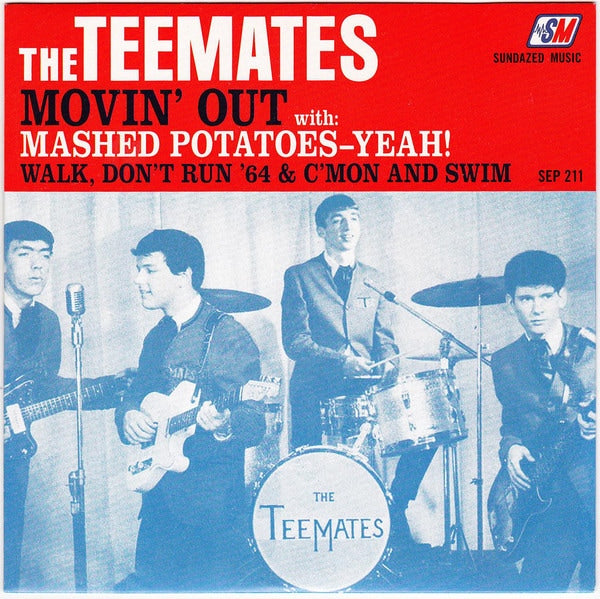

[We’ve previously written about the pioneering audiophile label Audio Fidelity on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the release of the first single-groove stereo record by the label, and in John Seetoo’s interview with Andrea Bass, daughter of founder Sid Frey. We’ve seen that AF released a wide range of content, from sound-effects and test records to recordings of bullfights and auto races, in addition to more mainstream music. After the advent of the British invasion, AF took a crack at the teen market with a NY rock band, The Teemates. John’s interview with singer /guitarist Bobby Pulhemus, who went by the stage name of Bobby Palomino, is both sad and fascinating as it describes the hard life and managerial manipulation of the band. Audio Fidelity doesn’t come into play much in this story, but it’s still a valuable portrayal of the music biz in the early ’60s—Ed.]

J.S.: What was your background growing up, and what led you to become a musician?

B.P.:I had a very disturbing upbringing, to say the least. Alcohol played a large part, as both original parents were heavy drinkers. Things got so bad that authorities awarded custody of myself and 2 sisters to my father. As the years went on, his drinking and violence increased. His work as a house painter became sporadic which soon led to the entire family relying on welfare as a means of income.

We wound up living in a two story, four room house which lacked heat, water, and sanitary facilities. Two pot belly stoves provided heat. We cut down trees from the nearby forest to use as fuel. Water was provided by a small cistern in the rear of the house which was gathered in buckets. An outhouse 25 feet away from the building was the toilet..

As I grew into a young adult, physical violence upon me and my siblings was not uncommon. School was 2 miles away and meant walking in the dark of winter. In summary, it was a classic “Tobacco Road”. We lived in Rockland County. It was very rural in those years, providing a summertime refuge in for city dwellers to retreat in the summer. School was a nonstarter for me. I started working at a Nyack luncheonette as a dishwasher after my sophomore year, leaving school permanently in the fall of 1958.

Dad had a stroke in 1959 which incapacitated him permanently. In 1962, my mother (I always addressed my step mother as Mom) was forced to move and relocated the family to Spring Valley, NY. We found ourselves a five room railroad flat and this would become the bedrock of my entrée into the music world.

Oddly enough-the very day my father suffered the stroke was also the day Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens died in that tragic Airplane crash.

It is a long story but it is that background history that became the foundation of my character today. Knowing hardship, and experiencing abuse from caretakers is the lowest rung of humanity, in my view. That is a major factor in why and how I consider myself a winner and a survivor when I entered the world of social interactions.

J.S.: Who were your influences as a guitar player in the 1960’s?

