Steve Hoffman is one of the most highly-regarded mastering engineers in the recording industry, and his discography is a microcosm of 20th and 21st Century music history. The thousands of records to his credit span from the Great Depression era with Bing Crosby through World War II and the Eisenhower era of jazz, country and folk, Frank Sinatra, Buddy Holly, Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, The Doors, John Coltrane, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jethro Tull, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, all the way through to present day Metallica. Steve Hoffman has achieved such a rarefied status that he has garnered thousands of audiophile fan followers in a profession that few people outside of the recording industry technical side are even aware of. Steve spoke with John Seetoo for Copper, and shared some opinions and anecdotes from his home in Los Angeles.

JS: You aspired to be a musician, and recorded one semi-classic surf rock song, “Cecilia Ann”, with your band, The Surftones. Where did you go from there? Did you always intend to be involved in music?

SH: No, that Surftones thing – that was just a lark. We didn’t expect anything. It was something that happened only because of that Pixies’ thing; they heard it and wanted to record it for themselves. So when that happened, it was a happy accident. But basically, my career has always been behind the scenes. That’s where I’ve always wanted to be. I know I’m not a fantastic musician; I mean, I’m adequate, but nothing to make a career on.

So, I worked in radio broadcasting, and then I moved over to a record company, where I compiled albums on paper, you know, old stuff like Bing Crosby…and then I moved over to mastering of old recordings to make sure that they sounded nice.

JS: You also worked for poet and songwriter Rod McKuen back in the day. What was that like, and did that have any bearing on your future career? Was he a mentor, or are there any others in your career development that helped you to reach your current preeminence?

SH: Interesting question. I don’t consider Rod McKuen a mentor, he was basically just an assignment I had. The record company found him very hard to handle, so they sent me over there, because I’m amiable…and we just clicked right away; absolutely.

JS: Was this during your MCA days?

SH: No, no…after that. DCC Compact Classics. He wouldn’t answer the door for anybody because he was going through one of those periods where he didn’t feel like answering the door. So they sent me over there, ‘cause I was someone to whom he could relate since he was creative and moody and blah, blah…So, I got to know him and…we became real close. We spent a lot of hours together working on his back catalog, and…he was a really great guy, but as for mentoring me, no. I was already in it up to my neck at that point.

What we were trying to do was get his back catalog out on CD, and he didn’t quite understand what that entailed. We rebuilt this little in-house recording studio, and we remixed some of his old things and re-released them, and kind of brought him back out again into the spotlight.

JS: Were there any people that you would consider mentors; people whose revelations helped you to build on to get to your current level of status…?

SH: Yes, actually. You know, no one has ever asked me that, in all these years. That’s an interesting thing. There was a guy who not many people know now, but at one time he was pretty much a heavyweight in the industry, named Milt Gabler, and he was the guy who, in 1939, founded Commodore Records. When Billie Holliday wanted to record “Strange Fruit”, no record label would touch it, so his Commodore label put it out, and it went on to become famous. Later, he worked as an A&R guy for Decca Records and MCA. He did “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets, and many, many other great songs from that era. In his old age, I had him flown out to Los Angeles, and apparently no one at the record company had really talked to him for many years. I spent many days with him. And he got me all the contacts that made it possible for us to re-release Buddy Holly, Bill Haley…and everybody like that. So, he helped me out; he helped my credibility out. And I helped him to become remembered. You know, not only in the company, but outside the company as well, so he died a happy man.

JS: Wow, that’s great. It’s nice to be able to have a sense of giving back to the industry; to the people who made a difference in the history of recorded music. That’s wonderful. Did you intend to become a mastering engineer when you realized you weren’t destined to become a fulltime musician?

SH: No…I never wanted…I never even knew what a mastering engineer was. I wanted a job that actually paid money because I was still living at home with my parents. And up to a certain point, that’s ok, but after you get into your twenties, it’s like ok, you know, it’s time to get a real job now. So I worked in radio broadcasting. And when I moved over to the record industry, I was simply hired to do historical A&R, A&R, of course, meaning Artist & Repertoire. In other words, to utilize the back catalog of the record company (labels): ABC, Paramount, Dot, Decca, and Brunswick…all those songs that were lying dormant.

So I was working on a Bing Crosby record and writing down the songs that I wanted on it, and when I heard the test pressing that came back, one song from 1936 sounded wonderful, and then another song recorded at that same time had this echo on it, and it sounded horrible. I then made the decision, that constantly made me a lot of enemies, to find out what they used as their source material – why one song sounded great and a song recorded an hour later sounded horrible.

