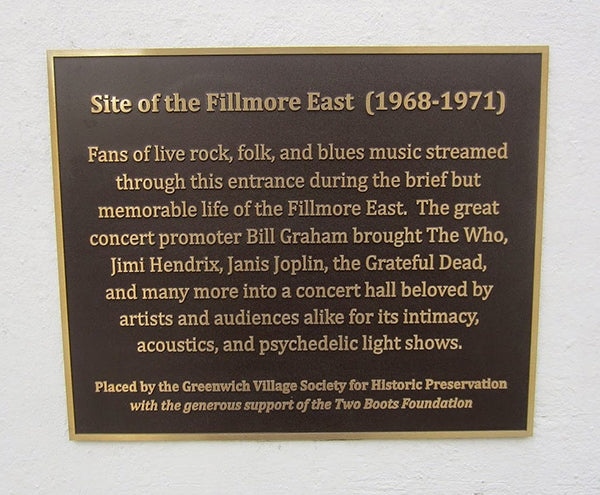

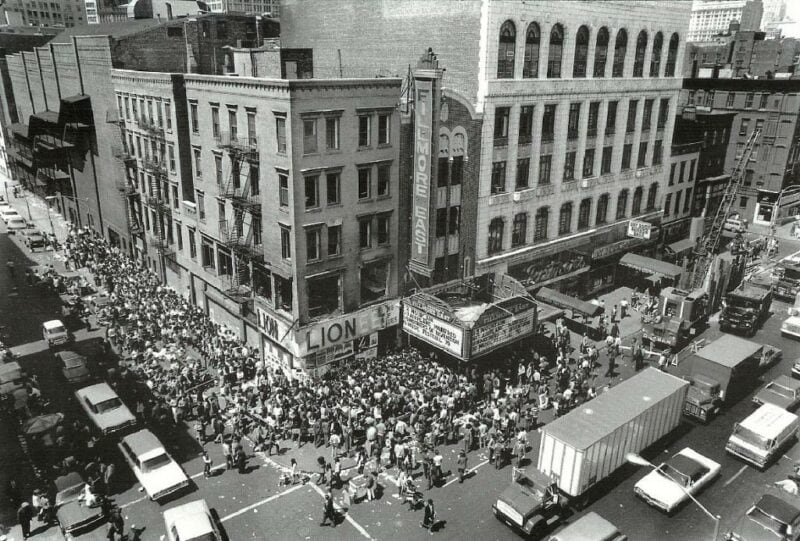

New York’s famed Fillmore East closed 50 years ago this year. It’s hard to believe it was that long ago. Although only operational for a relatively short three-year period (1968 – 1971), the Fillmore East was central to 1960s music, the era’s counterculture movement and its generational ethos. A lot of the music performed at the Fillmore was politically based and socially driven. The 2,654-seat venue provided an atmosphere that was intimate and infectious, with both exceptional acoustics and sound.

Music promoter and impresario Bill Graham, seeking a New York City counterpart to his San Francisco Fillmore West venue, purchased the Greenwich Village Second Avenue theater, previously known for its Yiddish performances, in 1968.

The first performance at the Fillmore East was on March 8, 1968. It was a triple-bill featuring Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, bluesman Albert King, and folk-rock artist Tim Buckley. A three-artist bill was standard fare at the Fillmore, and it also was common for Graham to book artists from different musical genres on the same night. He viewed that booking strategy as a tool for “audience enlightenment.”

Bill Graham was born in Berlin in 1931, and as a child he narrowly escaped the Holocaust. His father tragically died in an accident just two days after his birth, while his mother perished at the hands of the Nazis at Auschwitz. Graham’s life was likely spared when his mother placed him in a French orphanage in a pre-Holocaust exchange of Jewish children for Christian orphans.

At the age of 10, Graham (who died in 1991 at age 60) was placed in an orphanage in the Bronx, New York, and was subsequently adopted by a local family. Graham later attended City College of New York (CCNY) and also served in the Korean War, where he was awarded both a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. In the early ’60s, he migrated to San Francisco and began his career as a music promoter. Graham had a reputation for being surly, difficult and lacking in patience. He had a particular disdain for tardiness.

How good was the sound and performances at the Fillmore East? Well, no less than thirty classic live recordings from the venue have been released.

Some of the most notable albums include, The Allman Brothers At Fillmore East (1971); Crosby, Stills Nash & Young, 4 Way Street (1971); Humble Pie Performance Rockin’ The Fillmore (1971), Joe Cocker, Mad Dogs & Englishmen (1970), Miles Davis at Fillmore (1970), Jimi Hendrix, Band of Gypsy’s (1970), John Mayall, The Turning Point (1969) and Derek and the Dominos Live At The Fillmore (1973).

The Fillmore East.

The Fillmore East.Just that short list of albums alone speaks to the exceptional music that emanated from the hallowed venue, where the best orchestra seats were priced at a relatively modest $5.50.

