Historical performances don’t get a lot of love from audiophiles. And let’s face it: many historical performances were recorded using primitive equipment, under less-than-ideal conditions. To modern ears, accustomed to the latest, state-of-the-art recording technologies, many of these older performances can be painful to listen to.

But during the first half of the 20th century, some of the greatest classical musicians who ever lived gave performances that remain, today, the subject of legend. I’m thinking of artists like Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Bruno Walter, Felix Weingartner, Alfred Cortot, Ginette Neveu, Jascha Heifetz and many others who are still worshipped as the greatest exemplars of their art.

Contemporary critics wrote of the unique sound that these artists produced. But alas, their “golden” years took place long before the advent of modern recording technology, and today’s audiophiles can only guess at the sounds that they’ve missed. Even artists such as Otto Klemperer and Maria Callas who did make recordings during the stereo era nevertheless did their best work years earlier, at least if we are to believe those who heard them during both periods.

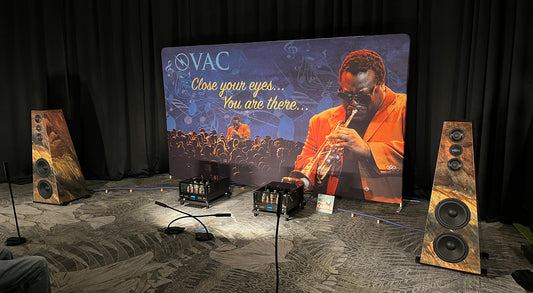

Today, we can only dream about the experience of sitting in the audience at La Scala as Furtwängler conducted Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen with Kirsten Flagstad. Or only imagine the electricity in the air as Toscanini leads the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Beethoven’s Ninth at Carnegie Hall.

Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting Das Rheingold.

But in recent years, a dedicated cadre of committed recording engineers have worked tirelessly to make those remarkable sounds more accessible to modern ears. I’m thinking about engineers like Mark Obert-Thorn, Ward Marston, Peter Harrison, the team at Immortal Performances, and – the focus of this article – Andrew Rose at Pristine Classical.

Andrew was a senior sound engineer at the BBC and an innovator in the field of sound restoration. In 2004, he picked up and moved to a small village in France, where he has committed himself to bringing great historical performances to modern ears. His technical skills were also instrumental in uncovering the Joyce Hatto fraud. (A quick Google search will provide loads of information about that scandal.)

But I digress. What Andrew and his team have accomplished is nothing less than bringing back to life some of the greatest performances of the past 100-plus years in greatly improved sound quality. In 2007, Andrew developed a technique called XR Remastering, which he continues to develop and improve. Here’s what Pristine’s website says about XR Remastering:

“It starts with what has been termed elsewhere [as] “tonal balancing.” Most of the microphones used to make historic recordings (and even more so the horns used in acoustic recordings) had very uneven frequency responses. We use advanced computer analysis of the tonal content of these recordings to “reverse engineer” and counter the impact of those tonal distortions. This results in a much more natural and realistic-sounding recording, limited only by the other constraints of the original source (frequency range, noise levels etc.).

But this is just the beginning. We were the first to release recordings where wow and flutter – the inconsistencies of pitch common to all analogue playback systems, but particularly prevalent in older recordings – had been fixed using a groundbreaking German computer solution called Capstan. Its [expensive] pricing means we remain one of the few companies working in this field to use it and its impact, particularly [on] piano music, can be immense.

Another innovation has been the use of a technique called convolution reverberation. A large number of older recordings were made in especially “dry” acoustics to combat the noisy, low-quality reproduction systems of the time. Yet we hear music in concert halls specially designed for acoustics that complement and enhance the sound of the musicians playing there. Convolution (a complex mathematical procedure) allows us to effectively “place” our recordings in some of the finest acoustic spaces in the world – renowned concert halls, opera houses, churches and cathedrals. When sensitively and delicately applied, this can add an extra dimension and sense of sonic reality to even the oldest recordings. It’s a far cry from using echo or digital reverberation to try and hide problems in recordings!”

As a listener, the results are astonishing. Familiar recordings suddenly sound completely different. Take, for example, Toscanini’s recording of Puccini’s La Bohème (Pristine PACO110). The original 1946 RCA recording is somewhat dim, with attenuated low frequencies. But in Pristine’s remastering, with the addition of an effect they call Ambient Stereo, it sounds like it was done at least 10 years later. There is a real sense of space and the instrumental colors are allowed to shine through.

Arturo Toscanini conducting La Bohème.

Earlier, I mentioned Furtwängler conducting the Ring at La Scala (in 1950). Those performances starred some of the greatest singers of the postwar period, including the iconic Kirsten Flagstad, in thrilling voice. And they were recorded and eventually released on vinyl on a Murray Hill box set, albeit in execrable sound. But what Pristine has accomplished with this set is nothing short of a miracle (Pristine PABX002).