It turns out they were pulling the wrong versions of the songs, and the mastering engineers out there didn’t care. They would master whatever they were given. I put my nose in where it wasn’t wanted and started to learn what mastering was and how important it was. I kept hanging around, and finally, I was a part of it.

JS: Did you have any training as a cutting engineer or a recording engineer, or did you just hit the ground running as a mastering engineer?

SH: No. I knew how to engineer. I knew what compression was; I knew what dynamic range was from my several years in radio broadcasting. I did radio engineering in high school and in college at the big radio station here in town. They hired scab labor in those days because they were trying to break the engineering union, and I was about the most willing scab they could possibly find (laughs).

So, you, know, I got to learn how it was done. And I noticed, for example, if we had three versions of Paul McCartney’s Ram, and one sounded really good and another sounded really horrible, I would have to finally look at the leadout groove, and if the writing was not the same, I realized that whichever engineer worked on the bad sounding one didn’t do it right! So it whetted my curiosity.

Basically, I always worked in record cutting with another guy, Kevin Gray. He did the actual cutting part; I did the sound part. In other words, I made sure that it sounded the way I wanted it to sound, and he made sure he captured that sound on the actual record.

JS: You refer to yourself as a “music restoration specialist”. Is there any misunderstanding about mastering you’d like to clear up, and how you view your work as different from standard mastering? Do you have a particular philosophy as a mastering engineer?

SH: Oh yeah. Ok…you know, I’ve had the same philosophy, throughout my career and even before. If someone works very hard on a song, it’s the mastering engineer’s responsibility to do no damage. Unless it sounds really, really bad – then it’s the mastering engineer’s responsibility to make it sound as good as possible.

I always refer to mastering as, “hanging the Mona Lisa.” If the Louvre Museum loaned you the Mona Lisa so you could display it at a party, and you hung it in the living room and shined bright lights on it, you’re going to see all the cracks; you’re not going to be really thrilled with it. It’s how you light it, it’s how it’s hung, and how it looks – that’s what’s going to make the difference, and that’s what mastering is.

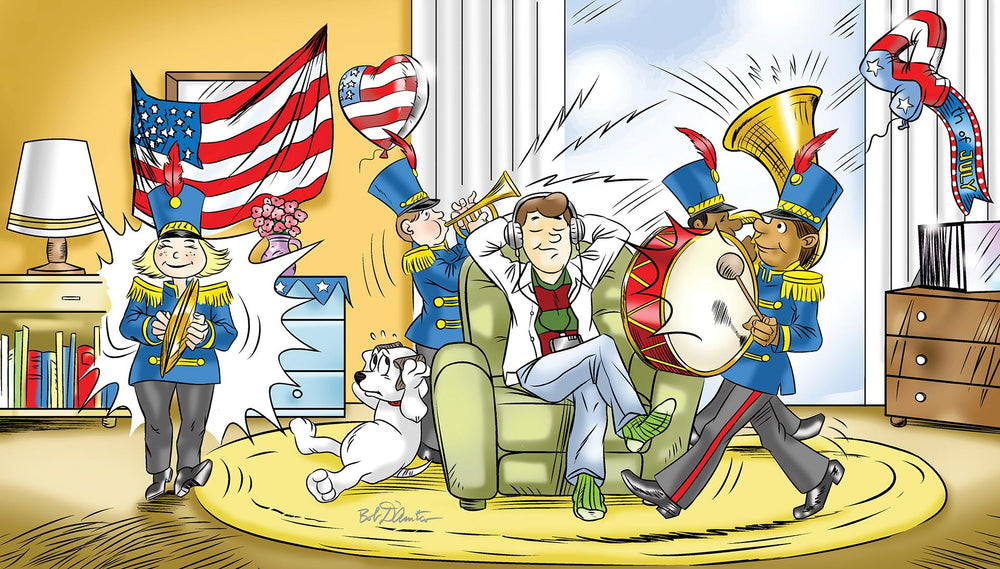

In my style of mastering, I want everyone to sound like they’re human beings, and I want to keep the dynamic range that’s on the master tape. Other than that – the mastering engineers, especially right now, the trend is to squash everything so that everything is loud, (even the quiet parts). And that is the absolute antithesis of my mastering philosophy.

J.S.: Were there any particular projects where you feel you “saw the light” and began to achieve and consistently deliver that higher standard of music restoration above that of the industry norm, since you say you didn’t work at all as an engineer in other recording capacities?

