Way before Menudo there was Rhinoceros.

Rhinoceros was a late 1960s rock band and the brainchild of Elektra Records’ producers Paul Rothchild and Frazier Mohawk (aka Barry Friedman). Mohawk had approached Rothchild with a vision of building a “supergroup,” relying on an elaborate audition process conducted with musicians across North America.

The creation of Rhinoceros is antithetical to how rock groups traditionally are created. Most bands are formed organically with musicians coming together based on shared musical interests. Of course, it’s not uncommon for established bands to audition a new bass player or drummer (say it ain’t so, Pete Best), but it was highly unusual even back then to audition and assemble a band from scratch based solely on a third party’s vision.

In essence, Rhinoceros was an arranged marriage of musicians, with Paul Rothchild functioning as both producer and matchmaker. (You can add the Monkees and The Partridge Family to the mix of “manufactured bands,” though those pop groups were created primarily for television.)

Rothchild and Mohawk (both now deceased) initially invited 12 musicians to audition at Mohawk’s Laurel Canyon home, followed by a second audition where an additional twenty musicians showcased their chops. In the 1960s, Los Angeles’s Laurel Canyon was quite communal and full of aspiring musicians, ultimately spawning the likes of David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne. Fame and fortune, however, was only realized by a select few.

Rothchild and Mohawk’s quest to find the right mix of talent for their preordained “supergroup” (with apologies to Blind Faith, Crosby, Stills, & Nash, Bad Company, Emerson Lake and Palmer, etc.) continued for months and expanded to several cities. While a prospect’s musical talent was obviously the most important criterion, intangibles such as band chemistry were seemingly minimized or lacking in consideration.

Elektra Records was the perfect label for this sort of lab experiment. Elektra was founded by Jac Holzman, a visionary who started the label at 19 from his college dorm room with $300. By the late 1960s, Elektra had amassed an eclectic roster of artists, including The Doors, Love, The Stooges, MC5, Tim Buckley and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band among others.

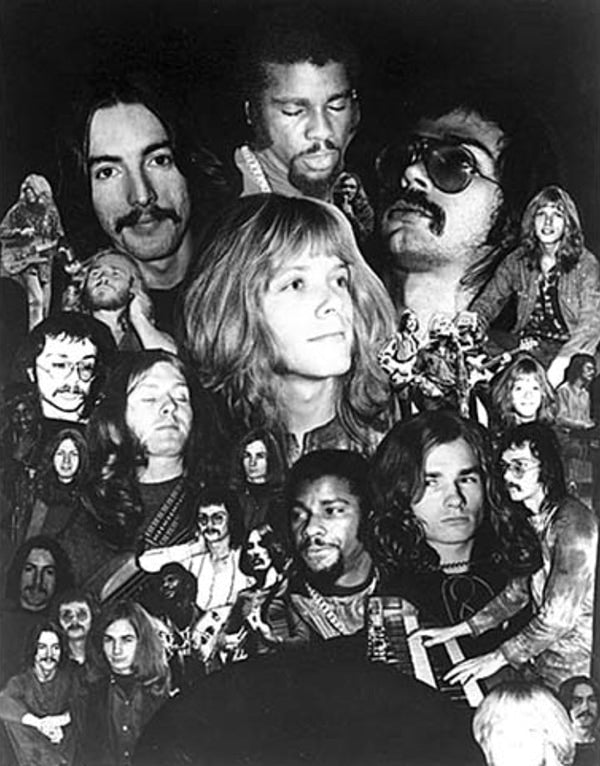

Rhinoceros album cover.

Holzman also underwrote an experimental music project at the Paxton Lodge in northern California. The goal of the project, conceived by Frazier Mohawk, was to provide a creative environment for music making. Artists would take up residency at the lodge with Elektra underwriting all expenses, including building a recording studio, and providing sound engineers, chefs, meals, housekeeping and so on. An early lodge resident included a young Jackson Browne.

The Paxton Lodge project did not have a particularly auspicious beginning. Before renovations to the lodge were complete, various friends, girlfriends, groupies and other assorted characters started showing up. The lodge quickly became known for its drugs, partying and communal debauchery. Reflecting on the failed Paxton Lodge experiment, Browne said this, “it was like bringing dance hall girls to the miners.”

Once Rothschild-Mohawk finalized Rhinoceros’s auditions, an in-studio band was put together consisting of John Finley (vocals), Alan Gerber (vocals, piano), Danny Weiss (lead guitar, piano), Danny Hastings (guitar), Michael Fonfara (organ), Jerry Penrod (bass) and Billy Mundi (drums).

Danny Hastings had spent time with Buffalo Springfield, Danny Weiss and Jerry Penrod with Iron Butterfly, and John Finley and Michael Fonfara with a prominent Canadian R&B band named Jon and Lee & the Checkmates. Drummer Billy Mundi by far had the most eclectic background. A one-time member of Hells Angels, Mundi also played with the Mothers of Invention and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, presumably not at the same time.

Here’s how lead singer John Finley described his Rhinoceros audition at the time: “It was scary as hell. It was like football tryouts, a cattle call. There were people from the West Coast, people from Chicago, Omaha, people from all over the place. I was totally intimidated. Everybody was a songwriter and I’m not a songwriter. I had written a little, but I was a singer. All I could do was go to the piano and sing the blues.”