B.P.: American Bandstand brought my world into a new realm as Rock n’ Roll entered the world in the Mid Fifties. My mother was a big fan of country music, so it was those early country musicians who influenced me most. Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, Lefty Frizzell, amongst a few. Having secured a plastic Gene Autry Emenee Guitar my mother found in a thrift store, I taught myself to play in every spare moment I could find. My obsession was so intense that aside from eating, working dishwashing jobs was given over to learning the chords of all the oldies I heard, in addition to Johnny Cash and country music. Then came Chuck Berry, who became my greatest influence of all. The gift of music was a natural for me and to this day, I cannot read or write music. I never learned the true math of music creativity other than recognizing chords and being born with perfect pitch and rhythm. It would be my singular best ability to master rhythm patterns regardless of the math involved.

J.S.: How did you wind up forming the Teemates?

B.P.: I had worked in various local Rock n’ Roll bands over the course of a few years in my hometown of Spring Valley, NY. My first and favorite band was with my pa,l Sonny Belovich. Playing local teen clubs, the village park, and private parties, we had become quite popular. However I concluded that remaining with that band (The Sunliners) would take me nowhere. I hooked up with other bands, rehearsing in garages and basements of their parents’ homes.

One such band took us to enter a local Battle of the Bands contest. My band won the first contest but lost in the final face-off. Apparently, there was a person at the contest who liked the way I played guitar and the presence I carried onstage.

I, however, was still hurting from the loss, so I boarded a local Spring Valley to NYC bus. Arriving in Greenwich Village, I met others similar to myself. I remained there for about three weeks playing for tips in the various cafes and coffeehouses that were in abundance. Having emerged from a dank, dirty, poor past, I had always felt lesser than amongst not only my peers but people in general. These new musicians I was meeting shared the same through their prose and songs they wrote. As it got colder in late October of that year, I returned to Spring Valley. My mother gave me the phone number of the person who had called saying he wished to manage my talents

Joseph Shefsky had apparently attended the contests and had engaged a few other musicians whom he hoped could help him put a musical score together for a play he was writing. He was the one who had liked my stage presence and guitar playing. In early November, because I did not drive, he had one of the musicians, a drummer by name of Bryan Post, pick me up for a rehearsal at Joe’s home. Joe was young, very conservative looking, close cropped hair with gleaming blue eyes, who delivered dry cleaning from his parents’ cleaning store in Nyack, NY. He was married and had three small children.

We got right down to business. There would be no pay, so I would have to retrieve my former stock boy status at a local supermarket.

The lyrics Shefsky presented to us to put to music was, for me, almost a joke. I discussed this with Bryan on the way back and he agreed. The next rehearsal, Shefsky had brought in a kid from Waldwick, NJ who would become the group’s lead singer and bass guitarist. We rounded out the group by bringing in another guitarist whose dad had helped me purchase my Fender Jaguar guitar. Over the course of the month, slowly but surely, Joe’s interest in his songs grew dimmer as he began to realize the potential of the rock n’ roll songs the group played during breaks. We had even managed to put music behind some of the silly lyrics he gave us, which he was quite impressed with.

By the second week of December, Joe gave us a name. The T-mates. He would purchase band uniforms for us, which was merely a jacket with the name “T-mates” sewn onto the lapel. We all wore dark slacks, a white shirt, and slim, black ties. In late January, Joe announced we would be headed to the 1964 World Fair, which would be taking place that year in Queens, NY. Our venue would be the New York State Pavilion.

In February, The Beatles arrived in New York, and quite suddenly, all of our existing music ceased as we began learning and rehearsing these new Beatles songs. By spring, we had managed to perform almost to an exact copy many of the Beatles’ releases. In addition, we had all begun to allow our hair to grow longer with Joe’s approval. Soon, local neighborhood girls began gathering in the backyard looking through the glass sliding doors during our rehearsals. There were a few and those few became more.

Securing the name the T-mates became a legal issue. Without hesitation, Shefsky sought out legal advice and within a few weeks. the name, The Teemates was secured legally. The Teemates were born in late May, 1964.

The Teemates at the opening of A Hard Day’s Night.

J.S.:What were your gigs like and where did you play?