Of course, accompanying many live Fillmore East performances was the psychedelic Joshua Light Show. Created by Joshua White, the light show used many different image-making devices to add to an artist’s onstage musical performance. The “liquid light show” was showcased behind the artist, and its revolutionary visual effect enhanced the overall concert experience. A Fillmore show was known for both its sight and sound.

In a recently-published book, Fillmore East: The Venue That Changed Rock Music Forever, journalist/photographer Frank Mastropolo interviewed 90 musicians and assorted crew, who share their personal memories about the venue.

Singer/guitarist Steve Miller recalls having to follow show opener Mungo Jerry (“In the Summertime”), who, before departing the stage, distributed 500 kazoos to the Fillmore audience. This now well-equipped army of kazoo enthusiasts then uninvitedly decided to jam along with Steve Miller and his band’s set. Not exactly what Miller had in mind, but he and the band had no choice but to roll with it.

David Clayton-Thomas (vocalist for Blood, Sweat & Tears) humorously recalls guitarist Steve Katz’s mother delivering chicken soup to the band backstage in her then-stylish mink coat, and having to step over all the dopers stretched out in the backstage area.

Doug Clifford (drummer, Creedence Clearwater Revival) recalls a night where the audience demanded an unprecedented 17 encores. Bill Graham commemorated the occasion by giving each band member an inscribed gold watch.

It wasn’t terribly uncommon for some bands to play until the wee hours of the morning. Elvin Bishop (guitarist, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Elvin Bishop Group) had this to say: “you can’t visualize today a big venue letting people jam until four or five in the morning. It’s just so cold-blooded (and all) about the money. Nowadays the venues sell those tickets, they do the show and they get your ass out of there and that’s it.”

The first of many Fillmore East concerts I attended was on October 31, 1969. The headliner was Mountain, a band fronted by the now-deceased Leslie West (guitar, vocals) and Felix Pappalardi (bass, vocals). The other scheduled artists that evening were the Steve Miller Band and The Move, fronted by Jeff Lynne and Roy Wood. The Move disappointedly was a late scratch and was replaced by the Steve Baron Quartet, a contemporary folk group. Keeping with Graham’s mix and match booking strategy, the Quartet was somewhat of an odd complement to the evening’s other performers.

As an impressionable young teen, that first Fillmore concert was a coming of age moment. It wasn’t just the musical experience, which from my sixth-row orchestra seat was magical. It was also about experiencing and gaining a stronger appreciation for the counterculture vibe emanating from the streets of Greenwich Village. The neighborhood was a big part of the 1960s counterculture movement, driven by the news of the day: the Vietnam War, civil rights and the military draft.

The air in the Fillmore East was often thick with the pungent smell of marijuana, and patrons had to exercise a fair amount of discretion when indulging. The Fillmore ushers prowling the aisles would shine a flashlight on those actively lighting up, which was a no-no. It was sort of a hippie version of theater matrons patrolling the aisles at your local movie cinema, though their job was to curtail youthful chatter rather than the use of illicit drugs.

Of course, there also was the heavy use of hallucinogenics, with the audience’s proclivity directly correlated to whatever band was performing. Though never part of any research study, as far as I know, the Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd are two noteworthy artists that likely had a strong correlation. If you were graphing the two variables – bands and audience hallucinogenics – the graph lines for the Dead and Pink Floyd would likely resemble a hockey stick.

I have a vivid memory at one Fillmore concert where the ushers had to wrestle a gentleman off the safety railings in the balcony, fearing he was about to swan dive to the lower orchestra level. Let’s just say, being an usher at the Fillmore was not for the faint of heart.

Arguably the most infamous night at the Fillmore East occurred on May 16, 1969. The headliner that evening was The Who. In the midst of the band’s set, a fire broke out in a building adjacent to the venue. Although the Fillmore was not in immediate danger, as a precaution the New York Fire Department ordered the venue evacuated.

When a plainclothes NYPD officer tried to take control of the stage to make an announcement, the band mistook him for a crazy fan, oblivious to the chaos ensuing around them. The Who’s Pete Townsend instinctively went into attack mode, kicking the officer in his Baba O’Riley’s. Luckily for both the officer and Townsend, his aim was slightly off target. To add insult to injury, the non-uniformed officer was then bounced from the venue by the Fillmore’s security team, who also was oblivious to the fire and evacuation order. Bill Graham then took the stage and informed the crowd about the “fire across the street,” intentionally downplaying its proximity to the venue.

Pete Townshend was subsequently issued a summons for simple assault, though the NYPD desired a felony assault charge for kicking a police officer in the line of duty.

When Graham closed the Fillmore, he blamed it on artist greed and changing industry economics. “Some top rock musicians would rather play a 20,000 seat arena like Madison Square Garden for an hour’s work (and make $50,000), rather than the 2,600‐seat Fillmore East (for four hours and make roughly $20,000).”

It’s hard to argue against arena economics, but the experience at the Fillmore for both artist and audience was far, far superior to any large arena show in terms of acoustics, sound, ambiance and intimacy.