SH: Well, I hung around with those guys. I realized that end of the industry was not for me. I mean, working all day on a tambourine overdub on a song….I mean…ok, but I want to do something else. With mastering, half of the battle is finding the right source material. If you don’t have the right source material, you’re just wasting your time. Once you’ve spent hours hunting for the correct version of each song…but every single album I’ve done has been in the same way. There are projects where I’ve uncovered the actual master tapes that were never used, and I’d go, “Wow! That sounds really fantastic! Let’s make sure I don’t screw it up!”, but I never went, “Oh! This is the way to do it! Let me just ignore everything I’ve done previously, and concentrate on this style.” No, I’ve always had the same style. I’ve worked on thousands of albums: Buddy Holly, Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, The Doors, The Beach Boys, Frank Sinatra…and the list goes on and on. And you know, I’ve had that same sound in my head, ever since I was young, so that really hasn’t changed. It’s always been…almost the opposite of every other mastering engineer out there. (laughs)

JS: So you have an innate quality standard that you’ve always strived to achieve, and once you were in a position to do it, you just keep repeating that process and hitting that mark for yourself.

SH: That’s exactly right, John. That is perfect. I’ve got to copy that down to use that the next time someone asks me. That is absolutely it. You know, I’ve always heard it the same, and that’s never going to change.

J.S.: You’re associated with audiophile labels and re-releases. Is that by choice? Or would you like to work on new releases as well?

S.H.: No. I’m old and crotchety now, and I don’t like the engineering style of most of the new recordings out there; they’re absolute ear bleeders. You know, if you hear some of these bands live, they’re fantastic. But when you hear their final recordings, they just sound like – one note. And I try to explain to some of these guys, “Look, back off on all this signal processing and let the natural band sound shine through.” And they always say, “Yeah, but we don’t want to be quieter than anybody else on a CD or download. We have to be loud. ” Well, if you’re all loud all the time, you sound quiet. You know, unless you have something quieter to compare it to, it’s all annoying, and after a while, you lose interest, because your ears are just shutting off the sound. No, I like working with the old stuff. I’m happy with that.

J.S: Do you associate the heavy compression with the lower resolution quality of mp3 and streaming, or is it a style thing more than a tech thing?

S.H.: No. What happened is Sony, in their infinite wisdom, invented the CD changer. So now you had a tray with six CDs in there. One is really loud; one is naturally dynamic. So when you’re at a party, the naturally dynamic one comes on and nobody can hear it. So when the executives started realizing that, they told their mastering engineers to make everything sound loud, so you could hear it. And I can understand that philosophy, and that’s ok for something that was recorded in 1998, but you don’t – you don’t screw around with Bing Crosby! You make that loud all the time, you just make it sound – obnoxious.

J.S.: Agree totally. You’re primarily associated with projects released on CDs and SACDs. How does your job differ for vinyl or download releases?

S.H.: That’s another very good question. It doesn’t. It’s the same, every single time. When I am working on an LP, all we have to worry about is that the record doesn’t get too loud so that it’ll break the groove or that it gets too quiet and goes under the noise floor of the actual surface of the record. Other than that, I do not change my style for CDs or for SACDs or any other platform. It always sounds like me. You know, a lot of people love that and a lot of people don’t like it. So, I don’t change my style.

J.S.: Do you still see strong demand for physical media like CDs?

S.H.: I do. But I’m in a world of audiophiles, and they want to hold it in their hand. You know, they want numbered editions, they want something tangible; they want something saying that there’s artwork. They’re not really into downloads, although that may change when the next generation comes in. That wouldn’t surprise me. For now, no, it’s always an SACD, vinyl or a CD.

JS: Are they any particular types of projects you prefer to work on, or particular types that you refuse to accept?

S.H.: I like Asian rap – that’s a joke. (laughs) No, I don’t care what it is. You know what? I fall in love with all my projects. And even if it’s something that I don’t like, I find something about it to love. That’s the only way I can actually operate.

J.S.: There’s actually some Asian rap you’d probably have fun with, because there are some that use gamelan and traditional Asian and Southeast Asian instruments which can have some very interesting dynamics.

S.H.: I know. And a lot of it is actually extremely well recorded. I mean, unbelievably well recorded. Yeah, I like pretty much everything. I was brought up in that old school: you listened to some classical, you listened to some jazz, you listened to pop, you listened to world music, you listened to everything – it’s all good. You listen to Buddy Holly and to Miles Davis, and you find something to love about both.

So that’s me. And fortunately, it turned out really good for me and my career that I am like that, because I’ve worked on the most eclectic amount of crazy albums from all eras, and I love it all, so I’m happy.

[We’ll conclude John Seetoo’s interview with Steve Hoffman in Copper #37. In Part 2, Steve discusses his well-known Forums, why razor blades are important to his work, and his favorite projects. Thanks to Steve and John for a great interview! —Ed.]