B.P.: In late spring of 1964, the Beatles released the Movie A Hard Day’s Night. By then, the Teemates name had become synonymous with the Beatles, evidenced by the huge crowds the group drew at various high school auditoriums, along with a few appearances in the New York area. Those shows included being on the same bill with groups like The Shangri-las, Freddie Cannon, and famed Deejays. Every appearance had the girls in the audience shrieking and screaming as we performed Beatlemania tunes like, ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and ‘And I Love Her” to name a few.

By the time the previews of the movie, A Hard Day’s Night hit Rockland County, who else but The Teemates, would be (chosen as) the band to perform a show in or outside the theater before the movie? The appearance at the World Fair cemented the Teemates into New York stardom, as the chaos that ensued during our gig was totally unplanned for. I had seen hordes of girls entering the venue as we set up, but little did I expect nearly one hundred of these young teenagers to rush the stage. Neither did Security. By the time we retreated to the dressing room, Richie’s shirt and jacket were nearly shredded, and there were major tears in both Gary Mercury’s and my jackets as well. Our physical appearance may not have represented the physical images of the Beatles themselves, but the stage presence we presented was straight out of the Beatles’ play book. I would be John. Shefsky determined after that show Mercury would not fit the picture he desired and was replaced by Robbie Lundius (RIP), a rip roaring hell of a lead guitar player well ahead of his time. It was he who not only helped boost the energy level at our appearances but gave (us) clear virtuoso guitar leads as well.

‘Moving Out’ was a song Joe wrote the lyrics for after the World’s Fair show. Because we ended our sets with ‘Shout’ (The Isley Brothers), he wanted an original of our own which could move the audiences to dance in the aisles. To just copy the chord changes of ‘Shout’ did not sit well by me. It was then that I created the run up the neck chord to reach the pitch and open the vocals.

That summer, we were the house band at Long Pond Inn. The venue also featured top name acts on weekends, many of whom we backed up musically, such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, and The Ronettes.

The top Deejays on New York radio also loved us. We played at Scott Muni’s (WNEW-FM DJ) east side Manhattan disco called The Rolling Stone, where many celebrities partied and where I got to meet Jeff Beck of the Yardbirds. The Teemates also would play at Cheetah, Trude Hellers, Peppermint Lounge and The Metropole Café, on Seventh Avenue off 48th Street, where acts such as Gene Krupa, Maynard Ferguson, The Dukes Of Dixieland, and Cozy Cole, to name a few, were the star acts.

Amazingly, we would become the first Rock n’ Roll band to perform on its famous stage set. But that did not mean we were the stars. What came with the territory would be 6 day matinees with Sunday both a Matinee and an evening stint. Weekends were long, gruesome, tiring and frankly; this was not my kind of fame at all.

[John Seetoo’s interview with Bobby Pulhemus will conclude in Copper #54—Ed.]

Cover of a Sundazed re-release of The Teemates’ singles originally released on Audio Fidelity.

Cover of a Sundazed re-release of The Teemates’ singles originally released on Audio Fidelity.

But I’ve only been to one show (“The White Album”) and have never had an interest in playing in one --- until this year. What got me out of the house?

But I’ve only been to one show (“The White Album”) and have never had an interest in playing in one --- until this year. What got me out of the house?

The Dream Syndicate with Claudia Lennear and Susan Cowsill, during soundcheck.

The Dream Syndicate with Claudia Lennear and Susan Cowsill, during soundcheck. Rob Laufer with Claudia Lennear.

Rob Laufer with Claudia Lennear. Backstage: Terry Reid, Elliot Easton of The Cars, Gary Myrick. Behind them is Don Randi, known for the Wrecking Crew.

Backstage: Terry Reid, Elliot Easton of The Cars, Gary Myrick. Behind them is Don Randi, known for the Wrecking Crew. Hey, hey, it's Micky Dolenz!

Hey, hey, it's Micky Dolenz! Andy Slater (l), former Capitol Records head, chats with Buffalo Springfield vet Richie Furay(r).

