca recordings in its own terms.