Let’s cut straight to the chase: Who won the loudness wars?

Nobody.

(For the benefit of those unfamiliar with the term, the “Loudness War” refers to the practice of trying to make a recording sound as loud as possible and, as Wikipedia notes, “the trend of increasing audio levels in recorded music.”) The listeners are not getting better sound. The record labels are not making more money. The recording and mastering engineers are not demonstrating the best of their abilities. The artists are not being represented at their finest. So why are we still in the trenches?

Largely because jazz bands feel insecure if their album is not as loud as the latest Metallica album (true story). Record labels feel insecure if their releases are not as loud as those of other record labels and mastering engineers feel insecure about working towards what best serves the music, in case someone else who just makes it louder ends up getting all the customers. But how did we get to this point?

Well, once upon a time, electricity was a rare luxury and gramophones were hand-cranked. Acoustic sound reproduction did not offer any convenient means of adjusting the level of the reproduced sound, so under these circumstances, a louder record would indeed play back louder. This effect carried on into the electrical era with the jukebox.

The idea, which to a certain extent was quite true, was that the louder record would stand out and as such, would be noticed more. Sort of like the stranger walking into the saloon, the pianist stops playing, everybody stops talking and, well, the stranger gets noticed (and subsequently gets shot full of 45-caliber holes, unless the stranger can draw and shoot faster than his shadow, in which case only the pianist survives).

In the electrical era, bars no longer had pianists but had jukeboxes instead, where the level would be set once and would remain at that same setting for all records to be played back. The assumption was that the louder record would be noticed and everyone would rush to the stores to buy it. Whether this assumption had any bearing in reality or not is largely irrelevant now, since for many decades, the means for adjusting the playback level as required have been in universal use and are often even automated.

A prime example is radio broadcasting. In the early days, a DJ would manually set the playback level. But it wasn’t long before the FCC (the Federal Communications Commission in the United States and equivalents in other countries) became quite strict about overmodulated broadcasts (too loud and causing the transmitter to produce harmonics at other frequencies) but the market (advertising revenue) at the other end was pushing for the widest coverage possible, which meant broadcasting as loud as possible without the FCC fining the station. The technical solution arrived in the form of automated signal conditioners, devices which would push the average signal level up while also imposing a strict ceiling to prevent overmodulation. It no longer mattered much if a record was louder, as they would all end up equally loud. In fact, overly loud records started to sound awful on air, as all the automated signal processors could do was to clip the signal to prevent overmodulation.

In bars and nightclubs, DJ’s would still manually level-match the records to maintain uniformity during their set, but they are now often assisted by devices similar to those used in the broadcasting sector.

Online streaming services are also implementing automatic level-matching algorithms, which are the software equivalent to the hardware used in broadcasting.

Home listeners, on the other hand, are free to set the volume control to taste. If a record is louder, they are likely to turn it down a bit. If the next one is less loud, it can be promptly turned up again. The latest trends in home listening systems include, in addition to the traditional volume control, level-matching functions.

