Here’s a question that should be a softball: who was Europe’s single most influential musician in the early 19th century?

Was it Beethoven? After all, we had hoped to celebrate the 250th anniversary of his birth with interplanetary zeal, including copious performances, new recordings, etc. etc.

But what if I told you that Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792–1868) was that “single most influential musician”? At the very least, he gave Ludwig Van stiff competition back in the day, succeeding in the one genre Beethoven never conquered.

Rossini, an Italian born in Pesaro, wrote 39 operas – the first of them when he was 18 – and then exited the opera scene before he was 40. We know he was tired; perhaps he was also bored. And he could see a big musical shift coming – the dawn of Romanticism – that would require him to work a whole lot harder (more about that below). Rossini’s operas had been enormously successful everywhere, imitated but never surpassed, at least in the public’s eyes. And he was rich.

When Beethoven died in 1827, he was not rich. His influence on younger composers had also waned, partly the result of fallout from the experimental chamber music he wrote during his Late Period. Those works, mainly piano sonatas and string quartets, were neither understood nor appreciated at the time. Beethoven’s reputation among musicians would grow in later years: Robert Schumann, a talented younger composer and journalist, belonged to an emerging generation that did appreciate their forebears, including Bach and Beethoven. And he made no effort to hide his contempt for Pesaro’s bel canto master:

Near the end of the year 1833 there met in Leipzig . . . a number of musicians, chiefly younger men, primarily for social companionship [but] not less for an exchange of ideas about the art which was for them the meat and drink of life – music. It cannot be said that musical conditions in Germany were particularly encouraging at the time. On the stage Rossini still ruled, at the piano Herz and Hünten. And yet only a few years had elapsed since Beethoven, Weber, and Schubert had lived among us. [from Davidsbündlerblätter, 1854]

There are many ways to measure the talent or significance of a composer. For music lovers, initial impressions do matter. If your first taste of Classic opera buffa came via Mozart in, say, Le nozze di Figaro or Così fan tutte, you may experience your first Rossini opera with mingled delight and disappointment. Yes, the vocal fireworks can be stunning – they fizz like prosecco, if not champagne. But heard in sequence, some elements may strike you sometimes as formulaic, uneven in quality, or overly inclined to run a good joke into the ground.

Consider Act One of Il barbiere di Siviglia. This paradigm of Rossinian style is easily his most-often produced opera. Beethoven liked it; so did Verdi. As music, it breaks down into a succession of “numbers,” e.g., arias, duets, trios, or larger ensemble pieces in so-called closed forms – distinctive structures that include a beginning and an ending. Fun fact: they’re called “numbers” because in the score, each is assigned a different number in ascending sequence; see below.

Timings for the opera’s first ten numbers are also given below; my remarks follow the numbered list. Before you read what I have to say, why not watch some of Il barbiere? If you get restless you can skip ahead to the next number (or over a number entirely), then compare your reactions with mine. These ten numbers are preceded by an Overture.

-

- Introduction (8:02): “Piano, pianissimo” (Numbers are typically introduced and/or interrupted with recitative, quick speech-like singing.)

- Cavatina/cabaletta (11:00): “Ecco ridente in cielo” (Almaviva)

- Continuation and stretta of Introduction: “Ehi, Fiorello!”

- [Cabaletta] (18:19): “Largo al factotum” (Figaro)

- Canzone [cavatina] (29:47): “Se il mio nome” (Almaviva)

- Recit./Duet (33:20): “Oh cielo!/Nella stanza/All’ idea di quel metallo” (Figaro, Almaviva)

- Cavatina/Cabaletta (41:36): “Una voce poco fa/Io sono docile” (Rosina)

- Aria (52:14): “La calunnia” (Basilio)

- Duet ((1:00:02): “Dunque io son” (Rosina, Figaro)

- Aria (1:06:37): “A un dottor della mia sorte” (Bartolo)

Which takes us well into Act II, ending with a riotous stretta featuring all five principals, the housemaid, and a chorus of soldiers. My thoughts:

The orchestra’s overture calls the audience to attention and provides characteristic musical energy for what’s to come. These days, directors often stage the overture, providing pantomime or dance accompaniment to the music. Sometimes that works, sometimes it doesn’t. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s film version of La Cenerentola (a Rossini-ized retelling of “Cinderella”) makes a sly statement about Rossini’s basic style by filming its overture in the vast, empty interior of La Scala, a succession of gleaming surfaces bereft of actual human presence:

(1, 2) How to get the actual drama underway? Always tricky. Here we meet Almaviva paying a troupe of musicians to accompany his serenade to Rosina, a young woman he saw in the streets of Madrid. Note the lyrical quality of Almaviva’s tenor voice. His music requires almost as much agility, grace, and speed as anything written for the women. As the 19th century progressed, such “Rossini tenors” were eclipsed by singers capable of louder, more heroic utterances. The category of Lovesick Youth was more likely to be consigned to mezzo-sopranos as a trouser role.