Elektra Records paid each Rhinoceros band member a salary during the rehearsal and recording periods, an unheard of arrangement for that era. It’s estimated Elektra’s upfront investment in the band was as much as $80,000, a considerable sum for a bunch of relatively unknown 1960s musicians.

There was an enormous PR buzz leading up to the band’s self-titled release (Rhinoceros, 1968). Producer Paul Rothchild’s publicly stated goal of creating a “supergroup” made it extremely challenging for Rhinoceros to live up to the hype and expectations. Elektra also contributed to the pre-release hype by purchasing large billboards on LA’s Sunset Boulevard, and running ads in the leading music trade pubs showcasing the band and the album’s exquisite cover art.

The debut LP’s gatefold cover depicts a colorful, beaded mosaic of a rhinoceros created by Gene Szafran, an artist who years later sadly developed multiple sclerosis, severely curtailing his artistic pursuits. The Rhinoceros cover received a Grammy nomination for best album cover of the year. The cover generated so much notoriety, it led to the creation and sale of high-quality, limited-edition prints signed by Szafran.

Paul Rothchild was both an extraordinary producer (The Doors, Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield Blues Band and others) and a showman. Rhinoceros lead guitarist Danny Weiss said this of Rothchild, “the concept he had was of a supergroup, and at one time the band was even gonna be called Supergroup. Another name he came up with was Mach 7. One day Rothchild got the whole band together, and the name (Mach 7) was up on an easel. He created this big dramatic thing. As he unveiled it, you know, pulled a cloth off the name, the looks on everyone’s faces in the band [were] like completely blank…it was like…’Oh’!’”

Under Rothchild’s tutelage, the debut album was a mix of psychedelic rock and R&B. Alan Gerber and John Finley did most of the songwriting, and the LP featured two singles: “I Don’t Want To Discuss It (You’re My Girl)” and “I Will Serenade You,” later covered by Three Dog Night in 1973. Interestingly, the lone track from the album that has stood the test of time is the well-known instrumental “Apricot Brandy.”

Unfortunately, despite all the publicity and Rothchild’s careful crafting and planning, the band’s debut album sold poorly. By the time their second album Satin Chickens (1969) was recorded, there were already band departures, and neither Rothchild nor Mohawk were involved in its production. The band’s third and last album, Better Times Are Coming, was released in 1970. The album title was meant as a statement about the nation’s divisive state, while hardly being prophetic about the band’s future. Sales on both Rhinoceros’s second and third LP’s also performed poorly.

Rhinoceros, Better Times Are Coming album cover.

Recording engineer John Haeny (The Doors, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt) worked on Rhinoceros’s debut LP. “From my point of view,” said Haeny, “none of the band was ‘super’ in that none were big time established rock musicians. The concept of Rhinoceros was not to go out and steal frontline players from great established bands. It was more a matter of scouring the planet for lesser-known players that had exceptional talent, and put them together with funding by a record company, so they could be given an opportunity to succeed. Of course, everyone had hopes for greatness.”

The first time I saw Rhinoceros live was in 1969 at the New York State Pavilion on the grounds of the former 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, New York. Rhinoceros was part of an eclectic concert bill that included Procol Harum, Spooky Tooth and NRBQ. I remember it was a beautiful summer evening, and collectively it was a really, really good concert.

The next and last time I saw Rhinoceros perform live was in my high school gymnasium, which exemplifies the downward spiral the band experienced in a short two or three-year period. What do I remember from that gymnasium show? Well, they played “Apricot Brandy,” the band’s quasi-hit (Number 46 on the Billboard chart), two times during their short set. I’ve never since heard an artist play the same song twice in a concert performance.

Showman P.T. Barnum is credited with coining the phrase, “all publicity is good publicity.” Rhinoceros’s launch experience sort of belies that fact, though if a band’s music is truly noteworthy, it should be able to overcome any stigma of being over-hyped. I’m probably a bit of an outlier, but I actually like the band’s debut LP.

Not surprisingly, Rhinoceros’s lack of success was a big disappointment to Elektra owner Jac Holzman. As far the musicians were concerned, being part of a band with a major label recording contract was like winning Lotto. Rothchild was the puppet master and the band was more than willing to relinquish any and all creative control to him.

Only in retrospect was there a belief that some of his choices lead to the band’s lack of success. First, there was the ridiculous hype. Second, there was frustration as band members believed some of their best songs were not included in the band’s debut LP, as they didn’t fit either Rothchild’s or Elektra’s vision.

Musicians come together organically because there’s symmetry, a shared vision and a desire to work with one another. The pressure for Rhinoceros to succeed was immense, driven by hype and a flawed developmental strategy. There are also many intangibles that contribute to artist chemistry that go well beyond musicianship. Recording engineer Haeny noted, “The band wasn’t an ideal combination of personalities, and they certainly weren’t each other’s best friends all the time. You just can’t create musical magic out of a business plan.”

Amen to that.

Epilogue: In 2009, most of the original Rhinoceros lineup reunited for a one-time performance at the Kitchener Blues Festival in Ontario, Canada.

Header image: Rhinoceros promo photo