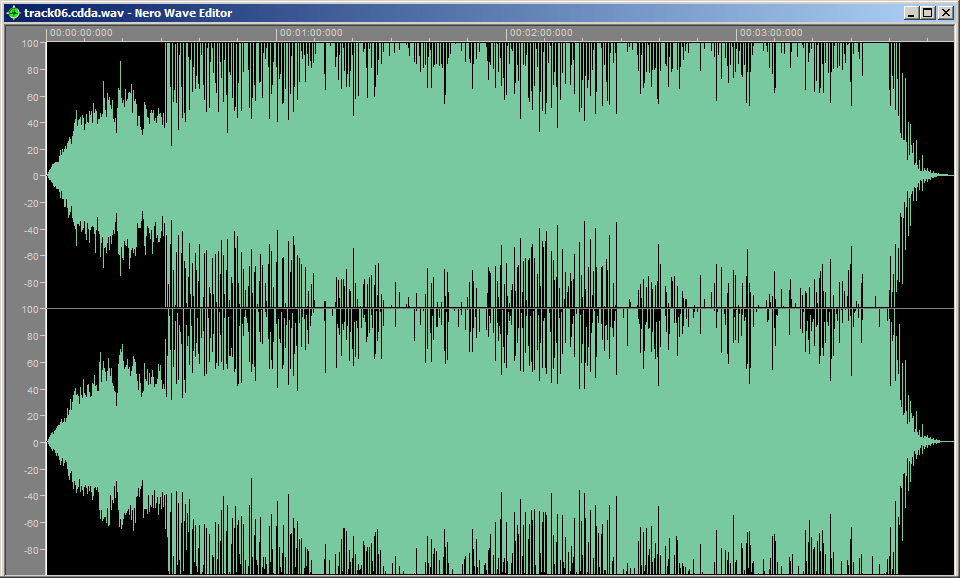

Back in the day when the vinyl record was the main consumer format, things were not yet as bad, since that medium does not have a strict upper level limit. But then came the CD and with it, digital audio. Nothing is allowed to exceed 0 dBFS, but the loudness wars resulted in nothing being tolerated to fall much below -3 dBFS in modern pop music either. This leaves us with a dynamic range of 3 dB…in other words, no dynamics. They have been sacrificed for the sake of higher average (apparent) loudness. It doesn’t sound better, just louder. There are even commercially released CDs with a dynamic range of just a fraction of a dB!

Up to a certain point in time, recordings would still be done in a reasonable manner and the loudness slamming would occur later, at the mastering stage. But by now, it has become more and more common to see recordings already mercilessly compressed before they even get to mastering. This cannot be undone, so the mastering engineer’s hands are tied when dealing with such recordings.

To make matters worse and to keep costs down, it is common practice nowadays to have the lacquer master disks for vinyl record manufacturing cut from the same slammed digital files that were prepared for the CD release! The two formats are very different in many ways and this only serves to ensure that the vinyl record will sound just as bad, if not worse, than the CD.

For many decades now, there has been absolutely no valid technical justification for sacrificing the dynamics and overall sound quality of an album just to make it louder. Yet, this is exactly what many marketing departments are still pushing for. What digital audio brought to all of this, along with the 0 dBFS ceiling, was a general de-professionalization of the industry. The complex and remarkably expensive electromechanical sound recording devices of the past really did require properly qualified engineers to operate them, or expensive damage would result. Modern digital audio workstations (DAWs), on the other hand, have opened up the industry to less technically-minded individuals and the recording process is now largely seen as an art, free of any technical constraints, rather than as a science.

The truth is that it has always involved both art and science. Even nowadays, you cannot take the science out of it. Granted, the DAW probably won’t break and even if it did, it is not that expensive, compared to what a disk recording lathe, a tape machine, or a good analog mixing console used to cost back in the day. But it is just as easy to make a DAW sound dreadful. The difference is that in the DAW era, it has become far more socially acceptable to produce dreadful recordings.

It is no coincidence that the worst of the loudness wars has occurred in the digital era, when it would least be needed.

Let us not forget that Claude Shannon’s seminal 1949 paper, introducing the idea of digital sampling and the subsequent reconstruction of analog signals, was titled “Communication in the Presence of Noise.” The big strength of digital audio is the remarkable ease with which a low noise floor can be achieved. This can be used to great advantage in achieving a good dynamic range in a recording, but is rarely encountered in practice due to the loudness wars.

It was not easy to maintain a very low noise floor when working with magnetic tape and grooved media, but the professionals at the time were using all the skill at their disposal to use the available tools to their full potential. Not everyone could do it well. Digital made it possible for even a beginner to be able to routinely achieve a very respectable dynamic range, but this is more often than not intentionally thrown away for the sake of “competitive loudness.”

A solid understanding of the engineering and science behind what we are doing is essential to avoid making the wrong assumptions, often made by those who are not even involved with audio, but who hold on to outdated marketing ideas of the gramophone era. Not to mention that back then there was still plenty of room to go louder without compromise. Going louder at that point in history actually improved the dynamic range, and the technology was still evolving. But we are now long past the point where the dynamic range started falling again, collapsing to lows that would have never been deemed acceptable in the gramophone era!

Really, how many of you listen to music on systems that do not offer any means of adjusting the level (a volume control)? How many of you would choose to buy an album that does not actually sound good, but appears louder than the albums in your collection that do sound good? These are two of the fundamentally flawed assumptions that the loudness wars are based on. It is about time our industry rediscovers the level of professionalism it had during its golden age, when the good engineers still worked in audio (rather than in defense and aerospace, and of course there are exceptions) and excellent recordings were not all that rare.

Just imagine a conductor of a world-class orchestra deciding that Beethoven’s 9th Symphony should be performed in fortissississimo throughout, from start to finish, in the assumption that it would attract a bigger audience (which it probably would, to witness the sheer absurdity of such a proposition). Now imagine if the majority of conductors the world over decided to do the same with all orchestral works because they feel insecure, and classical musicians only receive training in fortissississimo playing because both they and their teachers feel too insecure…

OK, I’ll stop here before I give anyone ideas that would prove detrimental to the health and safety of the brass section!

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Damian Yerrick.