(4) Here’s the aria made famous by Bugs Bunny and others. Quick-witted Figaro, a barber and all-round entrepreneur, introduces himself as the guy who can make it happen, whatever “it” turns out to be. This is a patter song: lots of repeated, rapidly articulated wordplay plus occasional shout-outs to extremely high or low notes. Note that he’s playing directly to the audience here, ignoring the fourth wall. He has yet to encounter his newest client, Almaviva, who, like Figaro, is new in Seville.

(5) Figaro convinces Almaviva to try serenading Rosina again, making two of the first five numbers cavatinas for the principal tenor. Neither song advances the plot, but it’s early enough in the evening that we don’t feel seriously held up.

(6) Figaro and Almaviva negotiate a business relationship. This duet calls for real acting skill and a clever stage director: we have a chance to gain insight into these two young men and their partnership. The music doesn’t spell much of that out, but some creative stage interplay here between master and servant could suggest mutual understanding and a shared spirit of adventure; otherwise this Ode to Filthy Lucre may fall flat. (I think Luigi Alva and Hermann Prey do a pretty good job with it.)

(7) At last, the prima donna sings! We’ve gotten tantalizing glimpses of her at the balcony, but this is her first opportunity to present herself freely and at length. (Since, like Figaro, she’s ignoring the fourth wall, we can safely assume she’s not dissembling.) Her dreamy teenage enthusiasm momentarily gives way to rapid patter as she schemes to overcome her keepers, and she finishes the cavatina with “lo giurai, la vincerò!” (“I swear, I’ll win it!”) The ensuing cabaletta is all about her willful, wily ways. Aside from being a vocal showpiece, the aria should make us fully aware that this character is smart and determined. Almaviva and Figaro should be grateful she’s on their side.

(8, 10) Two of the last three numbers are patter songs for two buffo bassi, the comic bass singers essential to any opera buffa. Rossini’s audiences were apparently addicted to watching grown men issue torrents of sibilant syllables, as in these numbers; I can’t say it sets my heart aflame. “La calunnia” is often cited as an example of Rossini’s ability to orchestrate a continuous crescendo that, like a raging flood, eventually consumes everything in its path. We’re talking about a purely orchestral effect, one easily detached from emotional signifiers: here it represents the toxic power of gossip. If the singer is going to express any personal investment (like fiendishly evil delight!), he’ll have to compete with the orchestra for attention. I’m glad that, thirty years earlier, Mozart made his Basilio a comic tenor. Having two buffo bassi plus Figaro in the same opera strikes me as overkill.

If you made it all the way to that “riotous stretta” forming the finale of Act II, you may have been bowled over by its shift from silly subterfuge into utter madness. Well, that’s what an ensemble finale ought to do! On the other hand, perhaps your willing suspension of disbelief got momentarily un-suspended, because of the way the stage was suddenly filled with loud, passionate strangers. It’s not as well integrated with immediately preceding story elements as in, say, a Mozart comedy. We can’t scold Rossini for not being Mozart, but moments like this do reveal just how paper-thin the artifice can get. (Pie-throwing is more fun when the tossing of pastries seems organically motivated.)

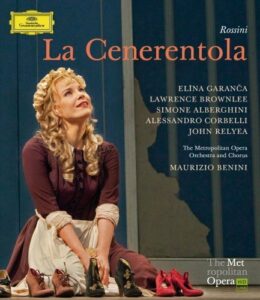

Recommendations: beyond Ponnelle’s film, there are some very fine performances on record (consider those conducted by Galliera, Humburg, Abbado, and Marriner here) and DVD, not to mention Met Opera on Demand. La Cenerentola is another Rossini comedy you might enjoy. Ponnelle’s film, above, features Frederica von Stade in one of her finest roles. I also like Garanča in the 2009 Met production, available both in Blu-ray and online, and the 2005 Glyndebourne production with Ruxandra Donose.

Throughout his lifetime, Rossini also turned out extremely successful opera seria. In the past thirty years his serious operas have regained respect, and not just from aficionados; I really should end this column by recommending one. But there’s no way to do justice to that Rossini, a proper tragedian and budding Romantic, in one or two sentences. It’ll take a whole ‘nother column.

In the meantime, I can recommend a couple of Greatest Hits albums. A superlative new Rossini collection, Amici e Rivali, from tenors Lawrence Brownlee and Michael Spyres, includes gorgeous, technically astonishing duets and other ensembles from Otello, La donna del lago, and, yes, Il barbiere. Here’s a sneak peek:

In TMT’s December 28 end-of-year “awards” column, I’ll also heap praise on a Rossini aria collection from mezzo-soprano Karine Deshayes. Hope you’ll check that out.