If Furtwängler is not your taste but you still crave Wagner, you can choose from restored Ring Cycles from Clemens Krauss (Bayreuth 1953, Pristine PABX004) or Erich Leinsdorf (Metropolitan Opera 1961/62, Pristine PABX022). For that matter, there’s also Furtwängler’s later Ring cycle from 1953 with the RAI (Pristine PABX003).

If Wagner is not your particular cup of tea, there are still endless other treasures to explore. How about the legendary 1953 recording of Puccini’s Tosca with Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano and Victor de Sabata (PACO080) in hugely improved sound? Or, if your tastes run more to orchestral music, Pristine has done a remarkable job with Otto Klemperer’s legendary Beethoven symphony cycle (PABX012). Recorded in early stereo, Pristine’s remastering makes it sound like it was recorded yesterday. The same loving care was extended to Klemperer’s Brahms cycle (PABX027).

Otto Klemperer conducting Beethoven.

Other great artists who are represented on Pristine include Sergei Rachmaninov playing his own compositions, Leopold Stokowski, Guido Cantelli – Toscanini’s protégé who died tragically young – Lily Pons, Lotte Lehmann, Willem Mengelberg, Karl Muck, and a literal alphabet of the greats of the early 20th century.

If your tastes run to jazz, you’ll find wonderful early recordings by Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Charlie Parker, Art Tatum, and others.

Whether your listening predilections lean toward chamber music, solo voice, instrumental music, concerti, symphonic music, or opera, Pristine has offerings that will intrigue and delight you. I invite you to explore and enjoy.

We spoke with Andrew Rose about a variety of topics, enough for a two-part interview. The first segment appears here, and the conclusion will follow in Issue 163.

Ted Shafran: First and foremost, thank you very much for taking your time to do this with me.

Andrew Rose: You’re most welcome.

TS: The reason I proposed this article to Copper is because I admire very much the work you’ve been doing. So, let’s start with a bit of background. You were a studio manager at the BBC?

AR: That’s correct. I did a very unusual music degree at the time – a Bachelor of Science in Music at City, University of London and went directly from there to BBC Radio as a studio manager.

TS: What did your job at the BBC entail?

AR: It was primarily working as a sound engineer on national and, at times, international radio. I worked across a lot of different disciplines: everything from editing tape to mixing complex new shows to sound-balancing different recordings to going out and about recording stuff, and mixing and editing pieces and packages. Basically, anything that was required for the broadcast, so I’ve worked in a variety of radio programs. I joined in 1990 and left in 2004. I did some music programs, I worked in the political section for six years. The crucial thing to say, really: I was there at the time where radio and sound recording and editing and mixing moved from the analog to the digital sphere. I was involved with a show on BBC Radio 4, which is the national [spoken-word] network, which was the first to be edited and mixed and produced entirely on desktop PCs, starting in 1998. So, I was kind of working there on the kind of technical stuff that has enabled me to do what I’m doing here today. Prior to that, everything was reel-to-reel tapes and razor blades and the traditional way of cutting and mixing and editing. I just happened to be there at the right time to catch the waves of the internet and digital recording, and on that wave of new technology that came in while I was there.

Andrew Rose (with record) with BBC Radio Three presenter Andrew McGregor. Courtesy of Andrew Rose.

TS: What was the reason you decided to leave?

AR: [My family] emigrated to France for various personal reasons. I had already set up Pristine in the UK in my spare time as a sideline business, working mainly on private transfers for people digitizing recordings off different media, including reel-to-reel tapes and 8-track cartridges and all kinds of stuff. Generally, personal recordings, but also some commercial recordings that I was doing before we left. I had reduced my hours at the BBC and we had a viable business and we brought it with us here to France. And one of the things that I had planned to do while were here was to do the kind of work I’m doing today, albeit I didn’t envisage [ultimately] setting up my own record company.

I had contact with a couple of large record companies in the UK and things were looking promising. I had acquired a big collection of 78 RPM discs that I was transferring, and putting together potential releases, but of course, 2004 was not a good time for the music business. I did end up doing a few releases for a small record label, but the kind of thing that we were hoping to get – I won’t name the company involved but basically one of the larger independent classical music companies – we were on the brink of doing a deal with them when they had to pull the plug on that, and [on] a lot of their own business, just because finances were getting squeezed at that time. I was looking at the internet and thinking, “Hmm, this is possibly the solution to the problems that people have got at the moment.” And I figured that as soon as we could figure out a way to construct a website that I could manage myself, if only to set up a shop window for my work, I could have some kind of online store selling a few downloads of historic recordings that I had remastered. So that’s where it all began.

TS: It sounds like Pristine started as a side business. But I’m curious what your business volume looks like these days. For example, how many downloads are you selling in a month?