A short walk from the Fillmore East’s Second Avenue and Sixth Street location is St. Marks Place. St. Marks back then consisted of a variety of downtrodden apartments and retail businesses, including seedy bars, head shops, funky clothing stores, record shops and the Electric Circus, a venue that couldn’t be more aptly named.

Artwork from the interior of the Electric Circus. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Keith V. Johnson.

Artwork from the interior of the Electric Circus. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Keith V. Johnson.

The Electric Circus was emblematic of the wild and crazy side of the 1960s. It was a combination nightclub, discotheque and music venue. It featured flame throwing jugglers and trapeze artists who performed between musical performances, as strobe lights flashed over a large dance floor. Lots of eclectic bands played there, including The Velvet Underground. Going to the Electric Circus was a visceral, multimedia experience, featuring music, dance and performance art.

Several of the era’s famous and infamous also resided on St. Marks, including comedian Lenny Bruce and activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. Both Hoffman and Rubin were founding members of the Youth International Party (the “Yippies”), while Hoffman is also known for the counterculture bestseller Steal This Book, which he self-published after no less than 30 publishers refused to print it.

Some other notable 1960s-era Greenwich Village music clubs and coffeehouses included Gerde’s Folk City, The Bitter End, Café Au Go Go, Café Figaro, The Five Spot Café, the Village Vanguard, Café Wha? and The Gaslight Café.

What’s considered a coffeehouse today versus back in the 1960s is resoundingly different. Let’s just say Starbucks wouldn’t exactly pass muster, nor would a patron ordering a triple-venti, half sweet, non-fat, caramel macchiato. A coffeehouse in the ’60s might include both poetry readings and musical performances, quite often of the folk variety. They were gathering places for artists, writers, musicians and poets.

Gerde’s Folk City is well-known for hosting Bob Dylan’s first paid public performance, opening for John Lee Hooker. The venue also helped launch the careers of many other artists, including Peter, Paul

Two noteworthy performances at The Gaslight Café include Joni Mitchell’s first live New York City show and the first electric appearance by The Blues Project.

If the Fillmore East was the mecca of NYC rock during its heyday, then the Village Vanguard is the same, if not more, for jazz music. Opened in 1935, the Village Vanguard is the oldest jazz club in New York. Musicians who’ve performed there are a veritable who’s who of jazz, including Miles, Monk, Mingus, Coltrane, Evans and Tyner, to name a few. It wasn’t always wine and roses, though, at the small 123-seat club. The mercurial Charles Mingus once held a knife to the throat of club owner Max Gordon for an alleged underpayment. Another time, Mingus tore the front door off the club’s hinges when Gordon neglected to add the words “Jazz Workshop” after Mingus’s name.

Café Wha? is probably best-known as the club where bassist Chas Chandler (The Animals) in 1966 discovered Jimi Hendrix, who was playing five sets a night, six days a week as “Jimmy James and the Blue Flames.”

The Bitter End on Bleecker Street, opened in 1961, is a venerable shrine to Greenwich Village entertainment. Initially managed and then owned by the late Paul Colby, The Bitter End helped launch the careers of an endless number of well-known folk artists, comedians, country and rock bands. Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan, Neil Diamond, Curtis Mayfield, Randy Newman and Jackson Browne can all trace their roots back to the venue. Van Morrison kicked over tables while performing, for dramatic effect, while James Taylor is said to have bombed at the club in some of his earliest career performances.

Dick Cavett, George Carlin, Billy Crystal, Joan Rivers and, of course, Lenny Bruce are a few of the comedic luminaries who fine-tuned their craft at the venue. Woody Allen allegedly was so nervous before his very first set at the club that he tried to crawl out a back window.

Yet another Greenwich Village cultural institution was the Hotel Albert, located on 11th Street. What began as three row houses constructed in 1850 was converted first into the St. Stephen hotel in 1875, and with additional expansion, rechristened the Hotel Albert in 1902.

For decades the Hotel Albert served as a meeting place for musicians, artists, writers and political radicals. Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Salvador Dali, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol all resided at the hotel at one time or another. In the years leading up to McCarthyism, the Communist party is also alleged to have held secret meetings at the Albert.

The Hotel Albert is where Paul Butterfield formed his blues band. It’s also where John Sebastian wrote the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Do You Believe In Magic,” The Mamas & The Papa’s created “California Dreamin’” and where Canned Heat jammed with Eric Clapton and Cream. Musicians would rehearse and jam in the hotel’s gritty basement, with water leaks and dancing cockroaches hardly diminishing their desire for music creation. So, what became of the Hotel Albert? Today it’s a complex of 190 co-op apartments.

I’ve barely touched the fringes of the rich history that each of these iconic music and entertainment venues possesses. Most unfortunately are no longer with us, and those that remain are sadly struggling to survive, especially during the COVID-19 era.

There’s no doubt they’ll be new venues to replace the ones that disappear, but the bigger question is whether the collective caliber of music and entertainment that emanates from these new venues can remotely hold a candle to what transpired in Greenwich Village in the 1960s.

It was a special time and a special place.