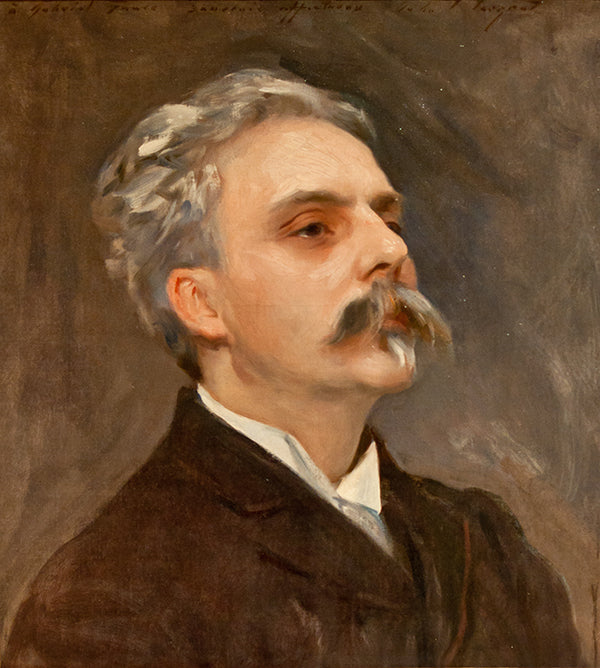

Sometimes all it takes is one outstanding teacher to release a young student’s artistic gifts. French composer Gabriel Fauré (1845 – 1924) found such a mentor in Camille Saint-Saëns at the music-focused boarding school that Fauré attended for 11 years in Paris. The result was not only a decades-long friendship, but also a compositional career so esteemed that, at the end of Fauré’s life, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, an award not usually given to a musician.

Fauré is probably best known today for his heart-on-sleeve orchestral pieces like the Pavane and the Requiem. However, it’s his chamber works that have been getting the most attention lately in the recording industry.

Among Fauré’s more intimate creations are a significant number of songs for voice and piano. Some, like “Claire de lune,” are commonly performed. But, until tenor Cyrille Dubois’s new release on the Aparté label, there had never been a complete recording of Fauré’s songs. Dubois is joined by his usual performing partner, pianist Tristan Raës. Even casual fans of French art song (or mélodies, as they were called in those days) will recognize famous gems such as the languid “Après un rêve,” Op. 7 No. 1:

Fauré wrote over a hundred mélodies, offered here on three disks. Because some were not composed for tenor, and a few were intended as vocal duets, Dubois and Raës undertook a bit of creative rewriting to allow them to perform all the songs. Those changes are not intrusive – perhaps they would be to a hardcore Fauré fanatic – and the duo has a pleasingly fluid style.

As Dubois explains in the booklet, they decided to organize the songs into three mixed recitals rather than chronologically. Given Fauré’s development as a composer throughout his long career, especially in terms of his more experimental late output when he was going deaf, it would have been fascinating to hear them in the order they were composed. Fortunately, the date for each song is provided, making comparison easier. Here, for example, is “C’est la paix,” a late work from 1919, only five years before the composer’s death, in quite a different style from the early “Après un rêve.”

Somehow Dubois also found time to participate in another Fauré recording project, this one on the Klarthe label. Fauré le dramaturge focuses on music he composed for theatrical settings, particularly incidental music for plays. These pieces would have been performed by a small chamber orchestra, as they are here by Ensemble Musica Nigella, under the direction of Takénori Némoto.

The track list is mostly instrumental music, including the famed Pavane in its orchestral version, which has a gossamer clarity when played by a small group instead of a symphony orchestra. Along with Dubois, soprano Cécile Achille is on hand to provide the few needed vocals. Her sound is light as air in the beautiful “Mélisande’s Song,” one of several selections Fauré wrote for a British production of the Maurice Maeterlinck play Pelleas and Mélisande. The play had been translated from French, and so the song is in English.

The Ensemble Musica Nigella frequently suffers from intonation problems, especially unfortunate given the rare, even unique, nature of some of the repertoire on the album; it’s not as if you can easily find another recording. There is one piece – the texturally and harmonically daring movements for a 1901 play called Le voile du bonheur – that has never been published.

Another little-known highlight is Fauré’s incidental music for Shylock, playwright Edmond Haraucourt’s 1889 adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Conductor Némoto took on the task of “reconstructing” the composer’s original version for chamber orchestra, presumably lost.

Dubois sings a chanson as part of the Shylock movements. His delivery is, as always, like a river in springtime, flowing and sparkling. His presence even seems to improve the orchestra’s playing.

Fauré wrote a lot of instrumental chamber music with no connection to the theater. The 2022 album Horizons II, on Aparté, completes a two-part series of chamber-music recordings started in 2018. Two groups participated: a string quartet called Quatuor Strada and a nameless piano quartet (piano, violin, viola, cello) that shares its violinist with the string quartet.

Because he did not begin concentrating on chamber music until middle age, Fauré’s output in this genre is more intense, imaginative, and surprising than his earlier works. The works are not always easy to listen to, but they are always rewarding.

Written in 1887, seven years after his first Piano Quartet, the second one in G minor, Op. 45, was written without a commission, indicating that the composer simply wanted to explore that instrumentation further. He followed the format of his Germanic predecessors, Schubert and Brahms, by putting the slow movement in the third slot, right before the finale, instead of following the opening Allegro. But it’s that first movement, marked Allegro molto moderato, that establishes the importance of this work, both as a continuation of the Romantic tradition and as a challenge to the conventions of tonality (while never blatantly defying them).

The unnamed piano quartet relies on the rich, subtle playing of pianist Simon Zaoui. Violinist Pierre Fouchenneret, who is also in the string quartet, balances skillfully between passion and control. Zaoui also joins the complete Quatuor Strada for Fauré’s two piano quintets.

A pianist and organist himself, Fauré was never comfortable writing chamber music without piano. Thus, it wasn’t until the last year of his life, at the age of 79, that he finally tackled his one and only string quartet. By this point he was mostly deaf and, like Beethoven before him, responding as much to uncharted harmonies in his mind as to his musical training and experience. The plaintive Andante second movement is a good example.

Besides those compositions for four and five instruments, Fauré also created some for just two, some of which can be heard on the recent Works for Cello and Piano, released by the OnClassical label. Duo Simone Zaccaria is named after its two players: Gaetano Simone on cello and Maurizio Zaccaria on piano.

Fauré’s two sonatas for this instrumentation date from the last years of his life, meaning that they have his intensive late-period sound. To lighten the overall mood of the album, shorter, earlier works for cello and piano are interspersed between the sonatas, including Fauré’s own transcription of his song, “Après un rêve.” Another lovely example is the Romance in A Major, Op. 69, which Simone and Zaccaria play with elegance.

Still, the true stars of the program are the sonatas, full of tremendous, even severe emotions. The duo gives impassioned performances of both. Especially notable is the way each player’s individual sense of restless motion intertwines with the other’s. I did at times wish for more focus from Simone’s cello sound.

The composer’s hearing failed him starting with higher frequencies, so these works tend to feature the cello’s middle and lower registers, which only enhances their power. It took Fauré most of 1921 to write the Sonata No. 2 in G minor, Op. 117; he was delayed partway through by poor health. We should count ourselves fortunate that he managed to finish it.

Header image: portrait of Gabriel Fauré by John Singer Sargent. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Musée de la musique/public domain.