AR: That is a very, very good question, but it isn’t actually easy to calculate. Let me go back to the launch of Pristine, which was February 2005.We had only a few downloads available and it took five weeks to sell our first download. We were very lucky at the time. The editor of Gramophone Magazine at time, James Jolly, figured that this might be the way things would go, and he decided, a couple of months after we launched, to begin a downloads column in Gramophone – they needed something to write about. At the time there was ourselves, iTunes, and Chandos, nothing else at all. So Pristine, as a tiny little two-page website, got equal billing to Apple and iTunes for several months. But we were selling very, very, very small quantities. The business started to grow, I guess by 2008/9/10. I was winding up the other side of [my career at the time], telling my private customers that I’m sorry, I’m just too busy and really need to concentrate purely on the Pristine Classical business.

So that was probably maybe 12 – 13 years ago that this became our total source of income. We came over with enough money to get started, but we needed a business that would be able to sustain us and it took maybe four or five years before that was the case. What’s interesting is that maybe just over 55 percent of our income is from downloads, but still maybe 40 – 45 percent is [from] CDs. So, it’s not all downloads. It started that way, but we had so many people asking for CDs that we quickly realized that mail order CDs was a market that we had to pursue.

TS: Interesting. And that begs a question. Since a large chunk of your sales are CD-based and since some of your downloads are 24-bit, have you thought about doing SACDs?

AR: No. To be brutally honest, we’ve been waiting and waiting for CD sales to drop off. It’s increasingly a difficult thing to manage. We make CDs to order. We’ve got about 1,100 different products and some of those will be a single CD, while some will be double, triple, or quadruple sets. With a catalog that big, we can’t keep stock – it’s just not financially viable. Some of these releases won’t sell for months or years, and then one order will come in. And it has been the downfall of other record companies; producing a certain number of discs of any particular release and then leaving them in the warehouse for years because they’re not selling. The other problem is that since COVID, the cost of shipping has gone through the roof. So, from our perspective, anything that moves people away from hard, physical media towards downloads or streaming is something the we would welcome. I’m not entirely sure what kind of market there would be for SACDs. We offer 24-bit downloads because people kept asking for it. I actually work in a 32-bit media when I’m remastering. It retains the quality, but I don’t really see a benefit to 24-bit with historic recordings.

TS: One more business question before we talk about music. I know that some of your recordings have been restored by people like Ward Marston and Mark Obert-Thorn, but do you have any other staff beyond that, or is it basically all you?

AR: I started out with a guy from England called Peter Harrison, who unfortunately died about eight years ago. He was producing a third of what we released while I was producing the other two-thirds. About 2007 or 2008 I decided it would be nice to widen this a little bit and I got in touch with Mark, and then with Ward, and it’s worked well with Mark. I’ve got the volume of work that I like so I’ve never really looked for anyone else. Mark puts together [short- and long-term] projects, and that works nicely. It gives me enough work to keep myself busy and enough time to keep on top of the business and have some time for myself.

I have had other people inquire [about doing work for Pristine] and frankly I’m not particularly keen on what they have to offer, [or] on how much they wanted to charge me. Mark and I have had a really good working relationship. I have actually met him [only] once on my only visit to New York. He drove up from Philadelphia and we had lunch together. We get on really well. And I encourage him to do his own pet projects, [and] to not worry too much about the commercial viability of what he does, although it’s nice when they do sell in any significant numbers. We get the collectors coming in for his output whereas mine is more often the more mainstream – the stuff that actually sells, usually not the rarities. For example, one of his current projects is the [conductor Fabien] Sevitsky recordings with the Indianapolis Symphony [Orchestra], which have been originating from Sevitsky’s nephew. I think we’re currently up to Volume Six. I would never have heard of Sevitsky, let alone known where to look for the recordings.

Word travels slowly but [news about our recordings] gets picked up in various reviews, which bring people to our website. I wouldn’t say any of it sells in vast quantities. If I put out a Maria Callas recording that everyone’s already got three or four [versions of], I’m [still] going to sell a lot more of that than I would a Sevitsky recording. But that’s the kind of thing that I really welcome from Mark – these kinds of projects that bring in some of the more obscure performers. And Mark’s approach is different from mine and that’s interesting.

TS: Yes, I noticed that, for example, he doesn’t use Ambient Stereo.

AR: No, and there was a time where, if he was working on a project from vinyl rather than shellac, he would send it to me and I would “Ambient Stereoize” it, because people were asking for it. But then I decided that he should produce his own finished product in the way that he prefers. I would say that I’m definitely more interventionist. Ultimately, we come at similar problems from different angles.

This interview will conclude in Part Two in Issue 163.

About the Author:

Ted Shafran is the president of Connectability.com, a Toronto, Canada-based IT solutions company. He has studied piano, music theory, and voice, and sings with the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, the oldest arts organization in Canada. He is also a long-time record collector and audiophile.

Header image courtesy of Andrew Rose.