Andy Slater (l), former Capitol Records head, chats with Buffalo Springfield vet Richie Furay(r). Some of these folks you’ve heard of, some you haven’t. Some were good, some great, and all were sincere as hell.

When our turn came--- for me, having never played on the stage and trapped behind a low wall of amps, things weren’t all that great. I enjoyed the rehearsals more. Other than the drums, and despite our volume, things sounded swimmy and vague.

Some of these folks you’ve heard of, some you haven’t. Some were good, some great, and all were sincere as hell.

When our turn came--- for me, having never played on the stage and trapped behind a low wall of amps, things weren’t all that great. I enjoyed the rehearsals more. Other than the drums, and despite our volume, things sounded swimmy and vague.

Elliot Easton rocks out!

Elliot Easton rocks out! Syd Straw with Rob Laufer.

Syd Straw with Rob Laufer. Richie Furay with his daughter and band at rehearsal.

Richie Furay with his daughter and band at rehearsal.

These days, the Williamson's high levels of feedback has caused it to lose favor among valve aficianados---but for many years, it was king. It was so popular that Wireless World reprinted Williamson's articles in a booklet...this booklet:

These days, the Williamson's high levels of feedback has caused it to lose favor among valve aficianados---but for many years, it was king. It was so popular that Wireless World reprinted Williamson's articles in a booklet...this booklet:

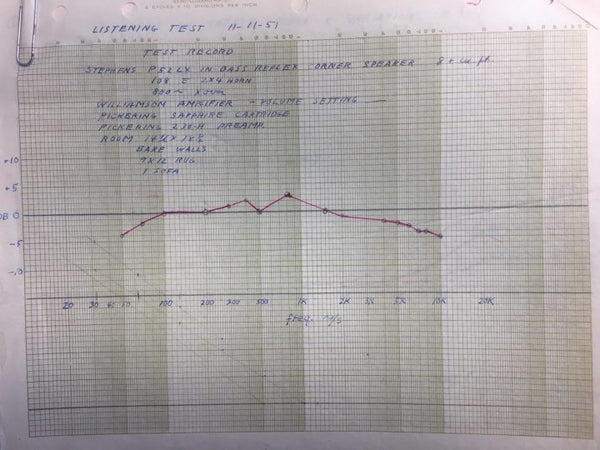

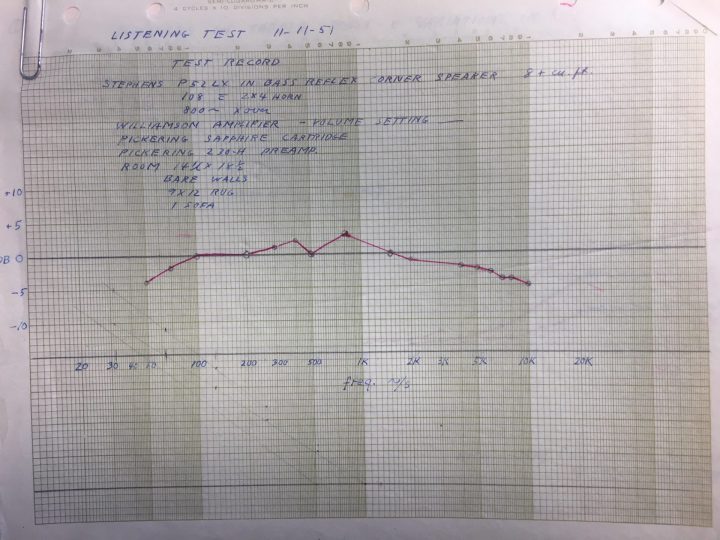

Similar graphs plotted the results of 1952 crossover experiments:

Similar graphs plotted the results of 1952 crossover experiments:  Even twenty years later, the Williamson amp was still in the picture, as component elements were checked to see if they were still in spec:

Even twenty years later, the Williamson amp was still in the picture, as component elements were checked to see if they were still in spec: